Chapter 6.2: Hybrid Orbitals

- Page ID

- 17712

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)

Learning Objectives

- To describe the bonding in simple compounds using valence bond theory.

Lewis structures provide no information about the shapes of molecules, being limited to which atoms are connected to each other and whether bonds are single, double or triple. A more sophisticated treatment of bonding is needed to begin to understand the shapes of molecules. In this section, we present a quantum mechanical description of bonding, in which bonding electrons are viewed as being localized between the nuclei of the bonded atoms. The overlap of bonding orbitals is substantially increased through a process called hybridization, which results in the formation of stronger bonds. Using this model we will be able to predict the shapes of the molecules.

Valence Bond Theory: A Localized Bonding Approach

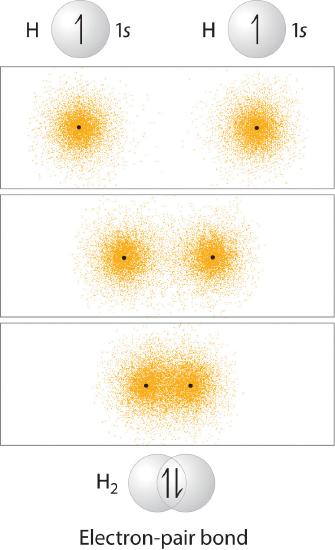

In Chapter 4, you learned that as two hydrogen atoms approach each other from an infinite distance, the energy of the system reaches a minimum. This region of minimum energy in the energy diagram corresponds to the formation of a covalent bond between the two atoms at an H–H distance of 74 pm (Figure 4.4.2). According to quantum mechanics, bonds form between atoms because their atomic orbitals overlap, with each region of overlap accommodating a maximum of two electrons with opposite spin, in accordance with the Pauli principle. In this case, a bond forms between the two hydrogen atoms when the singly occupied 1s atomic orbital of one hydrogen atom overlaps with the singly occupied 1s atomic orbital of a second hydrogen atom. Electron density between the nuclei is increased because of this orbital overlap and results in a localized electron-pair bond (Figure 6.2.1).

Figure 6.2.1 Overlap of Two Singly Occupied Hydrogen 1s Atomic Orbitals Produces an H–H Bond in H2

The formation of H2 from two hydrogen atoms, each with a single electron in a 1s orbital, occurs as the electrons are shared to form an electron-pair bond, as indicated schematically by the gray spheres and black arrows. The orange electron density distributions show that the formation of an H2 molecule increases the electron density in the region between the two positively charged nuclei.

Although Lewis structures also contain localized electron-pair bonds, it does not use an atomic orbital approach to predict the stability and direction of the bond. Doing so forms the basis for a description of chemical bonding known as valence bond theory (A localized bonding model that assumes that the strength of a covalent bond is proportional to the amount of overlap between atomic orbitals and that an atom can use different combinations of atomic orbitals (hybrids) to maximize the overlap between bonded atoms.), which is built on two assumptions:

- The strength of a covalent bond is proportional to the amount of overlap between atomic orbitals; that is, the greater the overlap, the more stable the bond.

- An atom can use different combinations of atomic orbitals to maximize the overlap of orbitals used by bonded atoms.

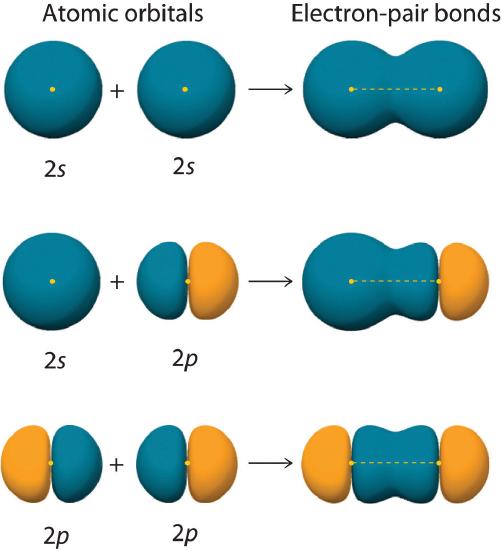

Figure 6.2.2 shows an electron-pair bond formed by the overlap of two ns atomic orbitals, two np atomic orbitals, and an ns and an np orbital where n = 2. Maximum overlap occurs between orbitals with the same spatial orientation and similar energies.

Figure 6.2.2 Three Different Ways to Form an Electron-Pair Bond

An electron-pair bond can be formed by the overlap of any of the following combinations of two singly occupied atomic orbitals: two ns atomic orbitals (a), an ns and an np atomic orbital (b), and two np atomic orbitals (c) where n = 2. The positive lobe is indicated in yellow, and the negative lobe is in blue.

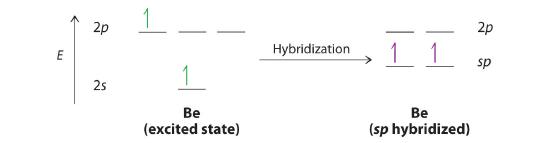

Let’s examine the bonds in BeH2, for example. Its bonding can also be described using an atomic orbital approach. Beryllium has a 1s22s2 electron configuration, and each H atom has a 1s1 electron configuration. Because the Be atom has a filled 2s subshell, however, it has no singly occupied orbitals available to overlap with the singly occupied 1s orbitals on the H atoms. If a singly occupied 1s orbital on hydrogen were to overlap with a filled 2s orbital on beryllium, the resulting bonding orbital would contain three electrons, but the maximum allowed by quantum mechanics is two. How then is beryllium able to bond to two hydrogen atoms? One way would be to add enough energy to excite one of its 2s electrons into an empty 2p orbital and reverse its spin, in a process called promotion (The excitation of an electron from a filled ns2 to an nsnp valence orbital):

In this excited state, the Be atom would have two singly occupied atomic orbitals (the 2s and one of the 2p orbitals), each of which could overlap with a singly occupied 1s orbital of an H atom to form an electron-pair bond. Although this would produce BeH2, the two Be–H bonds would not be equivalent: the 1s orbital of one hydrogen atom would overlap with a Be 2s orbital, and the 1s orbital of the other hydrogen atom would overlap with an orbital of a different energy, a Be 2p orbital. Experimental evidence indicates, however, that the two Be–H bonds have identical energies. To resolve this discrepancy and explain how molecules such as BeH2 form, scientists developed the concept of hybridization.

Hybridization of s and p Orbitals

The localized bonding approach uses a process called hybridization (A process in which two or more atomic orbitals that are similar in energy but not equivalent are combined mathematically to produce sets of equivalent orbitals that are properly oriented to form bonds), in which atomic orbitals that are similar in energy but not equivalent are combined mathematically to produce sets of equivalent orbitals that are properly oriented to form bonds. These new combinations are called hybrid atomic orbitalsNew atomic orbitals formed from the process of hybridization. because they are produced by combining (hybridizing) two or more atomic orbitals from the same atom.

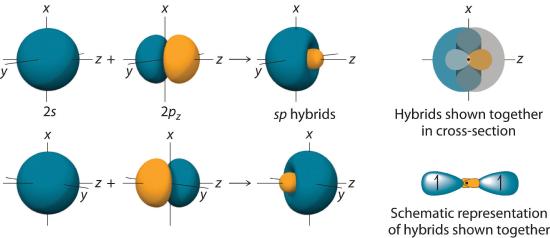

In BeH2, we can generate two equivalent orbitals by combining the 2s orbital of beryllium and any one of the three degenerate 2p orbitals. By taking the sum and the difference of Be 2s and 2pz atomic orbitals, for example, we produce two new orbitals with major and minor lobes oriented along the z-axes, as shown in Figure 6.2.3. Because the difference A − B can also be written as A + (−B), in Figure 6.2.3 and subsequent figures we have reversed the phase(s) of the orbital being subtracted, which is the same as multiplying it by −1 and adding. This gives us Equation 6.2.1, where the value \( 1/\sqrt{2} \) is needed mathematically to indicate that the 2s and 2p orbitals contribute equally to each hybrid orbital.

\( sp_{1}=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left ( 2s+2p_{z} \right )\; \; \; and\; \; \; sp_{2}=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left ( 2s-2p_{z} \right ) \tag{6.2.1} \)

Generally we do not use the subsript labels on the two sp orbitals, but we have done so here to emphasize that there are two different orbitals. It is also important to remember that the two sp orbitals are built from orbitals of the same atom and centered on the nucleus of that atom. Later in this chapter we will meet molecular orbitals which are linear combinations of atomic orbitals (LCAO in theoretical chemistry speak) centered on different atoms. It is often difficult for students to figure out the difference

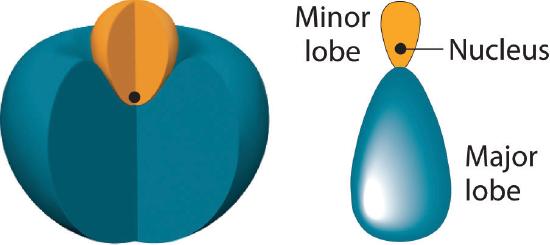

The position of the atomic nucleus with respect to an sp hybrid orbital. The nucleus is actually located slightly inside the minor lobe, not at the node separating the major and minor lobes.

Figure 6.2.3 The Formation of sp Hybrid Orbitals

Taking the mathematical sum and difference of an ns and an np atomic orbital where n = 2 gives two equivalent sp hybrid orbitals oriented at 180° to each other.

The nucleus resides just inside the minor lobe of each orbital. In this case, the new orbitals are called sp hybrids because they are formed from one s and one p orbital. The two new orbitals are equivalent in energy, and their energy is between the energy values associated with pure s and p orbitals, as illustrated in this diagram:

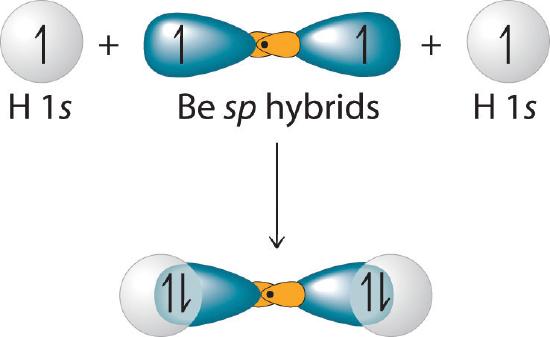

This indicates that each sp hybrid orbital is singly occupied and can bond with a 1s electron of a hydrogen atom. (The two equivalent hybrid orbitals result when one ns orbital and one np orbital are combined (hybridized)). The two sp hybrid orbitals are oriented at 180° from each other. They are equivalent in energy, and their energy is between the energy values associated with pure s and p orbitals. They can now form an electron-pair bond with the singly occupied 1s atomic orbital of one of the H atoms. As shown in Figure 6.2.4, each sp orbital on Be has the correct orientation for the major lobes to overlap with the 1s atomic orbital of an H atom. The formation of two energetically equivalent Be–H bonds produces a linear BeH2 molecule. Thus valence bond theory does what the Lewis electron structurel is able to do; it explains why the bonds in BeH2 are equivalent in energy and why BeH2 has a linear geometry.

Figure 6.2.4 Explanation of the Bonding in BeH2 Using sp Hybrid Orbitals

Each singly occupied sp hybrid orbital on beryllium can form an electron-pair bond with the singly occupied 1s orbital of a hydrogen atom. Because the two sp hybrid orbitals are oriented at a 180° angle, the BeH2 molecule is linear.

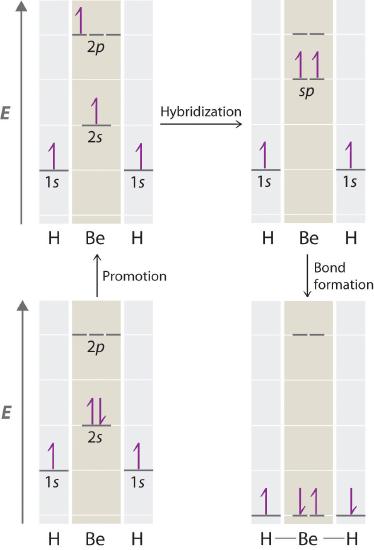

Because both promotion and hybridization require an input of energy, the formation of a set of singly occupied hybrid atomic orbitals is energetically uphill. The overall process of forming a compound with hybrid orbitals will be energetically favorable only if the amount of energy released by the formation of covalent bonds is greater than the amount of energy used to form the hybrid orbitals (Figure 6.1.5 ). As we will see, some compounds are highly unstable or do not exist because the amount of energy required to form hybrid orbitals is greater than the amount of energy that would be released by the formation of additional bonds.

Figure 6.2.5 A Hypothetical Stepwise Process for the Formation of BeH2 from a Gaseous Be Atom and Two Gaseous H Atoms

The promotion of an electron from the 2s orbital of beryllium to one of the 2p orbitals is energetically uphill. The overall process of forming a BeH2 molecule from a Be atom and two H atoms will therefore be energetically favorable only if the amount of energy released by the formation of the two Be–H bonds is greater than the amount of energy required for promotion and hybridization.

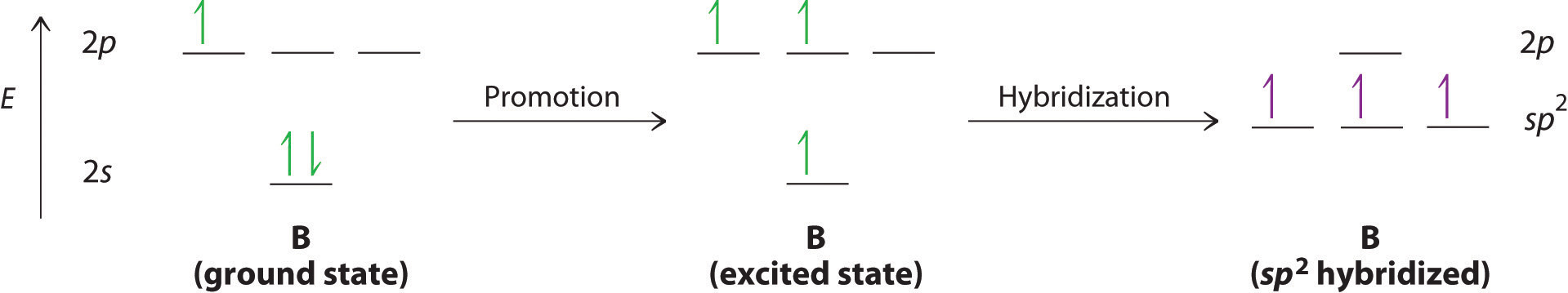

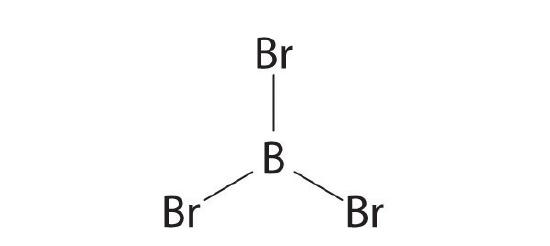

The concept of hybridization also explains why boron, with a 2s22p1 valence electron configuration, forms three bonds with fluorine to produce BF3. The Lewis approach only works on the assumption that molecules with a central atom having LESS than an octet can exist. You may remember that this was one of the handwaves that we had to introduce in the previous chapter discussing Lewis structures.

With only a single unpaired electron in its ground state, boron should form only a single covalent bond. By the promotion of one of its 2s electrons to an unoccupied 2p orbital, however, followed by the hybridization of the three singly occupied orbitals (the 2s and two 2p orbitals), boron acquires a set of three equivalent hybrid orbitals with one electron each, as shown here:

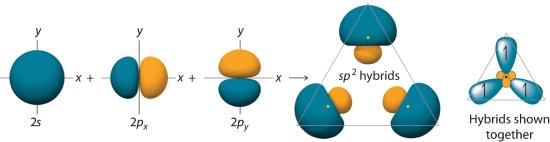

The hybrid orbitals are degenerate and are oriented at 120° angles to each other (Figure 6.2.6). Because the hybrid atomic orbitals are formed from one s and two p orbitals, boron is said to be sp2 hybridized (pronounced “s-p-two” or “s-p-squared”). The singly occupied sp2 hybrid atomic orbitalsThe three equivalent hybrid orbitals that result when one ns orbital and two np orbitals are combined (hybridized). The three sp2 hybrid orbitals are oriented in a plane at 120° from each other. They are equivalent in energy, and their energy is between the energy values associated with pure s and pure p orbitals. can overlap with the singly occupied orbitals on each of the three F atoms to form a trigonal planar structure with three energetically equivalent B–F bonds.

Figure 6.2.6 Formation of sp2 Hybrid Orbitals

Combining one ns and two np atomic orbitals gives three equivalent sp2 hybrid orbitals in a trigonal planar arrangement; that is, oriented at 120° to one another.

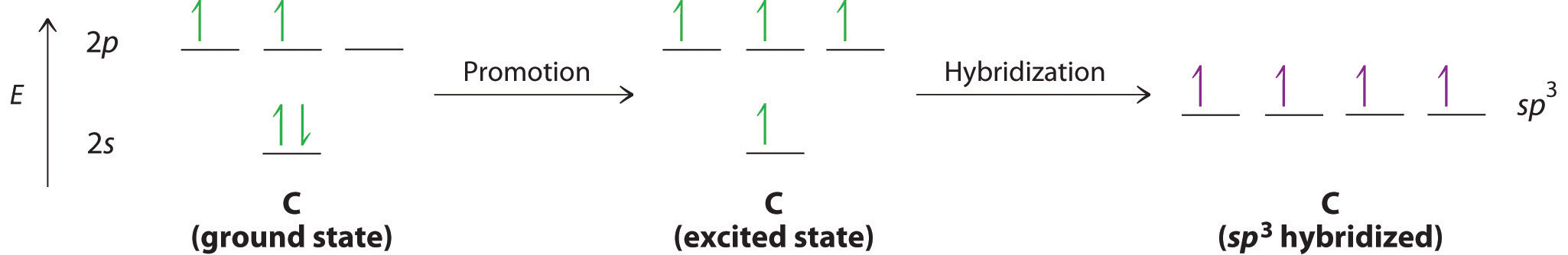

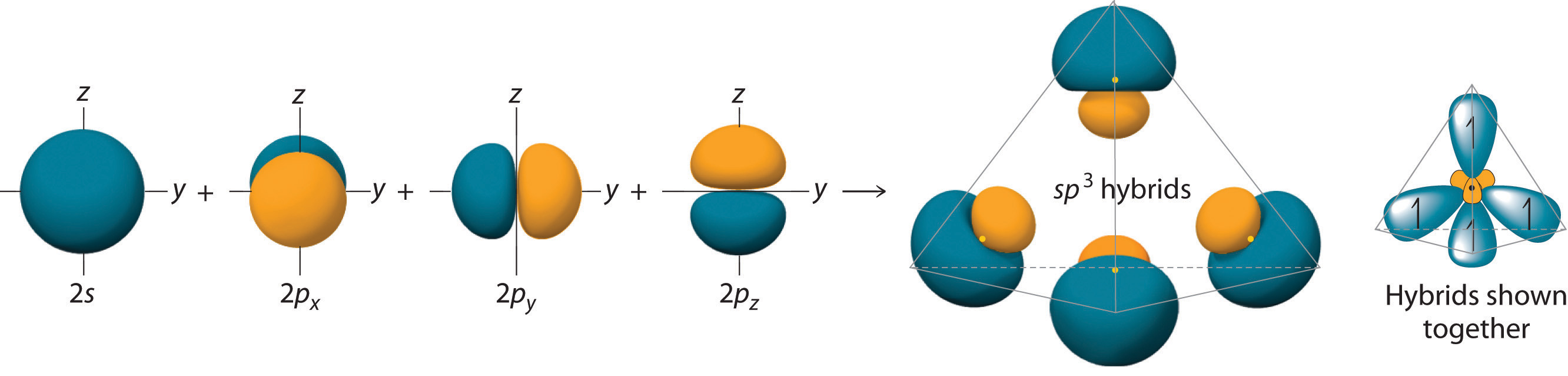

Looking at the 2s22p2 valence electron configuration of carbon, we might expect carbon to use its two unpaired 2p electrons to form compounds with only two covalent bonds. We know, however, that carbon typically forms compounds with four covalent bonds. We can explain this apparent discrepancy by the hybridization of the 2s orbital and the three 2p orbitals on carbon to give a set of four degenerate sp3 (“s-p-three” or “s-p-cubed”) hybrid orbitals, each with a single electron:

The large lobes of the hybridized orbitals are oriented toward the vertices of a tetrahedron, with 109.5° angles between them (Figure 6.2.7). It is rather difficult to visualize a tetrahedron. A simple, though inelegant way of doing so is to stand with one foot forward and the other backwards. Now raise your hands from your sides to above your shoulders.

Like all the hybridized orbitals discussed earlier, the sp3 hybrid atomic orbitals (The four equivalent hybrid orbitals that result when one ns orbital and three np orbitals are combined (hybridized). The four sp3 hybrid orbitals point at the vertices of a tetrahedron, so they are oriented at 109.5° from each other. They are equivalent in energy, and their energy is between the energy values associated with pure s and pure p orbitals. are predicted to be equal in energy.

Figure 6.2.7 Formation of sp3 Hybrid Orbitals

Combining one ns and three np atomic orbitals results in four sp3 hybrid orbitals oriented at 109.5° to one another in a tetrahedral arrangement.

In addition to explaining why some elements form more bonds than would be expected based on their valence electron configurations, and why the bonds formed are equal in energy, valence bond theory explains why these compounds are so stable: the amount of energy released increases with the number of bonds formed. In the case of carbon, for example, much more energy is released in the formation of four bonds than two, so compounds of carbon with four bonds tend to be more stable than those with only two. Carbon does form compounds with only two covalent bonds (such as CH2 or CF2), but these species are highly reactive, unstable intermediates that form in only certain chemical reactions.

Note the Pattern

Valence bond theory explains the number of bonds formed in a compound and the relative bond strengths.

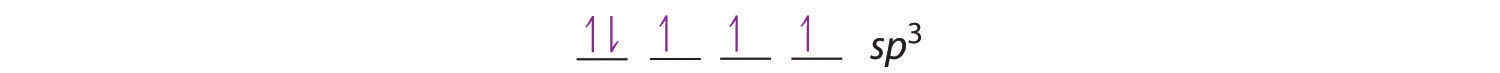

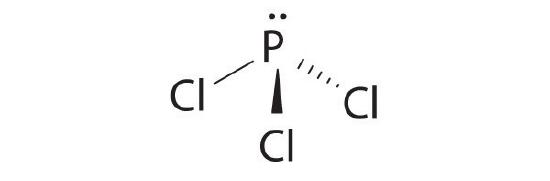

The bonding in molecules such as NH3 or H2O, which have lone pairs on the central atom, can also be described in terms of hybrid atomic orbitals. In NH3, for example, N, with a 2s22p3 valence electron configuration, can hybridize its 2s and 2p orbitals to produce four sp3 hybrid orbitals. Placing five valence electrons in the four hybrid orbitals, we obtain three that are singly occupied and one with a pair of electrons:

The three singly occupied sp3 lobes can form bonds with three H atoms, while the fourth orbital accommodates the lone pair of electrons. Similarly, H2O has an sp3 hybridized oxygen atom that uses two singly occupied sp3 lobes to bond to two H atoms, and two to accommodate the two lone pairs predicted by the VSEPR model. Such descriptions explain the approximately tetrahedral distribution of electron pairs on the central atom in NH3 and H2O. Unfortunately, however, recent experimental evidence indicates that in CH4 and NH3, the hybridized orbitals are not entirely equivalent in energy, making this bonding model an active area of research.

Example 3

Predict the number of electron pairs and molecular geometry in each compound and then describe the hybridization and bonding of all atoms except hydrogen.

- H2S

- CHCl3

Given: two chemical compounds

Asked for: number of electron pairs and molecular geometry, hybridization, and bonding

Strategy:

A Using the approach from Example 1, determine the number of electron pairs and the molecular geometry of the molecule.

B From the valence electron configuration of the central atom, predict the number and type of hybrid orbitals that can be produced. Fill these hybrid orbitals with the total number of valence electrons around the central atom and describe the hybridization.

Solution:

- A H2S has four electron pairs around the sulfur atom with two bonded atoms, so the VSEPR model predicts a molecular geometry that is bent, or V shaped. B Sulfur has a 3s23p4 valence electron configuration with six electrons, but by hybridizing its 3s and 3p orbitals, it can produce four sp3 hybrids. If the six valence electrons are placed in these orbitals, two have electron pairs and two are singly occupied. The two sp3 hybrid orbitals that are singly occupied are used to form S–H bonds, whereas the other two have lone pairs of electrons. Together, the four sp3 hybrid orbitals produce an approximately tetrahedral arrangement of electron pairs, which agrees with the molecular geometry predicted by the VSEPR model.

- A The CHCl3 molecule has four valence electrons around the central atom. In the VSEPR model, the carbon atom has four electron pairs, and the molecular geometry is tetrahedral. B Carbon has a 2s22p2 valence electron configuration. By hybridizing its 2s and 2p orbitals, it can form four sp3 hybridized orbitals that are equal in energy. Eight electrons around the central atom (four from C, one from H, and one from each of the three Cl atoms) fill three sp3 hybrid orbitals to form C–Cl bonds, and one forms a C–H bond. Similarly, the Cl atoms, with seven electrons each in their 3s and 3p valence subshells, can be viewed as sp3 hybridized. Each Cl atom uses a singly occupied sp3 hybrid orbital to form a C–Cl bond and three hybrid orbitals to accommodate lone pairs.

Exercise

Predict the number of electron pairs and molecular geometry in each compound and then describe the hybridization and bonding of all atoms except hydrogen.

- the BF4− ion

- hydrazine (H2N–NH2)

Answer:

- B is sp3 hybridized; F is also sp3 hybridized so it can accommodate one B–F bond and three lone pairs. The molecular geometry is tetrahedral.

- Each N atom is sp3 hybridized and uses one sp3 hybrid orbital to form the N–N bond, two to form N–H bonds, and one to accommodate a lone pair. The molecular geometry about each N is trigonal pyramidal.

Note the Pattern

The number of hybrid orbitals used by the central atom is the same as the number of electron pairs around the central atom.

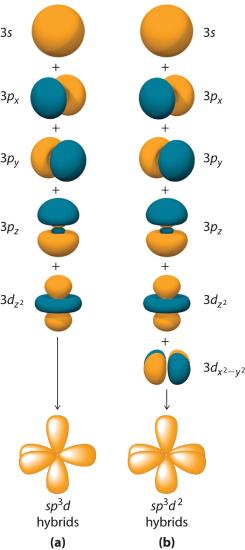

Hybridization Using d Orbitals

Hybridization is not restricted to the ns and np atomic orbitals. The bonding in compounds with central atoms in the period 3 and below can also be described using hybrid atomic orbitals. In these cases, the central atom can use its valence (n − 1)d orbitals as well as its ns and np orbitals to form hybrid atomic orbitals, which allows it to accommodate five or more bonded atoms (as in PF5 and SF6). Using the ns orbital, all three np orbitals, and one (n − 1)d orbital gives a set of five sp3d hybrid orbitals (The five hybrid orbitals that result when one s three p and one d orbitals are combined (hybridized)). that point toward the vertices of a trigonal bipyramid (part (a) in Figure 5.17 ). In this case, the five hybrid orbitals are not all equivalent: three form a triangular array oriented at 120° angles, and the other two are oriented at 90° to the first three and at 180° to each other.

Similarly, the combination of the ns orbital, all three np orbitals, and two nd orbitals gives a set of six equivalent sp3d2 hybrid orbitals (The six equivalent hybrid orbitals that result when one s, three p, and two d orbitals are combined (hybridized). oriented toward the vertices of an octahedron (part (b) in Figure 6.2.8). In the VSEPR model, PF5 and SF6 are predicted to be trigonal bipyramidal and octahedral, respectively, which agrees with a valence bond description in which sp3d or sp3d2 hybrid orbitals are used for bonding.

Figure 6.2.8 Hybrid Orbitals Involving d Orbitals

The formation of a set of (a) five sp3d hybrid orbitals and (b) six sp3d2 hybrid orbitals from ns, np, and nd atomic orbitals where n = 4.

Example 4

What is the hybridization of the central atom in each species? Describe the bonding in each species.

- XeF4

- SO42−

- SF4

Given: three chemical species

Asked for: hybridization of the central atom

Strategy:

A Determine the geometry of the molecule using the strategy in Example 1. From the valence electron configuration of the central atom and the number of electron pairs, determine the hybridization.

B Place the total number of electrons around the central atom in the hybrid orbitals and describe the bonding.

Solution:

- A Xe in XeF4 forms four bonds and has two lone pairs, so its structure is square planar and it has six electron pairs. The six electron pairs form an octahedral arrangement, so the Xe must be sp3d2 hybridized. B With 12 electrons around Xe, four of the six sp3d2 hybrid orbitals form Xe–F bonds, and two are occupied by lone pairs of electrons.

- A The S in the SO42− ion has four electron pairs and has four bonded atoms, so the structure is tetrahedral. The sulfur must be sp3 hybridized to generate four S–O bonds. B Filling the sp3 hybrid orbitals with eight electrons from four bonds produces four filled sp3 hybrid orbitals.

-

A The S atom in SF4 contains five electron pairs and four bonded atoms. The molecule has a seesaw structure with one lone pair:

To accommodate five electron pairs, the sulfur atom must be sp3d hybridized. B Filling these orbitals with 10 electrons gives four sp3d hybrid orbitals forming S–F bonds and one with a lone pair of electrons.

Exercise

What is the hybridization of the central atom in each species? Describe the bonding.

- PCl4+

- BrF3

- SiF62−

Answer:

- sp3 with four P–Cl bonds

- sp3d with three Br–F bonds and two lone pairs

- sp3d2 with six Si–F bonds

Hybridization using d orbitals allows chemists to explain the structures and properties of many molecules and ions. Like most such models, however, it is not universally accepted. Nonetheless, it does explain a fundamental difference between the chemistry of the elements in the period 2 (C, N, and O) and those in period 3 and below (such as Si, P, and S).

Period 2 elements do not form compounds in which the central atom is covalently bonded to five or more atoms, although such compounds are common for the heavier elements. Thus whereas carbon and silicon both form tetrafluorides (CF4 and SiF4), only SiF4 reacts with F− to give a stable hexafluoro dianion, SiF62−. Because there are no 2d atomic orbitals, the formation of octahedral CF62− would require hybrid orbitals created from 2s, 2p, and 3d atomic orbitals. The 3d orbitals of carbon are so high in energy that the amount of energy needed to form a set of sp3d2 hybrid orbitals cannot be equaled by the energy released in the formation of two additional C–F bonds. These additional bonds are expected to be weak because the carbon atom (and other atoms in period 2) is so small that it cannot accommodate five or six F atoms at normal C–F bond lengths due to repulsions between electrons on adjacent fluorine atoms. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, species such as CF62− have never been prepared.

Example 5

What is the hybridization of the oxygen atom in OF4? Is OF4 likely to exist?

Given: chemical compound

Asked for: hybridization and stability

Strategy:

A Predict the geometry of OF4 using the VSEPR model.

B From the number of electron pairs around O in OF4, predict the hybridization of O. Compare the number of hybrid orbitals with the number of electron pairs to decide whether the molecule is likely to exist.

Solution:

A T OF4 will have five electron pairs, resulting in a trigonal bipyramidal geometry with four bonding pairs and one lone pair. B To accommodate five electron pairs, the O atom would have to be sp3d hybridized. The only d orbital available for forming a set of sp3d hybrid orbitals is a 3d orbital, which is much higher in energy than the 2s and 2p valence orbitals of oxygen. As a result, the OF4 molecule is unlikely to exist. In fact, it has not been detected.

Exercise

What is the hybridization of the boron atom in BF63−? Is this ion likely to exist?

Answer: sp3d2 hybridization; no

Summary

The localized bonding model (called valence bond theory) assumes that covalent bonds are formed when atomic orbitals overlap and that the strength of a covalent bond is proportional to the amount of overlap. It also assumes that atoms use combinations of atomic orbitals (hybrids) to maximize the overlap with adjacent atoms. The formation of hybrid atomic orbitals can be viewed as occurring via promotion of an electron from a filled ns2 subshell to an empty np or (n − 1)d valence orbital, followed by hybridization, the combination of the orbitals to give a new set of (usually) equivalent orbitals that are oriented properly to form bonds. The combination of an ns and an np orbital gives rise to two equivalent sp hybrids oriented at 180°, whereas the combination of an ns and two or three np orbitals produces three equivalent sp2 hybrids or four equivalent sp3 hybrids, respectively. The bonding in molecules with more than an octet of electrons around a central atom can be explained by invoking the participation of one or two (n − 1)d orbitals to give sets of five sp3d or six sp3d2 hybrid orbitals, capable of forming five or six bonds, respectively. The spatial orientation of the hybrid atomic orbitals is consistent with the geometries predicted using the VSEPR model.

Key Takeaway

- Hybridization increases the overlap of bonding orbitals and explains the molecular geometries of many species whose geometry cannot be explained using a VSEPR approach.

Conceptual Problems

-

Arrange sp, sp3, and sp2 in order of increasing strength of the bond formed to a hydrogen atom. Explain your reasoning.

-

What atomic orbitals are combined to form sp3, sp, sp3d2, and sp3d? What is the maximum number of electron-pair bonds that can be formed using each set of hybrid orbitals?

-

Why is it incorrect to say that an atom with sp2 hybridization will form only three bonds? The carbon atom in the carbonate anion is sp2 hybridized. How many bonds to carbon are present in the carbonate ion? Which orbitals on carbon are used to form each bond?

-

If hybridization did not occur, how many bonds would N, O, C, and B form in a neutral molecule, and what would be the approximate molecular geometry?

-

How are hybridization and molecular geometry related? Which has a stronger correlation—molecular geometry and hybridization or Lewis structures and hybridization?

-

In the valence bond approach to bonding in BeF2, which step(s) require(s) an energy input, and which release(s) energy?

-

The energies of hybrid orbitals are intermediate between the energies of the atomic orbitals from which they are formed. Why?

-

How are lone pairs on the central atom treated using hybrid orbitals?

-

Because nitrogen bonds to only three hydrogen atoms in ammonia, why doesn’t the nitrogen atom use sp2 hybrid orbitals instead of sp3 hybrids?

-

Using arguments based on orbital hybridization, explain why the CCl62− ion does not exist.

-

Species such as NF52− and OF42− are unknown. If 3d atomic orbitals were much lower energy, low enough to be involved in hybrid orbital formation, what effect would this have on the stability of such species? Why? What molecular geometry, electron-pair geometry, and hybridization would be expected for each molecule?

Numerical Problems

-

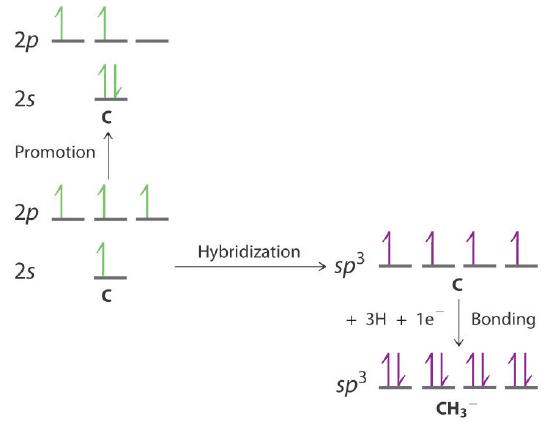

Draw an energy-level diagram showing promotion and hybridization to describe the bonding in CH3−. How does your diagram compare with that for methane? What is the molecular geometry?

-

Draw an energy-level diagram showing promotion and hybridization to describe the bonding in CH3+. How does your diagram compare with that for methane? What is the molecular geometry?

-

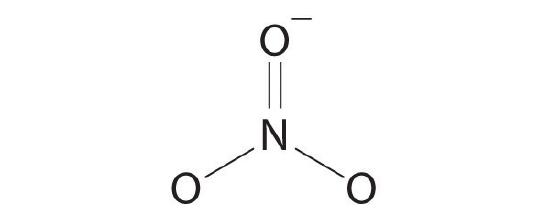

Draw the molecular structure, including any lone pairs on the central atom, state the hybridization of the central atom, and determine the molecular geometry for each molecule.

- BBr3

- PCl3

- NO3−

-

Draw the molecular structure, including any lone pairs on the central atom, state the hybridization of the central atom, and determine the molecular geometry for each species.

- AsBr3

- CF3+

- H2O

-

What is the hybridization of the central atom in each of the following?

- CF4

- CCl22−

- IO3−

- SiH4

-

What is the hybridization of the central atom in each of the following?

- CCl3+

- CBr2O

- CO32−

- IBr2−

-

What is the hybridization of the central atom in PF6−? Is this ion likely to exist? Why or why not? What would be the shape of the molecule?

-

What is the hybridization of the central atom in SF5−? Is this ion likely to exist? Why or why not? What would be the shape of the molecule?

Answers

-

The promotion and hybridization process is exactly the same as shown for CH4 in the chapter. The only difference is that the C atom uses the four singly occupied sp3 hybrid orbitals to form electron-pair bonds with only three H atoms, and an electron is added to the fourth hybrid orbital to give a charge of 1–. The electron-pair geometry is tetrahedral, but the molecular geometry is pyramidal, as in NH3.

-

-

-

The central atoms in CF4, CCl22–, IO3−, and SiH4 are all sp3 hybridized.

-

-

The phosphorus atom in the PF6− ion is sp3d2 hybridized, and the ion is octahedral. The PF6− ion is isoelectronic with SF6 and has essentially the same structure. It should therefore be a stable species.

-

Contributors

- Anonymous

Modified by Joshua Halpern