21.6: The Kinetics of Radioactive Decay and Radiometric Dating

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 391515

Learning Objectives

- To know how to use half-lives to describe the rates of first-order reactions

Another approach to describing reaction rates is based on the time required for the concentration of a reactant to decrease to one-half its initial value. This period of time is called the half-life of the reaction, written as t1/2. Thus the half-life of a reaction is the time required for the reactant concentration to decrease from [A]0 to [A]0/2. If two reactions have the same order, the faster reaction will have a shorter half-life, and the slower reaction will have a longer half-life.

The half-life of a first-order reaction under a given set of reaction conditions is a constant. This is not true for zeroth- and second-order reactions. The half-life of a first-order reaction is independent of the concentration of the reactants. This becomes evident when we rearrange the integrated rate law for a first-order reaction to produce the following equation:

Substituting [A]0/2 for [A] and t1/2 for t (to indicate a half-life) into Equation \(\ref{21.4.1}\) gives

Substituting \(\ln{2} \approx 0.693\) into the equation results in the expression for the half-life of a first-order reaction:

\[t_{1/2}=\dfrac{0.693}{k} \label{21.4.2}\]

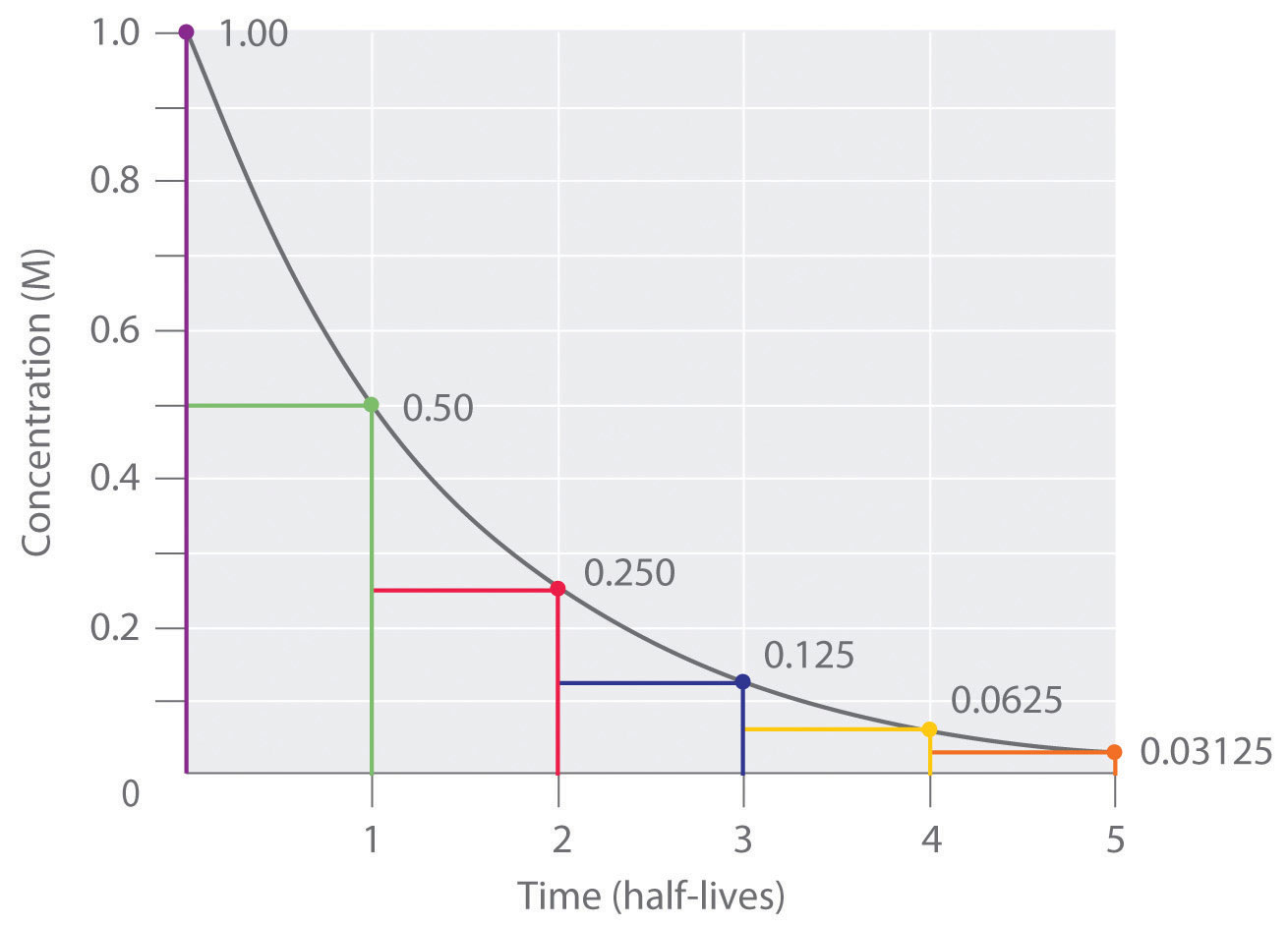

Thus, for a first-order reaction, each successive half-life is the same length of time, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), and is independent of [A].

If we know the rate constant for a first-order reaction, then we can use half-lives to predict how much time is needed for the reaction to reach a certain percent completion.

| Number of Half-Lives | Percentage of Reactant Remaining | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | \(\dfrac{100\%}{2}=50\%\) | \(\dfrac{1}{2}(100\%)=50\%\) |

| 2 | \(\dfrac{50\%}{2}=25\%\) | \(\dfrac{1}{2}\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)(100\%)=25\%\) |

| 3 | \(\dfrac{25\%}{2}=12.5\%\) | \(\dfrac{1}{2}\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right )\left (\dfrac{1}{2}\right)(100\%)=12.5\%\) |

| n | \(\dfrac{100\%}{2^n}\) | \(\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)^n(100\%)=\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)^n\%\) |

As you can see from this table, the amount of reactant left after n half-lives of a first-order reaction is (1/2)n times the initial concentration.

For a first-order reaction, the concentration of the reactant decreases by a constant with each half-life and is independent of [A].

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

The anticancer drug cis-platin hydrolyzes in water with a rate constant of 1.5 × 10−3 min−1 at pH 7.0 and 25°C. Calculate the half-life for the hydrolysis reaction under these conditions. If a freshly prepared solution of cis-platin has a concentration of 0.053 M, what will be the concentration of cis-platin after 5 half-lives? after 10 half-lives? What is the percent completion of the reaction after 5 half-lives? after 10 half-lives?

Given: rate constant, initial concentration, and number of half-lives

Asked for: half-life, final concentrations, and percent completion

Strategy:

- Use Equation \(\ref{21.4.2}\) to calculate the half-life of the reaction.

- Multiply the initial concentration by 1/2 to the power corresponding to the number of half-lives to obtain the remaining concentrations after those half-lives.

- Subtract the remaining concentration from the initial concentration. Then divide by the initial concentration, multiplying the fraction by 100 to obtain the percent completion.

Solution

A We can calculate the half-life of the reaction using Equation \(\ref{21.4.2}\):

\(t_{1/2}=\dfrac{0.693}{k}=\dfrac{0.693}{1.5\times10^{-3}\textrm{ min}^{-1}}=4.6\times10^2\textrm{ min}\)

Thus it takes almost 8 h for half of the cis-platin to hydrolyze.

B After 5 half-lives (about 38 h), the remaining concentration of cis-platin will be as follows:

After 10 half-lives (77 h), the remaining concentration of cis-platin will be as follows:

C The percent completion after 5 half-lives will be as follows:

The percent completion after 10 half-lives will be as follows:

Thus a first-order chemical reaction is 97% complete after 5 half-lives and 100% complete after 10 half-lives.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Ethyl chloride decomposes to ethylene and HCl in a first-order reaction that has a rate constant of 1.6 × 10−6 s−1 at 650°C.

- What is the half-life for the reaction under these conditions?

- If a flask that originally contains 0.077 M ethyl chloride is heated at 650°C, what is the concentration of ethyl chloride after 4 half-lives?

- Answer a

-

4.3 × 105 s = 120 h = 5.0 days;

- Answer b

-

4.8 × 10−3 M

Radioactive Decay Rates

Radioactivity, or radioactive decay, is the emission of a particle or a photon that results from the spontaneous decomposition of the unstable nucleus of an atom. The rate of radioactive decay is an intrinsic property of each radioactive isotope that is independent of the chemical and physical form of the radioactive isotope. The rate is also independent of temperature. In this section, we will describe radioactive decay rates and how half-lives can be used to monitor radioactive decay processes.

In any sample of a given radioactive substance, the number of atoms of the radioactive isotope must decrease with time as their nuclei decay to nuclei of a more stable isotope. Using N to represent the number of atoms of the radioactive isotope, we can define the rate of decay of the sample, which is also called its activity (A) as the decrease in the number of the radioisotope’s nuclei per unit time:

Activity is usually measured in disintegrations per second (dps) or disintegrations per minute (dpm).

The activity of a sample is directly proportional to the number of atoms of the radioactive isotope in the sample:

\[A = kN \label{21.4.4}\]

Here, the symbol k is the radioactive decay constant, which has units of inverse time (e.g., s−1, yr−1) and a characteristic value for each radioactive isotope. If we combine Equation \(\ref{21.4.3}\) and Equation \(\ref{21.4.4}\), we obtain the relationship between the number of decays per unit time and the number of atoms of the isotope in a sample:

Equation \(\ref{21.4.5}\) is the same as the equation for the reaction rate of a first-order reaction, except that it uses numbers of atoms instead of concentrations. In fact, radioactive decay is a first-order process and can be described in terms of either the differential rate law (Equation \(\ref{21.4.5}\)) or the integrated rate law:

\[N = N_0e^{−kt} \]

\[\ln \dfrac{N}{N_0}=-kt \label{21.4.6}\]

Because radioactive decay is a first-order process, the time required for half of the nuclei in any sample of a radioactive isotope to decay is a constant, called the half-life of the isotope. The half-life tells us how radioactive an isotope is (the number of decays per unit time); thus it is the most commonly cited property of any radioisotope. For a given number of atoms, isotopes with shorter half-lives decay more rapidly, undergoing a greater number of radioactive decays per unit time than do isotopes with longer half-lives. The half-lives of several isotopes are listed in Table 14.6, along with some of their applications.

| Radioactive Isotope | Half-Life | Typical Uses |

|---|---|---|

| *The m denotes metastable, where an excited state nucleus decays to the ground state of the same isotope. | ||

| hydrogen-3 (tritium) | 12.32 yr | biochemical tracer |

| carbon-11 | 20.33 min | positron emission tomography (biomedical imaging) |

| carbon-14 | 5.70 × 103 yr | dating of artifacts |

| sodium-24 | 14.951 h | cardiovascular system tracer |

| phosphorus-32 | 14.26 days | biochemical tracer |

| potassium-40 | 1.248 × 109 yr | dating of rocks |

| iron-59 | 44.495 days | red blood cell lifetime tracer |

| cobalt-60 | 5.2712 yr | radiation therapy for cancer |

| technetium-99m* | 6.006 h | biomedical imaging |

| iodine-131 | 8.0207 days | thyroid studies tracer |

| radium-226 | 1.600 × 103 yr | radiation therapy for cancer |

| uranium-238 | 4.468 × 109 yr | dating of rocks and Earth’s crust |

| americium-241 | 432.2 yr | smoke detectors |

Note

Radioactive decay is a first-order process.

Radioisotope Dating Techniques

In our earlier discussion, we used the half-life of a first-order reaction to calculate how long the reaction had been occurring. Because nuclear decay reactions follow first-order kinetics and have a rate constant that is independent of temperature and the chemical or physical environment, we can perform similar calculations using the half-lives of isotopes to estimate the ages of geological and archaeological artifacts. The techniques that have been developed for this application are known as radioisotope dating techniques.

The most common method for measuring the age of ancient objects is carbon-14 dating. The carbon-14 isotope, created continuously in the upper regions of Earth’s atmosphere, reacts with atmospheric oxygen or ozone to form 14CO2. As a result, the CO2 that plants use as a carbon source for synthesizing organic compounds always includes a certain proportion of 14CO2 molecules as well as nonradioactive 12CO2 and 13CO2. Any animal that eats a plant ingests a mixture of organic compounds that contains approximately the same proportions of carbon isotopes as those in the atmosphere. When the animal or plant dies, the carbon-14 nuclei in its tissues decay to nitrogen-14 nuclei by a radioactive process known as beta decay, which releases low-energy electrons (β particles) that can be detected and measured:

\[ \ce{^{14}C \rightarrow ^{14}N + \beta^{−}} \label{21.4.7}\]

The half-life for this reaction is 5700 ± 30 yr.

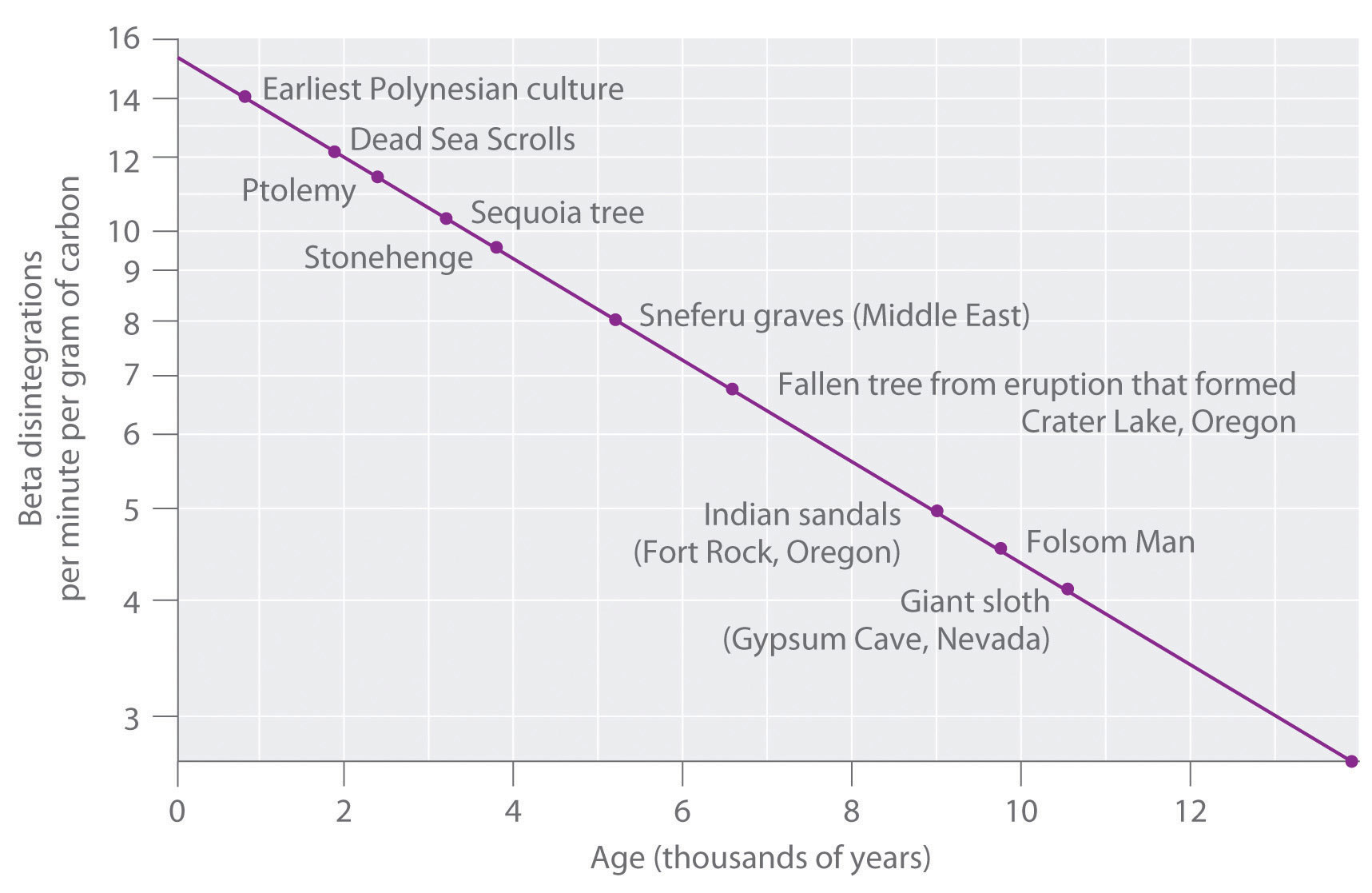

The 14C/12C ratio in living organisms is 1.3 × 10−12, with a decay rate of 15 dpm/g of carbon (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Comparing the disintegrations per minute per gram of carbon from an archaeological sample with those from a recently living sample enables scientists to estimate the age of the artifact, as illustrated in Example 11.Using this method implicitly assumes that the 14CO2/12CO2 ratio in the atmosphere is constant, which is not strictly correct. Other methods, such as tree-ring dating, have been used to calibrate the dates obtained by radiocarbon dating, and all radiocarbon dates reported are now corrected for minor changes in the 14CO2/12CO2 ratio over time.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

In 1990, the remains of an apparently prehistoric man were found in a melting glacier in the Italian Alps. Analysis of the 14C content of samples of wood from his tools gave a decay rate of 8.0 dpm/g carbon. How long ago did the man die?

Given: isotope and final activity

Asked for: elapsed time

Strategy:

A Use Equation \(\ref{21.4.4}\) to calculate N0/N. Then substitute the value for the half-life of 14C into Equation \(\ref{21.4.2}\) to find the rate constant for the reaction.

B Using the values obtained for N0/N and the rate constant, solve Equation \(\ref{21.4.6}\) to obtain the elapsed time.

Solution

We know the initial activity from the isotope’s identity (15 dpm/g), the final activity (8.0 dpm/g), and the half-life, so we can use the integrated rate law for a first-order nuclear reaction (Equation \(\ref{21.4.6}\)) to calculate the elapsed time (the amount of time elapsed since the wood for the tools was cut and began to decay).

\\ \dfrac{\ln(N/N_0)}{k}&=t\end{align}\)

A From Equation \(\ref{21.4.4}\), we know that A = kN. We can therefore use the initial and final activities (A0 = 15 dpm and A = 8.0 dpm) to calculate N0/N:

Now we need only calculate the rate constant for the reaction from its half-life (5730 yr) using Equation \(\ref{21.4.2}\):

This equation can be rearranged as follows:

B Substituting into the equation for t,

From our calculations, the man died 5200 yr ago.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

It is believed that humans first arrived in the Western Hemisphere during the last Ice Age, presumably by traveling over an exposed land bridge between Siberia and Alaska. Archaeologists have estimated that this occurred about 11,000 yr ago, but some argue that recent discoveries in several sites in North and South America suggest a much earlier arrival. Analysis of a sample of charcoal from a fire in one such site gave a 14C decay rate of 0.4 dpm/g of carbon. What is the approximate age of the sample?

- Answer

-

30,000 yr

Summary

- The half-life of a first-order reaction is independent of the concentration of the reactants.

- The half-lives of radioactive isotopes can be used to date objects.

The half-life of a reaction is the time required for the reactant concentration to decrease to one-half its initial value. The half-life of a first-order reaction is a constant that is related to the rate constant for the reaction: t1/2 = 0.693/k. Radioactive decay reactions are first-order reactions. The rate of decay, or activity, of a sample of a radioactive substance is the decrease in the number of radioactive nuclei per unit time.