11.2: Intermolecular Forces

- Page ID

- 91233

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- To describe the intermolecular forces in liquids.

The properties of liquids are intermediate between those of gases and solids, but are more similar to solids. In contrast to intramolecular forces, such as the covalent bonds that hold atoms together in molecules and polyatomic ions, intermolecular forces hold molecules together in a liquid or solid. Intermolecular forces are generally much weaker than covalent bonds. For example, it requires 927 kJ to overcome the intramolecular forces and break both O–H bonds in 1 mol of water, but it takes only about 41 kJ to overcome the intermolecular attractions and convert 1 mol of liquid water to water vapor at 100°C. (Despite this seemingly low value, the intermolecular forces in liquid water are among the strongest such forces known!) Given the large difference in the strengths of intra- and intermolecular forces, changes between the solid, liquid, and gaseous states almost invariably occur for molecular substances without breaking covalent bonds.

The properties of liquids are intermediate between those of gases and solids but are more similar to solids.

Intermolecular forces determine bulk properties such as the melting points of solids and the boiling points of liquids. Liquids boil when the molecules have enough thermal energy to overcome the intermolecular attractive forces that hold them together, thereby forming bubbles of vapor within the liquid. Similarly, solids melt when the molecules acquire enough thermal energy to overcome the intermolecular forces that lock them into place in the solid.

Intermolecular forces are electrostatic in nature; that is, they arise from the interaction between positively and negatively charged species. Like covalent and ionic bonds, intermolecular interactions are the sum of both attractive and repulsive components. Because electrostatic interactions fall off rapidly with increasing distance between molecules, intermolecular interactions are most important for solids and liquids, where the molecules are close together. These interactions become important for gases only at very high pressures, where they are responsible for the observed deviations from the ideal gas law at high pressures. (For more information on the behavior of real gases and deviations from the ideal gas law,.)

In this section, we explicitly consider three kinds of intermolecular interactions:There are two additional types of electrostatic interaction that you are already familiar with: the ion–ion interactions that are responsible for ionic bonding and the ion–dipole interactions that occur when ionic substances dissolve in a polar substance such as water. The first two are often described collectively as van der Waals forces.

Dipole–Dipole Interactions

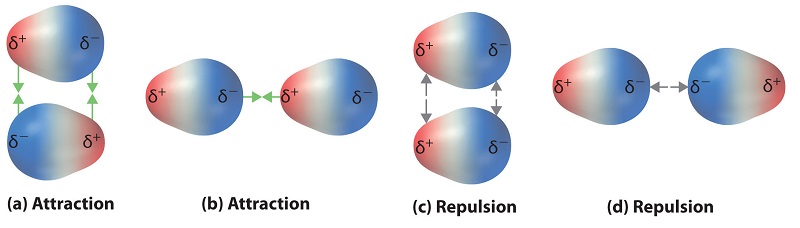

Polar covalent bonds behave as if the bonded atoms have localized fractional charges that are equal but opposite (i.e., the two bonded atoms generate a dipole). If the structure of a molecule is such that the individual bond dipoles do not cancel one another, then the molecule has a net dipole moment. Molecules with net dipole moments tend to align themselves so that the positive end of one dipole is near the negative end of another and vice versa, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1a}\).

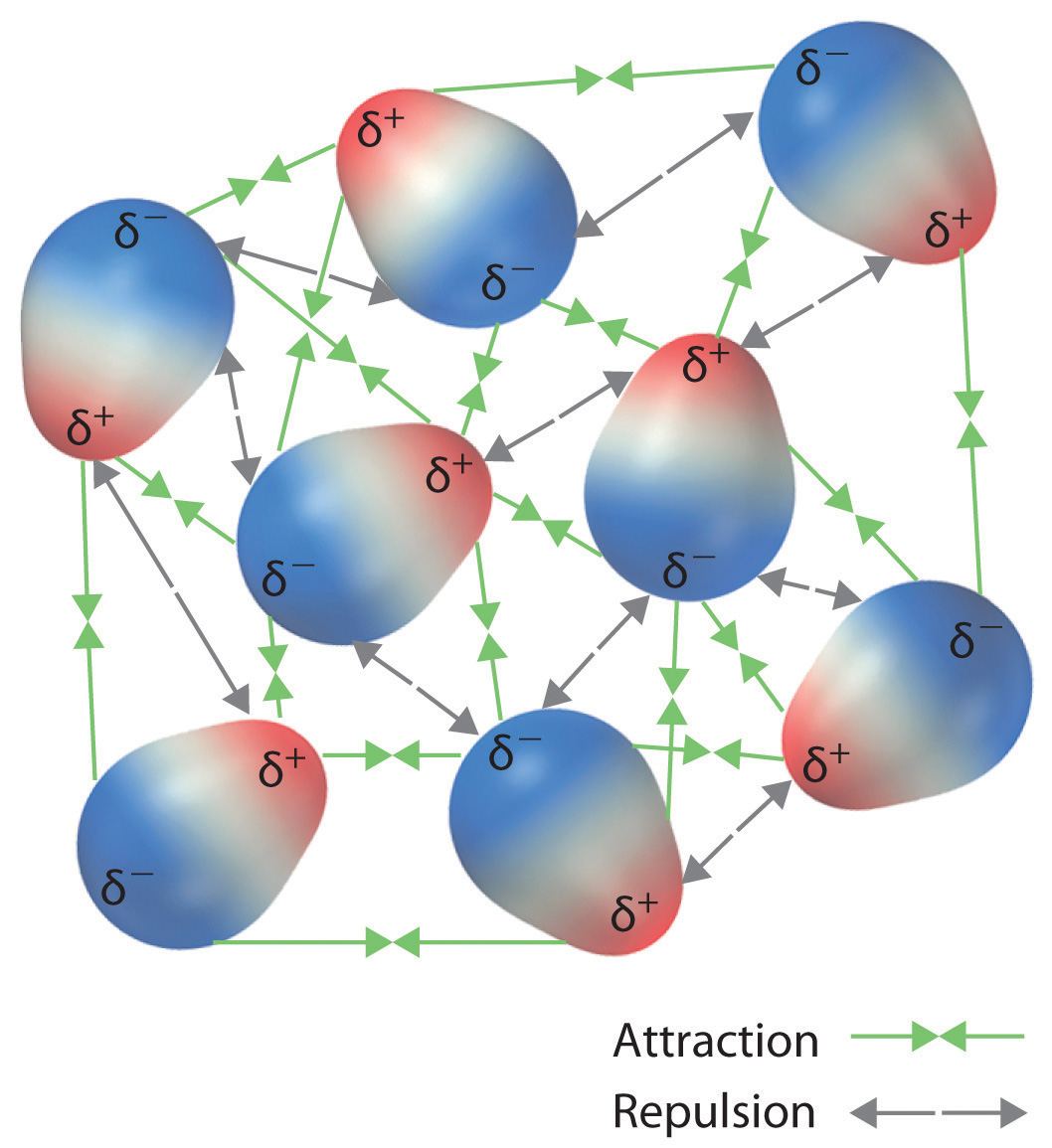

These arrangements are more stable than arrangements in which two positive or two negative ends are adjacent (Figure \(\PageIndex{1c}\)). Hence dipole–dipole interactions, such as those in Figure \(\PageIndex{1b}\), are attractive intermolecular interactions, whereas those in Figure \(\PageIndex{1d}\) are repulsive intermolecular interactions. Because molecules in a liquid move freely and continuously, molecules always experience both attractive and repulsive dipole–dipole interactions simultaneously, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\). On average, however, the attractive interactions dominate.

Because each end of a dipole possesses only a fraction of the charge of an electron, dipole–dipole interactions are substantially weaker than the interactions between two ions, each of which has a charge of at least ±1, or between a dipole and an ion, in which one of the species has at least a full positive or negative charge. In addition, the attractive interaction between dipoles falls off much more rapidly with increasing distance than do the ion–ion interactions. Recall that the attractive energy between two ions is proportional to 1/r, where r is the distance between the ions. Doubling the distance (r → 2r) decreases the attractive energy by one-half. In contrast, the energy of the interaction of two dipoles is proportional to 1/r6, so doubling the distance between the dipoles decreases the strength of the interaction by 26, or 64-fold. Thus a substance such as HCl, which is partially held together by dipole–dipole interactions, is a gas at room temperature and 1 atm pressure, whereas NaCl, which is held together by interionic interactions, is a high-melting-point solid. Within a series of compounds of similar molar mass, the strength of the intermolecular interactions increases as the dipole moment of the molecules increases, as shown in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). Using what we learned about predicting relative bond polarities from the electronegativities of the bonded atoms, we can make educated guesses about the relative boiling points of similar molecules.

| Compound | Molar Mass (g/mol) | Dipole Moment (D) | Boiling Point (K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C3H6 (cyclopropane) | 42 | 0 | 240 |

| CH3OCH3 (dimethyl ether) | 46 | 1.30 | 248 |

| CH3CN (acetonitrile) | 41 | 3.9 | 355 |

The attractive energy between two ions is proportional to 1/r, whereas the attractive energy between two dipoles is proportional to 1/r6.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

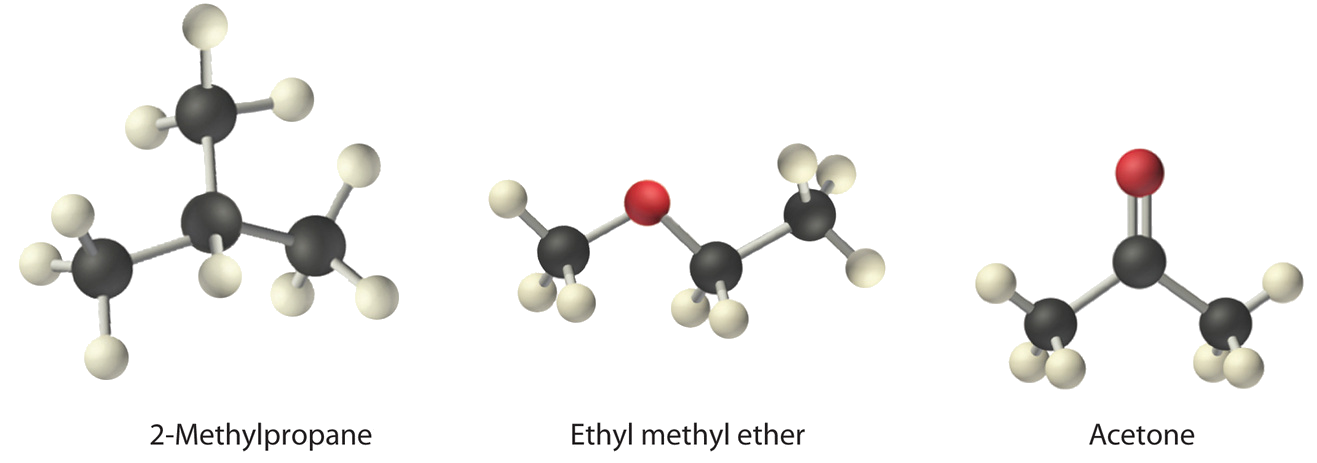

Arrange ethyl methyl ether (CH3OCH2CH3), 2-methylpropane [isobutane, (CH3)2CHCH3], and acetone (CH3COCH3) in order of increasing boiling points. Their structures are as follows:

Given: compounds

Asked for: order of increasing boiling points

Strategy:

Compare the molar masses and the polarities of the compounds. Compounds with higher molar masses and that are polar will have the highest boiling points.

Solution:

The three compounds have essentially the same molar mass (58–60 g/mol), so we must look at differences in polarity to predict the strength of the intermolecular dipole–dipole interactions and thus the boiling points of the compounds. The first compound, 2-methylpropane, contains only C–H bonds, which are not very polar because C and H have similar electronegativities. It should therefore have a very small (but nonzero) dipole moment and a very low boiling point. Ethyl methyl ether has a structure similar to H2O; it contains two polar C–O single bonds oriented at about a 109° angle to each other, in addition to relatively nonpolar C–H bonds. As a result, the C–O bond dipoles partially reinforce one another and generate a significant dipole moment that should give a moderately high boiling point. Acetone contains a polar C=O double bond oriented at about 120° to two methyl groups with nonpolar C–H bonds. The C–O bond dipole therefore corresponds to the molecular dipole, which should result in both a rather large dipole moment and a high boiling point. Thus we predict the following order of boiling points: 2-methylpropane < ethyl methyl ether < acetone. This result is in good agreement with the actual data: 2-methylpropane, boiling point = −11.7°C, and the dipole moment (μ) = 0.13 D; methyl ethyl ether, boiling point = 7.4°C and μ = 1.17 D; acetone, boiling point = 56.1°C and μ = 2.88 D.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Arrange carbon tetrafluoride (CF4), ethyl methyl sulfide (CH3SC2H5), dimethyl sulfoxide [(CH3)2S=O], and 2-methylbutane [isopentane, (CH3)2CHCH2CH3] in order of decreasing boiling points.

Answer: dimethyl sulfoxide (boiling point = 189.9°C) > ethyl methyl sulfide (boiling point = 67°C) > 2-methylbutane (boiling point = 27.8°C) > carbon tetrafluoride (boiling point = −128°C)

London Dispersion Forces

Thus far we have considered only interactions between polar molecules, but other factors must be considered to explain why many nonpolar molecules, such as bromine, benzene, and hexane, are liquids at room temperature, and others, such as iodine and naphthalene, are solids. Even the noble gases can be liquefied or solidified at low temperatures, high pressures, or both (Table \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

What kind of attractive forces can exist between nonpolar molecules or atoms? This question was answered by Fritz London (1900–1954), a German physicist who later worked in the United States. In 1930, London proposed that temporary fluctuations in the electron distributions within atoms and nonpolar molecules could result in the formation of short-lived instantaneous dipole moments, which produce attractive forces called London dispersion forces between otherwise nonpolar substances.

| Substance | Molar Mass (g/mol) | Melting Point (°C) | Boiling Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ar | 40 | −189.4 | −185.9 |

| Xe | 131 | −111.8 | −108.1 |

| N2 | 28 | −210 | −195.8 |

| O2 | 32 | −218.8 | −183.0 |

| F2 | 38 | −219.7 | −188.1 |

| I2 | 254 | 113.7 | 184.4 |

| CH4 | 16 | −182.5 | −161.5 |

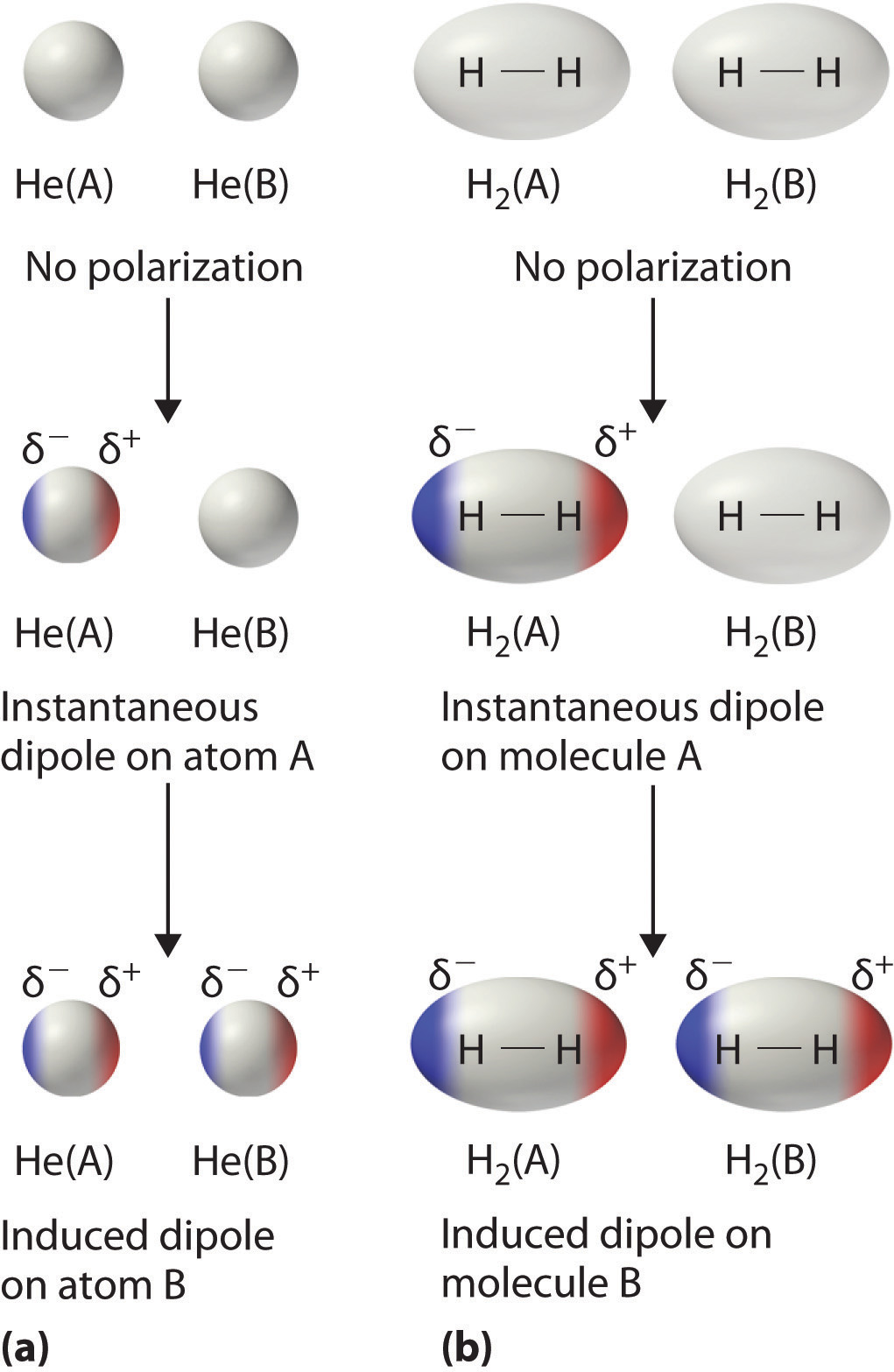

Consider a pair of adjacent He atoms, for example. On average, the two electrons in each He atom are uniformly distributed around the nucleus. Because the electrons are in constant motion, however, their distribution in one atom is likely to be asymmetrical at any given instant, resulting in an instantaneous dipole moment. As shown in part (a) in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), the instantaneous dipole moment on one atom can interact with the electrons in an adjacent atom, pulling them toward the positive end of the instantaneous dipole or repelling them from the negative end. The net effect is that the first atom causes the temporary formation of a dipole, called an induced dipole, in the second. Interactions between these temporary dipoles cause atoms to be attracted to one another. These attractive interactions are weak and fall off rapidly with increasing distance. London was able to show with quantum mechanics that the attractive energy between molecules due to temporary dipole–induced dipole interactions falls off as 1/r6. Doubling the distance therefore decreases the attractive energy by 26, or 64-fold.

Instantaneous dipole–induced dipole interactions between nonpolar molecules can produce intermolecular attractions just as they produce interatomic attractions in monatomic substances like Xe. This effect, illustrated for two H2 molecules in part (b) in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), tends to become more pronounced as atomic and molecular masses increase (Table \(\PageIndex{2}\)). For example, Xe boils at −108.1°C, whereas He boils at −269°C. The reason for this trend is that the strength of London dispersion forces is related to the ease with which the electron distribution in a given atom can be perturbed. In small atoms such as He, the two 1s electrons are held close to the nucleus in a very small volume, and electron–electron repulsions are strong enough to prevent significant asymmetry in their distribution. In larger atoms such as Xe, however, the outer electrons are much less strongly attracted to the nucleus because of filled intervening shells. As a result, it is relatively easy to temporarily deform the electron distribution to generate an instantaneous or induced dipole. The ease of deformation of the electron distribution in an atom or molecule is called its polarizability. Because the electron distribution is more easily perturbed in large, heavy species than in small, light species, we say that heavier substances tend to be much more polarizable than lighter ones.

For similar substances, London dispersion forces get stronger with increasing molecular size.

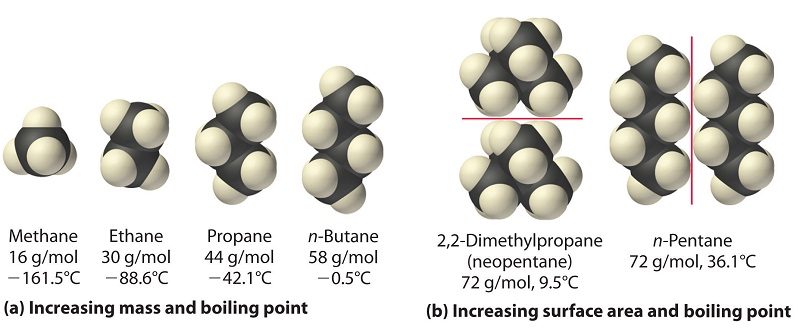

The polarizability of a substance also determines how it interacts with ions and species that possess permanent dipoles. Thus London dispersion forces are responsible for the general trend toward higher boiling points with increased molecular mass and greater surface area in a homologous series of compounds, such as the alkanes (part (a) in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The strengths of London dispersion forces also depend significantly on molecular shape because shape determines how much of one molecule can interact with its neighboring molecules at any given time. For example, part (b) in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) shows 2,2-dimethylpropane (neopentane) and n-pentane, both of which have the empirical formula C5H12. Neopentane is almost spherical, with a small surface area for intermolecular interactions, whereas n-pentane has an extended conformation that enables it to come into close contact with other n-pentane molecules. As a result, the boiling point of neopentane (9.5°C) is more than 25°C lower than the boiling point of n-pentane (36.1°C).

All molecules, whether polar or nonpolar, are attracted to one another by London dispersion forces in addition to any other attractive forces that may be present. In general, however, dipole–dipole interactions in small polar molecules are significantly stronger than London dispersion forces, so the former predominate.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Arrange n-butane, propane, 2-methylpropane [isobutene, (CH3)2CHCH3], and n-pentane in order of increasing boiling points.

Given: compounds

Asked for: order of increasing boiling points

Strategy:

Determine the intermolecular forces in the compounds and then arrange the compounds according to the strength of those forces. The substance with the weakest forces will have the lowest boiling point.

Solution:

The four compounds are alkanes and nonpolar, so London dispersion forces are the only important intermolecular forces. These forces are generally stronger with increasing molecular mass, so propane should have the lowest boiling point and n-pentane should have the highest, with the two butane isomers falling in between. Of the two butane isomers, 2-methylpropane is more compact, and n-butane has the more extended shape. Consequently, we expect intermolecular interactions for n-butane to be stronger due to its larger surface area, resulting in a higher boiling point. The overall order is thus as follows, with actual boiling points in parentheses: propane (−42.1°C) < 2-methylpropane (−11.7°C) < n-butane (−0.5°C) < n-pentane (36.1°C).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Arrange GeH4, SiCl4, SiH4, CH4, and GeCl4 in order of decreasing boiling points.

Answer

GeCl4 (87°C) > SiCl4 (57.6°C) > GeH4 (−88.5°C) > SiH4 (−111.8°C) > CH4 (−161°C)

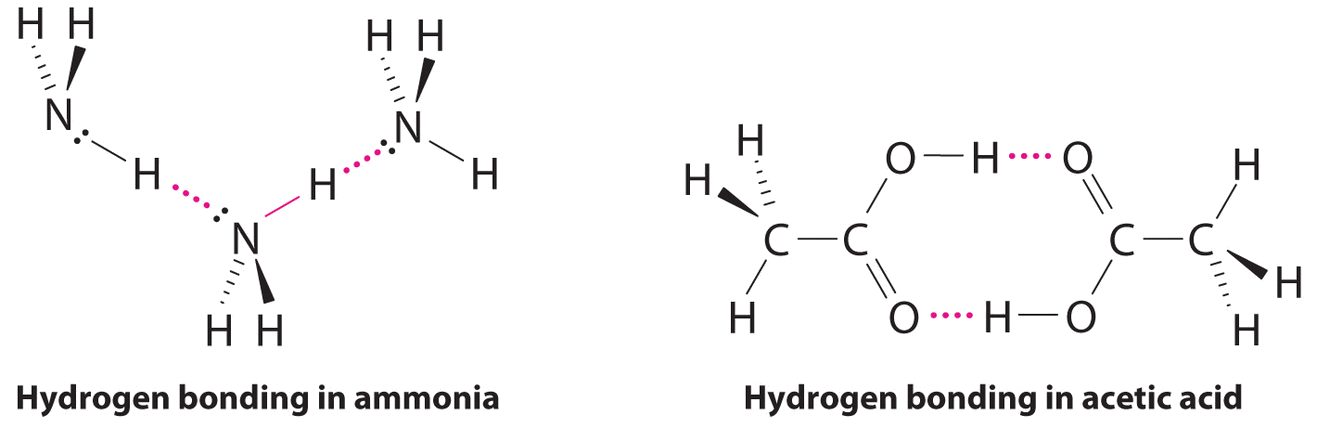

Hydrogen Bonds

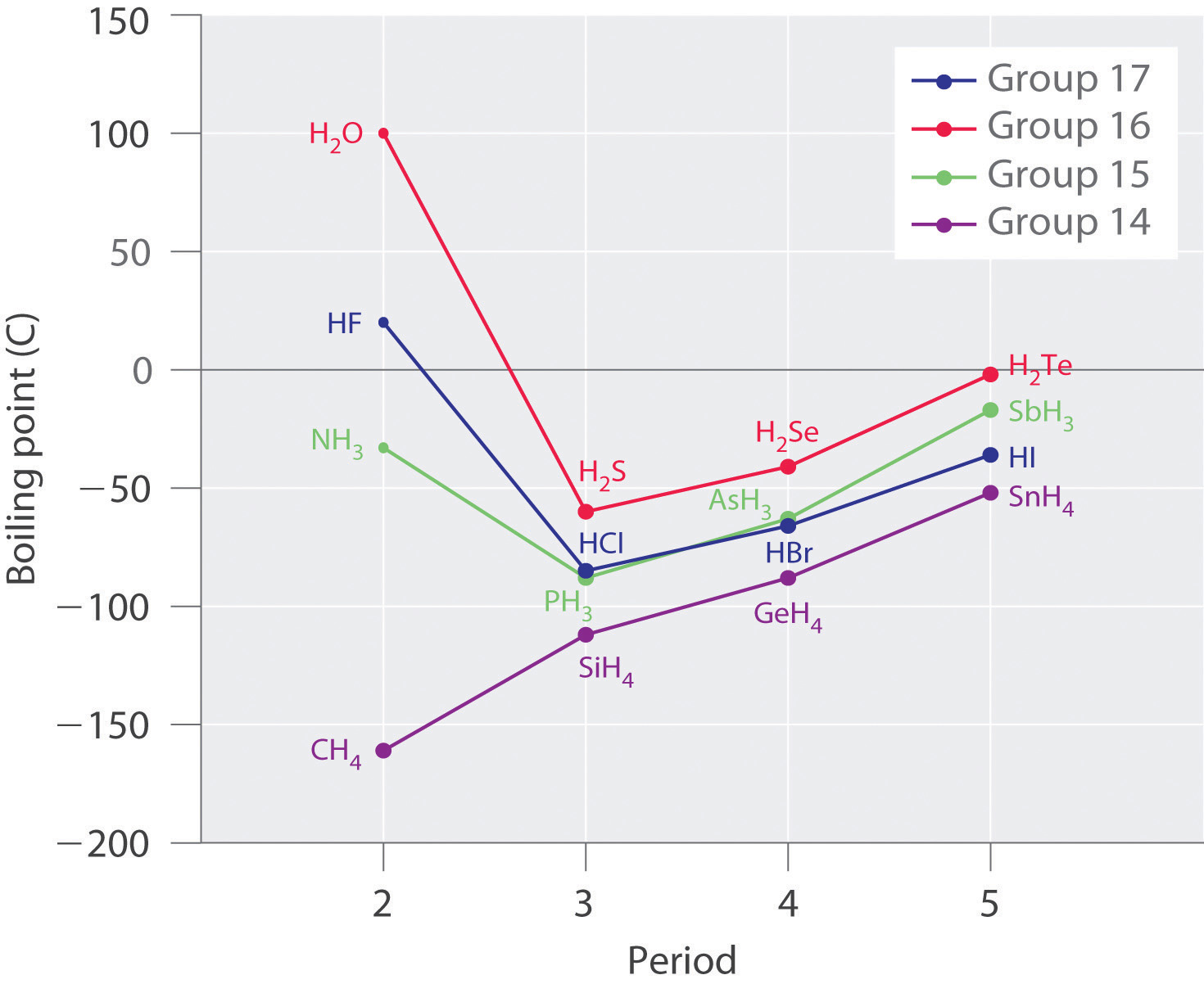

Molecules with hydrogen atoms bonded to electronegative atoms such as O, N, and F (and to a much lesser extent Cl and S) tend to exhibit unusually strong intermolecular interactions. These result in much higher boiling points than are observed for substances in which London dispersion forces dominate, as illustrated for the covalent hydrides of elements of groups 14–17 in Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\). Methane and its heavier congeners in group 14 form a series whose boiling points increase smoothly with increasing molar mass. This is the expected trend in nonpolar molecules, for which London dispersion forces are the exclusive intermolecular forces. In contrast, the hydrides of the lightest members of groups 15–17 have boiling points that are more than 100°C greater than predicted on the basis of their molar masses. The effect is most dramatic for water: if we extend the straight line connecting the points for H2Te and H2Se to the line for period 2, we obtain an estimated boiling point of −130°C for water! Imagine the implications for life on Earth if water boiled at −130°C rather than 100°C.

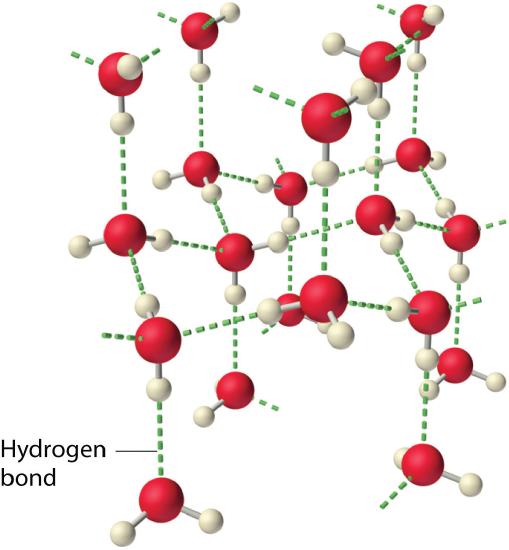

Why do strong intermolecular forces produce such anomalously high boiling points and other unusual properties, such as high enthalpies of vaporization and high melting points? The answer lies in the highly polar nature of the bonds between hydrogen and very electronegative elements such as O, N, and F. The large difference in electronegativity results in a large partial positive charge on hydrogen and a correspondingly large partial negative charge on the O, N, or F atom. Consequently, H–O, H–N, and H–F bonds have very large bond dipoles that can interact strongly with one another. Because a hydrogen atom is so small, these dipoles can also approach one another more closely than most other dipoles. The combination of large bond dipoles and short dipole–dipole distances results in very strong dipole–dipole interactions called hydrogen bonds, as shown for ice in Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\). A hydrogen bond is usually indicated by a dotted line between the hydrogen atom attached to O, N, or F (the hydrogen bond donor) and the atom that has the lone pair of electrons (the hydrogen bond acceptor). Because each water molecule contains two hydrogen atoms and two lone pairs, a tetrahedral arrangement maximizes the number of hydrogen bonds that can be formed. In the structure of ice, each oxygen atom is surrounded by a distorted tetrahedron of hydrogen atoms that form bridges to the oxygen atoms of adjacent water molecules. The bridging hydrogen atoms are not equidistant from the two oxygen atoms they connect, however. Instead, each hydrogen atom is 101 pm from one oxygen and 174 pm from the other. In contrast, each oxygen atom is bonded to two H atoms at the shorter distance and two at the longer distance, corresponding to two O–H covalent bonds and two O⋅⋅⋅H hydrogen bonds from adjacent water molecules, respectively. The resulting open, cagelike structure of ice means that the solid is actually slightly less dense than the liquid, which explains why ice floats on water rather than sinks.

Each water molecule accepts two hydrogen bonds from two other water molecules and donates two hydrogen atoms to form hydrogen bonds with two more water molecules, producing an open, cagelike structure. The structure of liquid water is very similar, but in the liquid, the hydrogen bonds are continually broken and formed because of rapid molecular motion.

Hydrogen bond formation requires both a hydrogen bond donor and a hydrogen bond acceptor.

Because ice is less dense than liquid water, rivers, lakes, and oceans freeze from the top down. In fact, the ice forms a protective surface layer that insulates the rest of the water, allowing fish and other organisms to survive in the lower levels of a frozen lake or sea. If ice were denser than the liquid, the ice formed at the surface in cold weather would sink as fast as it formed. Bodies of water would freeze from the bottom up, which would be lethal for most aquatic creatures. The expansion of water when freezing also explains why automobile or boat engines must be protected by “antifreeze” and why unprotected pipes in houses break if they are allowed to freeze.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Considering CH3OH, C2H6, Xe, and (CH3)3N, which can form hydrogen bonds with themselves? Draw the hydrogen-bonded structures.

Given: compounds

Asked for: formation of hydrogen bonds and structure

Strategy:

- Identify the compounds with a hydrogen atom attached to O, N, or F. These are likely to be able to act as hydrogen bond donors.

- Of the compounds that can act as hydrogen bond donors, identify those that also contain lone pairs of electrons, which allow them to be hydrogen bond acceptors. If a substance is both a hydrogen donor and a hydrogen bond acceptor, draw a structure showing the hydrogen bonding.

Solution:

A Of the species listed, xenon (Xe), ethane (C2H6), and trimethylamine [(CH3)3N] do not contain a hydrogen atom attached to O, N, or F; hence they cannot act as hydrogen bond donors.

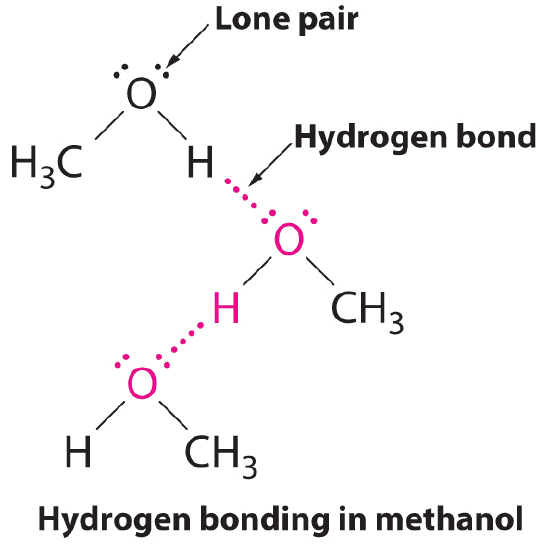

B The one compound that can act as a hydrogen bond donor, methanol (CH3OH), contains both a hydrogen atom attached to O (making it a hydrogen bond donor) and two lone pairs of electrons on O (making it a hydrogen bond acceptor); methanol can thus form hydrogen bonds by acting as either a hydrogen bond donor or a hydrogen bond acceptor. The hydrogen-bonded structure of methanol is as follows:

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Considering CH3CO2H, (CH3)3N, NH3, and CH3F, which can form hydrogen bonds with themselves? Draw the hydrogen-bonded structures.

Answer

CH3CO2H and NH3;

Although hydrogen bonds are significantly weaker than covalent bonds, with typical dissociation energies of only 15–25 kJ/mol, they have a significant influence on the physical properties of a compound. Compounds such as HF can form only two hydrogen bonds at a time as can, on average, pure liquid NH3. Consequently, even though their molecular masses are similar to that of water, their boiling points are significantly lower than the boiling point of water, which forms four hydrogen bonds at a time.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Buckyballs

Arrange C60 (buckminsterfullerene, which has a cage structure), NaCl, He, Ar, and N2O in order of increasing boiling points.

Given: compounds

Asked for: order of increasing boiling points

Strategy:

Identify the intermolecular forces in each compound and then arrange the compounds according to the strength of those forces. The substance with the weakest forces will have the lowest boiling point.

Solution:

Electrostatic interactions are strongest for an ionic compound, so we expect NaCl to have the highest boiling point. To predict the relative boiling points of the other compounds, we must consider their polarity (for dipole–dipole interactions), their ability to form hydrogen bonds, and their molar mass (for London dispersion forces). Helium is nonpolar and by far the lightest, so it should have the lowest boiling point. Argon and N2O have very similar molar masses (40 and 44 g/mol, respectively), but N2O is polar while Ar is not. Consequently, N2O should have a higher boiling point. A C60 molecule is nonpolar, but its molar mass is 720 g/mol, much greater than that of Ar or N2O. Because the boiling points of nonpolar substances increase rapidly with molecular mass, C60 should boil at a higher temperature than the other nonionic substances. The predicted order is thus as follows, with actual boiling points in parentheses: He (−269°C) < Ar (−185.7°C) < N2O (−88.5°C) < C60 (>280°C) < NaCl (1465°C).

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Arrange 2,4-dimethylheptane, Ne, CS2, Cl2, and KBr in order of decreasing boiling points.

Answer: KBr (1435°C) > 2,4-dimethylheptane (132.9°C) > CS2 (46.6°C) > Cl2 (−34.6°C) > Ne (−246°C)

Summary

Intermolecular forces are electrostatic in nature and include van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds. Molecules in liquids are held to other molecules by intermolecular interactions, which are weaker than the intramolecular interactions that hold the atoms together within molecules and polyatomic ions. Transitions between the solid and liquid or the liquid and gas phases are due to changes in intermolecular interactions but do not affect intramolecular interactions. The three major types of intermolecular interactions are dipole–dipole interactions, London dispersion forces (these two are often referred to collectively as van der Waals forces), and hydrogen bonds. Dipole–dipole interactions arise from the electrostatic interactions of the positive and negative ends of molecules with permanent dipole moments; their strength is proportional to the magnitude of the dipole moment and to 1/r6, where r is the distance between dipoles. London dispersion forces are due to the formation of instantaneous dipole moments in polar or nonpolar molecules as a result of short-lived fluctuations of electron charge distribution, which in turn cause the temporary formation of an induced dipole in adjacent molecules. Like dipole–dipole interactions, their energy falls off as 1/r6. Larger atoms tend to be more polarizable than smaller ones because their outer electrons are less tightly bound and are therefore more easily perturbed. Hydrogen bonds are especially strong dipole–dipole interactions between molecules that have hydrogen bonded to a highly electronegative atom, such as O, N, or F. The resulting partially positively charged H atom on one molecule (the hydrogen bond donor) can interact strongly with a lone pair of electrons of a partially negatively charged O, N, or F atom on adjacent molecules (the hydrogen bond acceptor). Because of strong O⋅⋅⋅H hydrogen bonding between water molecules, water has an unusually high boiling point, and ice has an open, cagelike structure that is less dense than liquid water.