3.5.1: Molecular Shape and Polarity

- Page ID

- 210718

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Explain the concepts of polar covalent bonds and molecular polarity

- Assess the polarity of a molecule based on its bonding and structure

Molecular Polarity and Dipole Moment

As discussed previously, polar covalent bonds connect two atoms with differing electronegativities, leaving one atom with a partial positive charge (δ+) and the other atom with a partial negative charge (δ–), as the electrons are pulled toward the more electronegative atom. This separation of charge gives rise to a bond dipole moment. The magnitude of a bond dipole moment is represented by the Greek letter mu (µ) and is given by

\[μ=Qr \label{7.6.X}\]

where

- \(Q\) is the magnitude of the partial charges (determined by the electronegativity difference) and

- \(r\) is the distance between the charges:

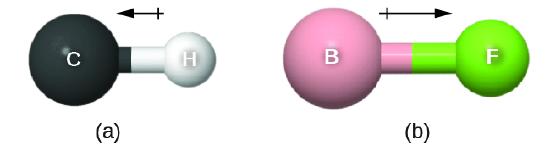

This bond moment can be represented as a vector, a quantity having both direction and magnitude (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Dipole vectors are shown as arrows pointing along the bond from the less electronegative atom toward the more electronegative atom. A small plus sign is drawn on the less electronegative end to indicate the partially positive end of the bond. The length of the arrow is proportional to the magnitude of the electronegativity difference between the two atoms.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): (a) There is a small difference in electronegativity between C and H, represented as a short vector. (b) The electronegativity difference between B and F is much larger, so the vector representing the bond moment is much longer.

A whole molecule may also have a separation of charge, depending on its molecular structure and the polarity of each of its bonds. If such a charge separation exists, the molecule is said to be a polar molecule (or dipole); otherwise the molecule is said to be nonpolar. The dipole moment measures the extent of net charge separation in the molecule as a whole. We determine the dipole moment by adding the bond moments in three-dimensional space, taking into account the molecular structure.

For diatomic molecules, there is only one bond, so its bond dipole moment determines the molecular polarity. Homonuclear diatomic molecules such as Br2 and N2 have no difference in electronegativity, so their dipole moment is zero. For heteronuclear molecules such as CO, there is a small dipole moment. For HF, there is a larger dipole moment because there is a larger difference in electronegativity.

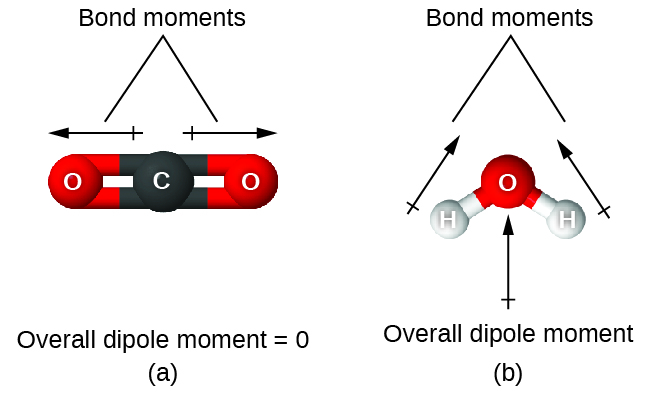

When a molecule contains more than one bond, the geometry must be taken into account. If the bonds in a molecule are arranged such that their bond moments cancel (vector sum equals zero), then the molecule is nonpolar. This is the situation in CO2 (Figure \(\PageIndex{2A}\)). Each of the bonds is polar, but the molecule as a whole is nonpolar. From the Lewis structure, and using VSEPR theory, we determine that the CO2 molecule is linear with polar C=O bonds on opposite sides of the carbon atom. The bond moments cancel because they are pointed in opposite directions. In the case of the water molecule (Figure \(\PageIndex{2B}\)), the Lewis structure again shows that there are two bonds to a central atom, and the electronegativity difference again shows that each of these bonds has a nonzero bond moment. In this case, however, the molecular structure is bent because of the lone pairs on O, and the two bond moments do not cancel. Therefore, water does have a net dipole moment and is a polar molecule (dipole).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): The overall dipole moment of a molecule depends on the individual bond dipole moments and how they are arranged. (a) Each CO bond has a bond dipole moment, but they point in opposite directions so that the net CO2 molecule is nonpolar. (b) In contrast, water is polar because the OH bond moments do not cancel out.

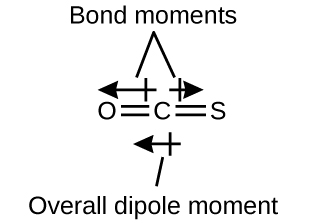

The OCS molecule has a structure similar to CO2, but a sulfur atom has replaced one of the oxygen atoms. To determine if this molecule is polar, we draw the molecular structure. VSEPR theory predicts a linear molecule:

The C–O bond is considerably polar. Although C and S have very similar electronegativity values, S is slightly more electronegative than C, and so the C-S bond is just slightly polar. Because oxygen is more electronegative than sulfur, the oxygen end of the molecule is the negative end.

Chloromethane, CH3Cl, is another example of a polar molecule. Although the polar C–Cl and C–H bonds are arranged in a tetrahedral geometry, the C–Cl bonds have a larger bond moment than the C–H bond, and the bond moments do not completely cancel each other. All of the dipoles have a upward component in the orientation shown, since carbon is more electronegative than hydrogen and less electronegative than chlorine:

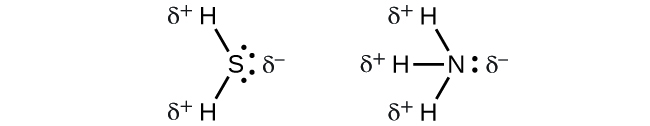

When we examine the highly symmetrical molecules BF3 (trigonal planar), CH4 (tetrahedral), PF5 (trigonal bipyramidal), and SF6 (octahedral), in which all the polar bonds are identical, the molecules are nonpolar. The bonds in these molecules are arranged such that their dipoles cancel. However, just because a molecule contains identical bonds does not mean that the dipoles will always cancel. Many molecules that have identical bonds and lone pairs on the central atoms have bond dipoles that do not cancel. Examples include H2S and NH3. A hydrogen atom is at the positive end and a nitrogen or sulfur atom is at the negative end of the polar bonds in these molecules:

To summarize, to be polar, a molecule must:

- Contain at least one polar covalent bond.

- Have a molecular structure such that the sum of the vectors of each bond dipole moment does not cancel.

Properties of Polar Molecules

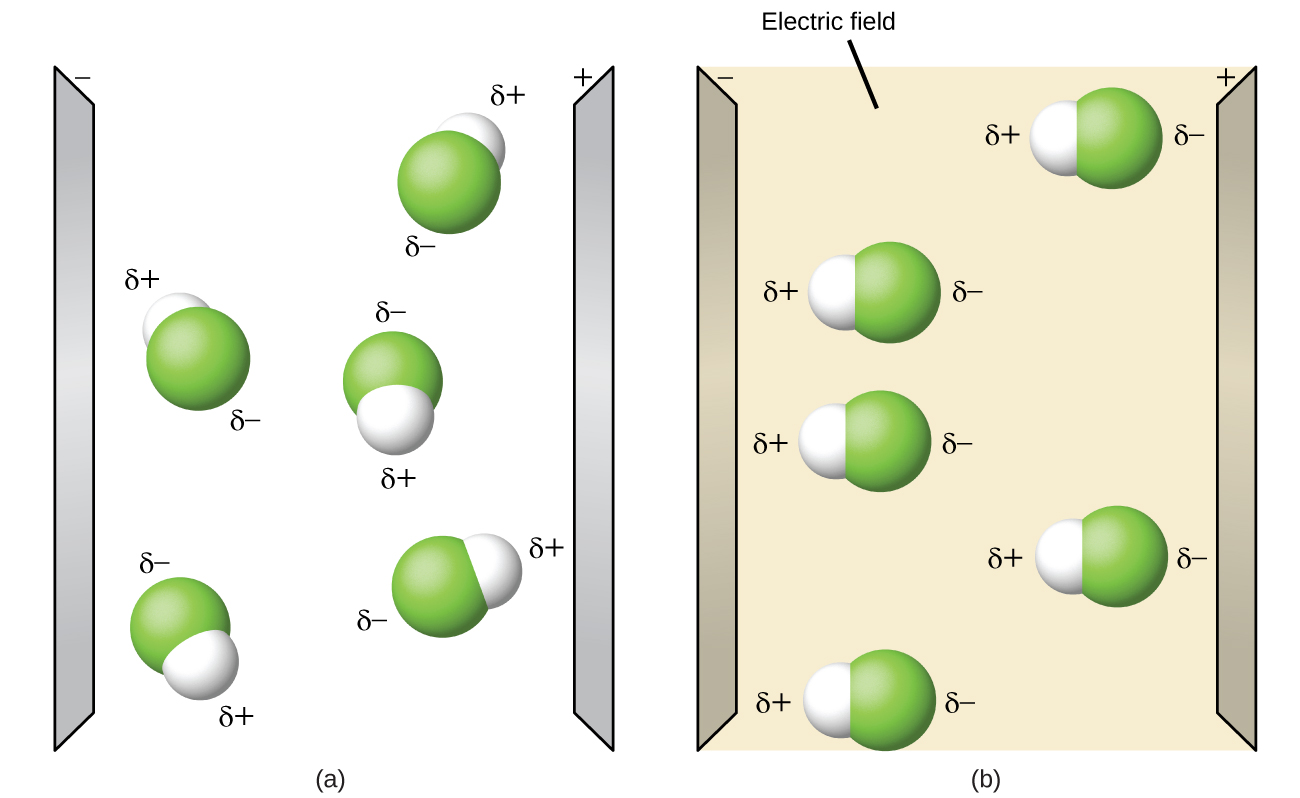

Polar molecules tend to align when placed in an electric field with the positive end of the molecule oriented toward the negative plate and the negative end toward the positive plate (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). We can use an electrically charged object to attract polar molecules, but nonpolar molecules are not attracted. Also, polar solvents are better at dissolving polar substances, and nonpolar solvents are better at dissolving nonpolar substances.

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\): (a) Molecules are always randomly distributed in the liquid state in the absence of an electric field. (b) When an electric field is applied, polar molecules like HF will align to the dipoles with the field direction.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Polarity Simulations

Open the molecule polarity simulation and select the “Three Atoms” tab at the top. This should display a molecule ABC with three electronegativity adjustors. You can display or hide the bond moments, molecular dipoles, and partial charges at the right. Turning on the Electric Field will show whether the molecule moves when exposed to a field, similar to Figure \(\PageIndex{14}\).

Use the electronegativity controls to determine how the molecular dipole will look for the starting bent molecule if:

- A and C are very electronegative and B is in the middle of the range.

- A is very electronegative, and B and C are not.

Solution

- Molecular dipole moment points immediately between A and C.

- Molecular dipole moment points along the A–B bond, toward A.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Determine the partial charges that will give the largest possible bond dipoles.

- Answer

-

The largest bond moments will occur with the largest partial charges. The two solutions above represent how unevenly the electrons are shared in the bond. The bond moments will be maximized when the electronegativity difference is greatest. The controls for A and C should be set to one extreme, and B should be set to the opposite extreme. Although the magnitude of the bond moment will not change based on whether B is the most electronegative or the least, the direction of the bond moment will.

Summary

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): An overview of polarity and molecular shape.

A dipole moment measures a separation of charge. For one bond, the bond dipole moment is determined by the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms. For a molecule, the overall dipole moment is determined by both the individual bond moments and how these dipoles are arranged in the molecular structure. Polar molecules (those with an appreciable dipole moment) interact with electric fields, whereas nonpolar molecules do not.

Glossary

- axial position

- location in a trigonal bipyramidal geometry in which there is another atom at a 180° angle and the equatorial positions are at a 90° angle

- bond angle

- angle between any two covalent bonds that share a common atom

- bond distance

- (also, bond length) distance between the nuclei of two bonded atoms

- bond dipole moment

- separation of charge in a bond that depends on the difference in electronegativity and the bond distance represented by partial charges or a vector

- dipole moment

- property of a molecule that describes the separation of charge determined by the sum of the individual bond moments based on the molecular structure

- electron-pair geometry

- arrangement around a central atom of all regions of electron density (bonds, lone pairs, or unpaired electrons)

- equatorial position

- one of the three positions in a trigonal bipyramidal geometry with 120° angles between them; the axial positions are located at a 90° angle

- linear

- shape in which two outside groups are placed on opposite sides of a central atom

- molecular structure

- structure that includes only the placement of the atoms in the molecule

- octahedral

- shape in which six outside groups are placed around a central atom such that a three-dimensional shape is generated with four groups forming a square and the other two forming the apex of two pyramids, one above and one below the square plane

- polar molecule

- (also, dipole) molecule with an overall dipole moment

- tetrahedral

- shape in which four outside groups are placed around a central atom such that a three-dimensional shape is generated with four corners and 109.5° angles between each pair and the central atom

- trigonal bipyramidal

- shape in which five outside groups are placed around a central atom such that three form a flat triangle with 120° angles between each pair and the central atom, and the other two form the apex of two pyramids, one above and one below the triangular plane

- trigonal planar

- shape in which three outside groups are placed in a flat triangle around a central atom with 120° angles between each pair and the central atom

- valence shell electron-pair repulsion theory (VSEPR)

- theory used to predict the bond angles in a molecule based on positioning regions of high electron density as far apart as possible to minimize electrostatic repulsion

- vector

- quantity having magnitude and direction

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).

- Adelaide Clark, Oregon Institute of Technology

- Crash Course Chemistry: Crash Course is a division of Complexly and videos are free to stream for educational purposes.