Learning Objective

- Learn what science is and how it works

Chemistry is a branch of science. Although science itself is difficult to define exactly, the following definition can serve as starting point. Science is the process of knowing about the natural universe through observation and experiment. Science is not the only process of knowing (e.g., the ancient Greeks simply sat and thought), but it has evolved over more than 350 years into the best process that humanity has devised to date to learn about the universe around us.

The process of science is usually stated as the scientific method, which is rather naïvely described as follows:

- state a hypothesis,

- test the hypothesis, and

- refine the hypothesis.

Actually, however, the process is not that simple. (For example, I don’t go into my lab every day and exclaim, “I am going to state a hypothesis today and spend the day testing it!”) The process is not that simple because science and scientists have a body of knowledge that has already been identified as coming from the highest level of understanding, and most scientists build from that body of knowledge.

An educated guess about how the natural universe works is called a hypothesis. A scientist who is familiar with how part of the natural universe works—say, a chemist—is interested in furthering that knowledge. That person makes a reasonable guess—a hypothesis—that is designed to see if the universe works in a new way as well. Here’s an example of a hypothesis: “if I mix one part of hydrogen with one part of oxygen, I can make a substance that contains both elements.”

For a hypothesis to be termed a scientific hypothesis, it has to be something that can be supported or refuted through carefully crafted experimentation or observation.

Most good hypotheses are grounded in previously understood knowledge and represent a testable extension of that knowledge. The scientist then devises ways to test if that guess is, or is not, correct. That is, the scientist plans experiments. Experiments are tests of the natural universe to see if a guess (hypothesis) is correct. An experiment to test our previous hypothesis would be to actually mix hydrogen and oxygen and see what happens. Most experiments include observations of small, well-defined parts of the natural universe designed to see results of the experiments.

A Scientific Hypothesis

A hypothesis is often written in the form of an if/then statement that gives a possibility (if) and explains what may happen because of the possibility (then). For example, if eating elemental sulfur repels ticks, then someone that is eating sulfur every day will not get ticks.

Why do we have to do experiments? Why do we have to test? Because the natural universe is not always so obvious, experiments are necessary. For example, it is fairly obvious that if you drop an object from a height, it will fall. Several hundred years ago (coincidentally, near the inception of modern science), the concept of gravity explained that test. However, is it obvious that the entire natural universe is composed of only about 115 fundamental chemical building blocks called elements? This wouldn’t seem true if you looked at the world around you and saw all the different forms matter can take. In fact, the concept of the element is only about 200 years old, and the last naturally occurring element was identified about 80 years ago. It took decades of tests and millions of experiments to establish what the elements actually are. These are just two examples; a myriad of such examples exists in chemistry and science in general.

When enough evidence has been collected to establish a general principle of how the natural universe works, the evidence is summarized in a theory. A theory is a general statement that explains a large number of observations. “All matter is composed of atoms” is a general statement, a theory, that explains many observations in chemistry. A theory is a very powerful statement in science. There are many statements referred to as “the theory of _______” or the “______ theory” in science (where the blanks represent a word or concept). When written in this way, theories indicate that science has an overwhelming amount of evidence of its correctness. We will see several theories in the course of this text.

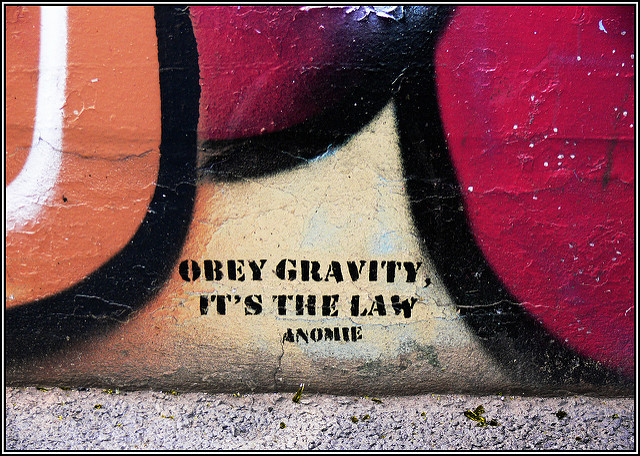

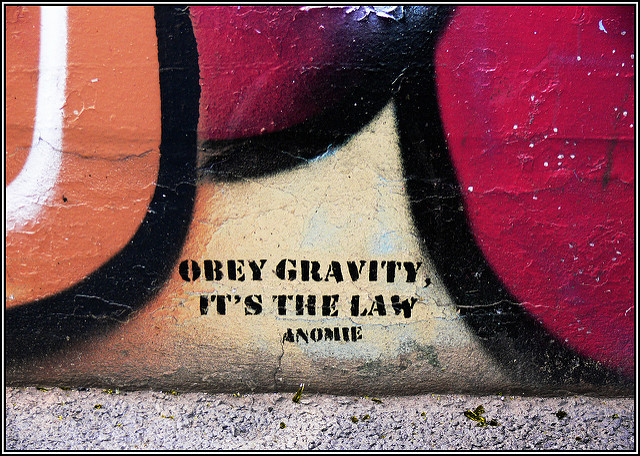

A specific statement that is thought to be never violated by the entire natural universe is called a law. A scientific law is the highest understanding of the natural universe that science has and is thought to be inviolate. For example, the fact that all matter attracts all other matter—the law of gravitation—is one such law. Note that the terms theory and law used in science have slightly different meanings from those in common usage; theory is often used to mean hypothesis (“I have a theory…”), whereas a law is an arbitrary limitation that can be broken but with potential consequences (such as speed limits). Here again, science uses these terms differently, and it is important to apply their proper definitions when you use these words in science. (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\))

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Defining a law. Does this graffiti mean “law” the way science defines “law”? Image used with permission (CC BY-SA-NC-ND; Koppenbadger).

There is an additional phrase in our definition of science: “the natural universe.” Science is concerned only with the natural universe. What is the natural universe? It’s anything that occurs around us, well, naturally. Stars, planets, the appearance of life on earth, and how animals, plants, and other matter function are all part of the natural universe. Science is concerned with that—and only that.

Of course, there are other things that concern us. For example, is the English language part of science? Most of us can easily answer no; English is not science. English is certainly worth knowing (at least for people in predominantly English-speaking countries), but why isn’t it science? English, or any human language, isn’t science because ultimately it is contrived; it is made up. Think of it: the word spelled b-l-u-e represents a certain color, and we all agree what color that is. But what if we used the word h-a-r-d-n-r-f to describe that color? (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)) That would be fine—as long as everyone agreed. Anyone who has learned a second language must initially wonder why a certain word is used to describe a certain concept; ultimately, the speakers of that language agreed that a particular word would represent a particular concept. It was contrived.

That doesn’t mean language isn’t worth knowing. It is very important in society. But it’s not science. Science deals only with what occurs naturally.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): English Is Not Science. How would you describe this color? Blue or hard? Either way, you’re not doing science.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Identifying science

Which of the following fields would be considered science?

- geology, the study of the earth

- ethics, the study of morality

- political science, the study of governance

- biology, the study of living organisms

Solution

- Because the earth is a natural object, the study of it is indeed considered part of science.

- Ethics is a branch of philosophy that deals with right and wrong. Although these are useful concepts, they are not science.

- There are many forms of government, but all are created by humans. Despite the fact that the word science appears in its name, political science is not true science.

- Living organisms are part of the natural universe, so the study of them is part of science.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Which is part of science, and which is not?

- dynamics, the study of systems that change over time

- aesthetics, the concept of beauty

- Answer A

-

science

- Answer B

-

not science

The field of science has gotten so big that it is common to separate it into more specific fields. First, there is mathematics, the language of science. All scientific fields use mathematics to express themselves—some more than others. Physics and astronomy are scientific fields concerned with the fundamental interactions between matter and energy. Chemistry, as defined previously, is the study of the interactions of matter with other matter and with energy. Biology is the study of living organisms, while geology is the study of the earth. Other sciences can be named as well. Understand that these fields are not always completely separate; the boundaries between scientific fields are not always readily apparent. Therefore, a scientist may be labeled a biochemist if he or she studies the chemistry of biological organisms.

Finally, understand that science can be either qualitative or quantitative. Qualitative implies a description of the quality of an object. For example, physical properties are generally qualitative descriptions: sulfur is yellow, your math book is heavy, or that statue is pretty. A quantitative description represents the specific amount of something; it means knowing how much of something is present, usually by counting or measuring it. As such, some quantitative descriptions would include 25 students in a class, 650 pages in a book, or a velocity of 66 miles per hour. Quantitative expressions are very important in science; they are also very important in chemistry.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): qualitative vs. quantitative Descriptions

Identify each statement as either a qualitative description or a quantitative description.

- Gold metal is yellow.

- A ream of paper has 500 sheets in it.

- The weather outside is snowy.

- The temperature outside is 24 degrees Fahrenheit.

Solution

- Because we are describing a physical property of gold, this statement is qualitative.

- This statement mentions a specific amount, so it is quantitative.

- The word snowy is a description of how the day is; therefore, it is a qualitative statement.

- In this case, the weather is described with a specific quantity—the temperature. Therefore, it is quantitative.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Are these qualitative or quantitative statements?

- Roses are red, and violets are blue.

- Four score and seven years ago….

- Answer A

-

qualitative

- Answer B

-

quantitative

Food and Drink App: Carbonated Beverages

Some of the simple chemical principles discussed in this chapter can be illustrated with carbonated beverages: sodas, beer, and sparkling wines. Each product is produced in a different way, but they all have one thing in common. They are solutions of carbon dioxide dissolved in water.

Carbon dioxide is a compound composed of carbon and oxygen. Under normal conditions, it is a gas. If you cool it down enough, it becomes a solid known as dry ice. Carbon dioxide is an important compound in the cycle of life on earth.

Even though it is a gas, carbon dioxide can dissolve in water, just like sugar or salt can dissolve in water. When that occurs, we have a homogeneous mixture, or a solution, of carbon dioxide in water. However, very little carbon dioxide can dissolve in water. If the atmosphere were pure carbon dioxide, the solution would be only about 0.07% carbon dioxide. In reality, the air is only about 0.03% carbon dioxide, so the amount of carbon dioxide in water is reduced proportionally.

However, when soda and beer are made, manufacturers do two important things: they use pure carbon dioxide gas, and they use it at very high pressures. With higher pressures, more carbon dioxide can dissolve in the water. When the soda or beer container is sealed, the high pressure of carbon dioxide gas remains inside the package. (Of course, there are more ingredients in soda and beer besides carbon dioxide and water.)

When you open a container of soda or beer, you hear a distinctive hiss as the excess carbon dioxide gas escapes. But something else happens as well. The carbon dioxide in the solution comes out of solution as a bunch of tiny bubbles. These bubbles impart a pleasing sensation in the mouth, so much so that the soda industry sold over 225 billion servings of soda in the United States alone in 2009.

Some sparkling wines are made in the same way—by forcing carbon dioxide into regular wine. Some sparkling wines (including champagne) are made by sealing a bottle of wine with some yeast in it. The yeast ferments, a process by which the yeast converts sugars into energy and excess carbon dioxide. The carbon dioxide produced by the yeast dissolves in the wine. Then, when the champagne bottle is opened, the increased pressure of carbon dioxide is released, and the drink bubbles just like an expensive glass of soda.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): Carbonated Beverages © Thinkstock Soda, beer, and sparkling wine take advantage of the properties of a solution of carbon dioxide in water.

Key Takeaways

- Science is a process of knowing about the natural universe through observation and experiment.

- Scientists go through a rigorous process to determine new knowledge about the universe; this process is generally referred to as the scientific method.

- Science is broken down into various fields, of which chemistry is one.

- Science, including chemistry, is both qualitative and quantitative.