6.7: Risk perception

- Page ID

- 294578

6.7. Risk perception

Author: Fred Woudenberg

Reviewers: Ortwin Renn

Learning objectives:

- To list and memorize the most important determinants of risk perception

- To look at and try to understand the influence of risks in situations or activities which you or others encounter or undertake in daily life

- To actively look for as many situations and activities as possible in which the annual risk of getting sick, being injured or to die has little influence on risk perception

- To look for examples in which experts (if possible ask them) react like lay people in their own daily lives

Key words: Risk perception, fear, worry, risk, context

Introduction

If risk perception had a first law like toxicology has with Paracelsus' "Sola dosis facit venenum" (see section on History of Environmental Toxicology) it would be:

"People fear things that do not make them sick and get sick from things they do not fear."

People can, for instance, worry extremely over a newly discovered soil pollution site in their neighborhood, which they hear about at a public meeting they have come to with their diesel car, and, when returning home, light an extra cigarette without thinking to relieve the stress.

Sources: Left: File photo: Kalamazoo City Commissioner Don Cooney and Kalamazoo residents march to protest capping the Allied Paper Landfill, May 2013. https://www.wmuk.org/post/will-bioremediation-work-allied-microbial-ecologist-skeptical. Right: https://desmotivaciones.es/352654/Obama

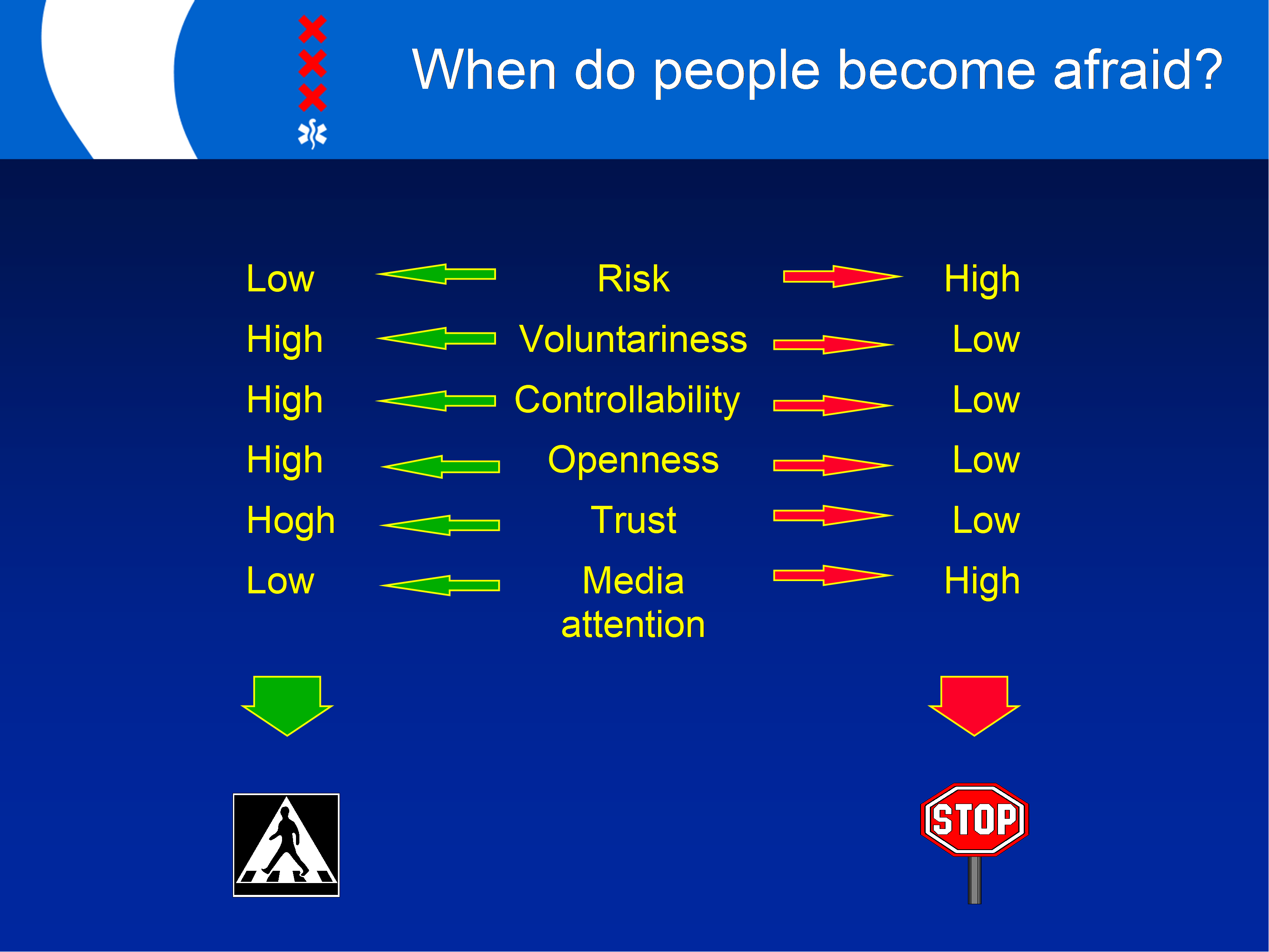

The explanation for this first law is quite easy. The annual risk of getting sick, being injured or to die has only limited influence on the perception of a risk. Other factors are more important. Figure 1 is a model of risk perception in its most basic form.

In the middle of this figure, there is a list with several factors which determine risk perception to a large extent. In any given situation, they can each end up at the left, safe side or on the right, dangerous side. The model is a simplification. Research since the late sixties of the previous century has led to a collection of many more factors that often are connected to each other (for lectures of some well-known researchers see examples 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5).

Why do people fear soil pollution?

An example can show this interconnection and the discrepancy between the annual health risks (at the top of Figure 1) and other factors. The risk of harmful health effects for people living on polluted soil is often very small. The factor 'risk' thus ends at the left, safe side. Most of the other factors end up at the right. People do not voluntary choose to have a soil pollution in their garden. They have absolutely no control over the situation and an eventual sanitation. For this, they depend on authorities and companies. Nowadays, trust in authorities and companies is very small. Many people will suspect that these authorities care more about their money than about the health and well-being of their citizens and neighbours. A newly discovered soil pollution will get local media attention and this will certainly be the case if there is controversy. If the untrusted authorities share their conclusion that the risks are low, many people will suspect that they withhold information and are not completely open. Especially saying that there is 'no cause for alarm' will only make people worry more (see a funny example). People will not believe the conclusion of authorities that the risk is low, so effectively all factors end up at the dangerous side.

Why smokers are not afraid

For smoking a cigarette, the evaluation is the other way around. Almost everybody knows that smoking is dangerous, but people light their cigarette themselves. Most people at least think they have control over their smoking habit as they can decide to stop at any moment (but being addicted, they probably highly overestimate their level of control). For their information or taking measures, people do not depend on others and no information is withheld about smoking. Some smokers suffer from what is called optimistic bias, the idea that misery only happens to other. They always have the example of their grandfather who started smoking at 12 and still ran the marathon at 85.

People can be upset if they learn that cigarette companies purposely make cigarettes more addictive. It makes them feel the company takes over control which people greatly resent. This, and not the health effects, can make people decide to quit smoking. This also explains why passive smoking is more effective than active smoking in influencing people's perceptions. Although the risk of passive smoking is 100 times smaller than the risk of active smoking, most factors end up at the right, dangerous side, making passive smoking maybe 100 times more objectionable and worrisome than active smoking.

Experts react like lay people at home

Many people are surprised to find out that the calculated or estimated health risks influences risk perception so little. But we experience it in our own daily lives, especially when we add another factor in the model: advantages. All of us perform risky activities because they are necessary, come with advantages or sometimes out of sheer fun. Most of us take part in daily traffic with an annual risk of dying far higher than 1 in a million. Once, twice or even more times a year we go on a holiday with a multitude of risks: transport, microbes, robbery, divorce. The thrill seekers of us go diving, mountain climbing, parachute jumping without even knowing the annual fatality rates. If the stakes are high, people can knowingly risk their life in order to improve it, as the thousands of immigrants trying to cross the Mediterranean illustrate, or even to give their life for a higher cause, like soldiers at war (Winston Churchill in 1940: "I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat").

An example at the other side can show it maybe even clearer. No matter how small the risk, it can be totally unacceptable and nonsensical. Suppose the government starts a new lottery with an extremely small chance of winning, say one in a billion. Every citizen must play and tickets are free. So far nothing strange, but there is a twitch. The main and only price of the lottery is a public execution broadcasted live on national TV. The government will probably not make itself very popular with this absurd lottery. When government, as still is done, tells people they have to accept a small risk because they accept larger risks of activities they choose themselves, it makes people feel they have been given a ticket in the above mentioned lottery. This is how people can feel if the government tells them the risk of the polluted soil they live on is extremely small and that it would be wiser for them to quit smoking.

All risks have a context

A main lesson which can be learned from the study of risk perception is that risks always occur in a context. A risk is always part of a situation or activity which has many more characteristics than only the chance of getting sick, being injured or to die. We do not judge risks, we judge situations and activities of which the risk is often only a small part. Risk perception occurs in a rich environment. After 50 years of research a lot has been discovered, but predicting how angry of afraid people will be in a new, unknown situation is still a daunting task.

Name at least 5 important determinants of risk perception.

Do people judge risks in isolation or the situation or activities they are part of?

How large in general is the influence of the risk on risk perception?

Do experts react differently from lay people if they encounter risks in their own daily lives?