1.3: Lewis Structures

- Page ID

- 28097

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Using Lewis Dot Symbols to Describe Covalent Bonding

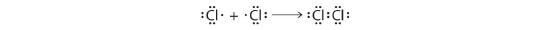

This sharing of electrons allowing atoms to "stick" together is the basis of covalent bonding. There is some intermediate distant, generally a bit longer than 0.1 nm, or if you prefer 100 pm, at which the attractive forces significantly outweigh the repulsive forces and a bond will be formed if both atoms can achieve a completen s2np6 configuration. It is this behavior that Lewis captured in his octet rule. The valence electron configurations of the constituent atoms of a covalent compound are important factors in determining its structure, stoichiometry, and properties. For example, chlorine, with seven valence electrons, is one electron short of an octet. If two chlorine atoms share their unpaired electrons by making a covalent bond and forming Cl2, they can each complete their valence shell:

Each chlorine atom now has an octet. The electron pair being shared by the atoms is called a bonding pair ; the other three pairs of electrons on each chlorine atom are called lone pairs. Lone pairs are not involved in covalent bonding. If both electrons in a covalent bond come from the same atom, the bond is called a coordinate covalent bond.![]()

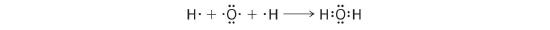

We can illustrate the formation of a water molecule from two hydrogen atoms and an oxygen atom using Lewis dot symbols:

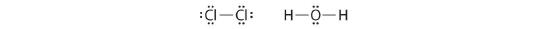

The structure on the right is the Lewis electron structure, or Lewis structure, for H2O. With two bonding pairs and two lone pairs, the oxygen atom has now completed its octet. Moreover, by sharing a bonding pair with oxygen, each hydrogen atom now has a full valence shell of two electrons. Chemists usually indicate a bonding pair by a single line, as shown here for our two examples:

The following procedure can be used to construct Lewis electron structures for more complex molecules and ions:

- Arrange the atoms to show specific connections. When there is a central atom, it is usually the least electronegative element in the compound. Chemists usually list this central atom first in the chemical formula (as in CCl4 and CO32−, which both have C as the central atom), which is another clue to the compound’s structure. Hydrogen and the halogens are almost always connected to only one other atom, so they are usually terminal rather than central.

Note

The central atom is usually the least electronegative element in the molecule or ion; hydrogen and the halogens are usually terminal.

- Determine the total number of valence electrons in the molecule or ion. Add together the valence electrons from each atom. (Recall from Chapter 2 that the number of valence electrons is indicated by the position of the element in the periodic table.) If the species is a polyatomic ion, remember to add or subtract the number of electrons necessary to give the total charge on the ion. For CO32−, for example, we add two electrons to the total because of the −2 charge.

- Place a bonding pair of electrons between each pair of adjacent atoms to give a single bond. In \(H_2O\), for example, there is a bonding pair of electrons between oxygen and each hydrogen.

- Beginning with the terminal atoms, add enough electrons to each atom to give each atom an octet (two for hydrogen). These electrons will usually be lone pairs.

- If any electrons are left over, place them on the central atom. Some atoms are able to accommodate more than eight electrons.

- If the central atom has fewer electrons than an octet, use lone pairs from terminal atoms to form multiple (double or triple) bonds to the central atom to achieve an octet. This will not change the number of electrons on the terminal atoms.

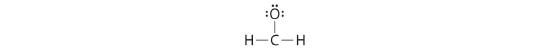

Now let’s apply this procedure to some particular compounds, beginning with one we have already discussed.![]()

2. Each H atom (group 1) has 1 valence electron, and the O atom (group 16) has 6 valence electrons, for a total of 8 valence electrons.![]()

3. Placing one bonding pair of electrons between the O atom and each H atom gives H:O:H, with 4 electrons left over.![]()

4. Each H atom has a full valence shell of 2 electrons.![]()

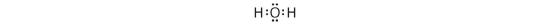

5. Adding the remaining 4 electrons to the oxygen (as two lone pairs) gives the following structure:

This is the Lewis structure we drew earlier. Because it gives oxygen an octet and each hydrogen two electrons, we do not need to use step 6.

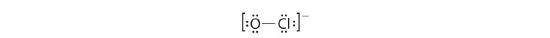

2. Oxygen (group 16) has 6 valence electrons, and chlorine (group 17) has 7 valence electrons; we must add one more for the negative charge on the ion, giving a total of 14 valence electrons.

3. Placing a bonding pair of electrons between O and Cl gives O:Cl, with 12 electrons left over.

4. If we place six electrons (as three lone pairs) on each atom, we obtain the following structure:

Each atom now has an octet of electrons, so steps 5 and 6 are not needed. The Lewis electron structure is drawn within brackets as is customary for an ion, with the overall charge indicated outside the brackets, and the bonding pair of electrons is indicated by a solid line. OCl− is the hypochlorite ion, the active ingredient in chlorine laundry bleach and swimming pool disinfectant.

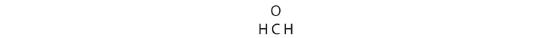

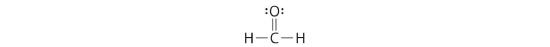

1. Because carbon is less electronegative than oxygen and hydrogen is normally terminal, C must be the central atom. One possible arrangement is as follows:

2. Each hydrogen atom (group 1) has one valence electron, carbon (group 14) has 4 valence electrons, and oxygen (group 16) has 6 valence electrons, for a total of [(2)(1) + 4 + 6] = 12 valence electrons.

3. Placing a bonding pair of electrons between each pair of bonded atoms gives the following:

Six electrons are used, and 6 are left over.

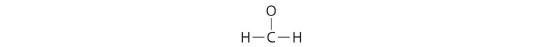

4. Adding all 6 remaining electrons to oxygen (as three lone pairs) gives the following:

Although oxygen now has an octet and each hydrogen has 2 electrons, carbon has only 6 electrons.

5. There are no electrons left to place on the central atom.

6. To give carbon an octet of electrons, we use one of the lone pairs of electrons on oxygen to form a carbon–oxygen double bond:

Both the oxygen and the carbon now have an octet of electrons, so this is an acceptable Lewis electron structure. The O has two bonding pairs and two lone pairs, and C has four bonding pairs. This is the structure of formaldehyde, which is used in embalming fluid.

An alternative structure can be drawn with one H bonded to O. Formal charges, discussed later in this section, suggest that such a structure is less stable than that shown previously.![]()

Example

Write the Lewis electron structure for each species.

- NCl3

- S22−

- NOCl

Given: chemical species

Asked for: Lewis electron structures

Strategy:

Use the six-step procedure to write the Lewis electron structure for each species.

Solution:

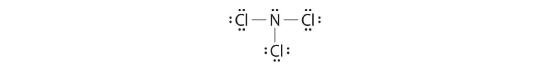

Nitrogen is less electronegative than chlorine, and halogen atoms are usually terminal, so nitrogen is the central atom. The nitrogen atom (group 15) has 5 valence electrons and each chlorine atom (group 17) has 7 valence electrons, for a total of 26 valence electrons. Using 2 electrons for each N–Cl bond and adding three lone pairs to each Cl account for (3 × 2) + (3 × 2 × 3) = 24 electrons. Rule 5 leads us to place the remaining 2 electrons on the central N:

Nitrogen trichloride is an unstable oily liquid once used to bleach flour; this use is now prohibited in the United States.

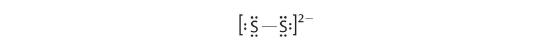

-

In a diatomic molecule or ion, we do not need to worry about a central atom. Each sulfur atom (group 16) contains 6 valence electrons, and we need to add 2 electrons for the −2 charge, giving a total of 14 valence electrons. Using 2 electrons for the S–S bond, we arrange the remaining 12 electrons as three lone pairs on each sulfur, giving each S atom an octet of electrons:

-

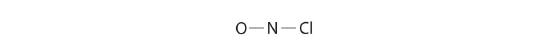

Because nitrogen is less electronegative than oxygen or chlorine, it is the central atom. The N atom (group 15) has 5 valence electrons, the O atom (group 16) has 6 valence electrons, and the Cl atom (group 17) has 7 valence electrons, giving a total of 18 valence electrons. Placing one bonding pair of electrons between each pair of bonded atoms uses 4 electrons and gives the following:

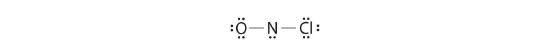

Adding three lone pairs each to oxygen and to chlorine uses 12 more electrons, leaving 2 electrons to place as a lone pair on nitrogen:

-

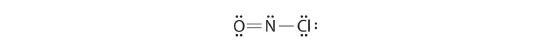

Because this Lewis structure has only 6 electrons around the central nitrogen, a lone pair of electrons on a terminal atom must be used to form a bonding pair. We could use a lone pair on either O or Cl. Because we have seen many structures in which O forms a double bond but none with a double bond to Cl, it is reasonable to select a lone pair from O to give the following:

All atoms now have octet configurations. This is the Lewis electron structure of nitrosyl chloride, a highly corrosive, reddish-orange gas.

Formal Charges

It is sometimes possible to write more than one Lewis structure for a substance that does not violate the octet rule, as we saw for CH2O, but not every Lewis structure may be equally reasonable. In these situations, we can choose the most stable Lewis structure by considering the formal charge on the atoms, which is the difference between the number of valence electrons in the free atom and the number assigned to it in the Lewis electron structure. The formal charge is a way of computing the charge distribution within a Lewis structure; the sum of the formal charges on the atoms within a molecule or an ion must equal the overall charge on the molecule or ion. A formal charge does not represent a true charge on an atom in a covalent bond but is simply used to predict the most likely structure when a compound has more than one valid Lewis structure.

To calculate formal charges, we assign electrons in the molecule to individual atoms according to these rules:

- Nonbonding electrons are assigned to the atom on which they are located.

- Bonding electrons are divided equally between the bonded atoms.

For each atom, we then compute a formal charge:

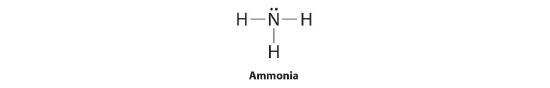

To illustrate this method, let’s calculate the formal charge on the atoms in ammonia (NH3) whose Lewis electron structure is as follows:

A neutral nitrogen atom has five valence electrons (it is in group 15). From its Lewis electron structure, the nitrogen atom in ammonia has one lone pair and shares three bonding pairs with hydrogen atoms, so nitrogen itself is assigned a total of five electrons [2 nonbonding e− + (6 bonding e−/2)]. Substituting into Equation 5.3.1, we obtain

A neutral hydrogen atom has one valence electron. Each hydrogen atom in the molecule shares one pair of bonding electrons and is therefore assigned one electron [0 nonbonding e− + (2 bonding e−/2)]. Using Equation 4.4.1 to calculate the formal charge on hydrogen, we obtain

The hydrogen atoms in ammonia have the same number of electrons as neutral hydrogen atoms, and so their formal charge is also zero. Adding together the formal charges should give us the overall charge on the molecule or ion. In this example, the nitrogen and each hydrogen has a formal charge of zero. When summed the overall charge is zero, which is consistent with the overall charge on the NH3 molecule.

Typically, the structure with the most charges on the atoms closest to zero is the more stable Lewis structure. In cases where there are positive or negative formal charges on various atoms, stable structures generally have negative formal charges on the more electronegative atoms and positive formal charges on the less electronegative atoms. The next example further demonstrates how to calculate formal charges.

Example

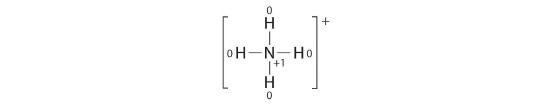

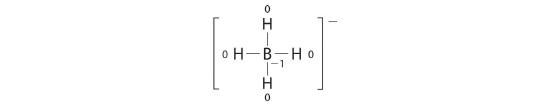

Calculate the formal charges on each atom in the NH4+ ion.

Given: chemical species

Asked for: formal charges

Strategy:

Identify the number of valence electrons in each atom in the NH4+ ion. Use the Lewis electron structure of NH4+ to identify the number of bonding and nonbonding electrons associated with each atom and then use Equation 4.4.1 to calculate the formal charge on each atom.

Solution:

The Lewis electron structure for the NH4+ ion is as follows:

The nitrogen atom shares four bonding pairs of electrons, and a neutral nitrogen atom has five valence electrons. Using Equation 4.4.1, the formal charge on the nitrogen atom is therefore

Each hydrogen atom in has one bonding pair. The formal charge on each hydrogen atom is therefore

The formal charges on the atoms in the NH4+ ion are thus

Adding together the formal charges on the atoms should give us the total charge on the molecule or ion. In this case, the sum of the formal charges is 0 + 1 + 0 + 0 + 0 = +1.

Using Formal Charges to Distinguish between Lewis Structures

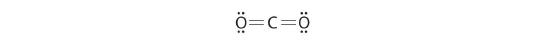

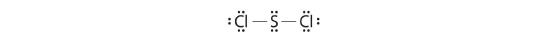

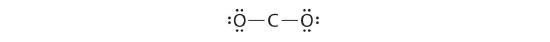

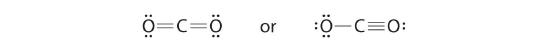

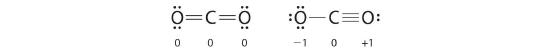

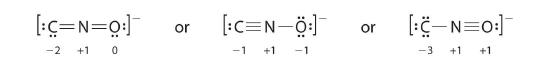

As an example of how formal charges can be used to determine the most stable Lewis structure for a substance, we can compare two possible structures for CO2. Both structures conform to the rules for Lewis electron structures.

2. C has 4 valence electrons and each O has 6 valence electrons, for a total of 16 valence electrons.

3. Placing one electron pair between the C and each O gives O–C–O, with 12 electrons left over.

4. Dividing the remaining electrons between the O atoms gives three lone pairs on each atom:

This structure has an octet of electrons around each O atom but only 4 electrons around the C atom.

5. No electrons are left for the central atom.

6. To give the carbon atom an octet of electrons, we can convert two of the lone pairs on the oxygen atoms to bonding electron pairs. There are, however, two ways to do this. We can either take one electron pair from each oxygen to form a symmetrical structure or take both electron pairs from a single oxygen atom to give an asymmetrical structure:

Both Lewis electron structures give all three atoms an octet. How do we decide between these two possibilities? The formal charges for the two Lewis electron structures of CO2 are as follows:

Both Lewis structures have a net formal charge of zero, but the structure on the right has a +1 charge on the more electronegative atom (O). Thus the symmetrical Lewis structure on the left is predicted to be more stable, and it is, in fact, the structure observed experimentally. Remember, though, that formal charges do not represent the actual charges on atoms in a molecule or ion. They are used simply as a bookkeeping method for predicting the most stable Lewis structure for a compound.![]()

Note

The Lewis structure with the set of formal charges closest to zero is usually the most stable.

Example

The thiocyanate ion (SCN−), which is used in printing and as a corrosion inhibitor against acidic gases, has at least two possible Lewis electron structures. Draw two possible structures, assign formal charges on all atoms in both, and decide which is the preferred arrangement of electrons.

Given: chemical species

Asked for: Lewis electron structures, formal charges, and preferred arrangement

Strategy:

A Use the step-by-step procedure to write two plausible Lewis electron structures for SCN−.

B Calculate the formal charge on each atom using Equation 4.4.1.

C Predict which structure is preferred based on the formal charge on each atom and its electronegativity relative to the other atoms present.

Solution:

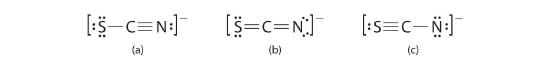

A Possible Lewis structures for the SCN− ion are as follows:

B We must calculate the formal charges on each atom to identify the more stable structure. If we begin with carbon, we notice that the carbon atom in each of these structures shares four bonding pairs, the number of bonds typical for carbon, so it has a formal charge of zero. Continuing with sulfur, we observe that in (a) the sulfur atom shares one bonding pair and has three lone pairs and has a total of six valence electrons. The formal charge on the sulfur atom is therefore

C Which structure is preferred? Structure (b) is preferred because the negative charge is on the more electronegative atom (N), and it has lower formal charges on each atom as compared to structure (c): 0, −1 versus +1, −2.

Drawing isomers of Lewis Structures

Contributors

- Anonymous

Layne Morsch (University of Illinois Springfield)