8.2: Classification of Reagents as Electrophiles and Nucleophiles. Acids and Bases

- Page ID

- 22211

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

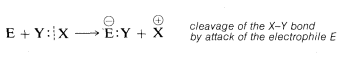

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)To understand ionic reactions, we need to be able to recognize whether a particular reagent will act to acquire an electron pair or to donate an electron pair. Reagents that acquire an electron pair in chemical reactions are said to be electrophilic ("electron-loving"). We can picture this in a general way as a heterolytic bond breaking of compound \(X:Y\) by an electrophile \(E\) such that \(E\) becomes bonded to \(Y\) by the electron pair of the \(XY\) bond. Thus

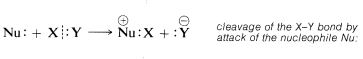

Reagents that donate an electron pair in chemical reactions are said to be nucleophilic ("nucleus loving"). Thus the \(X:Y\) bond also can be considered to be broken by the nucleophile \(Nu:\), which donates its electron pair to \(X\) while \(Y\) leaves as \(Y:^\ominus\) with the electrons of the \(X:Y\) bond:

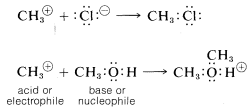

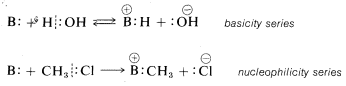

Thus, by definition, electrophiles are electron-pair acceptors and nucleophiles are electron-pair donors. These definitions correspond closely to definitions used in the generalized theory of acids and bases proposed by G. N. Lewis (1923). According to Lewis, an acid is any substance that can accept an electron pair, and a base is any substance that can donated an electron pair to form a covalent bond. Therefore acids must be electrophiles and bases must be nucleophiles. For example, the methyl cation may be regarded as a Lewis acid, or an electrophile, because it accepts electrons from reagents such as chloride ion or methanol. In turn, because chloride ion and methanol donate electrons to the methyl cation they are classified as Lewis bases, or nucleophiles:

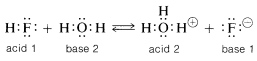

The generalized Lewis concept of acids and bases also includes common proton-transfer reactions.\(^1\) Thus water acts as a base because one of the electron pairs on oxygen can abstract a proton from a reagent such as hydrogen fluoride:

Alternatively, the hydronium ion (\(H_3O^\oplus\)) is an acid because it can accept electrons from another reagent (e.g., fluoride ion) by donating a proton.

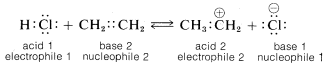

A proton donor can be classified as an electrophile and a proton acceptor as a nucleophile. For example, hydrogen chloride can transfer a proton to ethene to form the ethyl cation. Therefore hydrogen chloride functions as the electrophile, or acid, and ethene functions as the nucleophile, or base:

What then is the difference between an acid and an electrophile, or between a base and nucleophile? No great difference until we try to use the terms in a quantitative sense. For example, if we refer to acid strength, or acidity, this means the position of equilibrium in an acid-base reaction. The equilibrium constant \(K_a\) for the dissociation of an acid \(HA\), or the \(pK_a\), is a quantitative measure of acid strength. The larger the value of \(K_a\) or the smaller the \(pK_a\), the stronger the acid.

A summary of the relationships between \(K_a\) and \(pK_a\) follow, where the quantities in brackets are concentrations:

![Top: H A plus H 2 O is in equilibrium with H 3 O cation plus A minus. Bottom: K A equals [H 3 O cation] times [A anion] over [H A]. Text: Notice that the concentration of water does not appear in this expression; it is the solvent and its concentration is large and constant.](https://chem.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/68646/Roberts_and_Caserio_Screenshot_8-1-6.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=437&height=82)

or

![Negative log K A equals - log [H 3 O plus] plus log [H A] over [A anion].](https://chem.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/68647/Roberts_and_Caserio_Screenshot_8-1-7.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=223&height=59)

By definition, \(-\text{log} \: K_a = pK_a\) and \(-\text{log} \: \left[ H_3O^\oplus \right] = pH\); hence

![P K A equals P H plus log [H A] over [A anion].](https://chem.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/68648/Roberts_and_Caserio_Screenshot_8-1-8.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=144&height=59)

or

![P K A equals P H plus log [undissociated acid] over [anion of the acid]. Text: this sometimes is referred to as the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation.](https://chem.libretexts.org/@api/deki/files/68649/Roberts_and_Caserio_Screenshot_8-1-9.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=455&height=59)

However, in referring to the strength of reagents as electrophiles or nucleophiles we usually are not referring to chemical equilibria but to reaction rates. A good nucleophile is a reagent that reacts rapidly with a particular electrophile. In contrast, a poor nucleophile reacts only slowly with the same electrophile. Consequently, it should not then be taken for granted that there is a parallel between the acidity or basicity of a reagent and its reactivity as an electrophile or nucleophile. For instance, it is incorrect to assume that the strengths of a series of bases, \(B:\), in aqueous solution will necessarily parallel their nucleophilicities toward a carbon electrophile, such as methyl chloride:

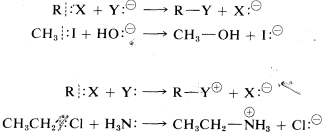

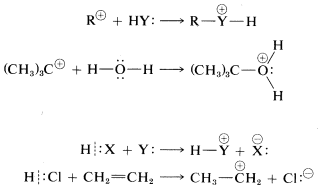

In what follows we will be concerned with the rates of ionic reactions under nonequilibrium conditions. We shall use the term nucleophilic repeatedly and we want you to understand that a nucleophile is any neutral or charged reagent that supplies a pair of electrons, either bonding or nonbonding, to form a new covalent bond. In substitution reactions the nucleophile usually is an anion, \(Y:^\ominus\), or a neutral molecule, \(Y:\) or \(HY:\). The operation of each of these is illustrated in the following equations for reactions of the general compound \(RX\) and some specific examples:

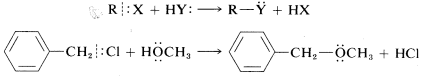

An electrophile is any neutral or charged reagent that accepts an electron pair (from a nucleophile) to form a new bond. In the preceding substitution reactions, the electrophile is \(RX\). The electrophile in other reactions may be a carbon cation or a proton donor, as in the following examples:

\(^1\)The concept of an acid as a proton donor and a base as a proton acceptor is due to Bronsted and Lowry (1923). Previous to this time, acids and bases generally were defined as substances that functioned by forming \(H^\oplus\) or \(OH^\ominus\) in water solutions. The Bronsted-Lowry concept was important because it liberated acid-base phenomena from the confines of water-containing solvents by focusing attention on proton transfers rather than the formation of \(H^\oplus\) or \(OH^\ominus\). The Lewis concept of generalized acids and bases further broadened the picture by showing the relationship between proton transfers and reactions where an electron-pair acceptor is transferred from one electron-pair donor to another.

Contributors and Attributions

John D. Robert and Marjorie C. Caserio (1977) Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry, second edition. W. A. Benjamin, Inc. , Menlo Park, CA. ISBN 0-8053-8329-8. This content is copyrighted under the following conditions, "You are granted permission for individual, educational, research and non-commercial reproduction, distribution, display and performance of this work in any format."