4.2: Representing ionic and molecular compounds and molecules

- Page ID

- 217261

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Skills to Develop

- Symbolize the composition of molecules using molecular formulas and empirical formulas

- Represent the bonding arrangement of atoms within molecules using structural formulas

Communicating the identity and composition of chemicals is an imperative skill for scientists and there are a variety of methods that can be used. Each method has a set of rules, and communicates different types of information about the compound or molecules. This section explains the use of chemical formulas for covalent molecules. The next section will discuss naming, or nomenclature of molecular and ionic compounds. The use of chemical formulas and nomenclature are used in academic and industrial settings and can be important for engineers, biologists, geologists, medical professionals and many others.

Chemical Formulas for Covalent Compounds and Molecules

A molecular formula is a representation of a molecule that uses chemical symbols to indicate the types of atoms followed by subscripts to show the number of atoms of each type in the molecule. (A subscript is used only when more than one atom of a given type is present.) Molecular formulas are also used as abbreviations for the names of compounds.

An empirical formula gives shows the composition of a compound given as the simplest whole-number ratio of atoms.

The structural formula for a compound gives the same information as its molecular formula (the types and numbers of atoms in the molecule), and also shows how the atoms are connected in the molecule.

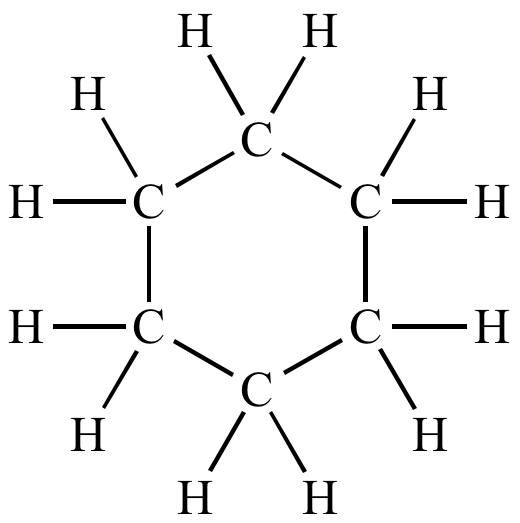

For example, the molecule cyclohexane is comprised of six carbon atoms and twelve hydrogen atoms; the carbon atoms are covalently bonded in a circular chain and two hydrogen atoms are covalently bonded to each carbon atom. The molecular formula for cyclohexane is C6H12 and the empirical formula of cyclohexane is C2H6. Notice how the molecular formula provides more information than the empirical formula - the actual number of atoms compared to the ratio of the atoms. The structural formula also shows the connectivity of those atoms with a straight line indicating a single covalent bond (sharing of two electrons). Figure 1 shows the structural formula for cyclohexane

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): The structural formula of cyclohexane

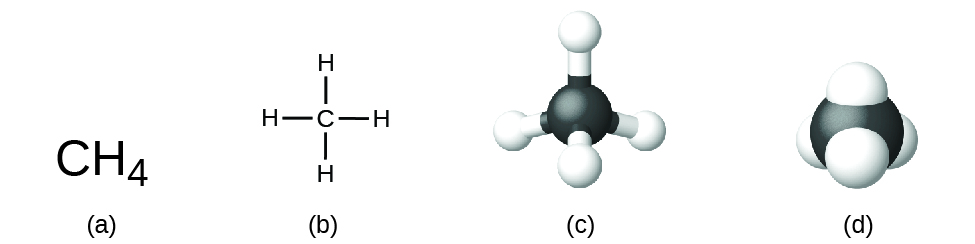

Two other common representations of molecular (covalent) molecules and compounds are the ball-and-stick model and the space-filling model. A ball-and-stick model shows the geometric arrangement of the atoms with atomic sizes not to scale, and a space-filling model shows the relative sizes of the atoms. Figure two shows the molecular and structural formulas for methane and the ball and stick and space filling models for methane.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): A methane molecule can be represented as (a) a molecular formula, (b) a structural formula, (c) a ball-and-stick model, and (d) a space-filling model. Carbon and hydrogen atoms are represented by black and white spheres, respectively.

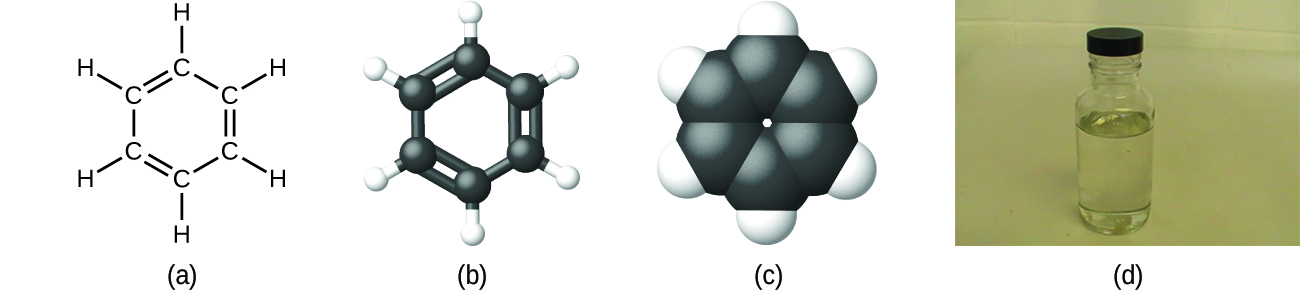

In many cases, the molecular formula of a substance is derived from experimental determination of both its empirical formula and its molecular mass (the sum of atomic masses for all atoms composing the molecule). For example, it can be determined experimentally that benzene contains two elements, carbon (C) and hydrogen (H), and that for every carbon atom in benzene, there is one hydrogen atom. Thus, the empirical formula is CH. An experimental determination of the molecular mass reveals that a molecule of benzene contains six carbon atoms and six hydrogen atoms, so the molecular formula for benzene is C6H6 (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Benzene, C6H6, is produced during oil refining and has many industrial uses. A benzene molecule can be represented as (a) a structural formula, (b) a ball-and-stick model, and (c) a space-filling model. (d) Benzene is a clear liquid. (credit d: modification of work by Sahar Atwa).

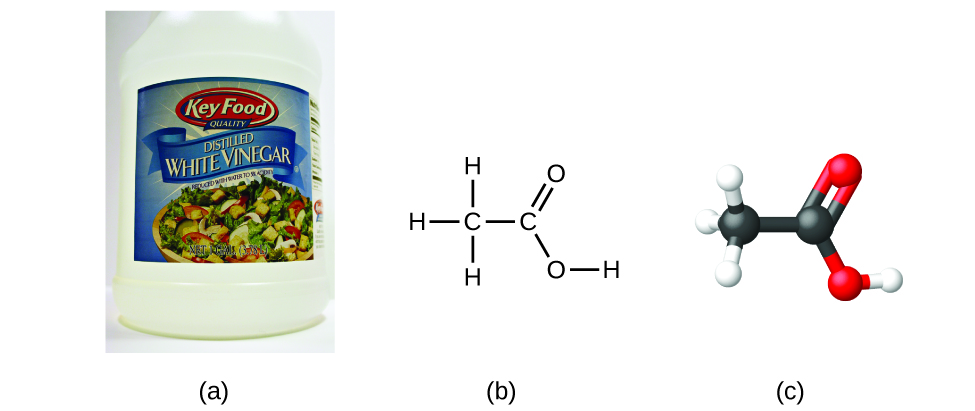

If we know a compound’s formula, we can easily determine the empirical formula. (This is somewhat of an academic exercise; the reverse chronology is generally followed in actual practice.) For example, the molecular formula for acetic acid, the component that gives vinegar its sharp taste, is C2H4O2. This formula indicates that a molecule of acetic acid (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)) contains two carbon atoms, four hydrogen atoms, and two oxygen atoms. The ratio of atoms is 2:4:2. Dividing by the lowest common denominator (2) gives the simplest, whole-number ratio of atoms, 1:2:1, so the empirical formula is CH2O. Note that a molecular formula is always a whole-number multiple of an empirical formula.

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\): (a) Vinegar contains acetic acid, C2H4O2, which has an empirical formula of CH2O. It can be represented as (b) a structural formula and (c) as a ball-and-stick model. (credit a: modification of work by “HomeSpot HQ”/Flickr)

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Empirical and Molecular Formulas

Molecules of glucose (blood sugar) contain 6 carbon atoms, 12 hydrogen atoms, and 6 oxygen atoms. What are the molecular and empirical formulas of glucose?

Solution

The molecular formula is C6H12O6 because one molecule actually contains 6 C, 12 H, and 6 O atoms. The simplest whole-number ratio of C to H to O atoms in glucose is 1:2:1, so the empirical formula is CH2O.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A molecule of metaldehyde (a pesticide used for snails and slugs) contains 8 carbon atoms, 16 hydrogen atoms, and 4 oxygen atoms. What are the molecular and empirical formulas of metaldehyde?

- Answer

-

Molecular formula, C8H16O4; empirical formula, C2H4O

Learn More about Atoms, Molecules and Molecular Formulas

Click the link to use a simulator.

Isomers: A preview of organic chemistry

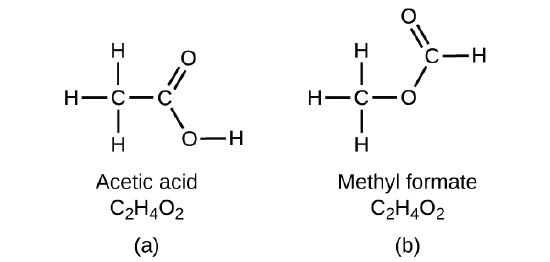

It is important to be aware that it may be possible for the same atoms to be arranged in different ways: Compounds with the same molecular formula may have different atom-to-atom bonding and therefore different structures. For example, could there be another compound with the same formula as acetic acid, C2H4O2? And if so, what would be the structure of its molecules?

If you predict that another compound with the formula C2H4O2 could exist, then you demonstrated good chemical insight and are correct. Two C atoms, four H atoms, and two O atoms can also be arranged to form methyl formate, which is used in manufacturing, as an insecticide, and for quick-drying finishes. Methyl formate molecules have one of the oxygen atoms between the two carbon atoms, differing from the arrangement in acetic acid molecules. Acetic acid and methyl formate are examples of isomers—compounds with the same chemical formula but different molecular structures (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). Note that this small difference in the arrangement of the atoms has a major effect on their respective chemical properties. You would certainly not want to use a solution of methyl formate as a substitute for a solution of acetic acid (vinegar) when you make salad dressing.

Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\): Molecules of (a) acetic acid and methyl formate (b) are structural isomers; they have the same formula (C2H4O2) but different structures (and therefore different chemical properties).

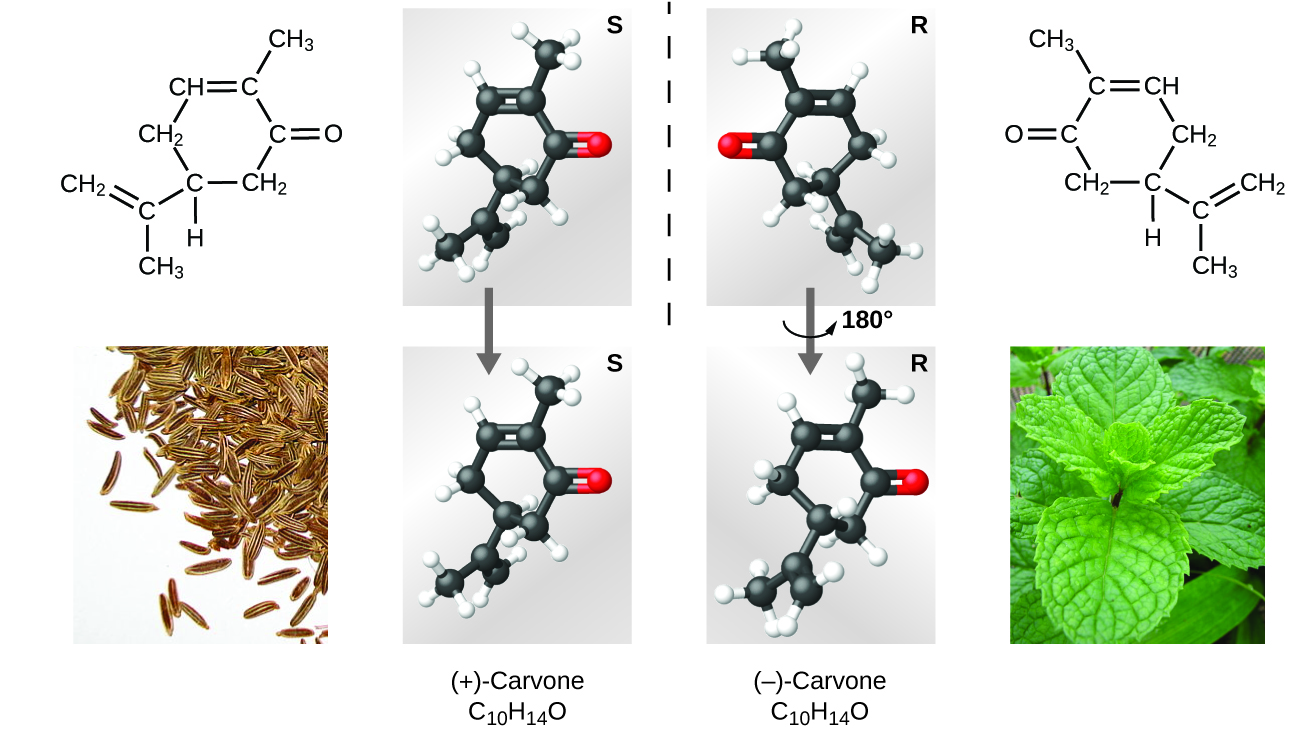

Many other types of isomers exist (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Acetic acid and methyl formate are structural isomers, compounds in which the molecules differ in how the atoms are connected to each other. There are also various types of spatial isomers, in which the relative orientations of the atoms in space can be different. For example, the compound carvone (found in caraway seeds, spearmint, and mandarin orange peels) consists of two isomers that are mirror images of each other. S-(+)-carvone smells like caraway, and R-(−)-carvone smells like spearmint. To learn more about these types of isomers, students can take an organic chemistry course!

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\): Molecules of carvone are spatial isomers; they only differ in the relative orientations of the atoms in space. (credit bottom left: modification of work by “Miansari66”/Wikimedia Commons; credit bottom right: modification of work by Forest & Kim Starr)

Molecules made up of a single element

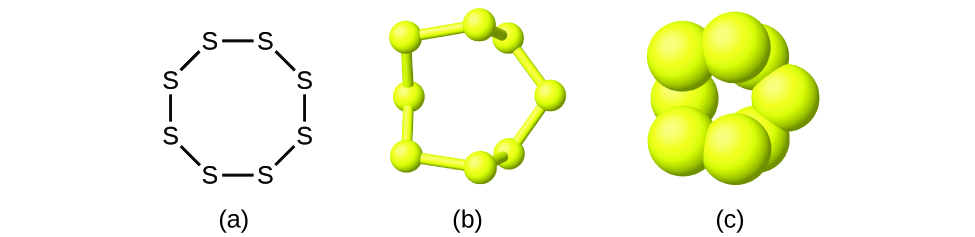

Although many elements consist of discrete, individual atoms, some exist as molecules made up of two or more atoms of the element chemically bonded together. For example, most samples of the elements hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen are composed of molecules that contain two atoms each (called diatomic molecules) and thus have the molecular formulas H2, O2, and N2, respectively. Other elements commonly found as diatomic molecules are fluorine (F2), chlorine (Cl2), bromine (Br2), and iodine (I2). The most common form of the element sulfur is composed of molecules that consist of eight atoms of sulfur; its molecular formula is S8 (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): A molecule of sulfur is composed of eight sulfur atoms and is therefore written as S8. It can be represented as (a) a structural formula, (b) a ball-and-stick model, and (c) a space-filling model. Sulfur atoms are represented by yellow spheres.

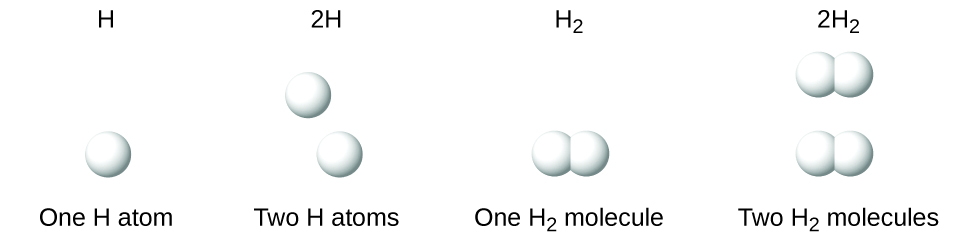

It is important to note that a subscript following a symbol and a number in front of a symbol do not represent the same thing; for example, H2 and 2H represent distinctly different species. H2 is a molecular formula; it represents a diatomic molecule of hydrogen, consisting of two atoms of the element that are chemically bonded together. The expression 2H, on the other hand, indicates two separate hydrogen atoms that are not combined as a unit. The expression 2H2 represents two molecules of diatomic hydrogen (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): The symbols H, 2H, H2, and 2H2 represent very different entities.

Summary

A molecular formula uses chemical symbols and subscripts to indicate the exact numbers of different atoms in a molecule or compound. An empirical formula gives the simplest, whole-number ratio of atoms in a compound. A structural formula indicates the bonding arrangement of the atoms in the molecule. Ball-and-stick and space-filling models show the geometric arrangement of atoms in a molecule. Isomers are compounds with the same molecular formula but different arrangements of atoms.

Going Beyond

What is it that chemists do? According to Lee Cronin, chemists make very complicated molecules by "chopping up" small molecules and "reverse engineering" them. He wonders if we could "make a really cool universal chemistry set" by what he calls "app-ing" chemistry. Could we "app" chemistry?

Video \(\PageIndex{2}\): 2012 TED talk about Cronin's idea to "print" medicine.

Glossary

- empirical formula

- formula showing the composition of a compound given as the simplest whole-number ratio of atoms

- isomers

- compounds with the same chemical formula but different structures

- molecular formula

- formula indicating the composition of a molecule of a compound and giving the actual number of atoms of each element in a molecule of the compound.

- spatial isomers

- compounds in which the relative orientations of the atoms in space differ

- structural isomer

- one of two substances that have the same molecular formula but different physical and chemical properties because their atoms are bonded differently

- structural formula

- shows the atoms in a molecule and how they are connected

Contributors

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).

- Adelaide Clark, Oregon Institute of Technology