3.3: Electronic Transitions

- Page ID

- 432171

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Objectives

- discuss the bonding in 1,3-butadiene in terms of the molecular orbital theory, and draw a molecular orbital for this and similar compounds.

- understand how electronic transitions occur.

- get an understanding of when electronic transitions can be observed with UV spectroscopy

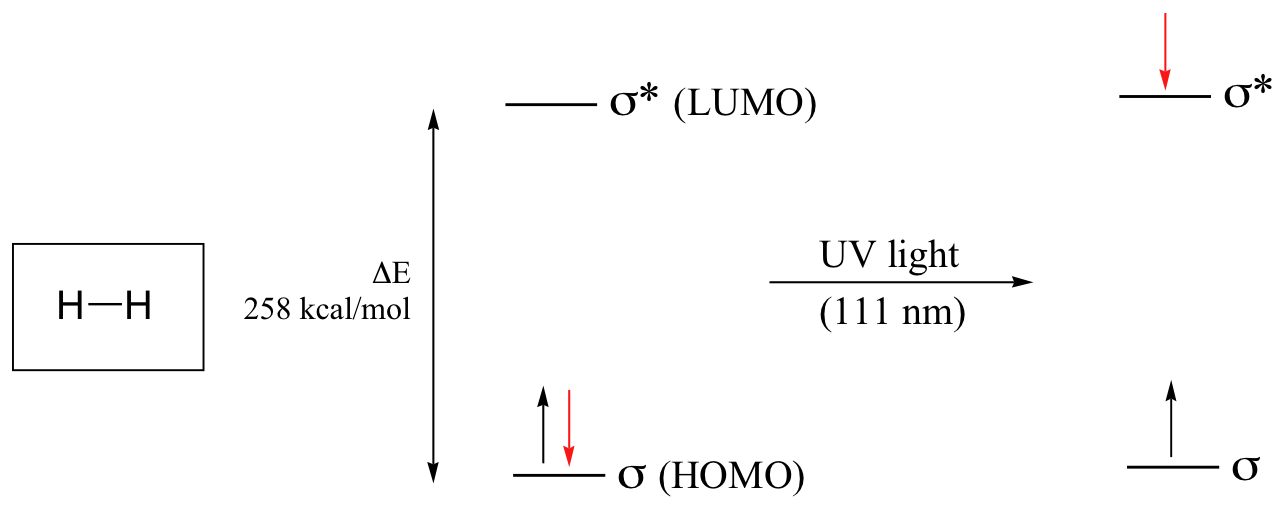

Let’s take as our first example the simple case of molecular hydrogen, H2. The molecular orbital picture for the hydrogen molecule consists of one bonding σ MO, and a higher energy antibonding σ* MO. When the molecule is in the ground state, both electrons are paired in the lower-energy bonding orbital – this is the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO). The antibonding σ* orbital, in turn, is the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO).

If the molecule is exposed to light of a wavelength with energy equal to ΔE, the HOMO-LUMO energy gap, this wavelength will be absorbed and the energy used to bump one of the electrons from the HOMO to the LUMO – in other words, from the σ to the σ* orbital. This is referred to as a σ - σ* transition. ΔE for this electronic transition is 258 kcal/mol, corresponding to light with a wavelength of 111 nm.

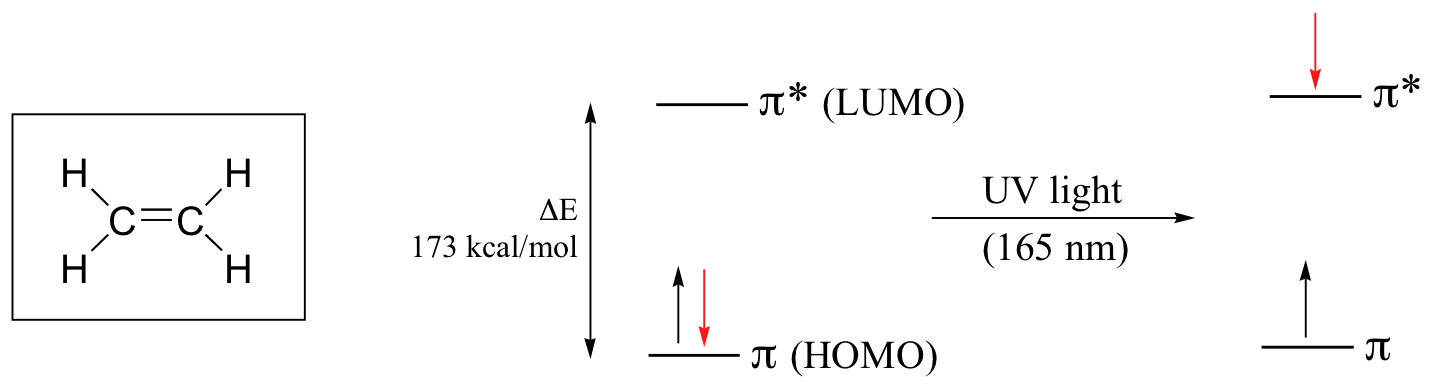

When a double-bonded molecule such as ethene (common name ethylene) absorbs light, it undergoes a π - π* transition. Because π- π* energy gaps are narrower than σ - σ* gaps, ethene absorbs light at 165 nm - a longer wavelength (lower energy) than molecular hydrogen.

The electronic transitions of both molecular hydrogen and ethene are too energetic to be accurately recorded by standard UV spectrophotometers, which generally have a range of 220 – 700 nm. Where UV-vis spectroscopy becomes useful to most organic and biological chemists is in the study of molecules with conjugated pi systems. In these groups, the energy gap for π -π* transitions is smaller than for isolated double bonds, and thus the wavelength absorbed is longer. Molecules or parts of molecules that absorb light strongly in the UV-vis region are called chromophores.

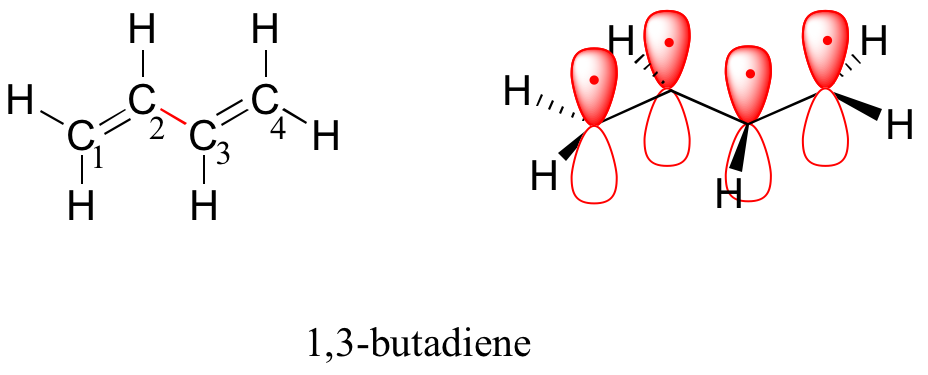

Next, we'll consider the 1,3-butadiene molecule (below). From valence orbital theory alone we might expect that the C2-C3 bond in this molecule, because it is a sigma bond, would be able to rotate freely.

Experimentally, however, it is observed that there is a significant barrier to rotation about the C2-C3 bond (colored in red above), and that the entire molecule is planar. In addition, the C2-C3 bond is 148 pm long, shorter than a typical carbon-carbon single bond (about 154 pm), though longer than a typical double bond (about 134 pm). Molecular orbital theory accounts for these observations with the concept of delocalized π bonds. In this picture, the four p atomic orbitals combine mathematically to form four pi molecular orbitals of increasing energy. Two of these - the bonding pi orbitals - are lower in energy than the p atomic orbitals from which they are formed, while two - the antibonding pi orbitals - are higher in energy.

The lowest energy molecular orbital, pi1, has only constructive interaction and zero nodes. Higher in energy, but still lower than the isolated p orbitals, the pi2 orbital has one node but two constructive interactions - thus it is still a bonding orbital overall. Looking at the two antibonding orbitals, pi3* has two nodes and one constructive interaction, while pi4* has three nodes and zero constructive interactions.

By the aufbau principle, the four electrons from the isolated 2pz atomic orbitals are placed in the bonding pi1 and pi2 MO’s. Because pi1 includes constructive interaction between C2 and C3, there is a degree, in the 1,3-butadiene molecule, of pi-bonding interaction between these two carbons, which accounts for its shorter length and the barrier to rotation. The valence bond picture of 1,3-butadiene shows the two pi bonds as being isolated from one another, with each pair of pi electrons ‘stuck’ in its own pi bond. However, molecular orbital theory predicts (accurately) that the four pi electrons are to some extent delocalized, or ‘spread out’, over the whole pi system.

1,3-butadiene is the simplest example of a system of conjugated pi bonds. Remember to be considered conjugated, two or more pi bonds must be separated by only one single bond – in other words, there cannot be an intervening sp3-hybridized carbon, because this would break up the overlapping system of parallel p orbitals. In the compound below, for example, the C1-C2 and C3-C4 double bonds are conjugated (highlighted in blue), while the C6-C7 double bond (highlighted in red) is isolated from the other two pi bonds by sp3-hybridized C5.

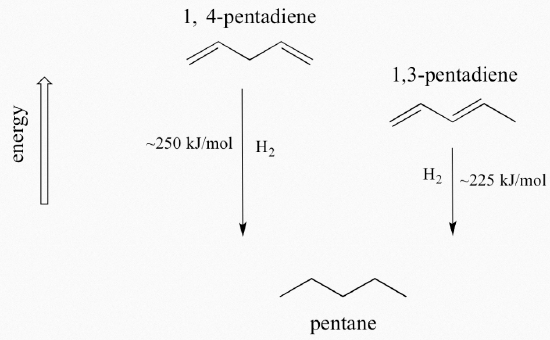

A very important concept to keep in mind is that there is an inherent thermodynamic stability associated with conjugation. This stability can be measured experimentally by comparing the heat of hydrogenation of two different dienes. When the two conjugated double bonds of 1,3-pentadiene are 'hydrogenated' to produce pentane, about 225 kJ is released per mole of pentane formed. Compare that to the approximately 250 kJ/mol released when the two isolated double bonds in 1,4-pentadiene are hydrogenated, also forming pentane.

The conjugated diene is lower in energy: in other words, it is more stable. In general, conjugated pi bonds are more stable than isolated pi bonds. Conjugated pi systems can involve heteroatoms like oxygen and nitrogen as well as carbon. In the metabolism of fat molecules, some of the key reactions involve alkenes that are conjugated to carbonyl groups.

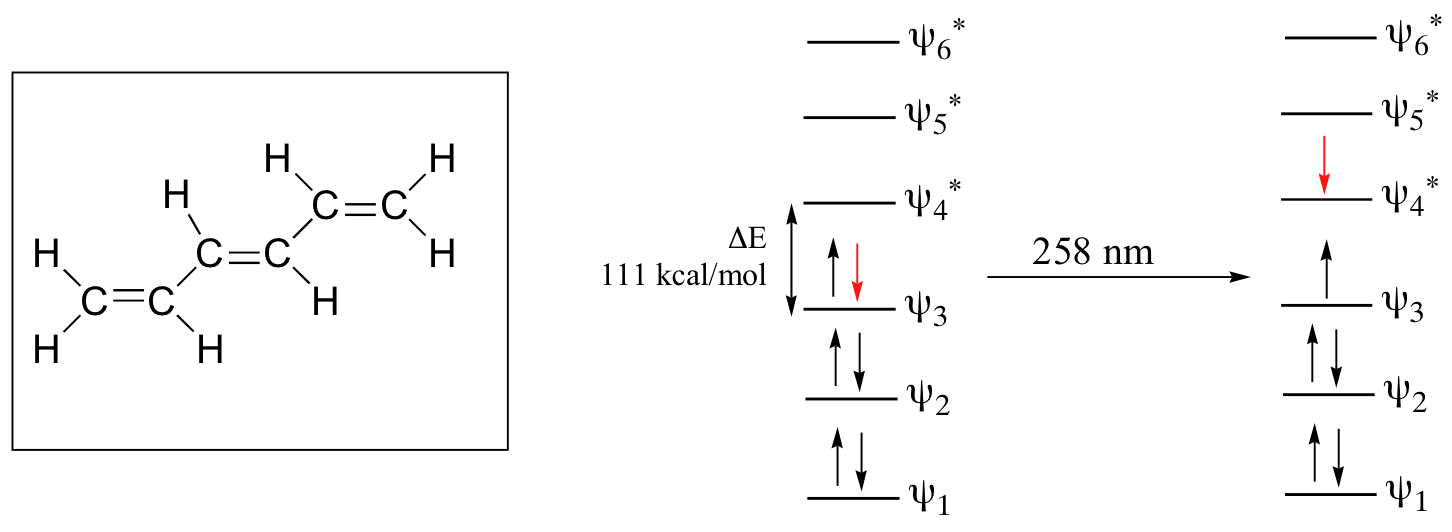

As conjugated pi systems become larger, the energy gap for a π - π* transition becomes increasingly narrow, and the wavelength of light absorbed correspondingly becomes longer. The absorbance due to the π - π* transition in 1,3,5-hexatriene, for example, occurs at 258 nm, corresponding to a ΔE of 111 kcal/mol.

In molecules with extended pi systems, the HOMO-LUMO energy gap becomes so small that absorption occurs in the visible rather then the UV region of the electromagnetic spectrum. Beta-carotene, with its system of 11 conjugated double bonds, absorbs light with wavelengths in the blue region of the visible spectrum while allowing other visible wavelengths – mainly those in the red-yellow region - to be transmitted. This is why carrots are orange.

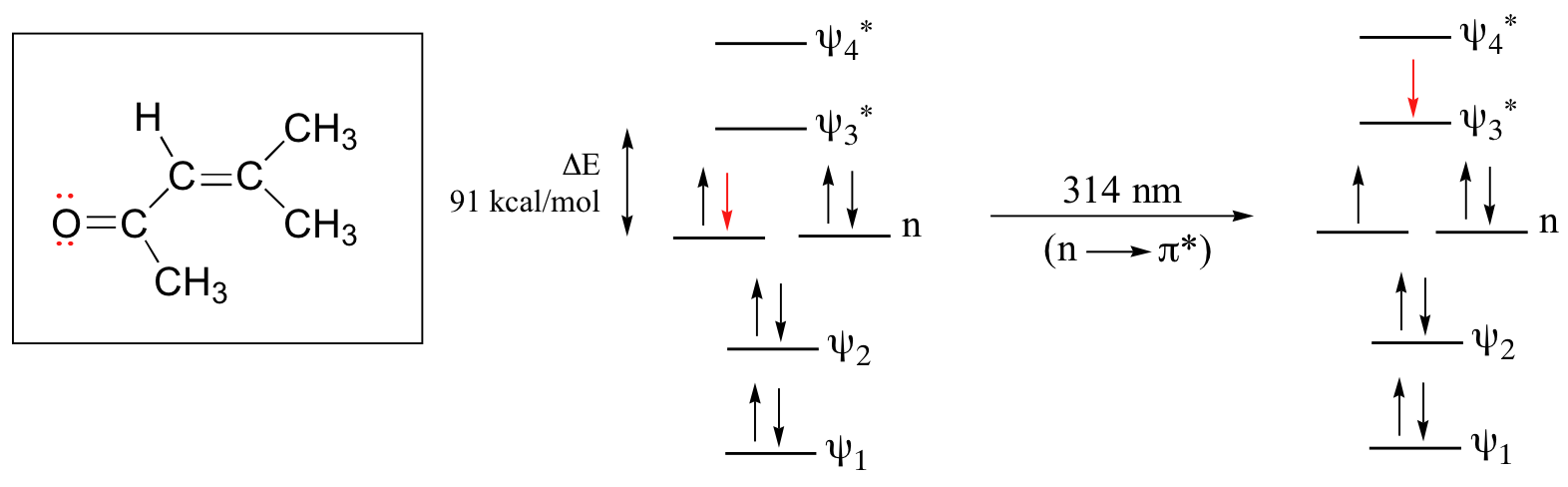

The conjugated pi system in 4-methyl-3-penten-2-one gives rise to a strong UV absorbance at 236 nm due to a π - π* transition. However, this molecule also absorbs at 314 nm. This second absorbance is due to the transition of a non-bonding (lone pair) electron on the oxygen up to a π* antibonding MO:

This is referred to as an n - π* transition. The nonbonding (n) MO’s are higher in energy than the highest bonding p orbitals, so the energy gap for an n - π* transition is smaller that that of a π - π* transition – and thus the n - π* peak is at a longer wavelength. In general, n - π* transitions are weaker (less light absorbed) than those due to π - π* transitions.

Without calculations, which molecule (2,5-heptadiene or 2,4-heptadiene) would you predict to have a lower heat of hydrogenation?

or

- Answer

-

I would predict 2,4-heptadiene to have a lower heat of hydrogenation than 2,5-heptadiene. This is due to the conjugation between the double bonds in 2,4-heptadiene, which is stabilizing.

Which of the following molecules would you expect to have a smaller gap in the electronic transition? Explain your answer.

- Answer

-

B. The entire molecule is conjugated, so it has a more extended pi system than A. More extended pi systems typically have smaller absorption gaps.

Contributors and Attributions

Dr. Dietmar Kennepohl FCIC (Professor of Chemistry, Athabasca University)

Prof. Steven Farmer (Sonoma State University)

William Reusch, Professor Emeritus (Michigan State U.), Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry

Organic Chemistry With a Biological Emphasis by Tim Soderberg (University of Minnesota, Morris)