9.3: Water - The Fuel for the Medieval Industrial Revolution

- Page ID

- 212667

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Despite the greatest industrial complex of the Roman Empire being the imperial grain mill at Barbegal near Arles in what is now southern France (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)), and the knowledge of gearing used for the mill, the waterwheel (the power source of the Barbegal’s power) was little used in the ancient world. This was probably due to the high slave population obviating the need for labor saving devices. However, it may also be that because the Roman Empire was very centralized, they could provide flour on a large scale from a few highly mechanized locations. Upon the fall of the Roman Empire, the knowledge of water power would have been lost were it not for the writing departments of churches and monasteries that continued to operate through the subsequent Dark Ages.

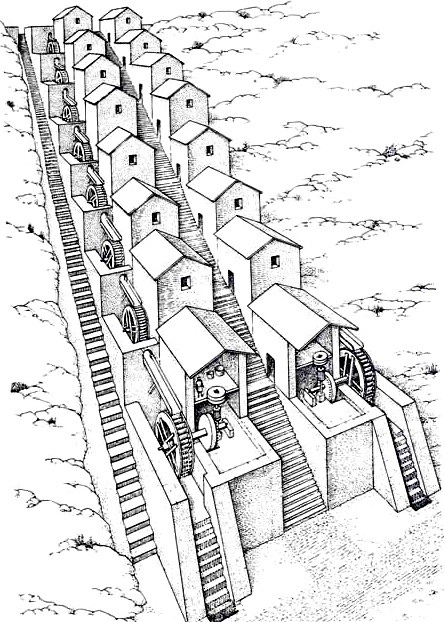

The Barbegal mill is probably the first example of industrial mass production. It consisted of eight pairs of waterwheels positioned on a 65-foot slope (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The wheels were turned by water that fell from a reservoir, which in turn was fed by a magnificent aqueduct. The sixteen wheels each powered two grindstones using a set of gear that allowed the horizontal shaft from the wheel to turn a vertical shaft on which the grindstones were positioned. Grain for the mill was imported from as far as Egypt, and the flour production was eight times than that required for the local population of 10,000, resulting in an export business. Unfortunately, upon the fall of Rome the technology of waterpower almost ceased since the small city-states set up had no need for industrial complexes.

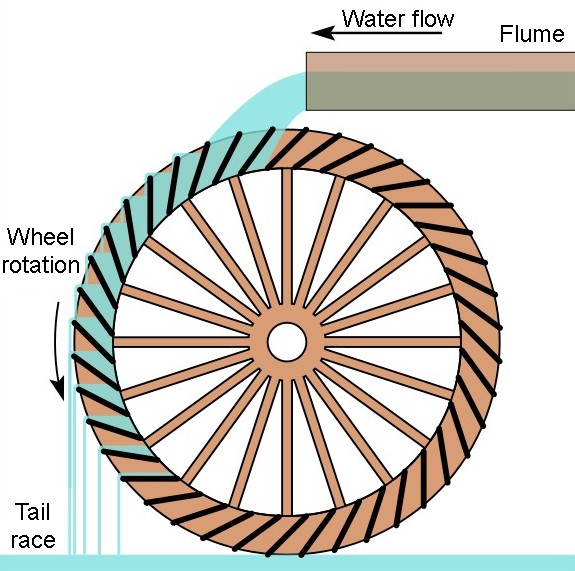

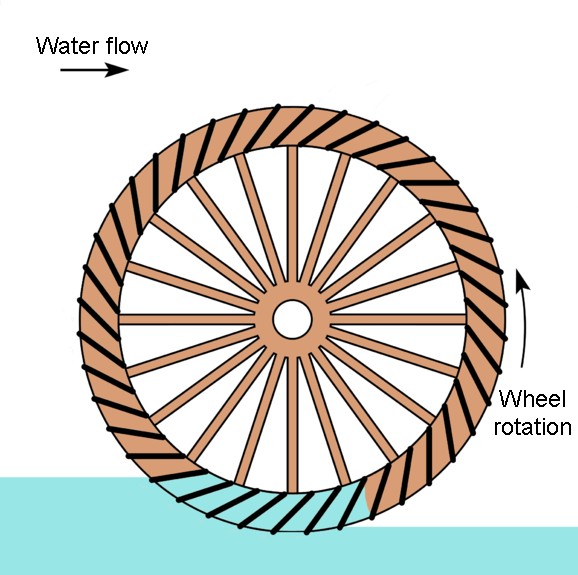

There are two general designs of waterwheel. The first is powered by water falling from above the wheel and is called an overshot wheel (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The alternative design, the undershot wheel, relied on water flowing on a river or pond such that the current moved the paddles at the bottom of the wheel (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)).

Despite its fall from use, the waterwheel was not forgotten. Due to the writings of 14th century BC engineers, such as Vitruvius (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)), whose texts had been preserved in the libraries in churches and monasteries across Europe, the waterwheel powered mills made a resurgence between the fifth and the tenth century. In most cases mills were owned by the church, since they had the knowledge (from ancient texts) to construct the mills and, possibly just as important, the literacy to develop the accounting system for their profitable use. The church would lease mills to farmers on a time usage, and they would take payment in flour. The owners of waterwheels and their mills were the first barons of industry post the Dark Ages. In fact, the fact that the Saxon word for an aristocrat is Lord, which means loaf giver, suggests the importance of the waterwheel. By the end of the tenth century the waterwheel was in widespread use across Europe. The Domesday Book (the nationwide census carried out by the Normans after the invasion of England) listed nearly six thousand grain mills in 1089.

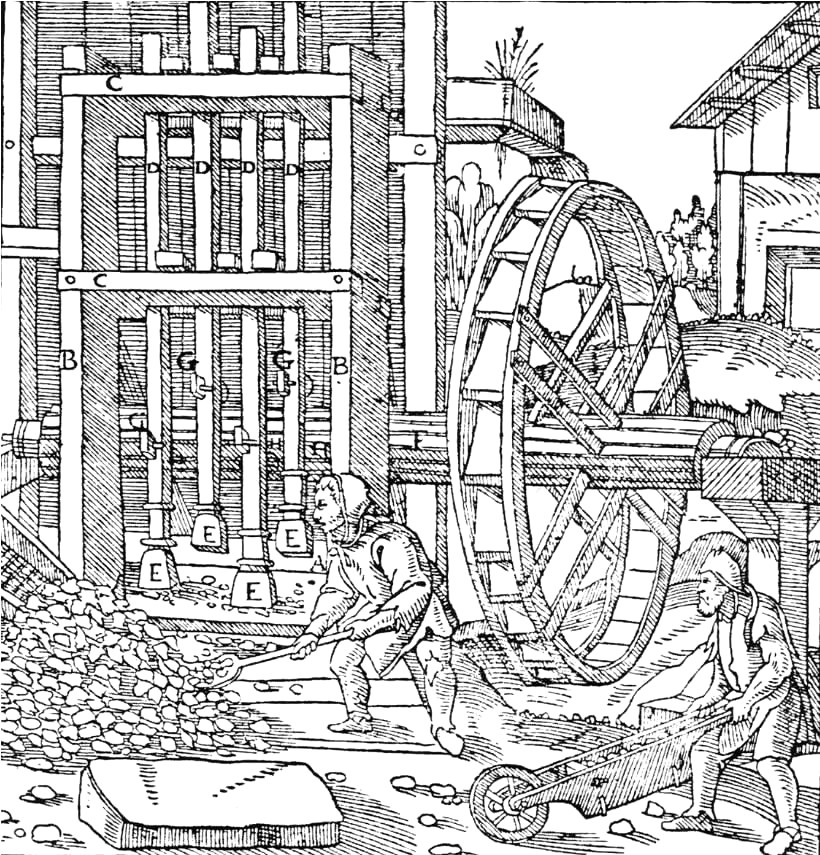

Despite the large number of waterwheels, the gearing used up until the ninth century was little different to that described by Vitruvius and used at Barbegal. Then around 890 AD the monastery of St Gall a new device was attached to the waterwheel. Instead of gearing to transfer power from horizontal to vertical rotation, a piece of wood was set into the shaft driven by the waterwheel (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). What had been created was a cam, since as the shaft turns the protruding piece of wood its anything in its way. For example, the first recorded use, by the monks at St Gall, was to crush malt for beer. However, the cam could be made to trip a hammer with every rotation (pounding), or to act on a crank to turn a rotary motion into a horizontal back-and-forward motion (cutting), or to push down a level and activate a suction pump (raising water from a well), or operate a bellows (for a metal forge). The range of motions meant that waterpower could now be used for a wide range of industries. By the end of the tenth century there were waterwheels powering forge hammers, oil and silk mills, sugar cane crusher, tanning mills pounding leather, grinding stones, ore crushing mills (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)), and as fulling mills for the rapidly expanding trans-European textile industry.

As a consequence of the waterwheel and the cam, the period between the tenth and fourteenth centuries has come to be known as the Medieval Industrial Revolution. It is interesting to note that water played a key role in the driving force during the next Industrial Revolution four hundred years later – the steam engine.