4.6 Phase Changes

- Page ID

- 163739

We have previously described evaporation, the change of a liquid to a gas. This process is always endothermic, because energy is required to completely disrupt the IMFs of attraction between the particles. The reverse process of evaporation is condensation, which is always an exothermic process because IMFs of attraction form among the particles as they congregate into droplets. The phase changes involving solids are described below.

Sublimation and Deposition

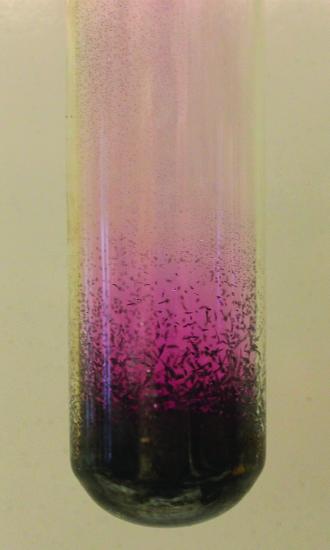

Some solids can transition directly into the gaseous state, bypassing the liquid state, via a process known as sublimation. At room temperature and standard pressure, a piece of dry ice (solid CO2) sublimes, appearing to gradually disappear without ever forming any liquid. Snow and ice sublime at temperatures below the melting point of water, a slow process that may be accelerated by winds and the reduced atmospheric pressures at high altitudes. When solid iodine is warmed, the solid sublimes and a vivid purple vapor forms (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The reverse of sublimation is called deposition, a process in which gaseous substances directly change into the solid state, bypassing the liquid state. The formation of frost is an example of deposition.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Sublimation of solid iodine in the bottom of the tube produces a purple gas that subsequently deposits as solid iodine on the colder part of the tube above. (credit: modification of work by Mark Ott)

Like vaporization, the process of sublimation requires an input of energy to overcome intermolecular attractions. The enthalpy of sublimation, ΔHsub, is the energy required to convert one mole of a substance from the solid to the gaseous state. For example, the sublimation of carbon dioxide is represented by:

\[\ce{CO2}(s)⟶\ce{CO2}(g)\hspace{20px}ΔH_\ce{sub}=\mathrm{26.1\: kJ/mol}\]

Likewise, the enthalpy change for the reverse process of deposition is equal in magnitude but opposite in sign to that for sublimation:

\[\ce{CO2}(g)⟶\ce{CO2}(s)\hspace{20px}ΔH_\ce{dep}=−ΔH_\ce{sub}=\mathrm{−26.1\:kJ/mol}\]

Fusion/Melting and Solidification/Freezing

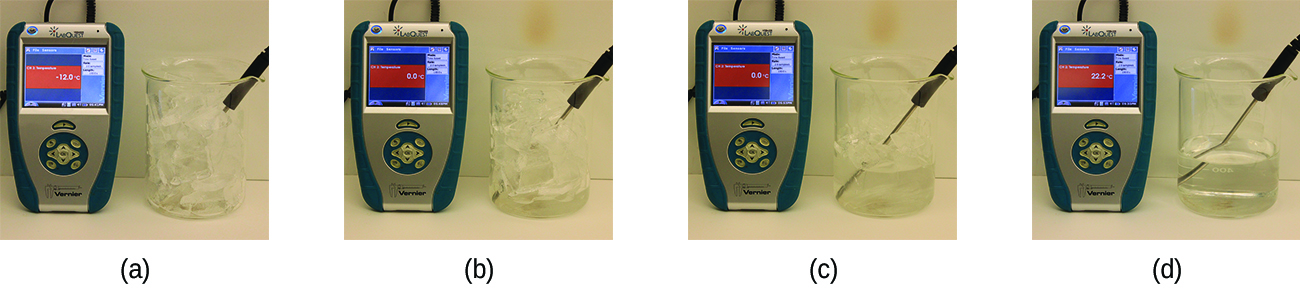

When we heat a crystalline solid, we increase the average energy of its atoms, molecules, or ions and the solid gets hotter. At some point, the added energy becomes large enough to partially overcome the forces holding the molecules or ions of the solid in their fixed positions, and the solid begins the process of transitioning to the liquid state, or melting. At this point, the temperature of the solid stops rising, despite the continual input of heat, and it remains constant until all of the solid is melted. Only after all of the solid has melted will continued heating increase the temperature of the liquid (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): (a) This beaker of ice has a temperature of −12.0 °C. (b) After 10 minutes the ice has absorbed enough heat from the air to warm to 0 °C. A small amount has melted. (c) Thirty minutes later, the ice has absorbed more heat, but its temperature is still 0 °C. The ice melts without changing its temperature. (d) Only after all the ice has melted does the heat absorbed cause the temperature to increase to 22.2 °C. (credit: modification of work by Mark Ott).

If we stop heating during melting and place the mixture of solid and liquid in a perfectly insulated container so no heat can enter or escape, the solid and liquid phases remain in equilibrium. This is almost the situation with a mixture of ice and water in a very good thermos bottle; almost no heat gets in or out, and the mixture of solid ice and liquid water remains for hours. In a mixture of solid and liquid at equilibrium, the reciprocal process of melting and freezing occur at equal rates, and the quantities of solid and liquid therefore remain constant. The temperature at which the solid and liquid phases of a given substance are in equilibrium is called the melting point of the solid or the freezing point of the liquid. Use of one term or the other is normally dictated by the direction of the phase transition being considered, for example, solid to liquid (melting) or liquid to solid (freezing).

The enthalpy of fusion and the melting point of a crystalline solid depend on the strength of the attractive forces between the units present in the crystal. Molecules with weak attractive forces form crystals with low melting points. Crystals consisting of particles with stronger attractive forces melt at higher temperatures.

The amount of heat required to change one mole of a substance from the solid state to the liquid state is the enthalpy of fusion, \(ΔH_{fus}\) of the substance. The enthalpy of fusion of ice is 6.0 kJ/mol at 0 °C. Fusion (melting) is an endothermic process:

\[\ce{H2O}_{(s)} \rightarrow \ce{H2O}_{(l)} \;\; ΔH_\ce{fus}=\mathrm{6.01\; kJ/mol} \label{10.4.9}\]

The reciprocal process, freezing, is an exothermic process whose enthalpy change is −6.0 kJ/mol at 0 °C:

\[\ce{H_2O}_{(l)} \rightarrow \ce{H_2O}_{(s)}\;\; ΔH_\ce{frz}=−ΔH_\ce{fus}=−6.01\;\mathrm{kJ/mol} \label{10.4.10}\]

Selected molar enthalpies of fusion are tabulated in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\). Solids like ice which have strong intermolecular forces have much higher values than those like CH4 with weak ones. Note that the enthalpies of fusion and vaporization change with temperature.

| Substance | Formula | ΔH(fusion) / kJ mol1 |

Melting Point / K | ΔH(vaporization) / kJ mol-1 | Boiling Point / K | (ΔHv/Tb) / JK-1 mol-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neon | Ne | 0.33 | 24 | 1.80 | 27 | 67 |

| Oxygen | O2 | 0.44 | 54 | 6.82 | 90.2 | 76 |

| Methane | CH4 | 0.94 | 90.7 | 8.18 | 112 | 73 |

| Ethane | C2H6 | 2.85 | 90.0 | 14.72 | 184 | 80 |

| Chlorine | Cl2 | 6.40 | 172.2 | 20.41 | 239 | 85 |

| Carbon tetrachloride | CCl4 | 2.67 | 250.0 | 30.00 | 350 | 86 |

| Water* | H2O | 6.00678 at 0°C, 101kPa 6.354 at 81.6 °C, 2.50 MPa |

273.1 | 40.657 at 100 °C, 45.051 at 0 °C, 46.567 at -33 °C |

373.1 | 109 |

| n-Nonane | C9H20 | 19.3 | 353 | 40.5 | 491 | 82 |

| Mercury | Hg | 2.30 | 234 | 58.6 | 630 | 91 |

| Sodium | Na | 2.60 | 371 | 98 | 1158 | 85 |

| Aluminum | Al | 10.9 | 933 | 284 | 2600 | 109 |

| Lead | Pb | 4.77 | 601 | 178 | 2022 | 88 |

Energy Changes Associated with Phase Changes

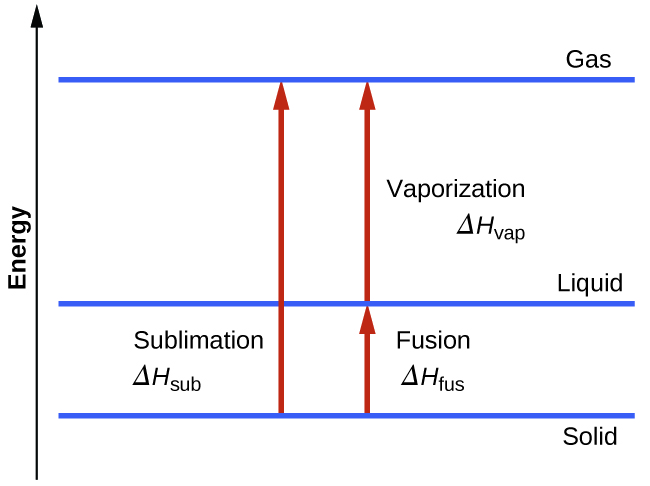

Consider the extent to which intermolecular attractions must be overcome to achieve a given phase transition. Converting a solid into a liquid requires that these attractions be only partially overcome; transition to the gaseous state requires that they be completely overcome. As a result, the enthalpy of fusion for a substance is less than its enthalpy of vaporization. This same logic can be used to derive an approximate relation between the enthalpies of all phase changes for a given substance. Though not an entirely accurate description, sublimation may be conveniently modeled as a sequential two-step process of melting followed by vaporization in order to apply Hess’s Law.

\[\mathrm{solid⟶liquid}\hspace{20px}ΔH_\ce{fus}\\\underline{\mathrm{liquid⟶gas}\hspace{20px}ΔH_\ce{vap}}\\\mathrm{solid⟶gas}\hspace{20px}ΔH_\ce{sub}=ΔH_\ce{fus}+ΔH_\ce{vap}\]

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): For a given substance, the sum of its enthalpy of fusion and enthalpy of vaporization is approximately equal to its enthalpy of sublimation.

Contributors

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).