3: Diels-Alder Reaction

- Page ID

- 22895

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Basics

Discovered by Otto Paul Hermann Diels and Kurt Alder in 1928; awarded the Nobel prize in chemistry in 1950.

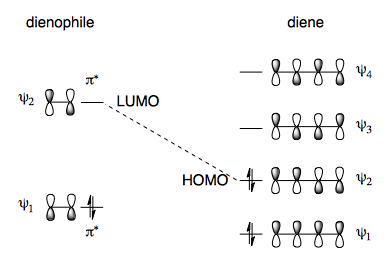

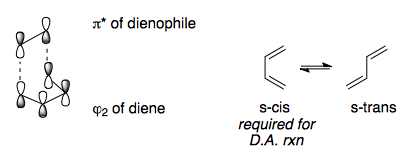

The LUMO of the dienophile reacts with the HOMO of the diene in a [4+2] cycloaddition. For more information, see Z/N p 421-432.

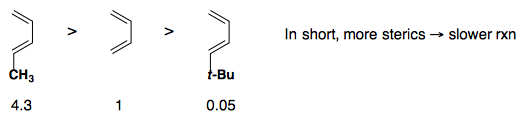

Steric Effects

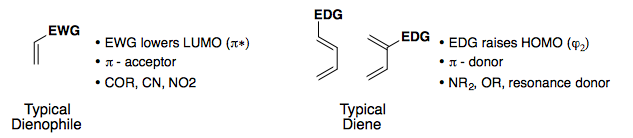

Electronic Effects

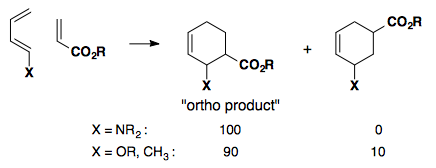

Regioselectivity

Electron-rich dienes paired with electron-poor dienophiles result in high selectivity for the "ortho products."

One way to think about pairing the diene/dienophile is to consider resonance structures in which the alkenes have charge separation. Note: there is no actual charge separation, but it can help explain the regiochemistry.

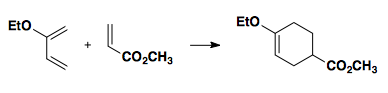

For practice, convince yourself the the following reaction yields the product shown.

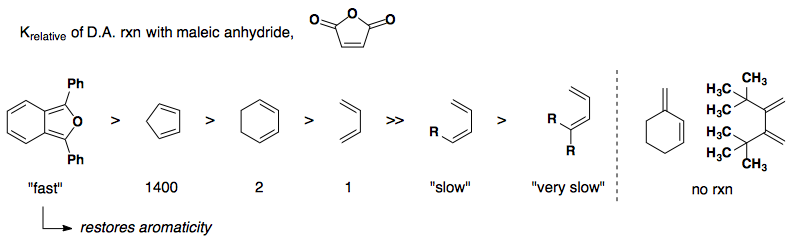

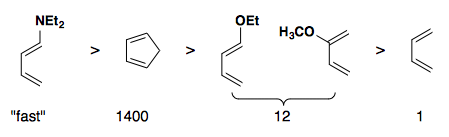

Rate of reactivity: diene

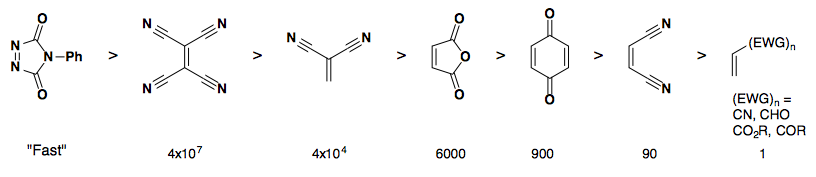

Rate of reactivity: dienophile

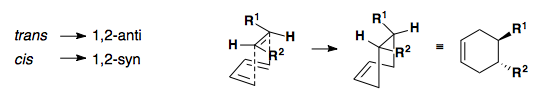

Stereochemistry

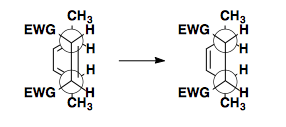

The stereochemistry of the diene and dienophile is translated to the cyclohexene product. In short, the geometry of the alkenes (cis/trans) is directly related to the syn/anti relationship observed in the product.

Dienophile

Diene

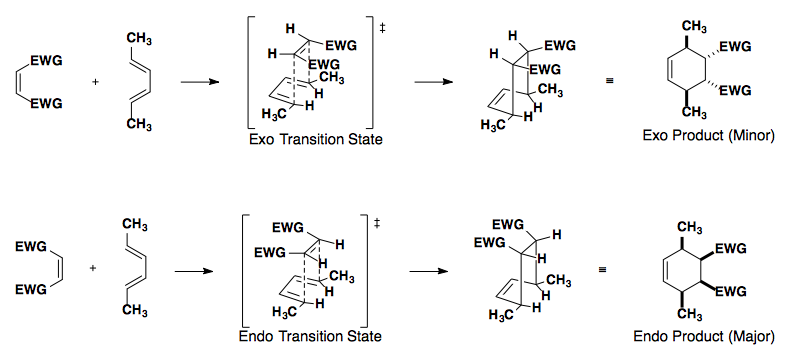

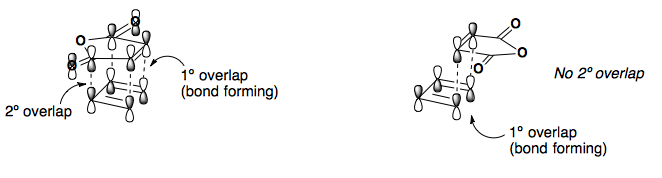

In this example, the diene can react with the dienophile in two ways: the exo or endo approach.

Endo approach is preferred due to the secondary overlap of pi-orbitals.

Another way to look at the transition state is to draw a double Newman projection.

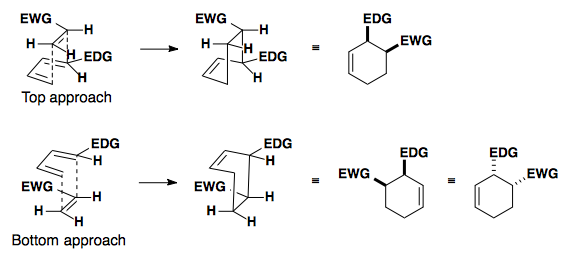

Top/Bottom Approach

If the dienophile can approach the diene from the top or bottom face, enantiomers are formed.

High Endo Selectivity

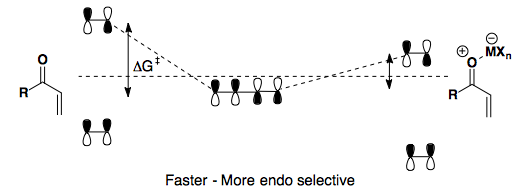

Controlling the Diels-Alder reaction to select for the endo product relies on changing the HOMO and/or LUMO of the system.

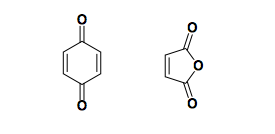

Cyclic dienophiles

Common examples are quinone and maleic anhydride.

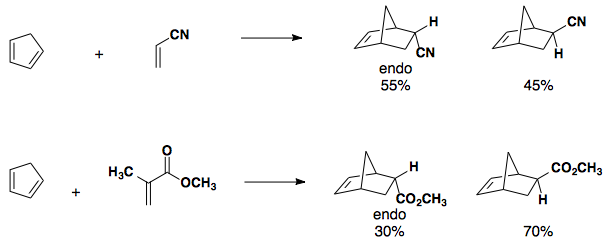

Electron-neutral cyclopentadiene paired with electron-poor dienophiles gives a mix of endo and exo products.

Electron-rich Dienes

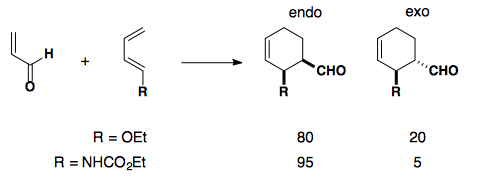

If an electron-rich diene is paired with an electron-poor dieneophile, the reaction undergoes cycloaddition with excellent endo selectivity. Adding electron density into the diene's molecular orbitals raises the HOMO.

Electron-poor Dienophiles

Adding a Lewis acid further depletes the dienophile of its electron density, thereby lowering the LUMO.

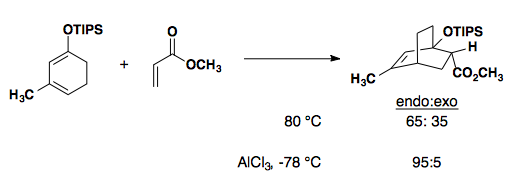

Here, we see an electron-rich, cyclic diene paired with an electron-poor dienophile. Heating the reaction gives poor endo/exo selectivity. However, upon addition of a Lewis acid (AlCl3), the reaction can proceed at low temperature and th endo product is highly favored.

Intramolecular Diels-Alder: the rules are breakable

Two types of connectivity for intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions exist:

- Type I - a linear connection where the dienophile is attached (at length) at position 1 of the diene; or

- Type II - a branched connection where the dienophile is attached (at length) at position 2 of the diene.

Type I results in a fused bicyclic ring system. Type II results in a bridged bicyclic ring system.

Intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions can be found in a number of total syntheses (Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1668-1698). For an example of a Type II Diels-Alder reaction in practice, see Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 820-849.

Asymmetric Diels-Alder

Substrates with bulky substituents will affect the diastereoselectivity of a Diels-Alder reaction by limiting the approach of the diene/dienophile pair. Here, we see the preferred endo product that minimizes steric interactions with the phenyl substituent (Synthesis 2002, 2457-2463).

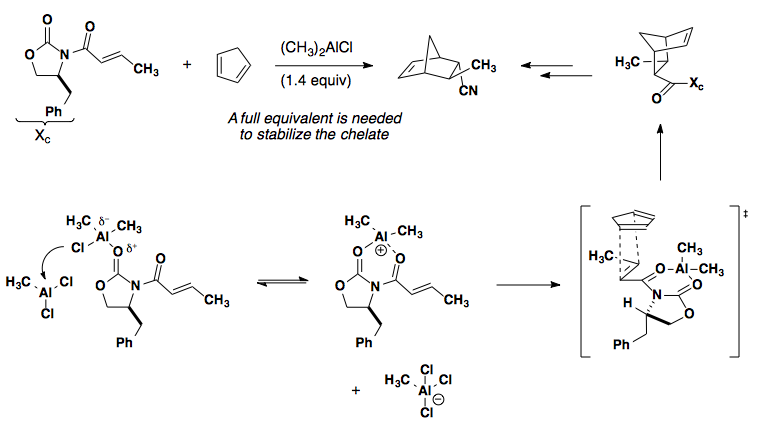

Chiral Auxiliaries

Incorporating a chiral auxiliary and Lewis acid can lead to facial control of the cycloaddition by blocking one face of the dienophile. Examples of oxazolidinones with R2AlCl can be found here: J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 1238-1256 (shown below); J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 1186-1194 (IMDA, Type I); J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 4261-4263 (IMDA, Type I); Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1650-1667 (review); CAC '99 1177.

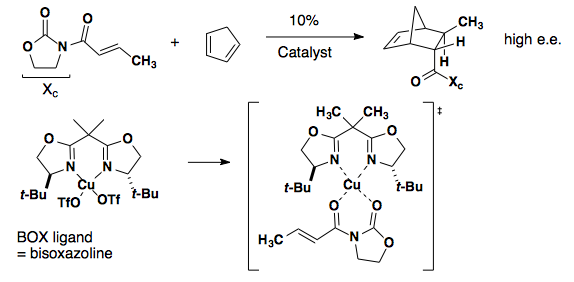

Chiral Catalysis

Chiral catalysts have also been shown to control the enantioselectivity of a Diels-Alder reaction.

Oxazolidinone/oxazoline

The achiral oxazolidinone below relies on a chiral BOX ligand and coordination of a copper catalyst (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 6460-6461).

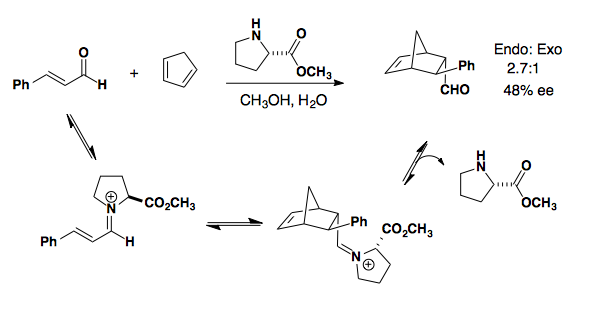

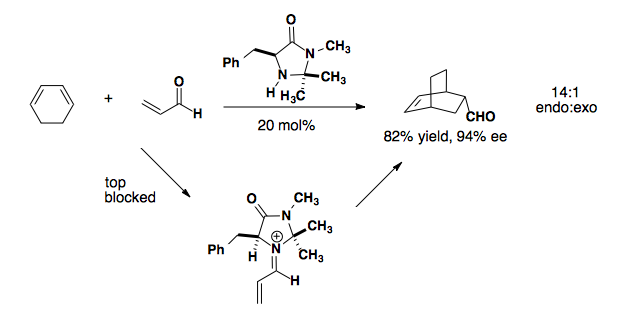

Iminium Catalyzed

Iminium formation blocks one face of the dienophile so that approach of the diene results in endo selectivity and good to high enantioselectivity (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4243-4244).

Proline derived

Imidazolidinone derived

Application to a Total Synthesis of dl-Estrone

A cobalt-mediated alkyne cyclization undergoes a ring closing and re-opening to set up a Type I Diels-Alder reaction (J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980, 102, 5253-5261).

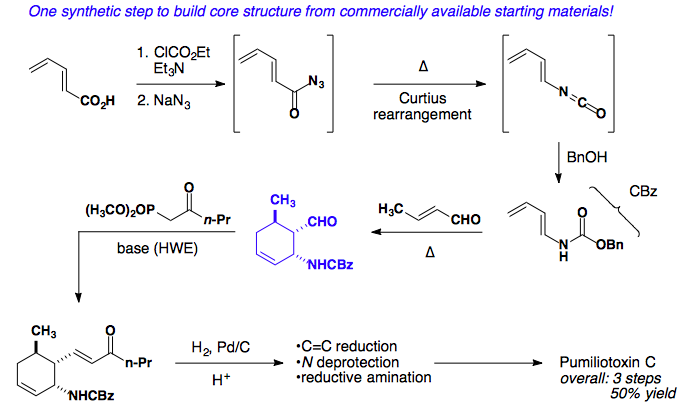

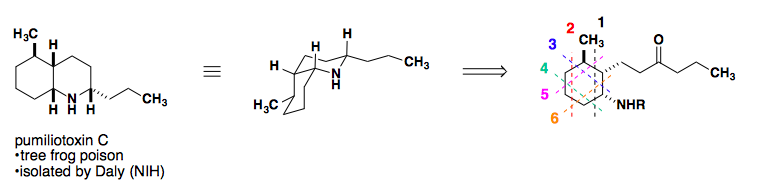

Application to a Total Synthesis of dl-Pumiliotoxin C

L. E. Overman published a stereospecific synthesis of pumiliotoxin in 1977 as a racemic mixture. The following year, his group published a second iteration of the same core, but with a much shorter overall synthesis (Tetrahedron Lett. 1977, 18, 1253-1256; J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978, 100, 5179-5185).

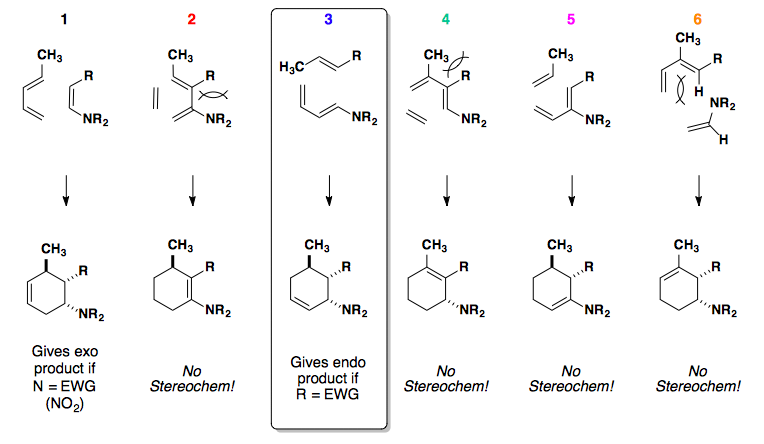

Retrosynthetic analysis of the cis-decalin core suggests six possible disconnections.

Considering all possible diene/dienophile pairs, disconnection #3 displays all favorable attributes: electron-rich diene, electron-poor dienophile, and endo selectivity to provide the desired stereochemistry of the product.

The forward synthesis showcases a Curtius rearrangement to build the requisite carbamate protected diene. Susequent addition of crotonaldehyde and heat results in the cyclohexene core, which can undergo a Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction and reduction to give an advanced intermediate. Deproection and reductive amination provides the natural product in 3 steps and 50% overall yield.