5.6: Measuring Radiation

- Page ID

- 92223

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Define units for measuring radiation exposure

- Explain the operation of common tools for detecting radioactivity

- List common sources of radiation exposure in the United States

- Calculate rem, Sv, mrem, and µSv and compare them to the reference standards.

- Remember average background of yearly radiation is 360 mrem.

- the View radiation video at bottom of the page and identify who receives the most ionizing radiation per year.

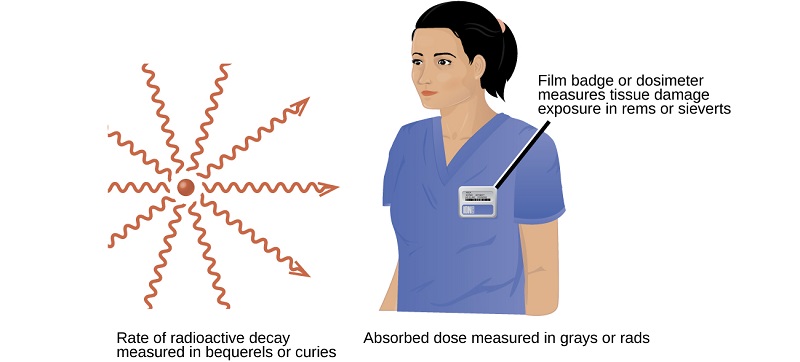

Several different devices are used to detect and measure radiation, including Geiger counters, scintillation counters (scintillators), and radiation dosimeters (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Probably the best-known radiation instrument, the Geiger counter (also called the Geiger-Müller counter) detects and measures radiation. Radiation causes the ionization of the gas in a Geiger-Müller tube. The rate of ionization is proportional to the amount of radiation. These types of devices measure alpha and beta radiation quite well. If a Geiger counter is altered, it can detect gamma and x-rays. A scintillation counter contains a scintillator (a material that emits light (luminesces) when excited by ionizing radiation) and a sensor that converts the light into an electric signal. This instrument can effectively detect gamma, x-rays and, beta particles. Radiation dosimeters also measure ionizing radiation and are often used to determine personal radiation exposure. Commonly used types are electronic, film badge, thermoluminescent, and quartz fiber dosimeters.

A variety of units are used to measure different aspects of radiation (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The becquerel (Bq), and the curie (Ci) are used to describe rate of radioactive decay. Named in honor of Henri Becquerel and the the Curies, these units do not describe the damaging effects of radiation. Early medical applications used the units of of rad or gray (Gy) to indicate energy emitted onto an absorbing material. Today, most industries rely on the sievert (Sv) or rem. These two units measure tissue damage caused by radiation. Looking at the chart below, please note the different units and what they describe. In CHM 101, it is not necessary for you to perform conversions (with the exception of rem/sV) with units that involve activities or absorbed doses.

| Measurement Purpose | Unit | Quantity Measured | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| activity of source | becquerel (Bq) | radioactive decays or emissions | amount of sample that undergoes 1 decay/second |

| curie (Ci) |

amount of sample that undergoes \(\mathrm{3.7 \times 10^{10}\; decays/second}\). The body normally contains .1\(\mu\)Ci of C-14 radiation. 1 Ci is a huge amount of radiation. |

||

| absorbed dose | gray (Gy) | energy absorbed per kg of tissue | 1 Gy = 1 J/kg tissue |

| radiation absorbed dose (rad) |

1 rad = 0.01 J/kg tissue Acute radiation sickness occurs before 100 rad. |

||

| biologically effective dose | sievert (Sv) | tissue damage | Sv = RBE × Gy |

| roentgen equivalent for man (rem) |

Rem = RBE × rad An average American is exposed to around 360 mrem of radiation/yr. Acute radiation poisoning can occur at levels as low as 25 rems. Chernobyl liquidators were exposed to between 7.5x105 and 1.3x106 mrems of radiation. |

The roentgen equivalent for man (rem) is the unit for radiation damage that is used most frequently in medicine (100 rem = 1 Sv). For testing or therapy, radiation values will typically be given in mrem (millirem) or mSv (millisievert). Knowing how to convert these units will enable you to compare them to given standards. In addition, understanding the exposure limits in mrem, mSv, Sv, and uSv can give you an idea of the level of toxicity involved in nuclear reactor accidents or nuclear weapons.

Effects of Long-term Radiation Exposure on the Human Body

It is impossible to avoid some exposure to ionizing radiation. We are constantly exposed to background radiation from a variety of natural sources, including cosmic radiation, rocks, medical procedures, consumer products, and even our own atoms. We can minimize our exposure by blocking or shielding the radiation, moving farther from the source, and limiting the time of exposure.

As shown in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\), the average person is exposed to background radiation from a variety of sources. Radon gas represents the greatest source of ionizing radiation. Indoor exposure to this alpha ( \(\alpha \)) emitter could increase the likelihood of developing lung cancer.

| Source | Amount (mrem) |

|---|---|

| radon gas | 200 |

| medical sources | 53 |

| radioactive atoms in the body naturally | 39 |

| terrestrial sources (soil) | 28 |

| cosmic sources | 28 |

| consumer products | 10 |

| nuclear energy | 0.05 |

| Total | 358 |

Flying from New York City to San Francisco adds 5 mrem (or 0.005 rem) to your overall radiation exposure because the plane flies above much of the atmosphere, which protects us from most cosmic radiation.

The actual effects of radioactivity and radiation exposure on a person’s health depend on the type of radioactivity, the length of exposure, and the tissues exposed. Table \(\PageIndex{3}\) lists the potential threats to health at various amounts of exposure over short periods of time (hours or days). An average person receives around 400 mrems of radiation each year. This amount is equivalent to 0.400 rems and 4 mSV. Table \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows the acute toxicity level of radiation in the unit rem. Comparing yearly radiation to this table, one can get an idea of how low daily exposure levels are. Additionally, one can understand the radioactive exposure of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Studies involving these groups of people show once exposure limits exceed 100 rem, it is most likely a person will develop some form of cancer.

| Exposure (rem) | Effect |

|---|---|

| 1 (over a full year) | No detectable effect |

| ∼20 | Increased risk of some cancers |

| ∼100 | Damage to bone marrow and other tissues; possible internal bleeding; decrease in white blood cell count |

| 200–300 | Visible “burns” on skin, nausea, vomiting, and fatigue |

| >300 | Loss of white blood cells; hair loss |

| ∼600 | Death |

This 11 minute video shows how radiation can be measured. In addition, the scientists report their findings with various radiation units. While watching the video, answer the questions below to gain a better understanding of radiation around the world.

| Substance or Location | Amount of Radiation in μSv/hr |

|---|---|

| Banana | |

| Range of background radiation | |

| Hiroshima today (event: ___________) | |

| Uranium mine | |

| Trinity Site (event: _____________) | |

| Range of radiation while flying | |

| Chernobyl (event: ___________) | |

| Walking in Fukushima (event: ____________) | |

| Pripyat, Ukraine hospital maximum reading | |

| CT Scan | |

| Fukushima resident (lifetime exposure) | |

| Astronaut | |

| Smoker |

1.Does a Geiger counter measure nonionizing radiation?

2.At an acute level, how many Sieverts (Sv) of radiation will kill a person?

3. Fill in the missing information of the chart above (events and values):

- What two places in Marie Curie's lab are still radioactive? What type of radiation is still lingering?

- Why did the residents of Chernobyl and Fukushima have black bags on the sides of their highways?

- In this video, what individuals are exposed to the most radiation in μSv?

References

- 1 Source: US Environmental Protection Agency

Contributors

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).

- Emma Gibney (Furman University)