4.2.3: Ionic Charge Patterns

- Page ID

- 370284

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Explain the bonding nature of ionic compounds.

- Relating microscopic bonding properties to macroscopic solid properties.

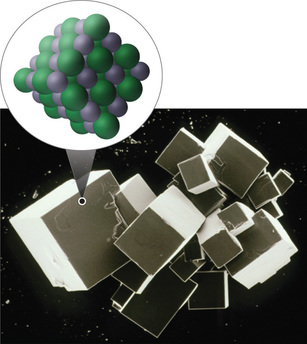

One example of an ionic compound is sodium chloride (NaCl; Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), formed from sodium and chlorine. In forming chemical compounds, many elements have a tendency to gain or lose enough electrons to attain the same number of electrons as the noble gas closest to them in the periodic table. When sodium and chlorine come into contact, each sodium atom gives up an electron to become a Na+ ion, with 11 protons in its nucleus but only 10 electrons (like neon), and each chlorine atom gains an electron to become a Cl− ion, with 17 protons in its nucleus and 18 electrons (like argon), as shown in part (b) in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). Solid sodium chloride contains equal numbers of cations (Na+) and anions (Cl−), thus maintaining electrical neutrality.

Consistent with a tendency to have the same number of electrons as the nearest noble gas, when forming ions, elements in groups 1, 2, and 3 tend to lose one, two, and three electrons, respectively, to form cations, such as Na+ and Mg2+. They then have the same number of electrons as the nearest noble gas: neon. Similarly, K+, Ca2+, and Sc3+ have 18 electrons each, like the nearest noble gas: argon. In addition, the elements in group 13 lose three electrons to form cations, such as Al3+, again attaining the same number of electrons as the noble gas closest to them in the periodic table. Because the lanthanides and actinides formally belong to group 3, the most common ion formed by these elements is M3+, where M represents the metal. Conversely, elements in groups 17, 16, and 15 often react to gain one, two, and three electrons, respectively, to form ions such as Cl−, S2−, and P3−. Ions such as these, which contain only a single atom, are called monatomic ions. The charges of most monatomic ions derived from the main group elements can be predicted by simply looking at the periodic table and counting how many columns an element lies from the extreme left or right. For example, barium (in Group 2) forms Ba2+ to have the same number of electrons as its nearest noble gas, xenon; oxygen (in Group 16) forms O2− to have the same number of electrons as neon; and cesium (in Group 1) forms Cs+, which has the same number of electrons as xenon. Note that this method is ineffective for most of the transition metals. Some common monatomic ions are listed in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Elements in Groups 1, 2, and 3 tend to form 1+, 2+, and 3+ ions, respectively; elements in Groups 15, 16, and 17 tend to form 3−, 2−, and 1− ions, respectively.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 13 | Group 15 | Group 16 | Group 17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li+ lithium | Be2+ beryllium | N3− nitride (azide) | O2− oxide | F− fluoride | ||

| Na+ sodium | Mg2+ magnesium | Al3+ aluminum | P3− phosphide | S2− sulfide | Cl− chloride | |

| K+ potassium | Ca2+ calcium | Sc3+ scandium | Ga3+ gallium | As3− arsenide | Se2− selenide | Br− bromide |

| Rb+ rubidium | Sr2+ strontium | Y3+ yttrium | In3+ indium | Te2− telluride | I− iodide | |

| Cs+ cesium | Ba2+ barium | La3+ lanthanum |

Predict the charge on the most common monatomic ion formed by each element.

- aluminum, used in the quantum logic clock, the world’s most precise clock

- selenium, used to make ruby-colored glass

- yttrium, used to make high-performance spark plugs

Given: element

Asked for: ionic charge

Strategy:

- Identify the group in the periodic table to which the element belongs. Based on its location in the periodic table, decide whether the element is a metal, which tends to lose electrons; a nonmetal, which tends to gain electrons; or a semimetal, which can do either.

- After locating the noble gas that is closest to the element, determine the number of electrons the element must gain or lose to have the same number of electrons as the nearest noble gas.

Solution:

- A Aluminum is a metal in group 13; consequently, it will tend to lose electrons. B The nearest noble gas to aluminum is neon. Aluminum will lose three electrons to form the Al3+ ion, which has the same number of electrons as neon.

- A Selenium is a nonmetal in group 16, so it will tend to gain electrons. B The nearest noble gas is krypton, so we predict that selenium will gain two electrons to form the Se2− ion, which has the same number of electrons as krypton.

- A Yttrium is in group 3, and elements in this group are metals that tend to lose electrons. B The nearest noble gas to yttrium is krypton, so yttrium is predicted to lose three electrons to form Y3+, which has the same number of electrons as krypton.

Predict the charge on the most common monatomic ion formed by each element.

- calcium, used to prevent osteoporosis

- iodine, required for the synthesis of thyroid hormones

- lithium

- Answer a

-

Ca2+

- Answer b

-

I−

- Answer c

-

Li+

Ions of Atoms: Ions of Atoms, YouTube(opens in new window) [youtu.be]