Heat of Sublimation

- Page ID

- 1939

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The molar heat (or enthalpy) of sublimation is the amount of energy that must be added to a mole of solid at constant pressure to turn it directly into a gas (without passing through the liquid phase). Sublimation requires all the forces are broken between the molecules (or other species, such as ions) in the solid as the solid is converted into a gas. The heat of sublimation is generally expressed as \(\Delta H_{sub}\) in units of Joules per mole or kilogram of substance.

Introduction

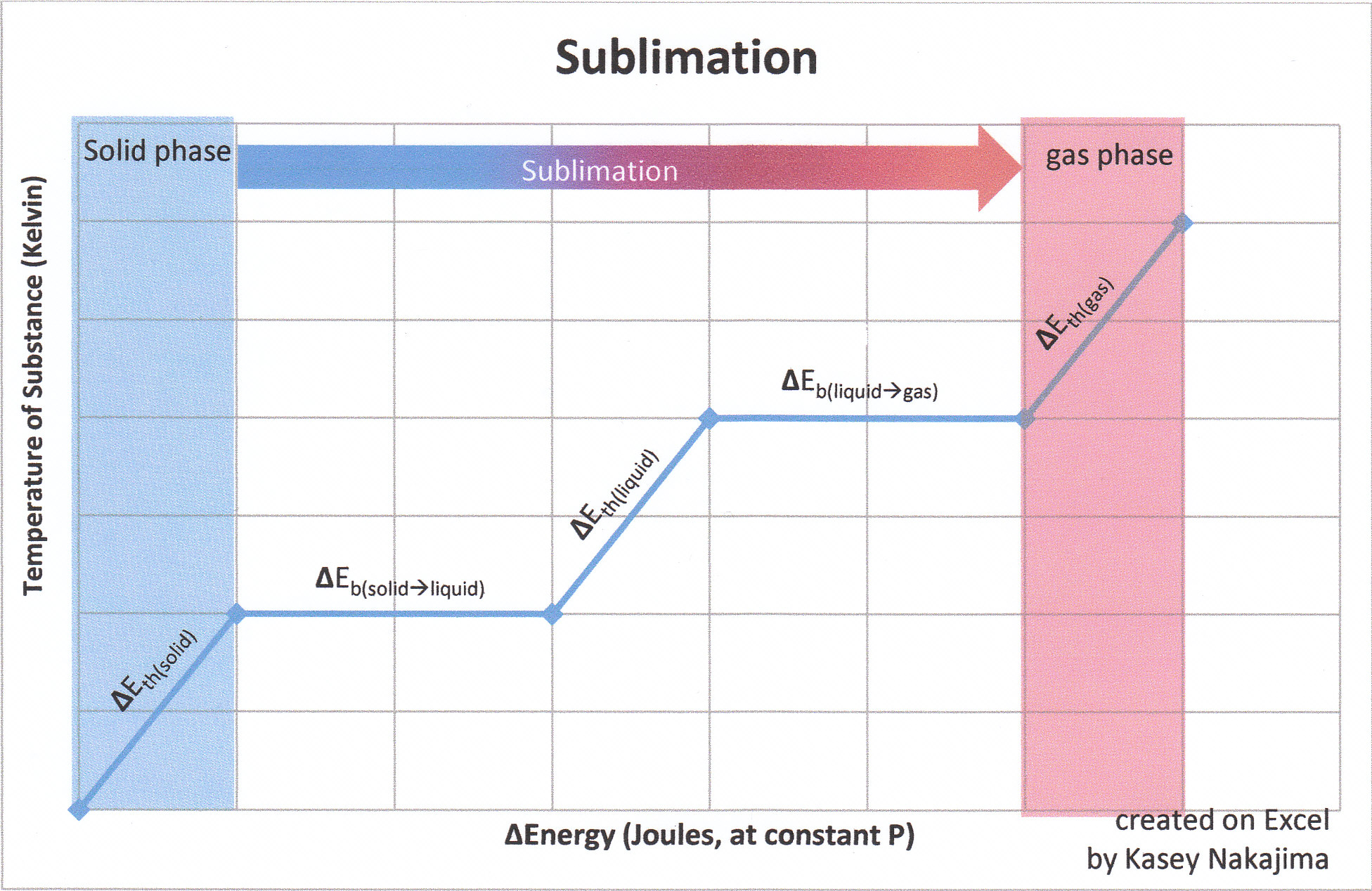

Sublimation is the process of changing a solid into a gas without passing through the liquid phase. To sublime a substance, a certain energy must be transferred to the substance via heat (q) or work (w). The energy needed to sublime a substance is particular to the substance's identity and temperature and must be sufficient to do all of the following:

- Excite the solid substance so that it reaches its maximum heat (energy) capacity (q) in the solid state.

- Sever all the intermolecular interactions holding the solid substance together

- Excite the unbonded atoms of the substance so that it reaches its minimum heat capacity in the gaseous state

Decomposing \(\Delta H_{sub}\)

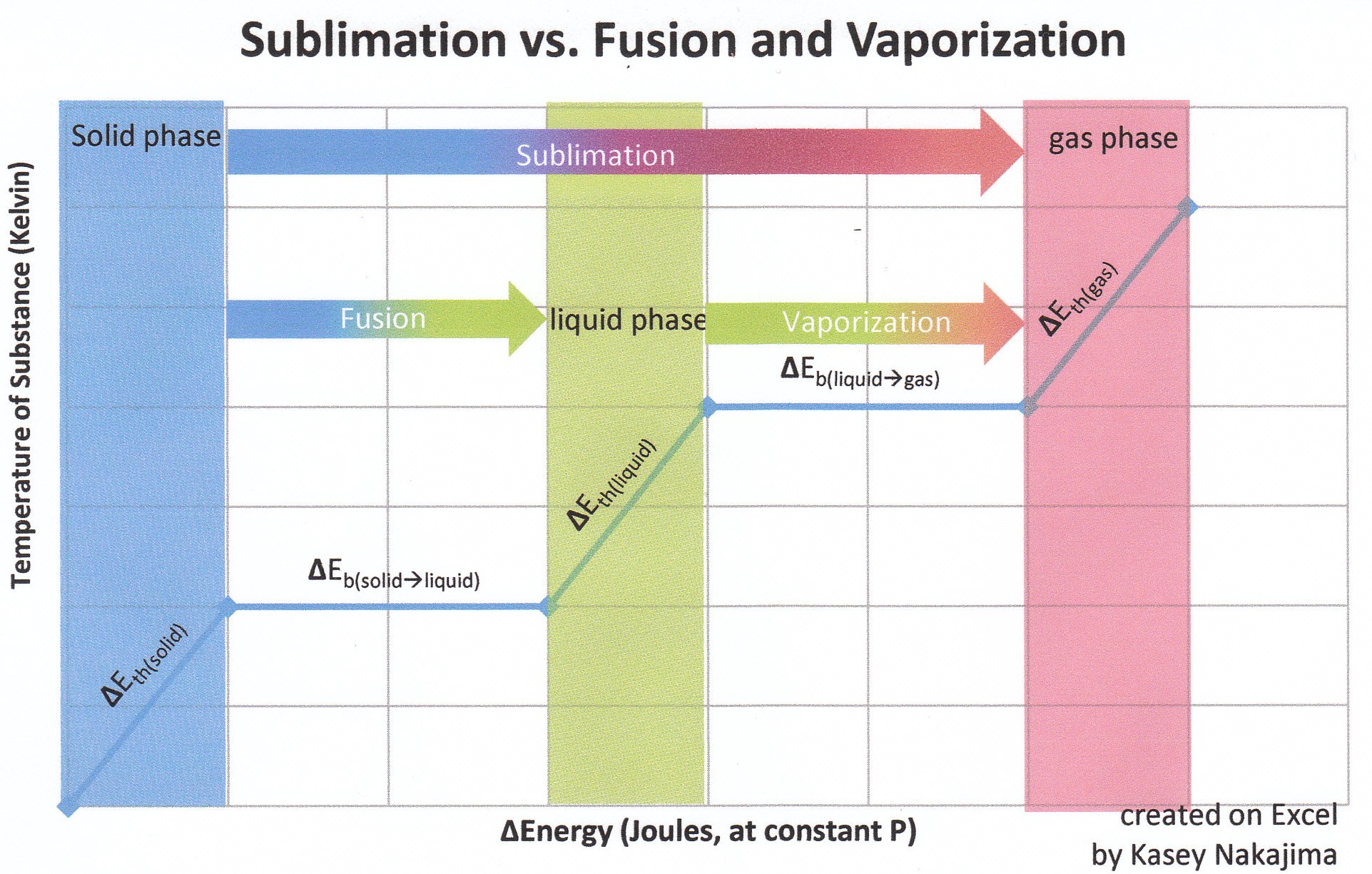

Although the process of sublimation does not involve a solid evolving through the liquid phase, the fact that enthalpy is a state function allows us to construct a "thermodynamic cycle" and add the various energies associated with the solid, liquid, and gas phases together (e.g., Hess' Law).

The energies involved in sublimation can be expressed by the sum of the enthalpy changes for each step:

\(\Delta H_{sub} = \Delta E_{therm_{s}} + \Delta E_{bond_{solid \rightarrow liquid}} +\Delta E_{therm_{solid}}+\Delta E_{bond_{l \rightarrow \, g}}\)

Recall that for state functions, only the initial and final states of the substance are important. Say for example that state A is the initial state and state B is the final state. How a substance goes from state A to state B does not matter so much as what state A and what state B are. Concerning the state function of enthalpy, the energies associated with enthalpies (whose associated states of matter are contiguous to one another) are additive. Though in sublimation a solid does not pass through the liquid phase on its way to the gas phase, it takes the same amount of energy that it would to first melt (fuse) and then vaporize.

ΔEthermal (state of matter)

A change in thermal energy is indicated by a change in temperature (in Kelvin) of a substance at any particular state of matter. Change in thermal energy is expressed by the equation

\(\Delta E_{therm}=C_p \times \Delta T\)

with

- \(C_p=\text{heat capacity} _{\text{(of a particular state of matter)}}\)

- \(\Delta T = T_{(final)}-T_{(initial)}\)

For more information on heat capacity and specific heat capacity, see heat capacity.

ΔEbond (going from state 1 to state 2)

Bond energy is the amount of energy that a group of atoms must absorb so that it can undergo a phase change (going from a state of lower energy to a state of higher energy). It is measured

\(\Delta E_{bond}=\Delta H_{substance_{\text{phase change}}}*\Delta mass_{(substance)}\)

in which \(\Delta H_{substance_{phase change}}\) is the enthalpy associated with a specific substance at a specific phase change. Common types of enthalpies include the heat of fusion (melting) and the heat of vaporization. Recall that fusion is the phase change that occurs between the solid state and the liquid state, and vaporization is the phase change that occurs between the liquid state and the gas state. Note that if the substance has more than type of intramolecular force holding the solid together, then the substance must absorb enough energy to break all the different types of intermolecular forces before the substance can sublime.

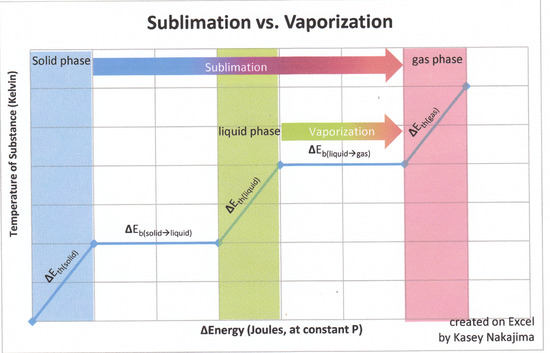

\(\Delta H_{sub}\) is always greater than \(\Delta H_{vap}\)

Vaporization is the transfer of molecules of a substance from the liquid phase to the gas phase. Sublimation is the transfer of molecules from the solid phase to the gas phase. The solid phase is at a lower energy than the liquid phase: that is why substances always release heat when freezing, hence \(\Delta E_{fus \, (s \rightarrow l)} > 0\). Hence, although both sublimation and evaporation involve changing a substance into its gaseous state, the enthalpy change associated with sublimation is always greater than that of vaporization. This is because solid have less energy than those of a liquid, meaning it is takes more energy to excite a solid to its gaseous phase than it does to excite a liquid to its gaseous phase.

Another way to look this phenomena is to take a look at the different energies involved with the heat of sublimation:

- \(\Delta E_{therm\, (s)} \)

- \(\Delta E_{fus \, (s \rightarrow l)}\)

- \(\Delta E_{therm \, (l)}\) and

- \(\Delta E_{vap \, (l\rightarrow g) }\)

Already we know that ΔEbond=ΔH(phase change)*Δm(changed substance) and ΔEbond(l-g)=ΔH(l-g)*Δm(gas created). Hence, \(\Delta E_{vap \, (l\rightarrow g) }\) is actually one component of \(\Delta H_{sub}\).

Consider the sublimation of ice:

\[H_2O_{(s)} \rightarrow H_2O_{(g)}\]

Sublimation can be decomposed involve two steps (assuming no change of temperature, i.e., no heat capacity issues):

- Step 1: The melting of solid water to generate liquid water

\[H_2O_{(s)} \rightarrow H_2O_{(l)}\]

- Step 2: The evaporation of liquid water to generate gaseous water

\[H_2O_{(l)} \rightarrow H_2O_{(g)}\]

The enthalpy change of Step 1 is the molar heat of fusion, \(\Delta H_{fus}\) and the enthalpy change of Step 2 is the molar heat of vaporization, \(\Delta H_{vap}\). Combining these two equations and canceling out anything that appears on both sides of the equation (i.e., liquid water), we're back to the sublimation equation:

Step 1 + Step 2 = Sublimation

Therefore the heat of sublimation, \( \Delta H_{sub}\) is equal to the sum of the heats of fusion and vaporization:

\[ \Delta H_{fus} + \Delta H_{vap} = \Delta H_{sub}\]

Hence, unless \(\Delta H_{fus}\) is equal to or less than zero (which it NEVER is), \(\Delta H_{sub}\) must be greater than \( \Delta H_{vap}\).

Where does the added energy go?

Energy can be observed in many different ways. As shown above, ΔEtot can be expressed as ΔEthermal + ΔEbond. Another way in which ΔEtot can be expressed is change in potential energy, ΔPE, plus change in kinetic energy, ΔKE. Potential energy is the energy associated with random movement, whereas kinetic energy is the energy associated with velocity (movement with direction). ΔEtot = ΔEthermal + ΔEbond and ΔEtot = ΔPE + ΔKE are related by the equations

ΔPE = (0.5)ΔEthermal + ΔEbond

ΔKE = (0.5)ΔEthermal

for substances in the solid and liquid states. Note that ΔEthermal is divided between ΔPE and ΔKE for substances in the solid and liquid states. This is because the intermolecular and intramolecular forces that exist between the atoms of the substance (i.e. atomic bond, van der Waals forces, etc) have not yet been dissociated and prevent the atomic particles from moving freely about the atmosphere (with velocity). Potential energy is just a way to have energy, and it generally describes the random movement that occurs when atoms are forced to be close to one another. Likewise, kinetic energy is just another way to have energy, which describes an atom's vigorous struggle to move and to break away from the group of atoms. The thermal energy that is added to the substance is thus divided equally between the potential and the kinetic energies because all aspects of the atoms' movement must be excited equally

However, once the intermolecular and intramolecular forces which restrict the atoms' movement are dissociated (when enough energy has been added), potential energy no longer exists (for monatomic gases) because the atoms of the substance are no longer forced to vibrate and be in contact with other atoms. When a group of atoms is in the gaseous state, it's atoms can devote all their energies into moving away from one another (kinetic energy).

Practical Applications of the Heat of Sublimation

The heat of sublimation can be useful in determining the effectiveness of medicines. Medicine is often administered in pill (solid) form, and the substances which they contain can sublime over time if the pill absorbs too much energy over time. Often times you may see the phrase "avoid excessive heat on the bottles of common painkillers (e.g. Advil). This is because in high temperature conditions, the pills can absorb heat energy, and sublimation can occur.

Practice Problems

- If the heat of fusion for H2O is 333.5 kJ/kg, the specific heat capacity of H2O(l) is 4.18 J/(g*K), the heat of vaporization for H2O is 2257 kJ/kg, then calculate the heat required to convert 1.00 kg of H2O(s) with the initial temperature of 273 K into steam at 373 K. Hint: 273 K is the solid-liquid phase change temperature and 373 K is the liquid-gas phase change temperature.

- Using the information given in question one, calculate the heat of sublimation for 1.00 mole H2O when the initial temperature of the solid is 273 K. Hint: molar mass of H2O is ~18.0 g/mol or 0.018 kg/mol.

- Using the information given in question one, calculate the heat of sublimation for 1.00 kg H2O when the initial temperature is 200 K. The specific heat capacity for H2O(s) is 2.05 kJ/(kg*K).

- If the heat of fusion for Au is 12.6 kJ/mol, the specific heat capacity of Au(l) is 25.4 J/(mol*K), the heat of vaporization for Au is 1701 kJ/kg, then calculate the heat of sublimation for 1.00 mol of Au(s) with the initial temperature, 1336 K. Hint: 1336 K is the solid-liquid phase change temperature, and 3243 K is the liquid-vapor phase change temperature.

- If the heat of sublimation for Cu is 349.9 kJ/mol, the specific heat capacity of Cu(l) is .0245 kJ/(mol*K), the heat of vaporization for Cu is 300.3 kJ/mol, then calculate the heat of fusion at 1357 K for 1.00 mol of Cu(s) with the temperature (Hint: 1357 K is the solid-liquid phase change temperature, and 2835 K is the liquid-vapor phase change temperature).

Solutions

- Break the evolution down into the constituent steps:

- Melting of 1 kg of H2O (ice) at \(T_i=273\; K\): \[(333.5\; kJ/\cancel{kg})(1.0\; \cancel{ kg})= 333.5\;kJ\]

- Heating up 1 kg of H2O (water) from \(T_i=273\;K\) to \(T_f=373\;K\): \[(1.0\; \cancel{ kg})(4.18\; \cancel{J}/\cancel{g} \cdot K)\left(\dfrac{1000\;\cancel{g}}{1 \; \cancel{kg}}\right) \left(\dfrac{1\;kJ}{1000 \; \cancel{J}}\right) (373 \;K - 273 \;K)=418\;kJ\]

- Boiling1 kg of H2O (water) into vapor: \[(2257 \;kJ/\cancel{kg})(1.0 \;\cancel{kg}) = 2257\; kJ\]

- Add them all together to get the total enthalpy added \[= 333.5\;kJ + 418\;kJ + 2257\; kJ = 3008.5\; kJ\]

- \(\Delta H_{sub}\) for 1 mol H2O (at Ti=273K)= (3008.5 kJ/kg)(0.018 kg/mol) = 54.153 kJ/mol

- \(\Delta H_{sub}\) for 1 kg H2O (at Ti=200K)= 3008.5 kJ/kg + (2.05 kJ/K*kg)(1.0kg)(273-200K) = 3158.15 kJ/kg

- \(\Delta H_{sub}\) for 1 mol Au (at Ti=1336K)= (12.6 kJ/mol)(1\;mol) + (.0254 kJ/mol*K)(3243-1336\;K) + (1701 kJ/kg)(0.197 kg/mol) = 396.1 kJ/mol

- \(\Delta H_{fus}\) for Cu (at T=1356K) = 349.9 kJ/mol - (0.0245 kJ/mol*K)(2843-1357\;K) - (300.3 kJ/mol)(1\;mol) = 13.2 kJ/mol

Footnotes

1.

Dmitry Bedrov, Oleg Borodin, Grant D. Smith, Thomas D. Sewell, Dana M. Dattelbaum, and Lewis L. Steven. "A molecular dynamics simulation study of crystalline 1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene as a function of pressure and temperature." THE JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL PHYSICS 131, 2009.2.

Advil bottle. 24 Ibuprofen tablets, 200mg. EXP 12/08.3.

Pascal Taulelle, Georges Sitja, Gerard Pepe, Eric Garcia, Christian Hoff, and Stephane Veesler. "Measuring Enthalpy of Sublimation for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: Validate Crystal Energy and Predict Crystal Habit." Crystal Growth & Design (2009): 4706–4709. Print.External References

- Advil bottle. 24 Ibuprofen tablets, 200mg. EXP 12/08.

- Dmitry Bedrov, Oleg Borodin, Grant D. Smith, Thomas D. Sewell, Dana M. Dattelbaum, and Lewis L. Steven. "A molecular dynamics simulation study of crystalline 1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene as a function of pressure and temperature." The Journal of Chemical Physics 131 (2009): 1-4.

- Pascal Taulelle, Georges Sitja, Gerard Pepe, Eric Garcia, Christian Hoff, and Stephane Veesler. "Measuring Enthalpy of Sublimation for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: Validate Crystal Energy and Predict Crystal Habit." Crystal Growth & Design (2009): 4706–4709.

- Petrucci, Ralph H., William S. Harwood, F. G. Herring, and Jeffry D. Madura. General Chemistry: Principles & Modern Applications. 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007. 242-248.

- Potter, Wendell. "Applying Models to Thermal Phenomena." College Physics: A Models Approach, Part 1. Hayden McNeil Publishing: Plymouth, MI, 2010. 7-20.

Contributors and Attributions

- Kasey Nakajima (UCD)