6.3: Characteristics of C-13 NMR Spectroscopy

- Page ID

- 432204

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Understand where different types of carbon appear on the spectrum

Simply, 13C NMR allows you to determine how many different carbons are in a molecule. It will also be seen that information on functional groups present in a molecule can be determined using 13C NMR. In a spectrum, each signal represents a resonance for a different carbon atom. The typical range for the resonance frequencies is 0 to 220 ppm from tetramethylsilane (TMS) reference. Like 1H NMR, the chemical shift of 13C nuclei is influenced by its chemical environment like the 1H nuclei.

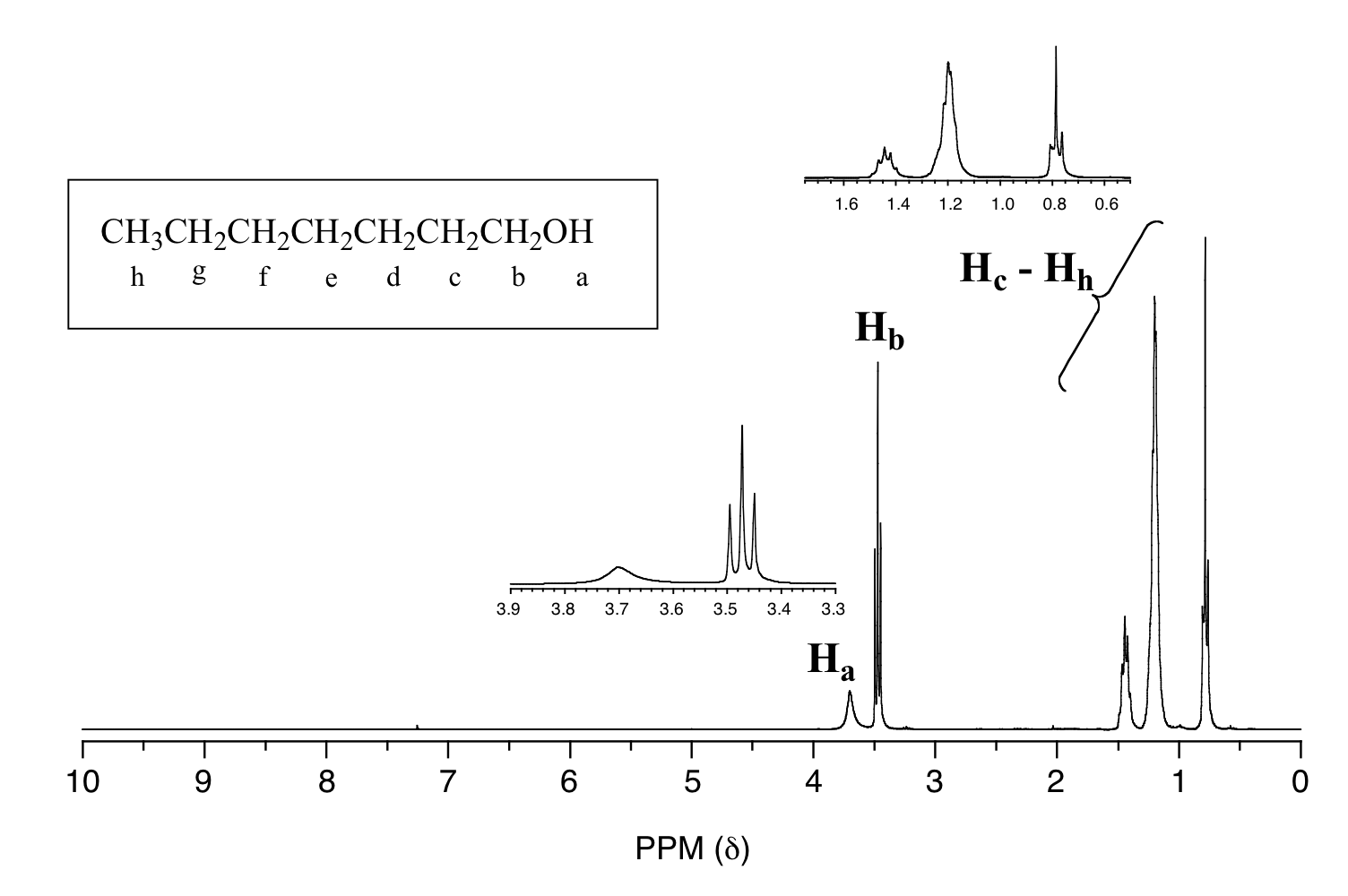

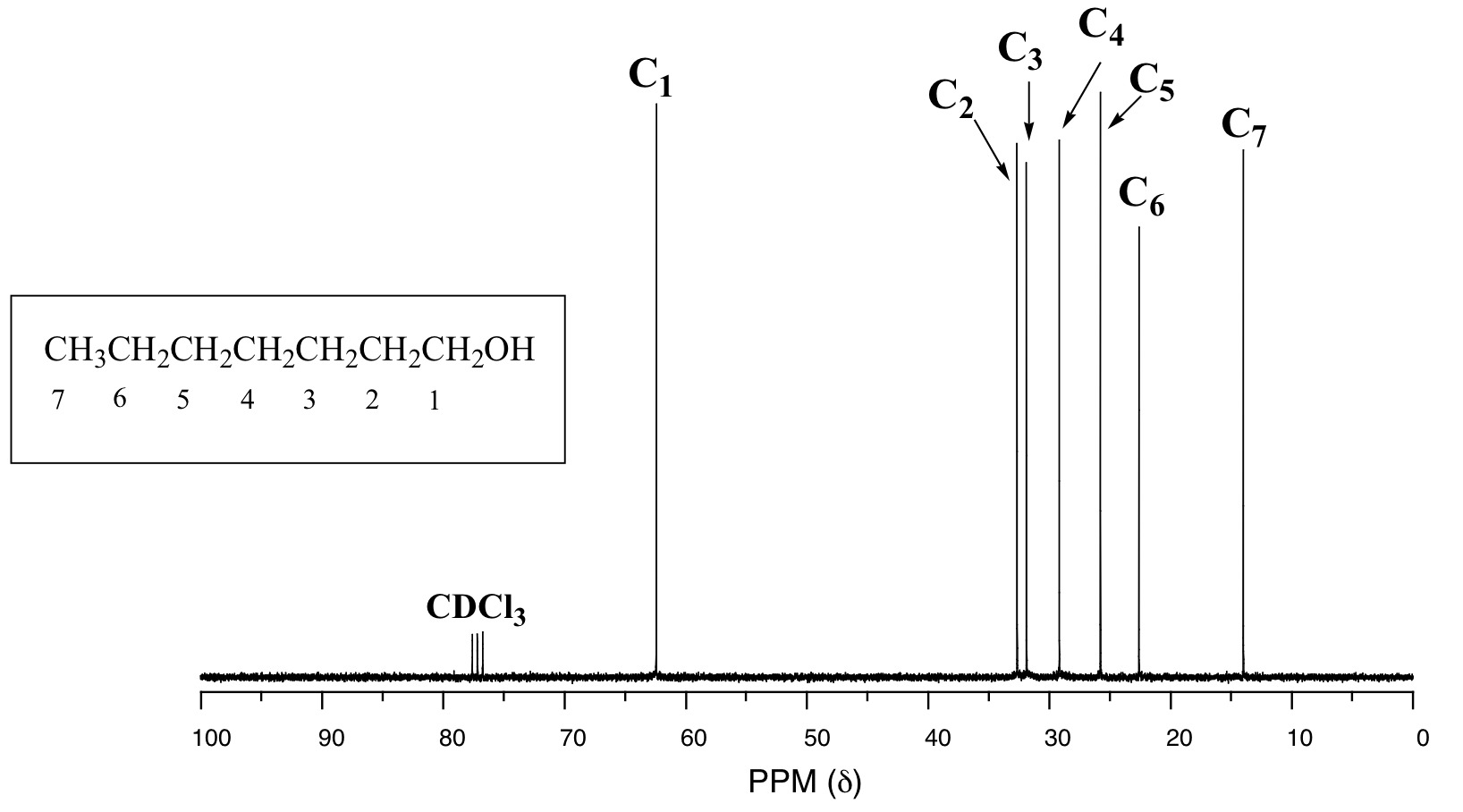

One of the greatest advantages of 13C-NMR compared to 1H-NMR is the breadth of the spectrum - carbons resonate from 0-220 ppm relative to the TMS standard, as opposed to only 0-12 ppm for protons. Because of this, 13C signals rarely overlap, meaning we can almost always distinguish separate peaks for each carbon, even in a relatively large compound containing carbons in very similar environments. In a 1H NMR spectrum of 1-heptanol, for example, many of the signals overlap and it becomes difficult to analyze, only the signals for the alcohol proton (Ha) and the two protons on the adjacent carbon (Hb) are easily analyzed.

In the 13C spectrum of 1-heptanol, we can easily distinguish each carbon signal, and we know from this data that our sample has seven non-equivalent carbons. (Notice also that, as we would expect, the chemical shifts of the carbons get progressively smaller as they get farther away from the deshielding oxygen.)

This property of 13C NMR makes it very helpful in the elucidation of larger, more complex structures.

Predict the number of carbon resonances expected in a 13C NMR spectrum of ethyl prop-2-enoate, C5H8O2.

Solution

There is no symmetry in this molecule, so you would expect 5 resonances - one for each C in the molecule - in a 13C NMR spectrum.

13C NMR spectrum of ethyl prop-2-en-oate:

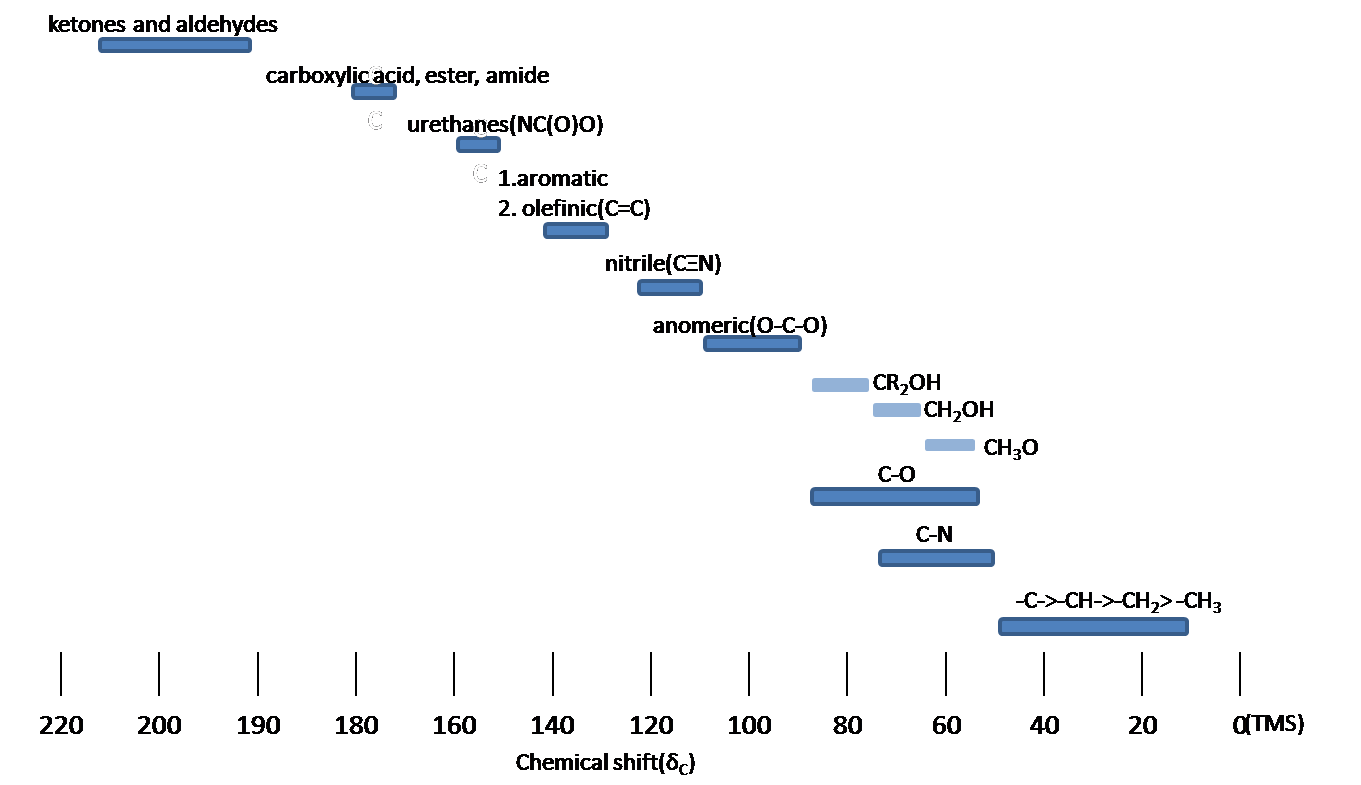

13C NMR Chemical Shifts

The 13C NMR is used for determining functional groups based on characteristic shift values. 13C chemical shifts are greatly affected by electronegative effects and magnetic anisotropy. If a H atom in an alkane is replaced by substituent X, electronegative atoms (O, N, halogen), 13C signals for nearby carbons shift downfield (left; increase in ppm) with the effect diminishing with distance from the electron withdrawing group just as in 1H NMR. Below, a typical 13C chemical shift table shows the regions of some of the common organic functional groups.

13C Chemical shift range for organic compounds

Assign the resonances in a 13C NMR spectrum of ethyl prop-2-enoate, C5H8O2.

Solution

There are 5 carbons in the molecule, which equate to the 5 peaks in the 13C NMR spectrum.

Using 13C NMR spectrum, how could you tell the difference between the isomers acetone and methoxy ethene?

vs.

- Answer

-

There are a few ways to tell the difference between the two molecules. Acetone would have 2 different resonances in a 13C NMR spectrum due to the symmetry of the molecule. Acetone is a ketone and ketone carbons appear far downfield 180-220 ppm. Methoxy ethene is difunctional molecule with an ether and an alkene. It would show 3 resonances in the 13C NMR spectrum, which all would be lower than the ketone resonance. Alkene resonances are 100-150 ppm and a C-O bond would be 40-85 ppm.

Assign as many peaks as you can to the 13C NMR spectrum to specific carbons in the N-ethylbenzamide.

13C NMR spectrum:

- Answer

-

While there are 9 total carbons, there are only 7 non-equivalent carbons.

Labeled Carbon Number Chemical Shift (ppm) 1 14.80 2 34.80 3 134.40 4 126.70 5 128.10 6 130.90 7 167.20

Contributors and Attributions

Prof. Steven Farmer (Sonoma State University)

Organic Chemistry With a Biological Emphasis by Tim Soderberg (University of Minnesota, Morris)

Chris P Schaller, Ph.D., (College of Saint Benedict / Saint John's University)