Thyroid Hormone and CuI Dietary Supplement

- Page ID

- 50705

As we saw in The Amount of Substance: Moles, there is no relationship between the mass or volume of a substance and the number of molecules or atoms. In the case of nutritional additives like CuI, it is often necessary to know how many I atoms are present. So we then defined the amount of substance, n, to represent the number of particles (molecules or atoms). The amount is therefore useful in determining how much CuI for example, can be formed from a given quantity of I2 (or, as we'll see below, how much thyroid hormone can be made from a daily dose of CuI).

While 1 g of Cu, or 1 cm3 of Cu, reacts with a mass or volume of I2 that is not related to the coefficients of the chemical equation, 2 mol of Cu always reacts with 1 mol of I2 to give 2 mol of CuI, since two atoms of cu reacts with one molecule of I2 to give one CuI:

| 2 Cu (s) | + I2 (s) | → 2 CuI |

|---|---|---|

| 2 atoms | 1 molecule | 2 molecules |

| 1.00 g | 2.00 g | 3.00 g |

| 1.00 cm3 | 3.62 cm3 | 0.529 cm3 |

| 2.00 mol Cu | 1.00 mol I2 | 2.00 mol CuI |

What we need is a convenient way to convert masses to amounts, and the necessary conversion factor is called the molar mass. A molar quantity is one which has been divided by the amount of substance. For example, an extremely useful molar quantity is the molar mass M:

\[\begin{align}\large\text{Molar mass} &=\dfrac{\text{mass}}{\text{amount of substance}}\\ { } \\ \large M~\text{(g/mol)} ~&=~\dfrac{m~\text{(g)}}{n~\text{(mol)}} \end{align} \label{1}\]

It is often convenient to express physical quantities per unit amount of substance (per mole), because in this way equal numbers of atoms or molecules are being compared. Such molar quantities often tell us something about the atoms or molecules themselves. For example, if the molar volume of one solid is larger than that of another, it is reasonable to assume that the molecules of the first substance are larger than those of the second. (Comparing the molar volumes of liquids, and especially gases, would not necessarily give the same information since the molecules would not be as tightly packed.)

It is almost trivial to obtain the molar mass, since atomic and molecular weights expressed in grams give us the masses of 1 mol of substance.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Molar Mass

Obtain the molar mass of (a) Cu, (b) CuI, and (c) I2.

Solution

a) The atomic weight of copper is 63.55, and so 1 mol Cu weighs 63.55 g.

\[\text{M}_{Cu} = \dfrac{m_{Cu}}{n_{Cu}} = \dfrac{63.55 g}{1 mol} = \text{63.55} \dfrac{g}{mol}\nonumber\]

b) Similarly, for CuI, the molecular weight is 63.55 + 126.9 = 190.5, and so

\[\text{M}_{CuI} = \dfrac{m_{CuI}}{n_{CuI}} = \text{190.5} \dfrac{g}{mol}\nonumber\]

c) Similarly, for I2, the molecular weight is 2 x 126.9 = 253.8, and so

\[\text{M}_{I_2} = \dfrac{m_{I_2}}{n_{I_2}} = \text{253.8} \dfrac{g}{mol}\nonumber\]

The molar mass is numerically the same as the atomic or molecular weight, but it has units of grams per mole. The equation, which defines the molar mass, has the same form as those defining density, and the Avogadro constant. As in the case of density or the Avogadro constant, it is not necessary to memorize or manipulate a formula. Simply remember that mass and amount of substance are related via molar mass.

-

- \[\large\text{Mass }\overset{\text{Molar mass}}{\longleftrightarrow}\text{amount of substance }m\overset{M}{\longleftrightarrow}n\]

The molar mass is easily obtained from atomic weights and may be used as a conversion factor, provided the units cancel.

2

Calculate the amount of I2 in 500 g, and the number of I atoms.

Solution Any problem involving interconversion of mass and amount of substance requires molar mass; as we saw above,

\[\text{M} = 2\times 126.0 \dfrac{g}{mol} = 253.8 \dfrac{g}{mol}\nonumber\]

The amount of substance will be the mass times a conversion factor which permits cancellation of units:

\[n = m \times \text{conversion factor}\nonumber\]

\[m \times \dfrac{1}{M} = 500g \times \dfrac{1 mol}{253.8 g} = \text{1.97 mol I}_2 \nonumber\]

In this case the reciprocal of the molar mass was the appropriate conversion factor.

We can use the Avogadro constant to determine the number of I atoms, remembering that there are 2 atoms per molecule:

\[N = N_A \times n = 6.022 \times 10^{23} \text{mol} \times \text{1.97 mol I}_2 \times \dfrac{2 I atoms}{1 I_2 atom} = \text{2.37} \times 10^{24} \text{I atoms}\nonumber\]

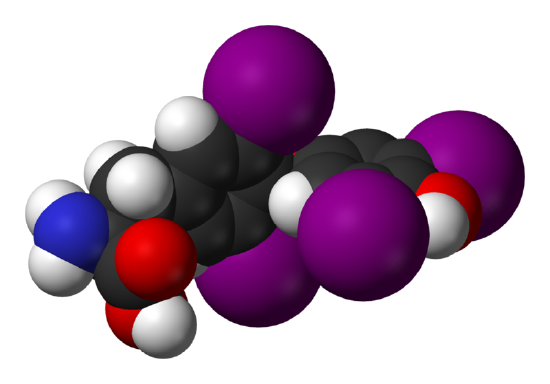

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Thyroxine

Dietary iodine is necessary for the synthesis of the thyroid hormone thyroxine (C15H11I4NO4, shown above, which has a molar mass of 776.87 g mol−1 and contains 4 iodine atoms per molecule. If a dose of CuI is 225 µg, it will supply enough I atoms for what mass of thyroxine?

First, use the molar mass to calculate the amount of CuI and I:

\(\text{n (mol)} = \dfrac{m (g)}{M(g/mol)} = 225 \times 10^{-6} g \times \dfrac{1 mol}{190.5 g} = 1.18 \times 10^{-6} \text{mol CuI}\)

\(1.18 \times 10^{-6} \text{mol CuI} \times \dfrac{\text{1 mol I}}{\text{1 mol CuI}} = 1.18 \times 10^{-6} \text{mol I}\)

But 1 mol Thyroxine requires 4 mol I, so:

\(1.18 \times 10^{-6} \text{mol I} \times \dfrac{\text{1 mol Thyroxine}}{\text{4 mol I}} = 2.95 \times 10^{-7} \text{mol Thyroxine}\)

Now use the molar mass of thyroxine to calculate the mass in grams:

\(\text{m (g)} = \text{n (mol)} \times \text{M (g/mol)} = 2.95 \times 10^{-7} \text{mol Thyroxine} \times 776.87 \dfrac{g}{mol} = 2.29 \times 10^{-4} \text{g Thyroxine, or 0.000229 g}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Carbon Tetrachloride

How many molecules would be present in 25.0 ml of pure carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)?

Solution In previous examples, we showed that the number of molecules may be obtained from the amount of substance by using the Avogadro constant. The amount of substance may be obtained from mass by using the molar mass, and mass from volume by means of density. A road map to the solution of this problem is

\(\large\text{Volume}\xrightarrow{\text{density}}\text{mass }\overset{\text{Molar mass}}{\longleftrightarrow}\text{amount}\overset{\text{Avogadro constant}}{\longleftrightarrow}\text{number of molecules}\)

or in shorthand notation

\(\large V\xrightarrow{\rho }m\xrightarrow{M}n\xrightarrow{\text{N}_{\text{A}}}N\)

The road map tells us that we must look up the density of CCl4:

ρ = 1.595 g cm–3

The molar mass must be calculated from the Table of Atomic Weights.

\(M = 12.01 + 4 \times 35.45 \dfrac{g}{mol} = 153.82 \dfrac{g}{mol}\)

and we recall that the Avogadro constant is

NA = 6.022 × 1023 mol–1

The last quantity (N) in the road map can then be obtained by starting with the first (V) and applying successive conversion factors:

\(\text{N} = 25.0 cm^3 \times \dfrac{1.595 g}{1 cm^3} \times \dfrac{1 mol}{153.81 g} \times \dfrac{6.022 \times 10^{23} \text{molecules}}{1 mol} = \text{1.56} \times 10^{23} \text{molecules}\)

Notice that in this problem we had to combine techniques from previous examples. To do this you must remember relationships among quantities. For example, a volume was given, and we knew it could be converted to the corresponding mass by means of density, and so we looked up the density in a table. By writing a road map, or at least seeing it in your mind’s eye, you can keep track of such relationships, determine what conversion factors are needed, and then use them to solve the problem.

From ChemPRIME: 2.10: The Molar Mass

Contributors and Attributions

Ed Vitz (Kutztown University), John W. Moore (UW-Madison), Justin Shorb (Hope College), Xavier Prat-Resina (University of Minnesota Rochester), Tim Wendorff, and Adam Hahn.