7.2: Carbon Black- From Copying to Communication

- Page ID

- 212652

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)It is a commonly held fallacy that James Watt (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) was the inventor of the steam engine. This actually honor belongs to Thomas Newcomen (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Watt’s actual achievement was to improve Newcomen’s design of a steam pump. While Watt was working in the repair shop at the University of Glasgow he was fixing a Newcomen pump when he developed several key improvements on the original design.

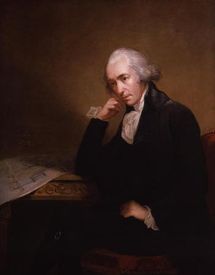

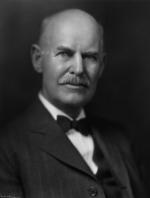

The reason for Watt’s success was that Britain was going through a major industrial boom and was in need of significant quantities of raw material including coal. Many of the coalmines, especially those in Devon were prone to flooding. Unfortunately, Newcomen’s engine (which was actually a steam pump) could not pump the water out fast enough, whereas Watt’s engine was powerful enough to drain the mines. As a result Watt’s career as a manufacturer was assured. However, Watt did not see the full potential of his invention, this was left to an employee of his, William Murdock (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), whose invention of the gearing to allow the steam engine to be used for powering machinery.

One outcome that Watt found from his increased business was an increase in paperwork! While he was living in Redruth, Cornwall, close to where many of the mines were situated he told a friend that he was having “excessive difficulty in finding intelligent managing clerks”. In 1780 Watt solved his paperwork problems by inventing the first method of making copies. This was the subject of a Patent entitled “A new method of copying letters and writing expeditiously”. Watt’s invention involved making ink out of gum Arabic and carbon black.

Note

Gum arabic, also known as gum acacia, is a natural gum made of the hardened sap taken from two species of the acacia tree; acacia senegal and acacia seyal. Carbon black is a form of amorphous carbon that has a high surface area to volume ratio it is commonly produced by the incomplete combustion of heavy petroleum products such as coal tar.

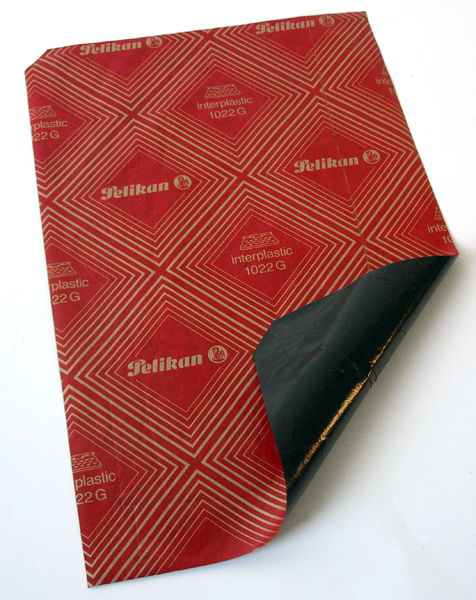

Watt’s ink would stay wet for 24 hours. Writing with the ink and then pressing the result against another piece of paper created a copy. Initially there was great resistance to the copy paper. In particular banks believed that this form of copying could result in forgeries. However, by the end of its first year on sale, Watt sold over 200 examples. The real commercial push came after Watt demonstrated his process to the House of Parliament. The resultant consternation amongst the Members of Parliament resulted in their having to be reminded that Parliament was still in session! By 1785 copies were in general use, however, Cyrus P. Dalkin made the biggest advance in 1823. By using a mixture of carbon black and hot paraffin wax the back of a piece of paper was coated. The carbon black was transferred to another piece of paper underneath by the pressure of the pen. Dalkin had created carbon copies. Both Ralph Wedgwood in England and Pellegrino Turri in Italy had developed forms of carbon paper between 1806 and 1808, but it was Dalkin’s version of carbon copy paper that found usage.

Initially there was almost no market for this new carbon copy paper, until in 1868 when American Lebbeus Rogers was talking part in a balloon ascent. Rogers was an owner of biscuit and greengrocer companies, and was intrigued when a reporter for the Associated Press who was interviewing him used Dalkin’s carbon paper. Rogers gave up his biscuit business and founded a firm to sell carbon paper. In 1873 he talked with E. Remington and Sons the typewriter manufacturer, and it was this application that created a success out of the carbon paper business.

Note

The term “CC” commonly used in e-mail programs today grew from the use of carbon paper and means carbon copy.

Interestingly, carbon black is still used today in modern photocopiers and laser printers. One of the attributes that allow its use is the ability for carbon black particles to become charged. This is related to another application of carbon black in early communications: its ability to conduct electric, and the changes that occur as a function of external pressure.

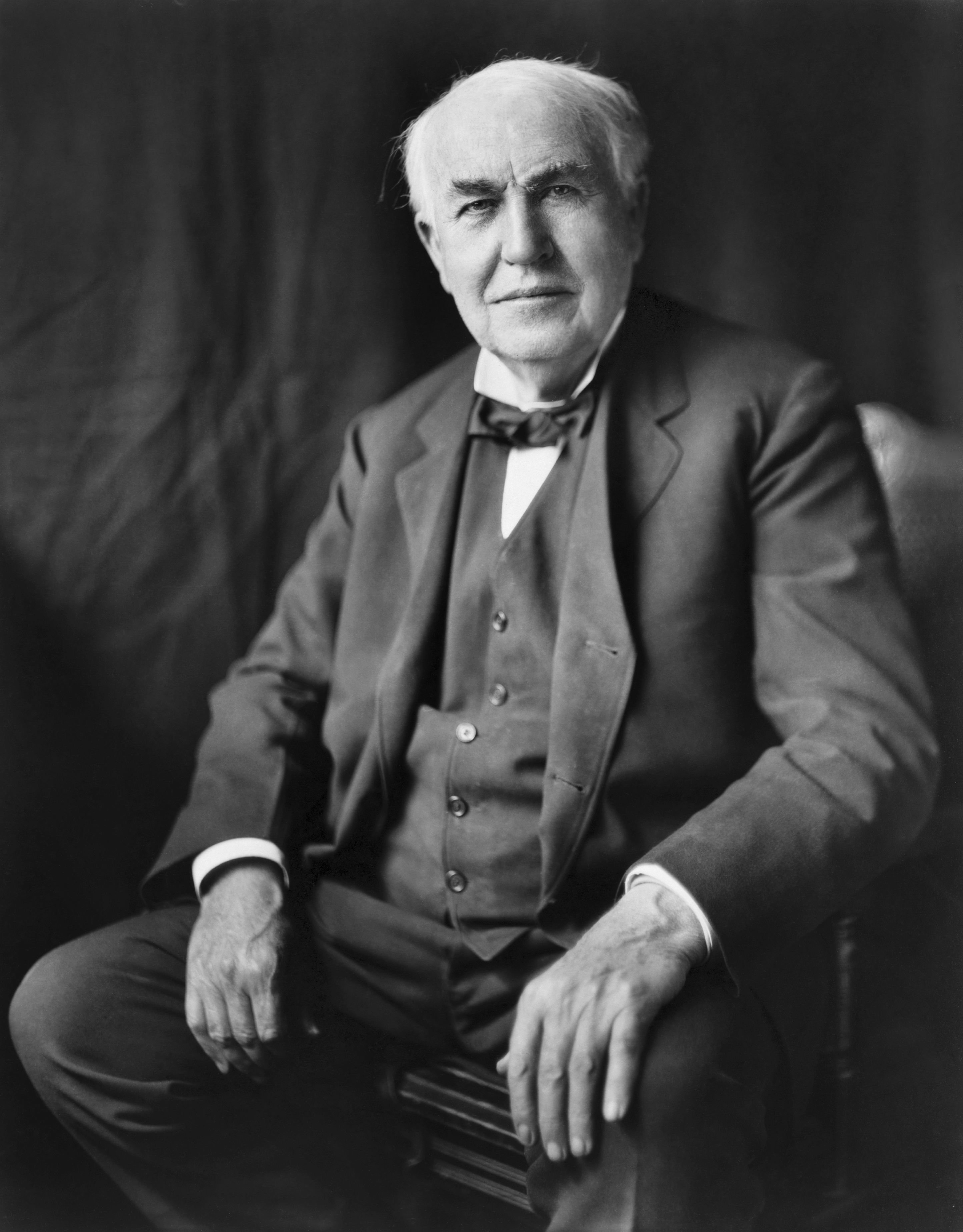

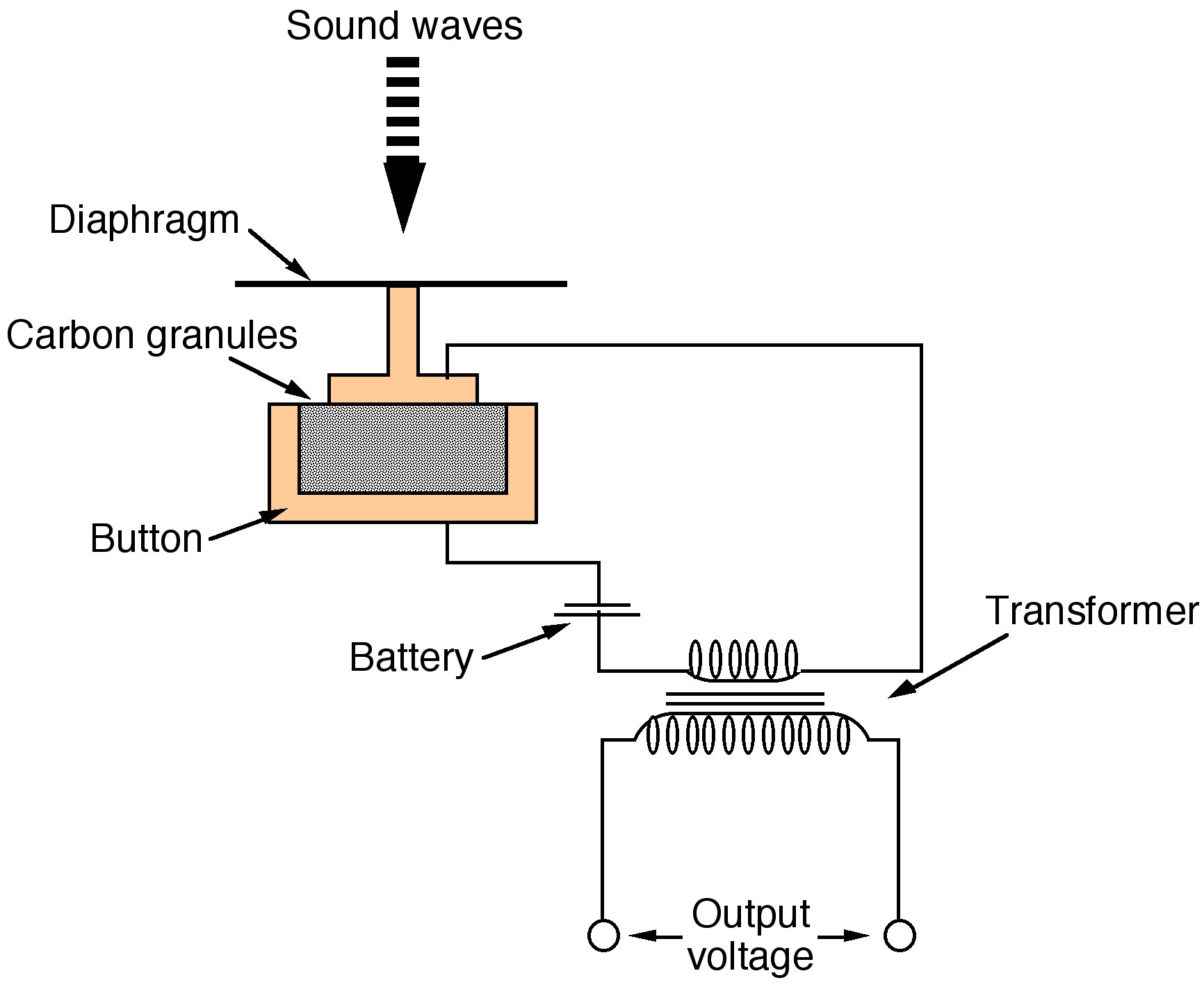

While Alexander Graham Bell was the first to be awarded a US patent for the electric telephone in March 1876, it was an invention by Thomas Edison (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)) that provided significant improvements. Early telephones relied on a metal diaphragm that was attached to an electromagnet. Speaking into the metal diaphragm caused its vibration, which in tern vibrated the electromagnetic and hence created a current. Unfortunately, the current was very low and subsequent clarity was poor. Between 1877 and 1878 Edison investigated methods to improve the clarity of the signal. The key development was the carbon microphone (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)).

The carbon microphone, also known as a carbon button microphone consisting of two metal plates separated by granules of carbon. One plate faces outward and acts as a diaphragm. When sound waves strike this plate, the pressure on the granules changes, which in turn changes the electrical resistance between the plates. A direct current is passed from one plate to the other, and the changing resistance results in a changing current, which can be passed through a telephone system. The carbon microphone was used in all telephones until the 1980s.

It was one of Edison’s researchers, Edward Acheson (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)) whose discovery allowed for the extension of communication on a global scale. While trying to make artificial diamonds, Acheson began mixing clay and coke (carbon) at very high temperatures. In an electric furnace at high temperatures he found hexagonal crystals of silicon carbide (SiC) attached to the carbon electrode. He called this material carborundum. When, by mistake, he overheated the mixture to 4150 °C he found that the silicon evaporated (boiling point 3265 °C) leaving pure and highly crystalline carbon: graphite.

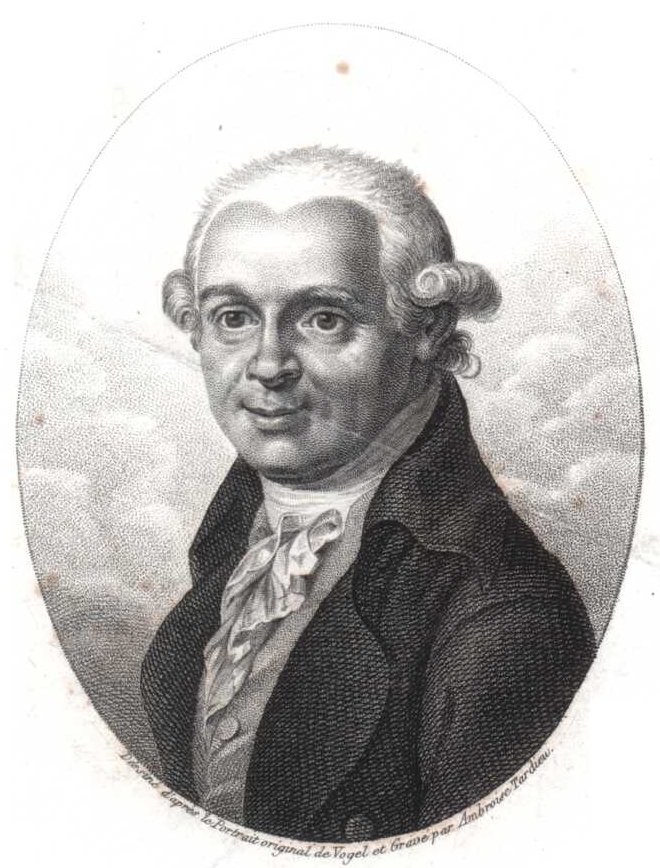

Graphite is a natural mineral normally associated with other minerals, although an enormous deposit of graphite was discovered in Cumbria, England, which the locals found very useful for marking sheep! Graphite was named by Abraham Werner (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)) in 1789 from the Greek graphein meaning to draw/write due to its use in pencils. However, its use was limited due to the cost. The ability to manufacture high purity graphite resulted in its use in electrodes, dynamo brushes, and batteries. The most terrifying application of graphite was as a result of a material problem associated with the V-2 rocket built by Germany during the Second World War.

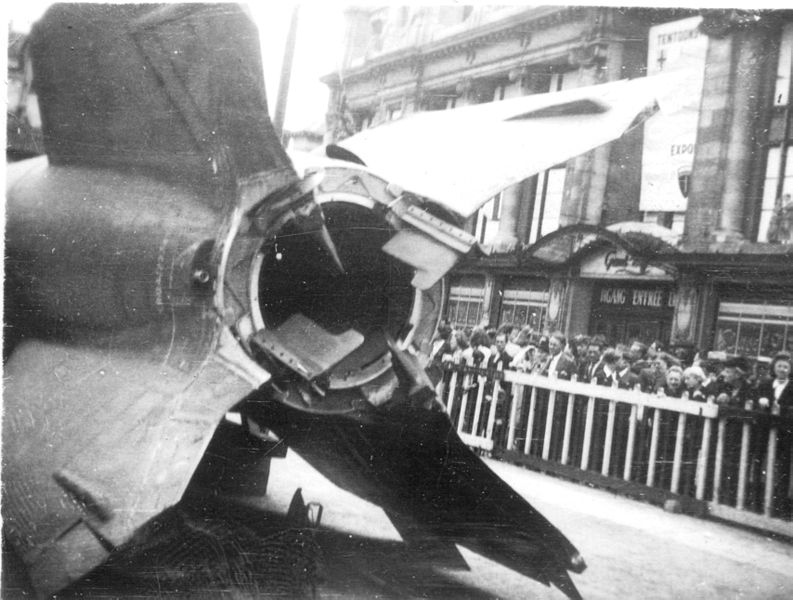

The V-2 rockets or Vergeltungswaffen-2 (vengeance weapon-2) was 47 feet long, and reached 3,600 mph with an altitude of 300,000 feet (Figure \(\PageIndex{9}\)). In order to control the direction of flight the V-2 was guided by four external rudders on the tail fins, and four internal vanes at the exit of the jet (Figure \(\PageIndex{10}\)). These vanes were made of graphite, it being the only material that would survive the extreme temperatures.

Of course it was as a result of the same German scientists who worked on the V-2, working for NASA, that allowed rockets of sufficient power to escape the Earth’s gravitational pull and send man to the moon, and position many of the satellites that are now vital for global communication.