8.6: Exceptions to the Octet Rule

- Page ID

- 38812

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- To understand why there are exceptions to the octet rule and what they are

General exceptions to the octet rule include molecules that have an odd number of electrons and molecules in which one or more atoms possess more or fewer than eight electrons. Molecules with an odd number of electrons are relatively rare in the s and p blocks but rather common among the d- and f-block elements. Compounds with more than an octet of electrons around an atom are called expanded-valence molecules. One model to explain their existence uses one or more d orbitals in bonding in addition to the valence ns and np orbitals. Such species are known for only atoms in period 3 or below, which contain nd subshells in their valence shell. Learning Objective is to assign a Lewis dot symbol to elements not having an octet of electrons in their compounds.

Lewis dot structures provide a simple model for rationalizing the bonding in most known compounds. However, there are three general exceptions to the octet rule:

- Molecules, such as NO, with an odd number of electrons;

- Molecules in which one or more atoms possess more than eight electrons, such as SF6; and

- Molecules such as BCl3, in which one or more atoms possess less than eight electrons.

Odd Number of Electrons

Because most molecules or ions that consist of s- and p-block elements contain even numbers of electrons, their bonding can be described using a model that assigns every electron to either a bonding pair or a lone pair. Molecules or ions containing d-block elements frequently contain an odd number of electrons, and their bonding cannot adequately be described using the simple approach we have developed so far. There are, however, a few molecules containing only p-block elements that have an odd number of electrons. Some important examples are nitric oxide (NO), whose biochemical importance was described in earlier chapters; nitrogen dioxide (NO2), an oxidizing agent in rocket propulsion; and chlorine dioxide (ClO2), which is used in water purification plants. Consider NO, for example. With 5 + 6 = 11 valence electrons, there is no way to draw a Lewis structure that gives each atom an octet of electrons. Molecules such as NO, NO2, and ClO2 require a more sophisticated treatment of bonding.

| Example 1: The \(NO\) Molecule |

|---|

|

Draw the Lewis structure for the molecule nitrous oxide (NO). Solution 1. Total electrons: 6+5=11 2. Bonding structure: 3. Octet on "outer" element: 4. Remainder of electrons (11-8 = 3) on "central" atom: 5. There are currently 5 valence electrons around the nitrogen. A double bond would place 7 around the nitrogen, and a triple bond would place 9 around the nitrogen. We appear unable to get an octet around each atom |

More Than an Octet of Electrons

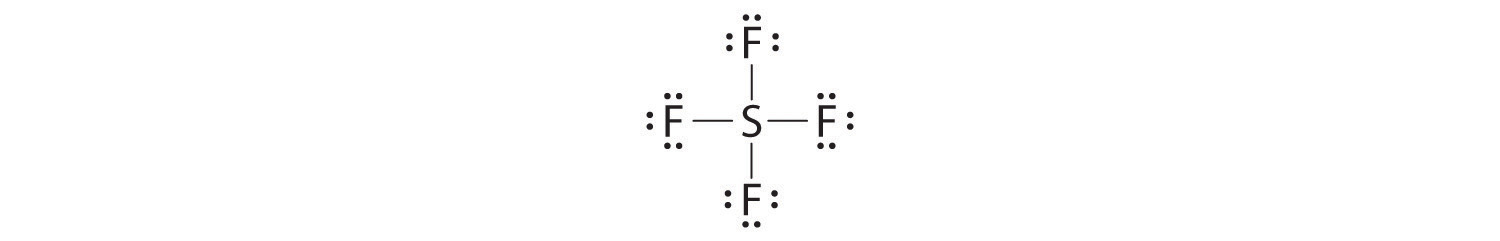

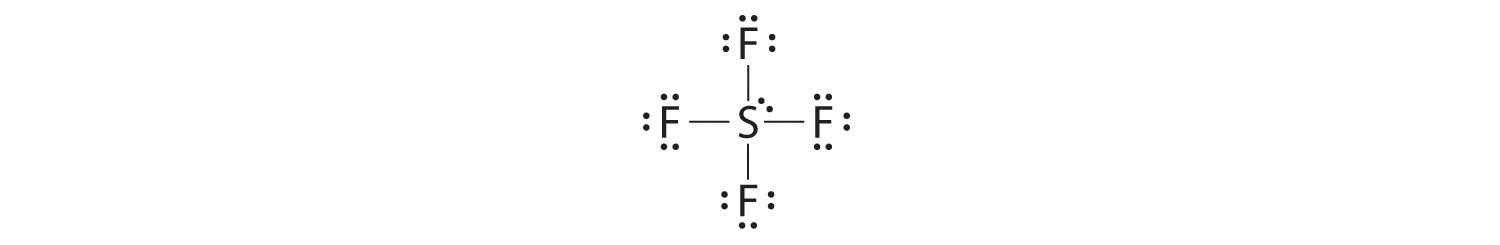

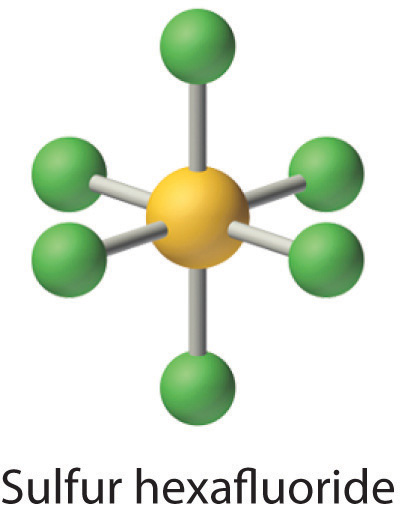

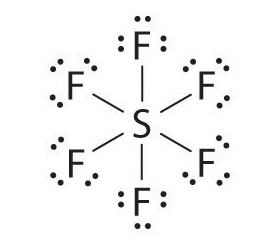

The most common exception to the octet rule is a molecule or an ion with at least one atom that possesses more than an octet of electrons. Such compounds are found for elements of period 3 and beyond. Examples from the p-block elements include SF6, a substance used by the electric power industry to insulate high-voltage lines, and the SO42− and PO43− ions.

Let’s look at sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), whose Lewis structure must accommodate a total of 48 valence electrons [6 + (6 × 7) = 48]. If we arrange the atoms and electrons symmetrically, we obtain a structure with six bonds to sulfur; that is, it is six-coordinate. Each fluorine atom has an octet, but the sulfur atom has 12 electrons surrounding it rather than 8.The third step in our procedure for writing Lewis electron structures, in which we place an electron pair between each pair of bonded atoms, requires that an atom have more than 8 electrons whenever it is bonded to more than 4 other atoms.

The octet rule is based on the fact that each valence orbital (typically, one ns and three np orbitals) can accommodate only two electrons. To accommodate more than eight electrons, sulfur must be using not only the ns and np valence orbitals but additional orbitals as well. Sulfur has an [Ne]3s23p43d0 electron configuration, so in principle it could accommodate more than eight valence electrons by using one or more d orbitals. Thus species such as SF6 are often called expanded-valence molecules. Whether or not such compounds really do use d orbitals in bonding is controversial, but this model explains why compounds exist with more than an octet of electrons around an atom.

There is no correlation between the stability of a molecule or an ion and whether or not it has an expanded valence shell. Some species with expanded valences, such as PF5, are highly reactive, whereas others, such as SF6, are very unreactive. In fact, SF6 is so inert that it has many commercial applications. In addition to its use as an electrical insulator, it is used as the coolant in some nuclear power plants, and it is the pressurizing gas in “unpressurized” tennis balls.

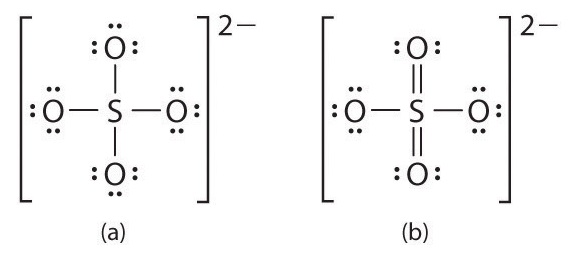

An expanded valence shell is often written for oxoanions of the heavier p-block elements, such as sulfate (SO42−) and phosphate (PO43−). Sulfate, for example, has a total of 32 valence electrons [6 + (4 × 6) + 2]. If we use a single pair of electrons to connect the sulfur and each oxygen, we obtain the four-coordinate Lewis structure (a). We know that sulfur can accommodate more than eight electrons by using its empty valence d orbitals, just as in SF6. An alternative structure (b) can be written with S=O double bonds, making the sulfur again six-coordinate. We can draw five other resonance structures equivalent to (b) that vary only in the arrangement of the single and double bonds. In fact, experimental data show that the S-to-O bonds in the SO42− ion are intermediate in length between single and double bonds, as expected for a system whose resonance structures all contain two S–O single bonds and two S=O double bonds. When calculating the formal charges on structures (a) and (b), we see that the S atom in (a) has a formal charge of +2, whereas the S atom in (b) has a formal charge of 0. Thus by using an expanded octet, a +2 formal charge on S can be eliminated.

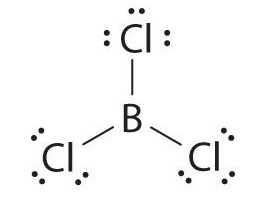

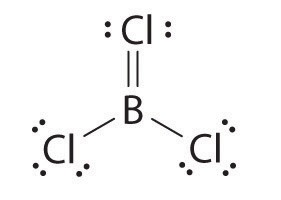

Less Than an Octet of Electrons

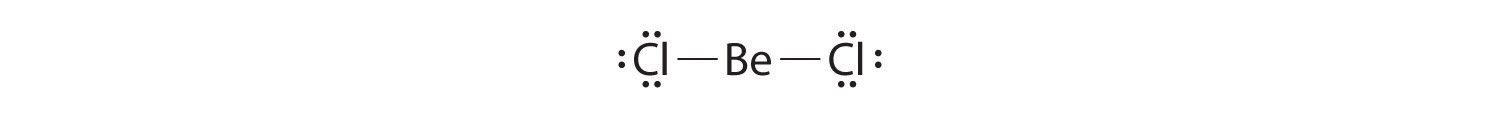

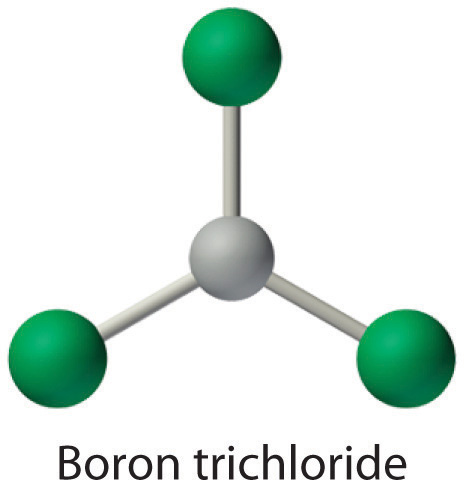

Molecules with atoms that possess less than an octet of electrons generally contain the lighter s- and p-block elements, especially beryllium, typically with just four electrons around the central atom, and boron, typically with six. One example, boron trichloride (BCl3) is used to produce fibers for reinforcing high-tech tennis rackets and golf clubs. The compound has 24 valence electrons and the following Lewis structure:

The boron atom has only six valence electrons, while each chlorine atom has eight. A reasonable solution might be to use a lone pair from one of the chlorine atoms to form a B-to-Cl double bond:

This resonance structure, however, results in a formal charge of +1 on the doubly bonded Cl atom and −1 on the B atom. The high electronegativity of Cl makes this separation of charge unlikely and suggests that this is not the most important resonance structure for BCl3. This conclusion is shown to be valid based on the three equivalent B–Cl bond lengths of 173 pm that have no double bond character. Electron-deficient compounds such as BCl3 have a strong tendency to gain an additional pair of electrons by reacting with species with a lone pair of electrons.

| Example 8 |

|---|

|

Draw Lewis dot structures for each compound.

Include resonance structures where appropriate. Given: two compounds Asked for: Lewis electron structures Strategy:

Solution:

|

| Exercise 8 |

|---|

|

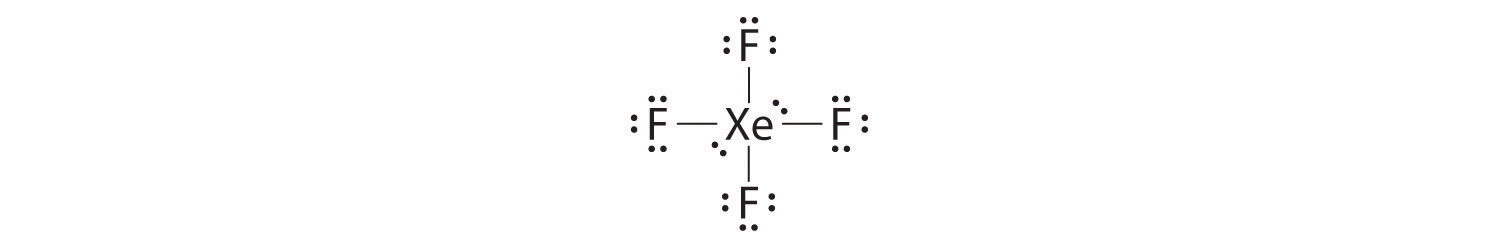

Draw Lewis dot structures for \(XeF_4\). Answer  |

| Note |

|---|

|