23.8: Lanthanides

- Page ID

- 24348

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Lanthanides consist of the elements in the f-block of period six in the periodic table. While these metals can be considered transition metals, they have properties that set them apart from the rest of the elements.

Introduction

Lanthanides (elements 57–71) are fairly abundant in the earth’s crust, despite their historic characterization as rare earth elements. Thulium, the rarest naturally occurring lanthanoid, is more common in the earth’s crust than silver (4.5 × 10−5% versus 0.79 × 10−5% by mass). There are 17 rare earth elements, consisting of the 15 lanthanoids plus scandium and yttrium. They are called rare because they were once difficult to extract economically, so it was rare to have a pure sample; due to similar chemical properties, it is difficult to separate any one lanthanide from the others. However, newer separation methods, such as ion exchange resins similar to those found in home water softeners, make the separation of these elements easier and more economical. Most ores that contain these elements have low concentrations of all the rare earth elements mixed together.

Like any other series in the periodic table, such as the Alkali metals or the Halogens, the Lanthanides share many similar characteristics. These characteristics include the following:

- Similarity in physical properties throughout the series

- Adoption mainly of the +3 oxidation state. Usually found in crystalline compounds)

- They can also have an oxidation state of +2 or +4, though some lanthanides are most stable in the +3 oxidation state.

- Adoption of coordination numbers greater than 6 (usually 8-9) in compounds

- Tendency to decreasing coordination number across the series

- A preference for more electronegative elements (such as O or F) binding

- Very small crystal-field effects

- Little dependence on ligands

- Ionic complexes undergo rapid ligand-exchange

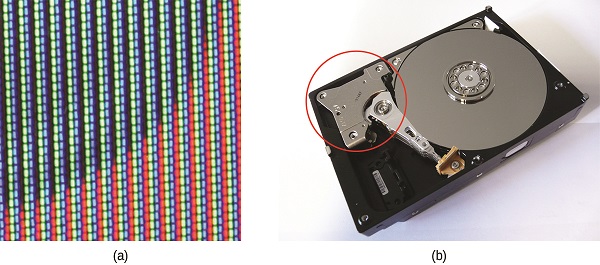

The commercial applications of lanthanides are growing rapidly. For example, europium is important in flat screen displays found in computer monitors, cell phones, and televisions. Neodymium is useful in laptop hard drives and in the processes that convert crude oil into gasoline (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Holmium is found in dental and medical equipment. In addition, many alternative energy technologies rely heavily on lanthanoids. Neodymium and dysprosium are key components of hybrid vehicle engines and the magnets used in wind turbines.

As the demand for lanthanide materials has increased faster than supply, prices have also increased. In 2008, dysprosium cost $110/kg; by 2014, the price had increased to $470/kg. Increasing the supply of lanthanoid elements is one of the most significant challenges facing the industries that rely on the optical and magnetic properties of these materials.

The transition elements have many properties in common with other metals. They are almost all hard, high-melting solids that conduct heat and electricity well. They readily form alloys and lose electrons to form stable cations. In addition, transition metals form a wide variety of stable coordination compounds, in which the central metal atom or ion acts as a Lewis acid and accepts one or more pairs of electrons. Many different molecules and ions can donate lone pairs to the metal center, serving as Lewis bases. In this chapter, we shall focus primarily on the chemical behavior of the elements of the first transition series.

Electron Configuration

Similarly, the Lanthanides have similarities in their electron configuration, which explains most of the physical similarities. These elements are different from the main group elements in the fact that they have electrons in the f orbital. After Lanthanum, the energy of the 4f sub-shell falls below that of the 5d sub-shell. This means that the electron start to fill the 4f sub-shell before the 5d sub-shell.

The electron configurations of these elements were primarily established through experiments (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The technique used is based on the fact that each line in an emission spectrum reveals the energy change involved in the transition of an electron from one energy level to another. However, the problem with this technique with respect to the Lanthanide elements is the fact that the 4f and 5d sub-shells have very similar energy levels, which can make it hard to tell the difference between the two.

| Symbol | Idealized | Observed | Symbol | Idealized | Observed |

| La | 5d16s2 | 5d16s2 | Tb | 4f85d16s2 | 4f9 6s2 or 4f85d16s2 |

| Ce | 4f15d16s2 | 4f15d16s2 | Dy | 4f95d16s2 | 4f10 6s2 |

| Pr | 4f25d16s2 | 4f3 6s2 | Ho | 4f105d16s2 | 4f11 6s2 |

| Nd | 4f35d16s2 | 4f4 6s2 | Er | 4f115d16s2 | 4f12 6s2 |

| Pm | 4f45d16s2 | 4f5 6s2 | Tm | 4f125d16s2 | 4f13 6s2 |

| Sm | 4f55d16s2 | 4f6 6s2 | Yb | 4f135d16s2 | 4f14 6s2 |

| Eu | 4f65d16s2 | 4f7 6s2 | Lu | 4f145d16s2 | 4f145d16s2 |

| Gd | 4f75d16s2 | 4f75d16s2 |

Another important feature of the Lanthanides is the Lanthanide Contraction, in which the 5s and 5p orbitals penetrate the 4f sub-shell. This means that the 4f orbital is not shielded from the increasing nuclear change, which causes the atomic radius of the atom to decrease that continues throughout the series.

Properties and Chemical Reactions

One property of the Lanthanides that affect how they will react with other elements is called the basicity. Basicity is a measure of the ease at which an atom will lose electrons. In another words, it would be the lack of attraction that a cation has for electrons or anions. For the Lanthanides, the basicity series is the following:

La3+ > Ce3+ > Pr3+ > Nd3+ > Pm3+ > Sm3+ > Eu3+ > Gd3+ > Tb3+ > Dy3+ > Ho3+ > Er3+ > Tm3+ > Yb3+ > Lu3+

In other words, the basicity decreases as the atomic number increases. Basicity differences are shown in the solubility of the salts and the formation of the complex species. Another property of the Lanthanides is their magnetic characteristics. The major magnetic properties of any chemical species are a result of the fact that each moving electron is a micromagnet. The species are either diamagnetic, meaning they have no unpaired electrons, or paramagnetic, meaning that they do have some unpaired electrons. The diamagnetic ions are: La3+, Lu3+, Yb2+ and Ce4+. The rest of the elements are paramagnetic.

| Symbol | Ionization Energy (kJ/mol) | Melting Point (°C) |

Boiling Point (°C) |

| La | 538 | 920 | 3469 |

| Ce | 527 | 795 | 3468 |

| Pr | 523 | 935 | 3127 |

| Nd | 529 | 1024 | 3027 |

| Pm | 536 | ||

| Sm | 543 | 1072 | 1900 |

| Eu | 546 | 826 | 1429 |

| Gd | 593 | 1312 | 3000 |

| Tb | 564 | 1356 | 2800 |

| Dy | 572 | 1407 | 2600 |

| Ho | 581 | 1461 | 2600 |

| Er | 589 | 1497 | 2900 |

| Tm | 597 | 1545 | 1727 |

| Yb | 603 | 824 | 1427 |

| Lu | 523 | 1652 | 3327 |

Metals and their Alloys

The metals have a silvery shine when freshly cut. However, they can tarnish quickly in air, especially Ce, La and Eu. These elements react with water slowly in cold, though that reaction can happen quickly when heated. This is due to their electropositive nature. The Lanthanides have the following reactions:

- oxidize rapidly in moist air

- dissolve quickly in acids

- reaction with oxygen is slow at room temperature, but they can ignite around 150-200 °C

- react with halogens upon heating

- upon heating, react with S, H, C and N

Periodic Trends: Size

The size of the atomic and ionic radii is determined by both the nuclear charge and by the number of electrons that are in the electronic shells. Within those shells, the degree of occupancy will also affect the size. In the Lanthanides, there is a decrease in atomic size from La to Lu. This decrease is known as the Lanthanide Contraction. The trend for the entire periodic table states that the atomic radius decreases as you travel from left to right. Therefore, the Lanthanides share this trend with the rest of the elements.

| Element | Atomic Radius (pm) | Ionic Radius (3+) | Element | Atomic Radius (pm) | Ionic Radius (3+) |

| La | 187.7 | 106.1 | Tb | 178.2 | 92.3 |

| Ce | 182 | 103.4 | Dy | 177.3 | 90.8 |

| Pr | 182.8 | 101.3 | Ho | 176.6 | 89.4 |

| Nd | 182.1 | 99.5 | Er | 175.7 | 88.1 |

| Pm | 181 | 97.9 | Tm | 174.6 | 89.4 |

| Sm | 180.2 | 96.4 | Yb | 194.0 | 85.8 |

| Eu | 204.2 | 95.0 | Lu | 173.4 | 84.8 |

| Gd | 180.2 | 93.8 |

Color and Light Absorbance

The color that a substance appears is the color that is reflected by the substance. This means that if a substance appears green, the green light is being reflected. The wavelength of the light determines if the light with be reflected or absorbed. Similarly, the splitting of the orbitals can affect the wavelength that can be absorbed (Table \(\PageIndex{4}\)). This is turn would be affected by the amount of unpaired electrons.

| Ion | Unpaired Electrons | Color | Ion | Unpaired Electrons | Color |

| La3+ | 0 | Colorless | Tb3+ | 6 | Pale Pink |

| Ce3+ | 1 | Colorless | Dy3+ | 5 | Yellow |

| Pr3+ | 2 | Green | Ho3+ | 4 | Pink; yellow |

| Nd3+ | 3 | Reddish | Er3+ | 3 | Reddish |

| Pm3+ | 4 | Pink; yellow | Tm3+ | 2 | Green |

| Sm3+ | 5 | Yellow | Yb3+ | 1 | Colorless |

| Eu3+ | 6 | Pale Pink | Lu3+ | 0 | Colorless |

| Gd3+ | 7 | Colorless |

Occurrence in Nature

Each known Lanthanide mineral contains all the members of the series. However, each mineral contains different concentrations of the individual Lanthanides. The three main mineral sources are the following:

- Monazite: contains mostly the lighter Lanthanides. The commercial mining of monazite sands in the United States is centered in Florida and the Carolinas

- Xenotime: contains mostly the heavier Lanthanides

- Euxenite: contains a fairly even distribution of the Lanthanides

In all the ores, the atoms with a even atomic number are more abundant. This allows for more nuclear stability, as explained in the Oddo-Harkins rule. The Oddo-Harkins rule simply states that the abundance of elements with an even atomic number is greater than the abundance of elements with an odd atomic number. In order to obtain these elements, the minerals must go through a separating process, known as separation chemistry. This can be done with selective reduction or oxidation. Another possibility is an ion-exchange method.

The abundance of elements with an even atomic number is greater than the abundance of elements with an odd atomic number.

Applications

The pure metals of the Lanthanides have little use. However, the alloys of the metals can be very useful. For example, the alloys of Cerium have been used for metallurgical applications due to their strong reducing abilities. The Lanthanides can also be used for ceramic purposes. The almost glass-like covering of a ceramic dish can be created with the lanthanides. They are also used to improve the intensity and color balance of arc lights.

Like the Actinides, the Lanthanides can be used for nuclear purposes. The hydrides can be used as hydrogen-moderator carriers. The oxides can be used as diluents in nuclear fields. The metals are good for being used as structural components. The can also be used for structural-alloy-modifying components of reactors. It is also possible for some elements, such as Tm, to be used as portable x-ray sources. Other elements, such as Eu, can be used as radiation sources.

References

- Petrucci, Hardwood, Herring. "General Chemistry: Principles & Modern Applications". New Jersey: Macmillan Publishing Company, 2007.

- Moeller, Therald. The Chemistry of the Lanthanides. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1963.

- Cotton, Simon. Lanthanides and Actinides. London: Macmillan Education Ltd, 1991.