2.2.2: Anatomy of a MOL file

- Page ID

- 83691

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

|

UALR 4399/5399: ChemInformatics |

|

Most connection table formats contain one or more of the following:

- A list of atoms, specifying the elemental identity of each atom

- A list of bonds, specifying the atoms that it connects and the bond multiplicity (single, double, triple)

- 2D or 3D spatial coordinates for each atom (sometimes measured, sometimes calculated; often, it’s not clear which)

- Counts of the number of atoms and bonds in the molecule

- Attributes associated with atoms or bonds (e.g. R/S configuration of a stereocenter; dashed/wedged bond

- Attributes associated with an entire structure (e.g. net charge)

The MOL file, a widely-used chemical structure file format, contains all of these.

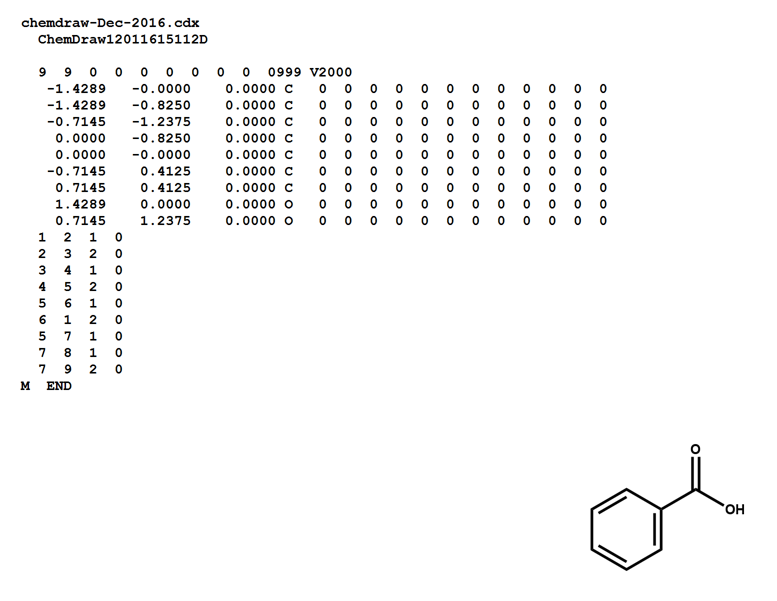

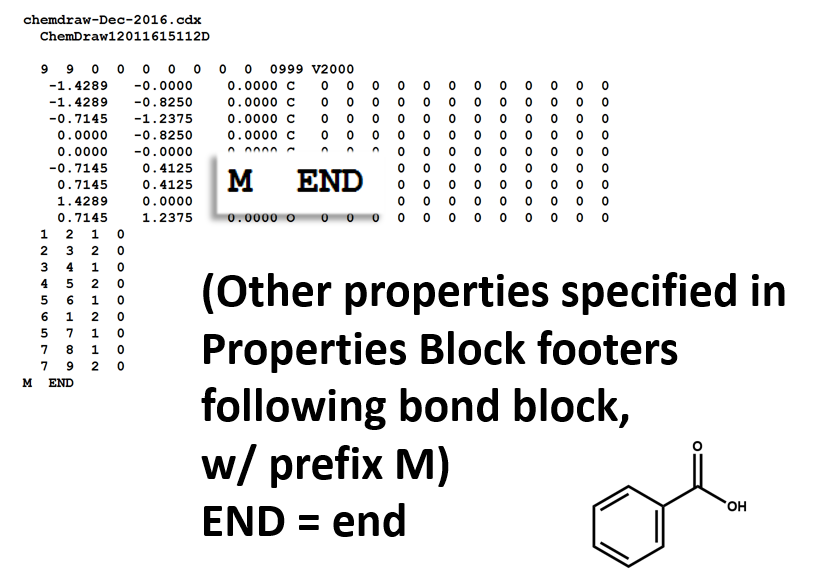

Here is a MOL file for benzoic acid, generated by ChemDraw, which provides options to save or to copy sketches in this file format.

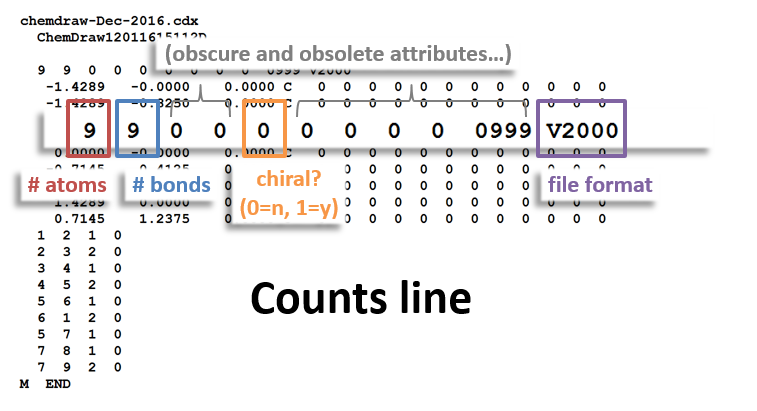

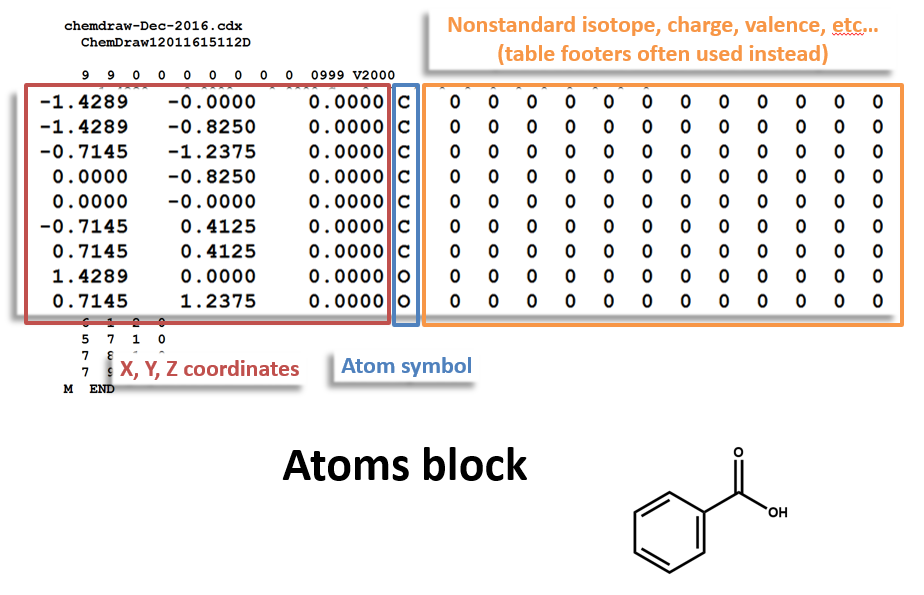

The following figures illustrate the anatomy of a MOL file (MOL v2000, to be specific): the counts line, the atoms block, the bonds block, and the properties block.

Counts Block:

Atoms Block:

Bonds Block:

Properties Block

Note that benzoic acid has nine atoms and nine bonds, not counting hydrogen. If all explicit hydrogen was included in this connection table, there would be six more entries in the atoms and bonds blocks, and the counts line would show fifteen atoms and fifteen bonds.

Multiple molecules

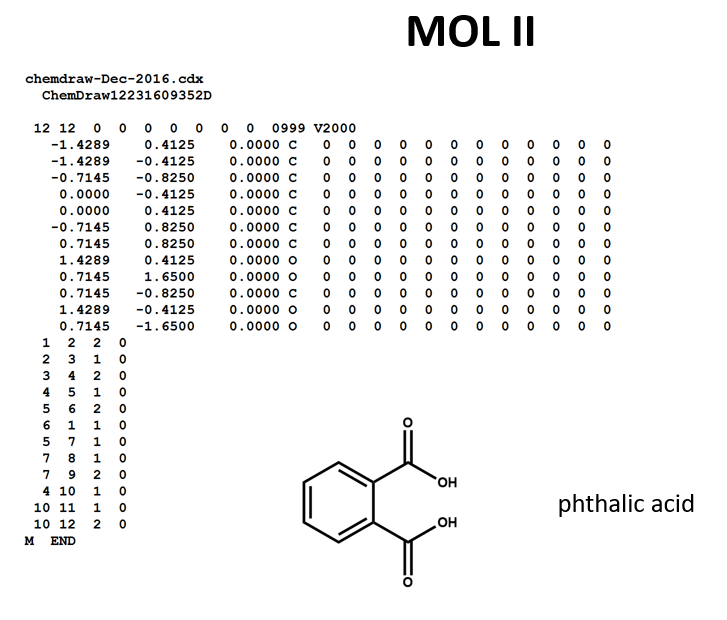

A connection table can represent multiple distinct compounds. Take a look at MOL II, phthalic acid.

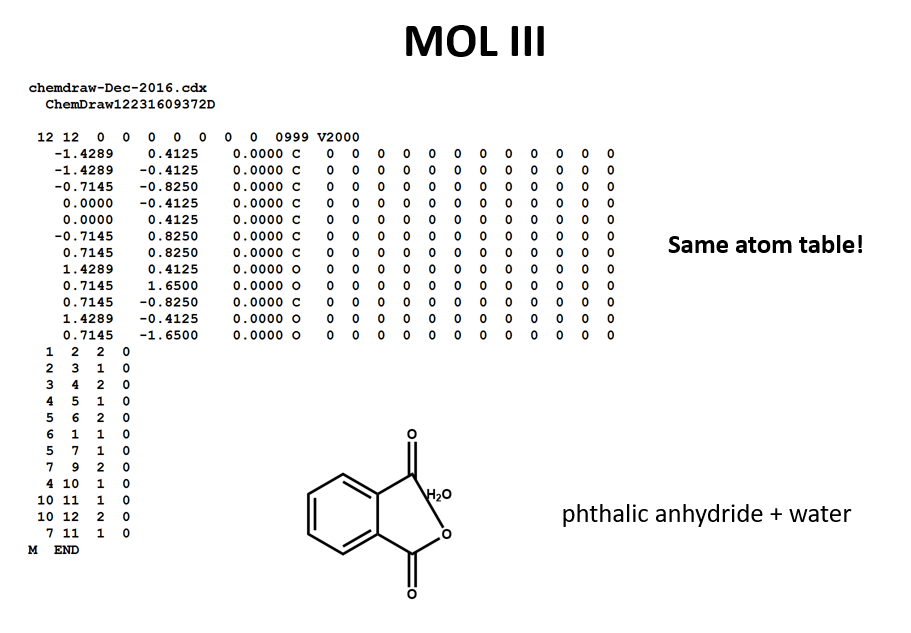

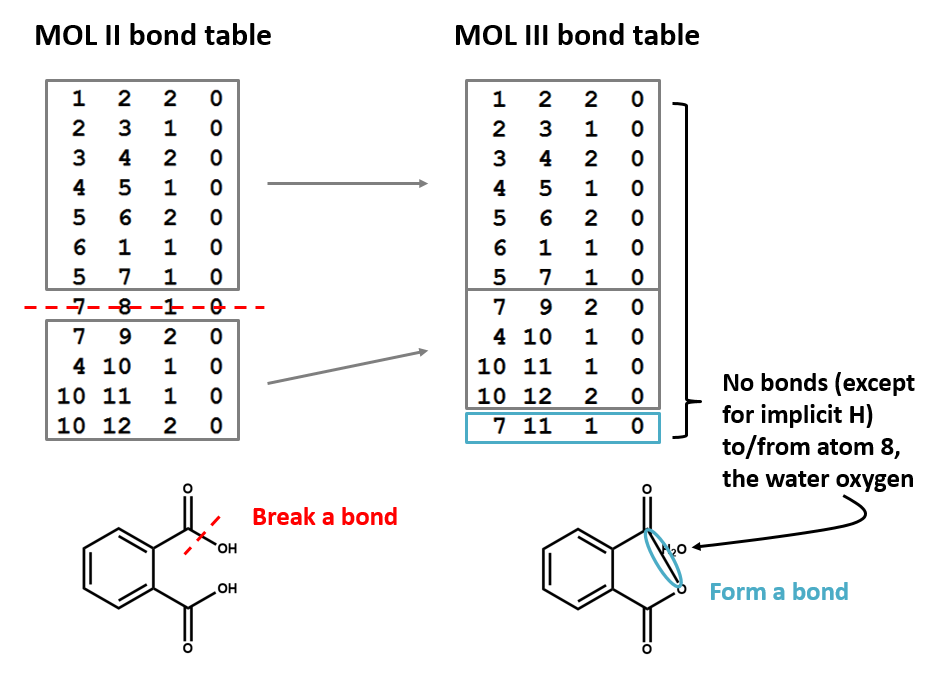

We can represent the stoichiometrically equivalent phthalic anhydride plus water by keeping the same atom block and changing a couple of entries in the bonds block. Now, we have one connection table (MOL III) representing two molecules. (Connection tables can also be used in representing reactions. For more on this, see online documentation on MOL and related file formats.)

Let's compare the bond tables of the above two files:

Tricky Features

Working with connection tables can become tricky when it comes to features of chemical identity that are not directly represented as a static collection of atoms and covalent bonds, such as:

- Aromaticity and delocalization

- Tautomerism

- Coordination

Sometimes these phenomena are not (or even cannot be) represented in the connection table at all. Other times, different file formats (or different users of the same file format) will adopt different conventions for indicating them. This can make things tricky for those who want to manipulate chemical structure data across the tens of millions of known chemical compounds (and the limitless space of possible compounds). However, it also means that there are ample opportunities for developing clever cheminformatic solutions to the limitations of connection tables.

Few of these issues are likely to be solved completely. Think of the following examples, and the exercises that follow, as training in the sort of questions that you would be prudent to ask when it comes to working with digital data about chemical structures.

Aromaticity

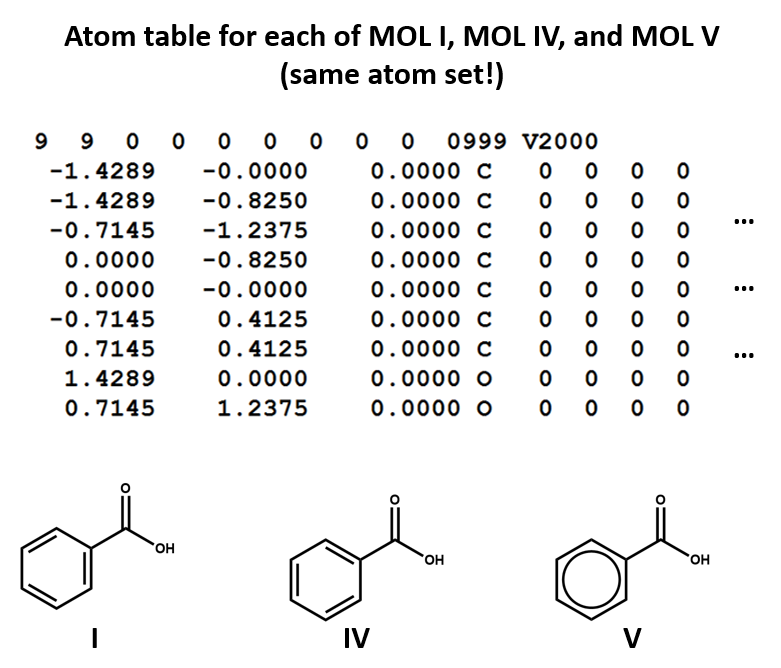

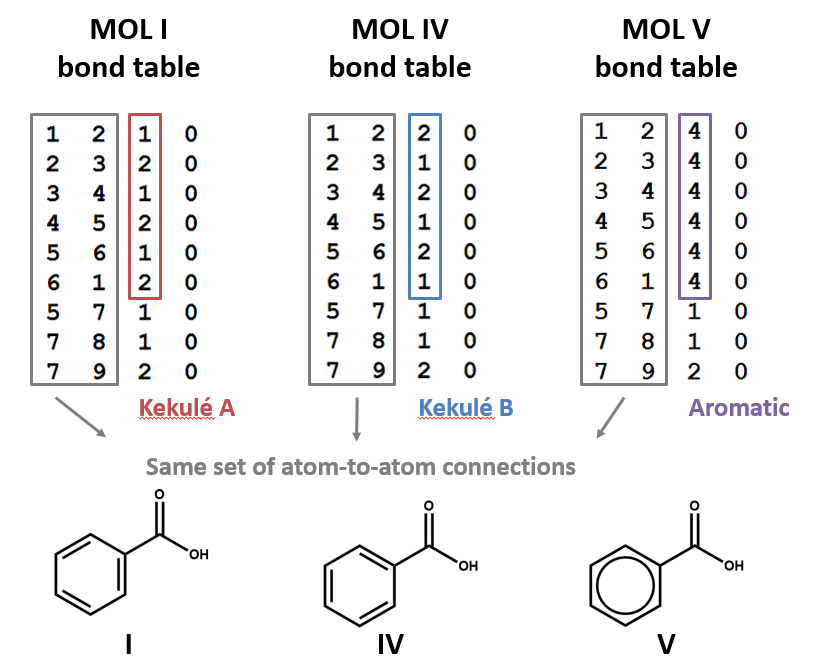

Structural formulas I, IV, and V all representing the same molecule: benzoic acid. However, remember: connection tables are typically correspond to structural formulas on an atom-by-atom, bond-by-bond level, not on a holistic level. Since these are three different patterns of atoms and bond, they correspond to three different MOL files. Each of the two Kekulé structures for the benzene ring shows up as a different set of single and double bonds (MOL I, MOL IV).

The MOL file format uses the number 4 to indicate bonds that are explicitly labeled as aromatic (MOL V). This has the advantage of differentiating aromatic bonds from single and double bonds without requiring the chemist to write a script to identify and label the alternating single and double bonds of a Kekulé structure. However, some software may not be built to handle this convention. (You might even run into cases in which it’s interpreted as a quadruple bond!)

Conjugate acids and bases

Two structural formulas may represent the same compound in different conditions. (E.g. conjugate acids/bases.) Again – keep in mind that, even though these structural formulas may refer to the same compound, they will be represented by different connection tables. You may need to choose one or the other of these connection tables / structural representations – or both – depending on your aims and the conventions of the database that you’re using. (V, VI)

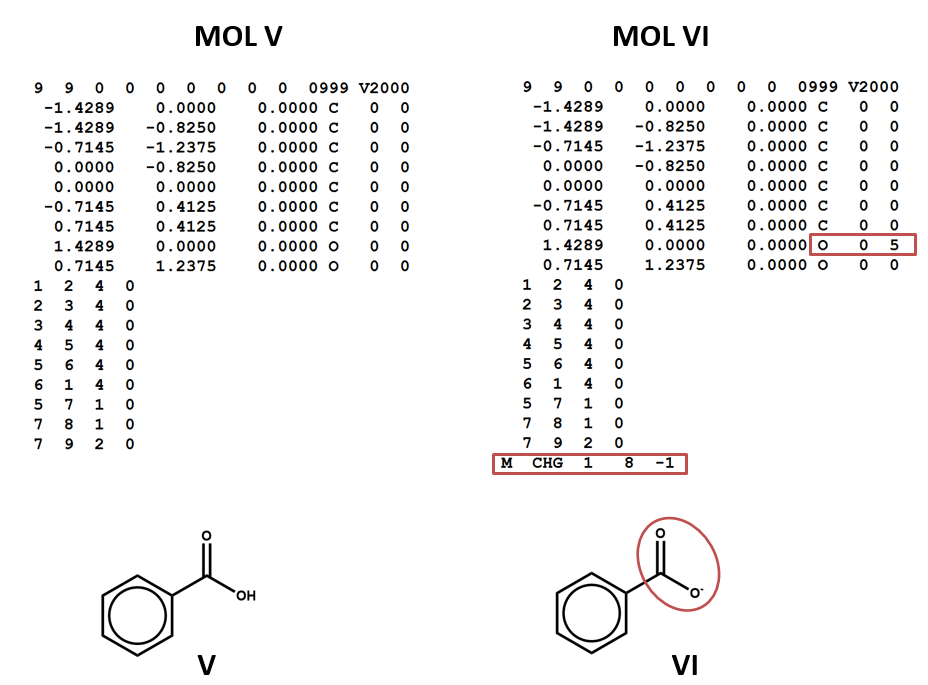

Resonance

Run-of-the mill delocalization presents some of the same problems as aromaticity, but there is no conventional label for (non-aromatic) delocalized electrons, such as the delocalized negative charge and pi system in benzoate (VII and VIII). The connection tables will simply represent one resonance structure or another.

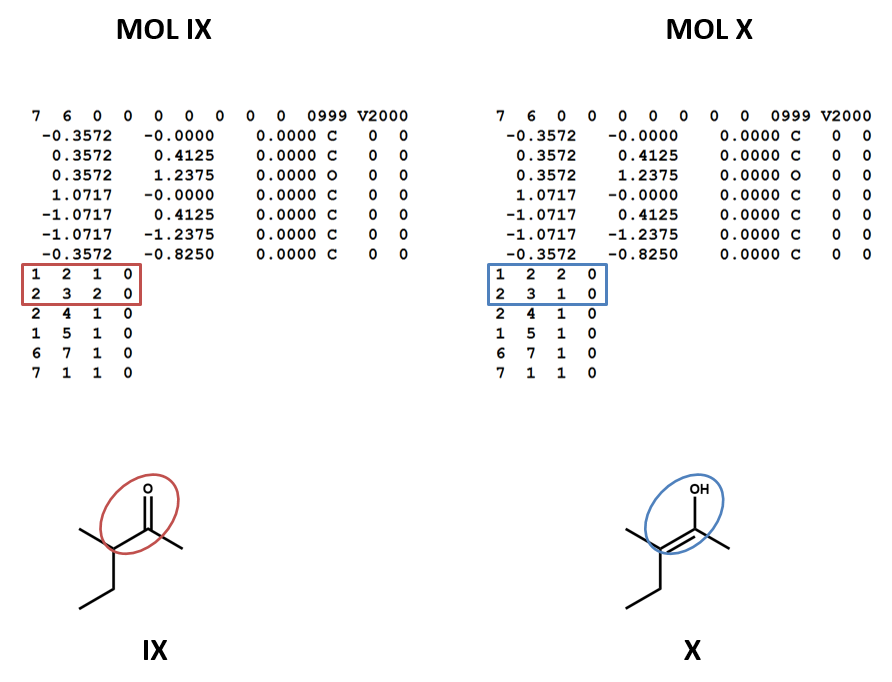

Tautomerism

Connection tables don’t link together tautomers in a straightforward way. You may need to work with multiple connection tables to account for different tautomers or to make sure that you have the most appropriate one for your purposes (IX, X).

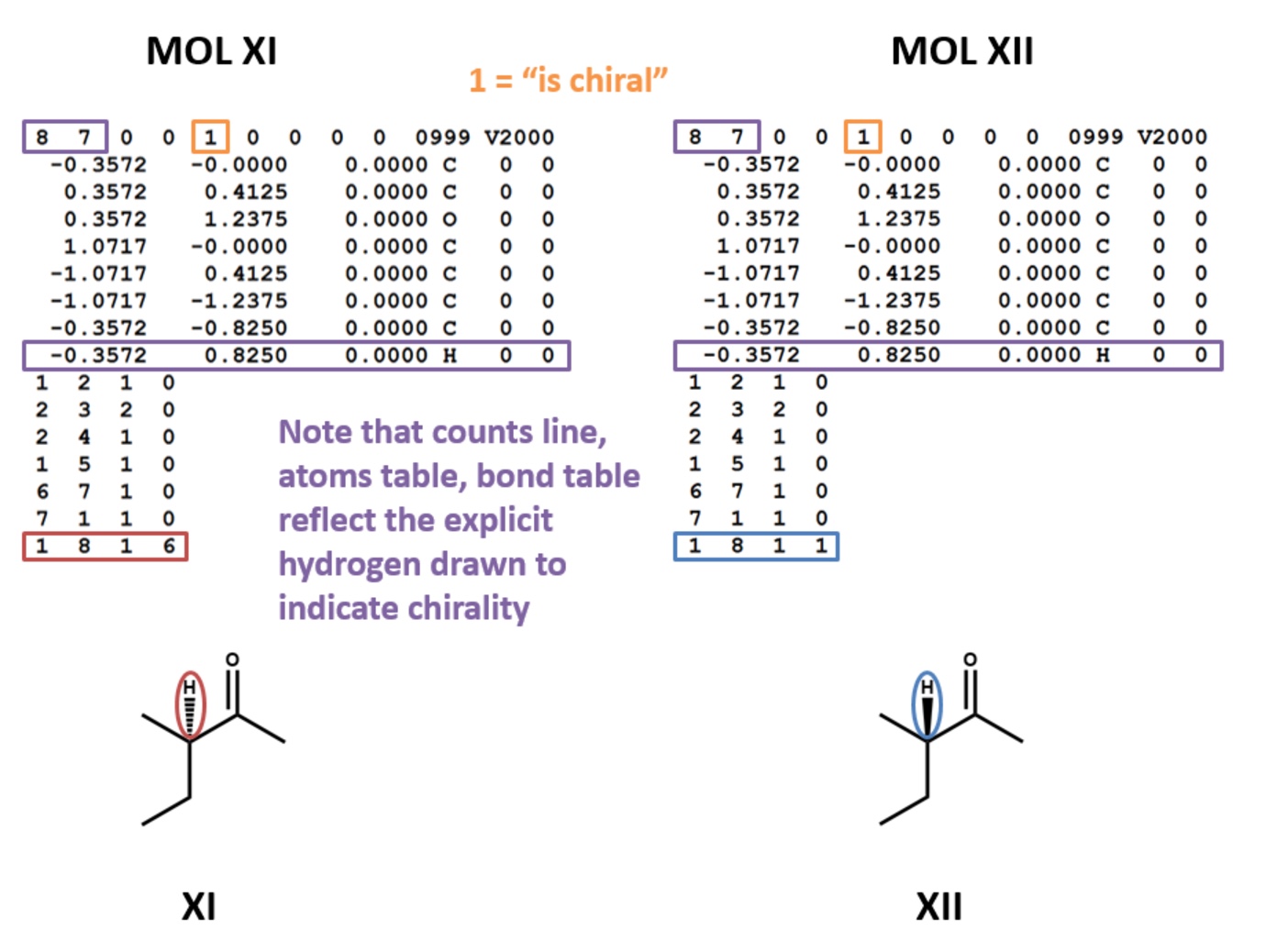

Chirality

MOL files do indicate chirality. However, they can do so in two ways. A “1” or “6” in the fourth field of the bonds table indicates wedged and dashed bonds, respectively. A “1” or “2” in the stereochemistry field of the atom table represents the chirality of a stereocenter. (To make things even more complicated, software may account for the chirality of a stereocenter atom when generating a MOL file but ignore it when rendering a MOL file!) (XI, XII)

Hack-a-Mol

Here’s a website at St. Olaf College where you can play with the relationship between 2D structures, 3D renderings, identifiers, and connection tables, courtesy of the cheminformatician Bob Hanson. There’s a link on the page to a document explaining “How it Works” (also linked here). As this course proceeds you will learn how we communicate with the NCI resolver and PubChem, and many of the fundamental features behind this application.

We have also embedded Hack-a-Mol below, and when doing your assignments you may want to open in a new window.

Hack-a-MolThis page is designed especially for students of cheminformatics who are just starting to learn about how chemical structures are represented digitally.With this page you can draw a structure in 2D, compare that with its 3D structure, and also see its structural data in a variety of formats. You can also enter a chemical identifier -- a chemical name, a SMILES string, or a Chemical Abstracts Registry Number, for instance -- in the box under the JSmol window. If you hack the structural data (carefully!) and then press ENTER, the 2D and 3D structures will update. You can also drag-drop a structure file into the JSmol window or copy/paste it into the textarea. How It Works Author: Bob Hanson |

|

labels console info clear no info |

|

| InChI: InChIKey: SMILES: |

|||

Modify the data and press ENTER to see changes above. UNDO Modify the data and press ENTER to see changes above. UNDO |

|||

Let’s take another look at benzoic acid. Clear the 2D sketch window using the white box button at the top, second from the left, and then draw benzoic acid. Click the right arrow button. That should render a 3D structure in the window to the right and generate a MOL file in the text window below. (For details on how where this data comes from, see “2D to 3D” and “3D to structure data” sections in “How it Works.”)

Now, take a look at the MOL file in the text window. You will note that, as a default, Hack-a-Mol includes explicit H in the MOL files it generates. (See discussion of explicit and implicit H earlier in this module for more information.)

Identify the atoms and bonds that make up the ring. (These will vary depending on the way that you drew the molecule – the 2D sketch application numbers atoms and bonds in the order that they are drawn.) Remember, the first two columns in each bond table entry refer to rows in the atom table, and the third column gives the bond type (1=single, 2=double, etc.) connecting these two atoms. (You can check yourself by hovering over atoms in the 3D window or clicking the “labels” link above this window.)

Once you have identified the six ring bonds in the MOL file, manually adjust them to generate the other Kekulé structure of the ring. (That is, switch the 1’s for 2’s and the 2’s for 1’s in the bond type fields (third column) of the bond table entries for the six ring bonds.) With the cursor still in the text window, press enter. This should generate the other Kekulé structure for benzoic acid in both the 3D and 2D windows.

Just for kicks, let’s generate a nonsense structure. Change all of the ring bonds to double bonds, and press enter. You should now have a chemically-offensive structure involving a cyclohexahexene ring with six positively charged carbon atoms violating valence rules. There’s a lesson here – software won’t tell you that your structure data is chemically nonsensical unless it is programmed to do so.

Revert to benzoic acid, either by changing the bonds back manually or just by clearing the 2D sketch window, re-drawing, and clicking the right arrow button again.

Now, let’s stick a chlorine atom onto the benzene ring. Using the atom and bond tables, locate the atom table entry for a ring hydrogen ortho, meta, or para to the carboxyl group (your pick!). Change the atom symbol in this atom table entry from H to Cl, and press enter. You should now have the chlorobenzoic acid isomer of your choice in both 3D and 2D windows.

One more exercise: let’s make our benzoic acid into pyridine-3-carboxylic acid – that is, benzoic acid with N in place of one of the ring carbons meta to the carboxylic group. This is the compound better known as niacin (vitamin B3).

(Tangential fun fact: niacin, discovered as an acidic reaction product of nicotine, was originally named nicotinic acid. In the 1930s, it was found to be the essential nutrient that prevented pellagra, a devastating disorder widely prevalent in the American South in the early twentieth century. Public health officials promoted enriching flour with nicotinic acid, and the epidemic of pellagra began to disappear. However, physicians and scientists worried that the name “nicotinic acid” gave the impression that they were curing mass disease by putting tobacco into bread. A National Research Council committee decided to change the name of the substance to niacin, short for nicotinic acid vitamin.)

Anyway: locate the entry for a ring carbon meta to the carboxyl group. (Hint: 1) use the atom and bond tables to identify the carbon atom bonded to the two oxygen atoms; 2) find the ring carbon bonded to that carboxyl carbon; 3) find a ring carbon two bonds away from that carboxyl-substituted ring carbon.) Change that carbon to N, and press enter.

Now we have the N atom in our ring, but you will notice that it’s positively charged. We didn’t change any of the explicit hydrogens, so the N atom remains protonated, like the C atom that it replaced. Let’s get rid of that hydrogen atom. Locate the entry for the N-H bond in the bond table and the entry for the corresponding H atom in the atom table, and delete both of them. Press enter.

Unless you were very lucky, you should now have a monstrous mess in the 3D window and nothing at all in the 2D window. Uh-oh. Go back to the MOL file window, press ctrl-Z twice to undo the deletion of those rows, and press enter. That will take you back to N-protonated niacin.

By deleting a row of the atom table, we renumbered all of the subsequent atom table entries. Since we didn’t change the atom references in the bond table, this broke all of the bonds to these renumbered atoms.

Once again, delete that N-H bond from the bond table and the entry for that H atom in the atom table. However, now fix the bond table references by **decreasing the atom number by 1** for all atoms below the row that you deleted. (That is, if the hydrogen that you deleted was the 13th atom table entry, change each 14 in the first two columns of the bond table to a 13, and change each 15 in the first two columns of the bond table to a 14.)

Hit enter. Ugh – your structure is probably screwed up **again**, even if you did all of this renumbering correctly. You may even have lost your ring, for some reason.

Take a look at the counts line of the MOL file – the row above the atom table, just below the file headers. The first two numbers in this line refer to the number of atoms and bonds in the molecule. Since we deleted an atom and a bond, we need to decrease each of these from 15 to 14. Do so, and then press enter again. You should now have niacin.

Whew. Thank goodness that connection table handling is so amenable to automation!

Play around some more with Hack-a-Mol. Take a look at the “How it Works” page – a lot of the notations, apps, and processes referred to on this page will be covered in subsequent weeks. You may find it useful to continue to come back to this page and play around with it as you move on in this course.

EXERCISE

1. Does Hack-A-Mol handle the number 4 for an aromatic bond? How can you tell? Can you create a chemically sound but non-aromatic structure using 4s in the bond field?

2. Perfluorinated octanoic acid (PFOA) is a surfactant that played a key role for a long time in the manufacture of fluorinated polymers including Teflon. Over the past decade, it has been the subject of significant public health concern and a whole bunch of litigation.

Pull PFOA into Hack-a-Mol by typing it into the text search box below the 3D window and clicking “search.”

2a. Edit the mole file to defluorinate PFOA, converting it into octanoic acid.

2b. Now make it into acetic acid. (It is possible to do this in a way that yields correct-looking 2D and 3D renderings without changing any XYZ coordinately, but you have to be ***very*** careful about how you delete and relabel atoms and bonds.)

FURTHER READING

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chemical_table_file

- CTFile Formats, June 2005, Elsevier/MDL, https://web.archive.org/web/20070630061308/http://www.mdl.com/downloads/public/ctfile/ctfile.pdf (Documentation for v2000 MOL file and related chemical table file formats.)

- Hack-a-Mol: https://chemapps.stolaf.edu/jmol/jsmol/hackamol.htm

- (Documentation: https://chemapps.stolaf.edu/jmol/docs/misc/hackamolworkings.pdf)

Contributors

Evan Hepler-Smith, Harvard

Leach McEwen, Cornell

Bob Hanson (Hack-a-mol)