4.2: Understanding Atomic Spectra

- Page ID

- 85153

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Differentiate between a continuous and discontinuous spectrum

- Classify all types of radiation as being ionizing or nonionizing.

- Understand that ionizing radiation can knock electrons off DNA.

- Know that radiation of short wavelength is toxic.

- Understand the processes of absorption and emission.

- Explain the science behind fireworks.

- Realize that chemists and other scientists use AA/AE in quantitative and qualitative analyses

Continuous Spectrum

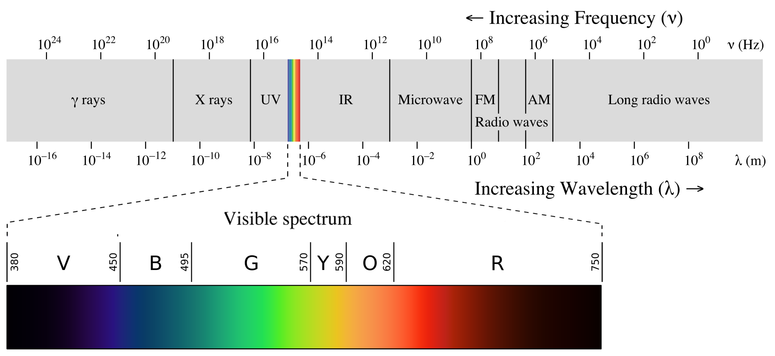

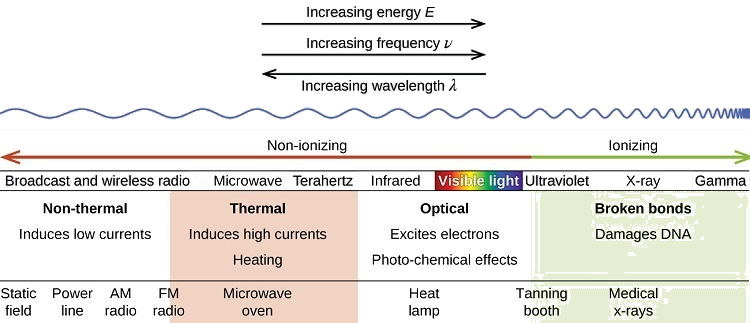

A rainbow is an example of a continuous spectrum. Here, the colors displayed are within the visible spectrum (between 380-760 nm). Light in this wavelength range is visible to the naked eye. Unlike the visible spectrum, light that is of different wavelengths (see the electromagnetic spectrum below) is not visible. Looking at Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), note the different areas of the light (or electromagnetic spectrum). Areas of light that possess short wavelengths are located on the left of the spectrum. All wavelengths from UV (ultraviolet) to \(γ\) (gamma) range have the potential to ionize tissues and/or DNA. As a result, individuals who have been exposed to large amounts of these types of radiation in acute time periods could develop cancer. In contrast, visible light (see the rainbow area in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) and radiation on the right side of the spectrum has longer wavelengths and does not have the potential to ionize tissues and/or DNA. Visible, infrared (labeled IR), microwave, and radio waves are classified as being nonionizing radiation and have not been linked to cancer.

Please be aware of what types of light are ionizing and nonionizing. Do not memorize the wavelengths or frequencies of the electromagnetic spectrum. It is important that you know that the electromagnetic spectrum is an example of a continuous spectrum.

For each section of the electromagnetic spectrum, be sure to know a source or application of each type (example for radio waves would be cell phones). Also, also have a good understanding of how the UV portion can be expanded. Review UV information, by clicking on this link. Please do not memorize the ABCDE's of cancer nor the types of skin cancer that occur.

Atomic Emission Spectra

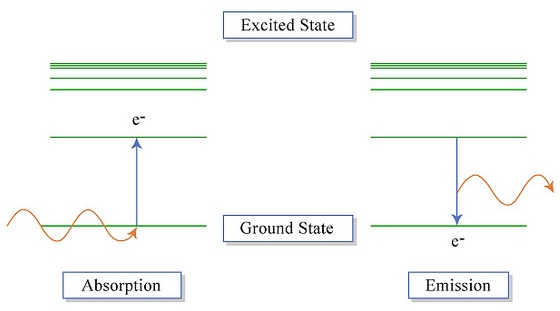

The electrons in an atom tend to be arranged in such a way that the energy of the atom is as low as possible. The ground state of an atom is the lowest energy state of the atom. When those atoms are given energy, the electrons absorb the energy and move to a higher energy level. These energy levels of the electrons in atoms are quantized, meaning again that the electron must move from one energy level to another in discrete steps rather than continuously. An excited state of an atom is a state where its potential energy is higher than the ground state. An atom in the excited state is not stable. When it returns back to the ground state (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)), it releases the energy that it had previously gained often in the form of electromagnetic radiation (although it can be released via heat).

Atoms can gain energy to induce these transitions from various sources. The gases in the image below have been excited with the use of electrical current. The atoms in each of these noble gases produce distinctive colors that can be used to identify the elements (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Each of these species contains a different number of electrons that can undergo different types of excitations. In turn, each gas produces a signature color.

Flames can be utilized to excite atoms as well. During a flame test experiment, metal chlorides are directly placed into a flame. The intense heat will promote the metal's electrons to an excited state. Upon emission, this extra energy is released in the form of visible light. If a reference panel is provided, the flame color can be used to identify a metal atom (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

| Metal Ion | Flame Color | Metal Ion | Flame Color | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li | Red | K | Light Purple | |

| Na | Orange | Ba | Light Green | |

| Ca | Orange-Red | Cu | Blue | |

| Sr | Red |

Fireworks are similar to flame test experiments. Firework manufacturers select certain metal atoms to produce desired colors for these devices. Individual detonators will explode the metal compounds to emit radiant colors of light. Watch the video below to see the largest aerial firework shell explode over the United Arab Emirates on December 31, 2017. While watching the video, compare the colors you see to the chart above to identify the atoms that were used in the display.

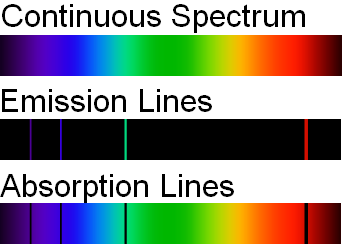

Discontinous Spectra

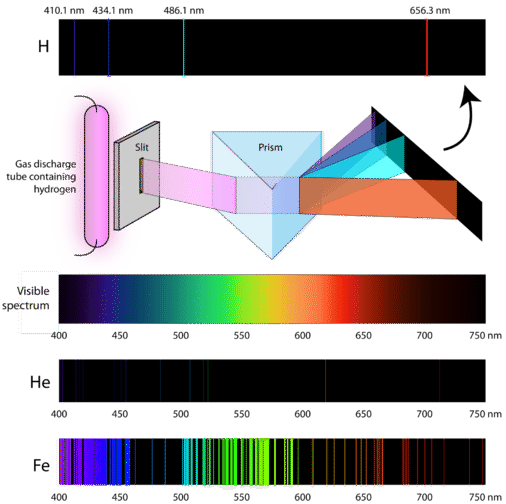

If the light emitted from the excited atoms is viewed through a prism, then individual patterns of lines will be produced. These lines are called spectra and correspond to fingerprint wavelengths (symbol for wavelength is \(\lambda\)) for a specific element. Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\) illustrates how the light from excited electrons can be diffracted to produce line spectra for the elements of hydrogen, helium, and iron. The specific elements produce wavelengths within the visible spectrum (between 400-700 nm) and can be seen by the naked eye. In order to obtain the numerical wavelengths (in nanometers), one would need to employ some type of detector.

Atomic Absorption Spectra

In addition to emission studies, chemists will also use atomic absorption to identify and quantify. Noting the energy changes from ground to excited states, chemists can obtain another type of discontinuous spectrum (see image below). Once again, a fingerprint wavelength pattern is produced that can be used to identify an atom. Academia and Industry could employ either an AA (atomic absorption) or AE (atomic emission) spectrometer to analyze the atoms within a sample.

Which statements is/are true?

- Microwaves can give you cancer.

- When exploding fireworks, you will see the color when the metal atoms absorb energy from the detonater.

- When using an AA or an AE spectrometer, a scientist will obtain a line spectra, not continuous spectra.

- The flame test gives specific colors for metal atoms.

- Gamma rays are ionizing and can cause cancer.

- In the light spectrum, you can see IR and visible with only your eyes.

- Continuous spectra can be used to identify an atom.

- Answer a

-

False, they do not possess enough energy to knock electrons off tissues or DNA

- Answer b

-

False, the color is given off during the emission or falling back process.

- Answer c

-

True, scientists need those fingerprint wavelengths to identify atoms.

- Answer d

-

True, the metals are the species that become excited and eventually emit the visible light.

- Answer e

-

True, ultraviolet, gamma, and x-ray are powerful forms of radiation that can cause cancer.

- Answer f

-

False, you can only see images in the visible spectrum (people who are colorblind are even more limited).

- Answer g

-

False, chemists need those specific wavelengths to identify atoms, not a spectrum that shows a continuous flow of wavelengths.

Summary

Atomic emission spectra are produced when excited electrons return to the ground state.

- When electrons return to a lower energy level, they emit energy in the form of light.

- Bohr's model suggests each atom has a set of unchangeable energy levels and electrons in the electron cloud of that atom must be in one of those energy levels.

- Bohr's model suggests that the atomic spectra of atoms are produced by electrons gaining energy from some source, jumping up to a higher energy level, then immediately dropping back to a lower energy level and emitting the energy difference between the two energy levels.

- The existence of the atomic spectra is support for Bohr's model of the atom.

- Bohr's model was only successful in calculating energy levels for the hydrogen atom.

- The emitted light corresponds to energies of the specific electrons.

Vocabulary

- Emission spectrum (or atomic spectrum): The unique pattern of light given off by an element when it is given energy

- Ground state: to be in the lowest energy level possible.

- Excited state: to be in a higher energy level.

Contributors and Attributions

Isabella Quiros (Furman University)