9.8: Charles's Law

- Page ID

- 49443

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)While Boyle's Law explores the effect of pressure on the volume of a gas, Charles' Law examines the effect of temperature. Again you are probably familiar with the fact that increasing the temperature of a gas will cause the gas to expand. This effect was first studied quantitatively in 1787 by Jacques Charles (1746 to 1823) of France. Typical data from such an experiment are given in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). You can see that for 0.0466 mol H2(g) at constant pressure, a 50°C rise in temperature produces a 0.18-liter increase in volume, whether the temperature increases from 0.0 to 50.0° or from 100.0 to 150.0°C. While this experiment shows that temperature and volume are interrelated, it has deeper, more significant implications as well.

TABLE \(\PageIndex{1}\) Variation in the Volume of H2(g) with Temperature.

| Temperature (degree C) | Volume (L) |

|---|---|

| Data for 0.0446 mol H2(g) at 1 atm(101.3 kPa) | |

| 0.0 | 1.00 |

| 50.0 | 1.18 |

| 100.0 | 1.37 |

| 150.0 | 1.55 |

| Data for 0.100 mol H2(g) 1 atm (101.3 kPa) | |

| 0.0 | 2.24 |

| 50.0 | 2.65 |

| 100.0 | 3.06 |

| 150.0 | 3.47 |

The Kelvin Temperature Scale and Absolute Zero

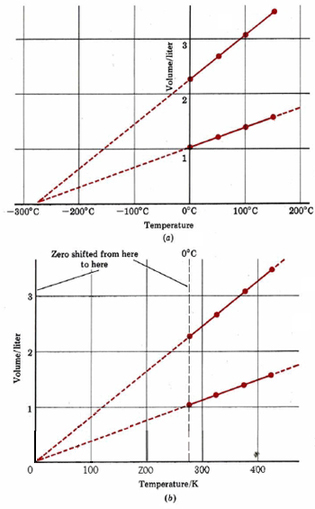

When the experimental data of Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) are graphed, we obtain Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Notice that the four points corresponding to 0.0446 mol H2(g) lie on a straight line, as do the points for 0.100 mol H2(g). If the lines are extrapolated (extended beyond the experimental points) to very low temperatures, we find that both of them intersect the horizontal axis at –273°C. The behavior of H2(g) (and of many other gases) at normal temperatures suggests that if we cool a gas sufficiently, its volume will become zero at –273°C.

Of course a real substance would condense to a liquid and freeze to a solid as it was cooled. When the pressure is 1.00 atm (101.3 kPa), H2(g) liquefies at –253°C and freezes at –259°C, and so all experiments involving would have to be performed above –253°C. If we could find a gas that did not condense, however, it would still be impossible to cool it below –273°C, because at that temperature its volume would be zero. Going to a lower temperature would correspond to a negative volume—something that is very hard to conceive of. Hence –273°C is referred to as the absolute zero of temperature—it is impossible to go any lower.

In Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) b the zero of the temperature axis has been shifted to absolute zero. The temperature scale used in this graph is called absolute or thermodynamic temperature. It is measured in SI units called Kelvins (abbreviated K), in honor of the English physicist William Thomson, Lord Kelvin (1824 to 1907).

The temperature interval 1 K corresponds to a change of 1°C, but zero on the thermodynamic scale is (0 K) is –273.15°C. The freezing point of water at 1.00 atm (101.3 kPa) pressure is thus 273.15 K. By shifting to the absolute temperature scale, we have simplified the graph of gas volume versus temperature.

Charles' Law

Figure 1b shows that the volume of a gas is directly proportional to its thermodynamic temperature, provided that the amount of gas and the pressure remain constant. This is known as Charles’ law, and can be expressed mathematically as where T represents the absolute temperature (usually measured in Kelvins).

\[V \propto T \nonumber \] As in the case of previous gas laws, we can introduce a proportionality constant, in this case, kC: \[V=k_{\text{C}}T\text{ or }\frac{V}{T}=k_{\text{C}}\text{ (2)} \nonumber \]

As an additional resource, the Concord Consortium has a tool that allows you to change the temperature of a gas in a container and observe the resulting change in volume. This tool can help to cement your understanding of Charles' Law and the relation between volume and temperature: Charles' Law Interactive.

A sample of H2(g) occupies a volume of 69.37 cm³ at a pressure of exactly 1 atm when immersed in a mixture of ice and water. When the gas (at the same pressure) is immersed in boiling benzene, its volume expands to 89.71 cm3. What is the boiling point of benzene?

Solution As in the case of Boyle’s law, two methods of solution are possible.

a) Algebraically, we have, from Eq. (2), \(\frac{V_{\text{1}}}{T_{\text{1}}}=k_{\text{C}}=\frac{V_{\text{2}}}{T_{\text{2}}}\) and substituting into the equation \(T_{\text{2}}=\frac{V_{\text{2}}T_{\text{1}}}{V_{\text{1}}}=\frac{\text{89}\text{.71 cm}^{\text{3}}\text{ }\times \text{ 273}\text{.15 K}}{\text{69}\text{.37 cm}^{\text{3}}}=\text{353}\text{.2 K}\) yields the desired result. (The ice-water mixture must be at 273.15 K, the freezing point of water.) b) By common sense we argue that since the gas expanded, its temperature must have increased. Thus \(T_{\text{2}}=\text{273}\text{.15 K }\times \text{ ration greater than 1}=\text{273}\text{.15 K }\times \text{ }\frac{\text{89}\text{.71 cm}^{\text{3}}}{\text{69}\text{.37 cm}^{\text{3}}}=\text{353}\text{.2 K}\) Note: In this example we have used the expansion of a gas instead of the expansion of liquid mercury to measure temperature.