6.1: What is an Acid and a Base?

- Page ID

- 371798

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)General Properties of Acids and Bases

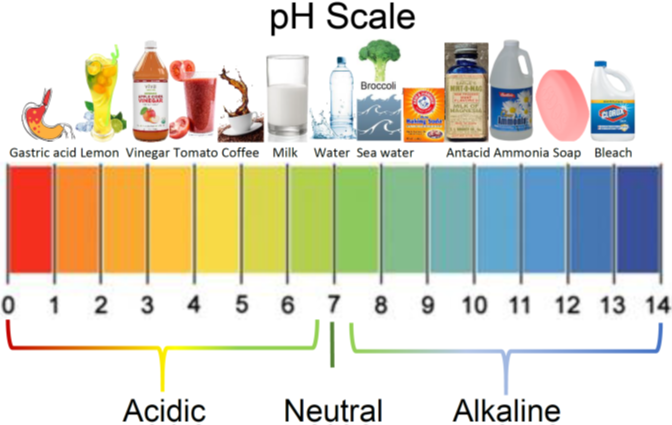

We commonly encounter acids and bases in our foods –some foods are acidic, and others are basic (alkaline) as illustrated in Fig. 6.1.1.

The general properties of acids and bases are the following.

- Acids taste sour, e.g., citrus fruits taste source because of citrus acid and ascorbic acid, i.e., vitamin C, in them. Basic (alkaline) substances, on the other hand, taste bitter.

- Basic (alkaline) substances feel soupy, while acidic substances may sting.

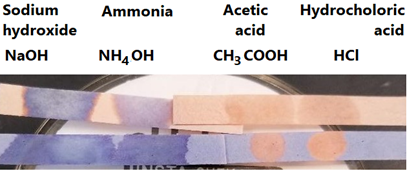

- The acids turn blue litmus paper to read but do not change the color of red litmus paper. Bases turn red litmus paper blue but do not change the color of blue litmus paper, as illustrated in Fig. 6.1.2.

- Phenolphthalein indicator turns colorless in acid and turns pink in basic solution, as illustrated in Fig. 6.1.3.

- Acids and bases neutralize each other. Hydrochloric acid is found in the stomach that helps digestion. Excess hydrochloric acid may cause acid burns—antacids like milk of magnesia are bases that help by neutralizing excess acid in the stomach.

Arrhenius's Definition of Acids and Bases

The earliest definition of acids and bases is Arrhenius's definition which states that:

- An acid is a substance that forms hydrogen ions H+ when dissolved in water, and

- A base is a substance that forms hydroxide ions OH- when dissolved in water.

For example, hydrochloric acid (\(\ce{HCl}\)) is an acid because it forms \(\ce{H^{+}}\) when it dissolves in water.

\[\mathrm{HCl}(\mathrm{g}) \stackrel{\text { Water }}{\longrightarrow} \mathrm{H}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{Cl}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})\nonumber\]

Similarly, NaOH is a base because it forms OH- when it dissolves in water.

\[\mathrm{NaOH}(\mathrm{s}) \stackrel{\text { Water }}{\longrightarrow} \mathrm{Na}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{OH}^{-}(\mathrm{aq})\nonumber\]

Note that hydrogen ion H+ does not exist in reality. It bonds with water molecules and exists as hydronium ion H3O+(aq).

\[\mathrm{H}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O} \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_{3} \mathrm{O}^{+}(\mathrm{aq})\nonumber\]

However, \(\ce{H^{+}(aq)}\) is often written in the place of (H3O+(aq).

Naming Arrhenius acids and bases

Table 1 lists the names and formulas of some of the common acids and their anions.

- The names end with the word “acid.”

- If the anion is not an oxyanion, then add the prefix hydro- to the name of the anion and change the last syllable of the anion name to –ic. For example, Cl- is a chloride ion, and HCl is hydrochloric acid.

- If the anion is an oxyanion with the last syllable –ate, change the last syllable with –ic. Do not use the prefix hydro-, but add the last word “acid.” If there is a prefix per- in the name of the oxyanion, retain the prefix in the acid name. For example, NO3- is a nitrate, and HNO3 is nitric acid. Another example, ClO4- is a perchlorate, and HClO3 is perchloric acid.

- If the anion is an oxyanion with the last syllable –ite, change the last syllable with –ous. Do not use the prefix hydro-, but add the last word “acid.” If there is a prefix hypo- in the name of the oxyanion, retain the prefix in the acid name. For example, NO2- is nitrite, and HNO2 is nitrous acid. Another example, ClO- is hypochlorite, and HClO is hypochlorous acid.

| Acid formula | Acid name | Anion | Anion name |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCl | Hydrochloric acid | Cl- | Chloride |

| HBr | Hydrobromic acid | Br- | Bromide |

| HI | Hydroiodic acid | I- | Iodide |

| HCN | Hydrocyanic acid | CN- | Cyanide |

| HNO3 | Nitric acid | NO3- | Nitrate |

| HNO2 | Nitrous acid | NO2- | Nitrite |

| H2SO4 | Sulfuric acid | SO42- | Sulfate |

| H2SO3 | Sulfurous acid | SO32- | Sulfite |

| H2CO3 | Carbonic acid | CO3- | Carbonate |

| CH3COOH | Acetic acid | CH3COO- | Acetate |

| H3PO4 | Phosphoric acid | PO43- | Phosphate |

| H3PO3 | Phosphorous acid | PO33- | Phosphite |

| HClO4 | Perchloric acid | ClO4- | Perchlorate |

| HClO3 | Chloric acid | ClO3- | Chlorate |

| HClO2 | Chlorous acid | ClO2- | Chlorite |

| HClO | Hypoclorous acid | ClO- | Hypochlorite |

Table 2 lists the names and formulas of some of the common Arrhenius bases.

The Arrhenius bases are ionic compounds of metal and hydroxide ion, and their name starts with the name of the metal element followed by the name of the anion, i.e., hydroxide. For example, NaOH is sodium hydroxide.

| Formula | Name |

|---|---|

| LiOH | Lithium hydroxide |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| KOH | Potassium hydroxide |

| Ca(OH)2 | Calcium hydroxide |

| Sr(OH)2 | Strontium hydroxide |

| Ba(OH)2 | Barium hydroxide |