3.5: Reactions of Epoxides- Ring-opening

- Page ID

- 469371

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Epoxide Ring-Opening by Alcoholysis

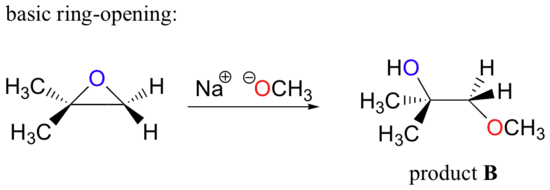

The ring-opening reactions of epoxides provide a nice overview of many of the concepts discussed earlier. Ring-opening reactions can proceed by either SN2 or SN1 mechanisms, depending on the nature of the epoxide and on the reaction conditions. If the epoxide is asymmetric, the structure of the product will vary according to which mechanism dominates. When an asymmetric epoxide undergoes alcoholysis in basic methanol, ring-opening occurs by an SN2 mechanism, and the less substituted carbon is the site of nucleophilic attack, leading to what we will refer to as product B:

Conversely, when solvolysis occurs in acidic methanol, the reaction occurs by a mechanism with substantial SN1 character, and the more substituted carbon is the site of attack. As a result, product A predominates.

These are both good examples of regioselective reactions. In a regioselective reaction, two (or more) different constitutional isomers are possible as products, but one is formed preferentially (or sometimes exclusively).

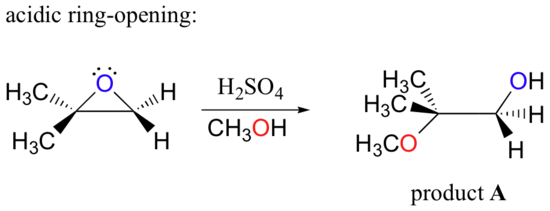

Basic Epoxide Ring-Opening by Alcoholysis

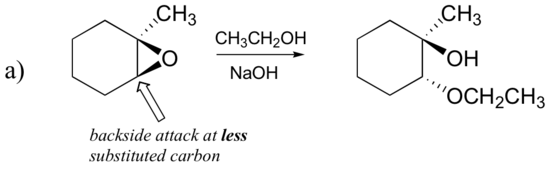

In the basic, SN2 reaction, the leaving group is an alkoxide anion, because there is no acid available to protonate the oxygen prior to ring opening. An alkoxide is a poor leaving group, and thus the ring is unlikely to open without a 'push' from the nucleophile.

The nucleophile itself is potent: a deprotonated, negatively charged methoxide ion. When a nucleophilic substitution reaction involves a poor leaving group and a powerful nucleophile, it is very likely to proceed by an SN2 mechanism.

There are two electrophilic carbons in the epoxide, but the best target for the nucleophile in an SN2 reaction is the carbon that is least hindered. This accounts for the observed regiochemical outcome. Like in other SN2 reactions, nucleophilic attack takes place from the backside, resulting in inversion at the electrophilic carbon.

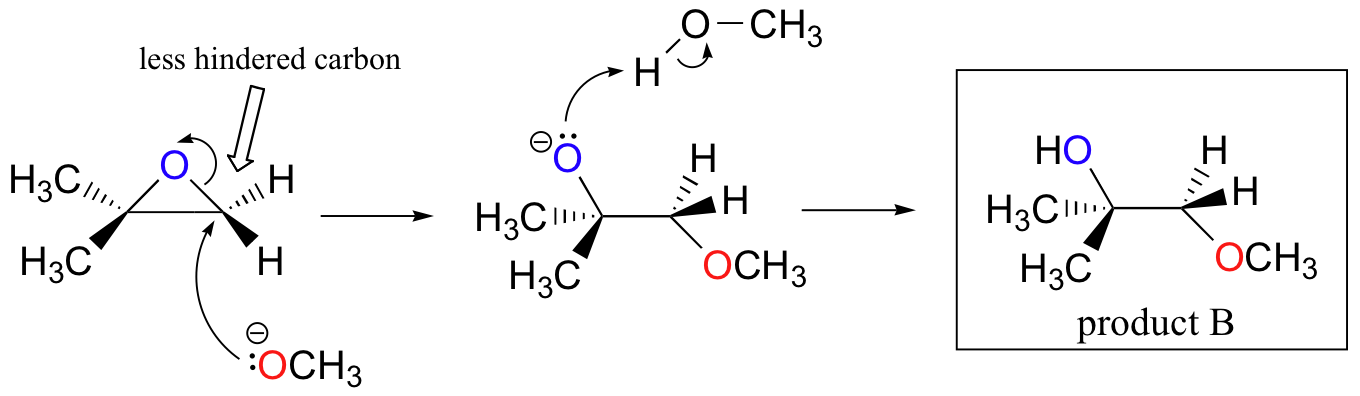

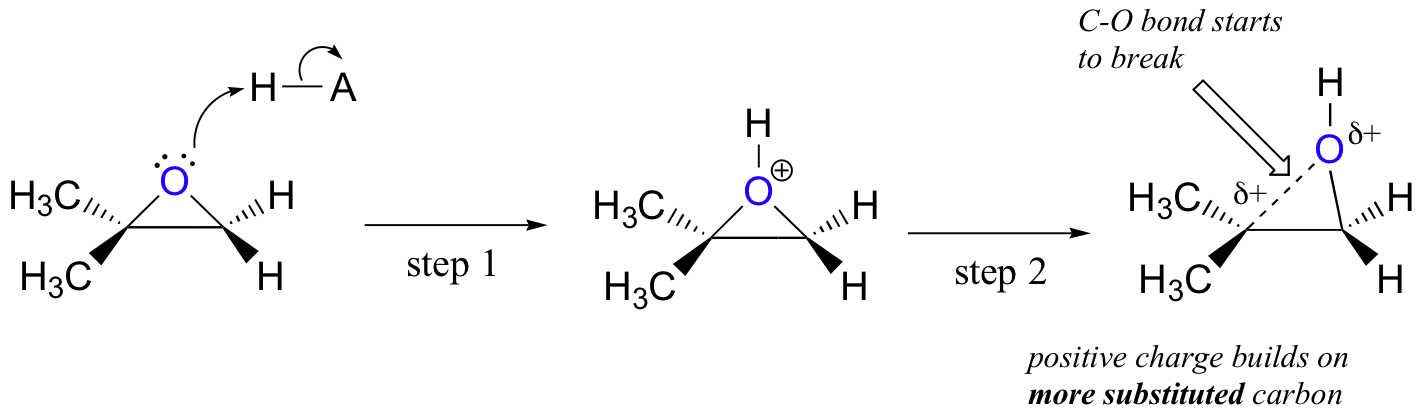

Acid-Catalyzed Epoxide Ring-Opening by Alcoholysis

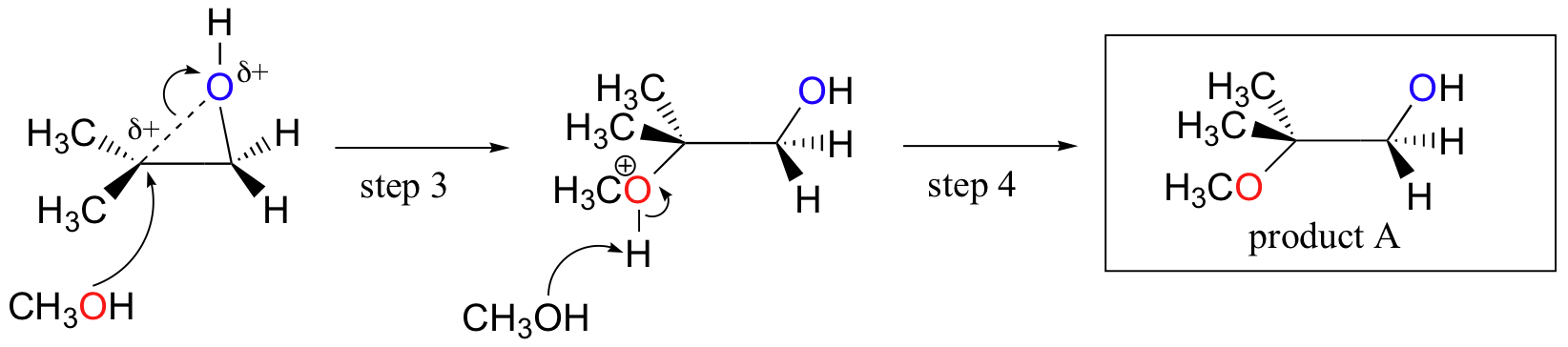

The best way to depict the acid-catalyzed epoxide ring-opening reaction is as a hybrid, or cross, between an SN2 and SN1 mechanism. First, the oxygen is protonated, creating a good leaving group (step 1 below). Then the carbon-oxygen bond begins to break (step 2) and positive charge begins to build up on the more substituted carbon. Recall that alkyl substituents can donate electron density through hyper conjugation and stabilize a positive charge on a carbon.

Unlike in an SN1 reaction, the nucleophile attacks the electrophilic carbon (step 3) before a complete carbocation intermediate has a chance to form.

Attack takes place preferentially from the backside (like in an SN2 reaction) because the carbon-oxygen bond is still to some degree in place, and the oxygen blocks attack from the front side. Notice, however, how the regiochemical outcome is different from the base-catalyzed reaction: in the acid-catalyzed process, the nucleophile attacks the more substituted carbon because it is this carbon that holds a greater degree of positive charge.

Predict the major product(s) of the ring opening reaction that occurs when the epoxide shown below is treated with:

- ethanol and a small amount of sodium hydroxide

- ethanol and a small amount of sulfuric acid

![Wedge-dash structure of 1-methyl-7-oxabicyclo[4.1.0]heptane](https://chem.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/5724/image129.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=100&height=75)

Hint: be sure to consider both regiochemistry and stereochemistry!

- Answer

-

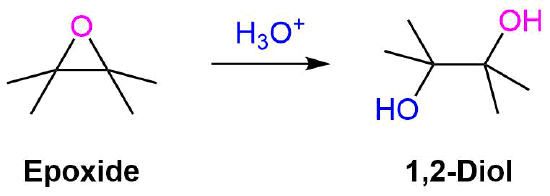

Epoxide Ring-Opening by Hydrolysis

Epoxides may be cleaved by hydrolysis to give trans-1,2-diols (1,2 diols are also called vicinal diols or vicinal glycols). The reaction can be preformed under acidic or basic conditions which will provide the same regioselectivity previously discussed.

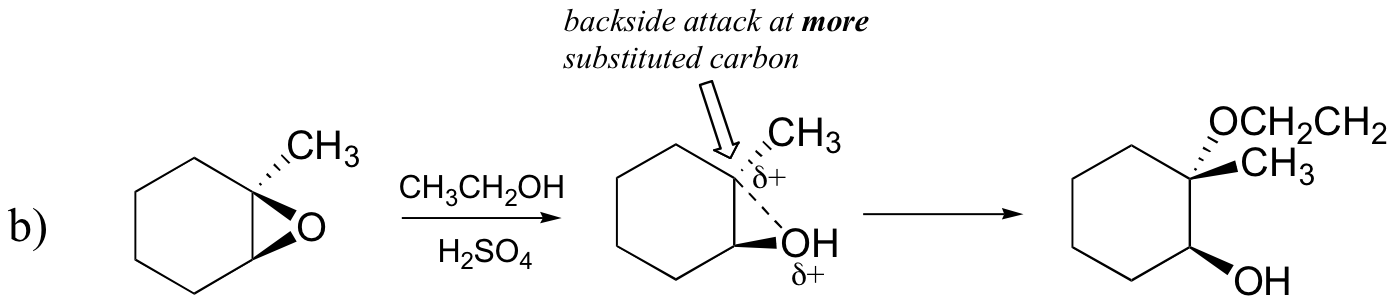

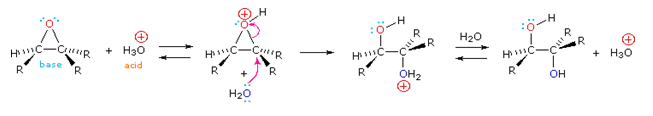

Acid Catalyzed Hydrolysis

Under aqueous acidic conditions the epoxide oxygen is protonated and is subsequently attacked by a nucleophilic water. After deprotonation to reform the acid catalyst a 1,2-diol product is formed. If the epoxide is asymmetric, the incoming water nucleophile will preferably attack the more substituted epoxide carbon. The epoxide ring is opened by an SN2 like mechanism so the two -OH groups will be trans to each other in the product.

General Reaction

Mechanism

Basic Hydrolysis

Under aqueous basic conditions the epoxide is opened by the attack of hydroxide nucleophile during an SN2 reaction. The epoxide oxygen forms an alkoxide which is subsequently protonated by water forming the 1,2-diol product. If the epoxide is asymmetric the incoming hydroxide nucleophile will preferable attack the less substituted epoxide carbon. Because the reaction takes place by an SN2 mechanism the two -OH groups in the product will be trans to each other.

General Reaction

Mechanism

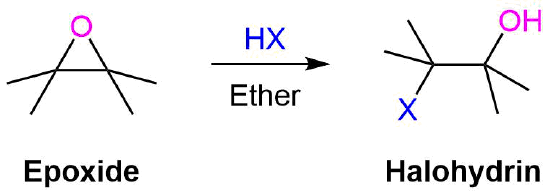

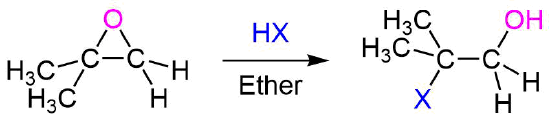

Epoxide Ring-Opening by HX

Epoxides can also be opened by anhydrous acids (HX) to form a trans halohydrin. When both the epoxide carbons are either primary or secondary the halogen anion will attack the less substituted carbon through an SN2 like reaction. However, if one of the epoxide carbons is tertiary, the halogen anion will primarily attack the tertiary carbon in an SN1 like reaction.

General Reaction

Additional Stereochemical Considerations of Ring-Opening

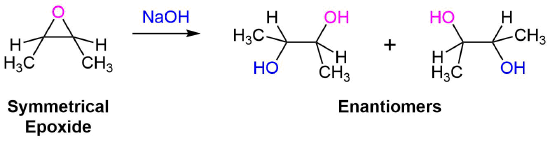

During the ring-opening of an asymmetrical epoxide, the regiochemical control of the reaction usually allows for one stereoisomer to be produced. However, if the epoxide is symmetrical, each epoxide carbon has roughly the same ability to accept the incoming nucleophile. When this occurs the product typically contains a mixture of enantiomers.

Contributors and Attributions

- Layne Morsch (University of Illinois Springfield)

William Reusch, Professor Emeritus (Michigan State U.), Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry