15.3: Acid and Base Strength

- Page ID

- 41623

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Assess the relative strengths of acids and bases according to their ionization constants

- Rationalize trends in acid–base strength in relation to molecular structure

- Carry out equilibrium calculations for weak acid–base systems

We can rank the strengths of acids by the extent to which they ionize in aqueous solution. The reaction of an acid with water is given by the general expression:

\[\ce{HA}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{A-}(aq)\]

Water is the base that reacts with the acid \(\ce{HA}\), \(\ce{A^{−}}\) is the conjugate base of the acid \(\ce{HA}\), and the hydronium ion is the conjugate acid of water. A strong acid yields 100% (or very nearly so) of \(\ce{H3O+}\) and \(\ce{A^{−}}\) when the acid ionizes in water; Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) lists several strong acids. A weak acid gives small amounts of \(\ce{H3O+}\) and \(\ce{A^{−}}\).

| Six Strong Acids | Six Strong Bases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\ce{HClO4}\) | perchloric acid | \(\ce{LiOH}\) | lithium hydroxide |

| \(\ce{HCl}\) | hydrochloric acid | \(\ce{NaOH}\) | sodium hydroxide |

| \(\ce{HBr}\) | hydrobromic acid | \(\ce{KOH}\) | potassium hydroxide |

| \(\ce{HI}\) | hydroiodic acid | \(\ce{Ca(OH)2}\) | calcium hydroxide |

| \(\ce{HNO3}\) | nitric acid | \(\ce{Sr(OH)2}\) | strontium hydroxide |

| \(\ce{H2SO4}\) | sulfuric acid | \(\ce{Ba(OH)2}\) | barium hydroxide |

The relative strengths of acids may be determined by measuring their equilibrium constants in aqueous solutions. In solutions of the same concentration, stronger acids ionize to a greater extent, and so yield higher concentrations of hydronium ions than do weaker acids. The equilibrium constant for an acid is called the acid-ionization constant, Ka. For the reaction of an acid \(\ce{HA}\):

\[\ce{HA}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{A-}(aq)\]

we write the equation for the ionization constant as:

\[K_\ce{a}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][A- ]}{[HA]}}\]

where the concentrations are those at equilibrium. Although water is a reactant in the reaction, it is also the solvent. If the solution is assumed to be dilute, the activity of the water is approximated by the activity of pure water, which is defined as having a value of 1. The larger the \(K_a\) of an acid, the larger the concentration of \(\ce{H3O+}\) and \(\ce{A^{−}}\) relative to the concentration of the nonionized acid, \(\ce{HA}\). Thus a stronger acid has a larger ionization constant than does a weaker acid. The ionization constants increase as the strengths of the acids increase.

The following data on acid-ionization constants indicate the order of acid strength: \(\ce{CH3CO2H} < \ce{HNO2} < \ce{HSO4-}\)

\[ \begin{aligned} \ce{CH3CO2H}(aq) + \ce{H2O}(l) &⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{CH3CO2-}(aq) \quad &K_\ce{a}=1.8×10^{−5} \\[4pt] \ce{HNO2}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l) &⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{NO2-}(aq) &K_\ce{a}=4.6×10^{-4} \\[4pt] \ce{HSO4-}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(aq) &⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq) & K_\ce{a}=1.2×10^{−2} \end{aligned}\]

Another measure of the strength of an acid is its percent ionization. The percent ionization of a weak acid is the ratio of the concentration of the ionized acid to the initial acid concentration, times 100:

\[\% \:\ce{ionization}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+]_{eq}}{[HA]_0}}×100\% \label{PercentIon} \]

Because the ratio includes the initial concentration, the percent ionization for a solution of a given weak acid varies depending on the original concentration of the acid, and actually decreases with increasing acid concentration.

Calculate the percent ionization of a 0.125-M solution of nitrous acid (a weak acid), with a pH of 2.09.

Solution

The percent ionization for an acid is:

\[\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+]_{eq}}{[HNO2]_0}}×100 \nonumber\]

The chemical equation for the dissociation of the nitrous acid is:

\[\ce{HNO2}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{NO2-}(aq)+\ce{H3O+}(aq). \nonumber\]

Since \(10^{−pH} = \ce{[H3O+]}\), we find that \(10^{−2.09} = 8.1 \times 10^{−3}\, M\), so that percent ionization (Equation \ref{PercentIon}) is:

\[\dfrac{8.1×10^{−3}}{0.125}×100=6.5\% \nonumber \]

Remember, the logarithm 2.09 indicates a hydronium ion concentration with only two significant figures.

Calculate the percent ionization of a 0.10 M solution of acetic acid with a pH of 2.89.

- Answer

-

1.3% ionized

We can rank the strengths of bases by their tendency to form hydroxide ions in aqueous solution. The reaction of a Brønsted-Lowry base with water is given by:

\[\ce{B}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{HB+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq)\]

Water is the acid that reacts with the base, \(\ce{HB^{+}}\) is the conjugate acid of the base \(\ce{B}\), and the hydroxide ion is the conjugate base of water. A strong base yields 100% (or very nearly so) of OH− and HB+ when it reacts with water; Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) lists several strong bases. A weak base yields a small proportion of hydroxide ions. Soluble ionic hydroxides such as NaOH are considered strong bases because they dissociate completely when dissolved in water.

As we did with acids, we can measure the relative strengths of bases by measuring their base-ionization constant (Kb) in aqueous solutions. In solutions of the same concentration, stronger bases ionize to a greater extent, and so yield higher hydroxide ion concentrations than do weaker bases. A stronger base has a larger ionization constant than does a weaker base. For the reaction of a base, \(\ce{B}\):

\[\ce{B}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{HB+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq),\]

we write the equation for the ionization constant as:

\[K_\ce{b}=\ce{\dfrac{[HB+][OH- ]}{[B]}}\]

where the concentrations are those at equilibrium. Again, we do not include [H2O] in the equation because water is the solvent. The chemical reactions and ionization constants of the three bases shown are:

\[ \begin{aligned} \ce{NO2-}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l) &⇌\ce{HNO2}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq) \quad &K_\ce{b}=2.17×10^{−11} \\[4pt] \ce{CH3CO2-}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l) &⇌\ce{CH3CO2H}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq) &K_\ce{b}=5.6×10^{−10} \\[4pt] \ce{NH3}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l) &⇌\ce{NH4+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq) &K_\ce{b}=1.8×10^{−5} \end{aligned}\]

A table of ionization constants of weak bases appears in Table E2. As with acids, percent ionization can be measured for basic solutions, but will vary depending on the base ionization constant and the initial concentration of the solution.

Consider the ionization reactions for a conjugate acid-base pair, \(\ce{HA − A^{−}}\):

\[\ce{HA}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{A-}(aq)\]

with \(K_\ce{a}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][A- ]}{[HA]}}\).

\[\ce{A-}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{OH-}(aq)+\ce{HA}(aq)\]

with \(K_\ce{b}=\ce{\dfrac{[HA][OH]}{[A- ]}}\).

Adding these two chemical equations yields the equation for the autoionization for water:

\[\begin{align*} \cancel{\ce{HA}(aq)}+\ce{H2O}(l)+\cancel{\ce{A-}(aq)}+\ce{H2O}(l) &⇌ \ce{H3O+}(aq)+\cancel{\ce{A-}(aq)}+\ce{OH-}(aq)+\cancel{\ce{HA}(aq)} \\[4pt] \ce{2H2O}(l) &⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq) \end{align*}\]

As shown in the previous chapter on equilibrium, the \(K\) expression for a chemical equation derived from adding two or more other equations is the mathematical product of the other equations’ \(K\) expressions. Multiplying the mass-action expressions together and cancelling common terms, we see that:

\[K_\ce{a}×K_\ce{b}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][A- ]}{[HA]}×\dfrac{[HA][OH- ]}{[A- ]}}=\ce{[H3O+][OH- ]}=K_\ce{w}\]

For example, the acid ionization constant of acetic acid (CH3COOH) is 1.8 × 10−5, and the base ionization constant of its conjugate base, acetate ion (\(\ce{CH3COO-}\)), is 5.6 × 10−10. The product of these two constants is indeed equal to \(K_w\):

\[K_\ce{a}×K_\ce{b}=(1.8×10^{−5})×(5.6×10^{−10})=1.0×10^{−14}=K_\ce{w}\]

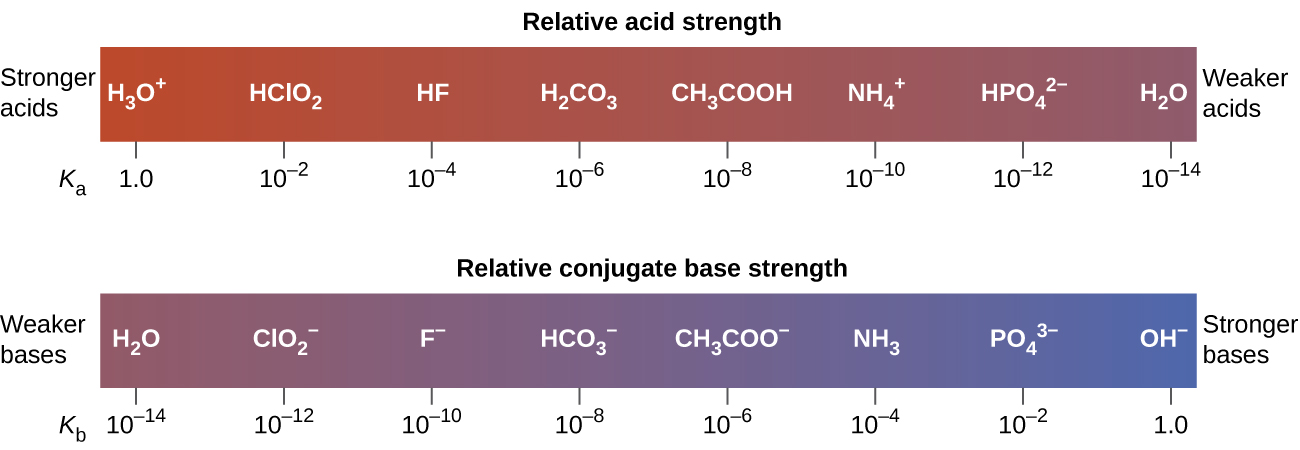

The extent to which an acid, \(\ce{HA}\), donates protons to water molecules depends on the strength of the conjugate base, \(\ce{A^{−}}\), of the acid. If \(\ce{A^{−}}\) is a strong base, any protons that are donated to water molecules are recaptured by \(\ce{A^{−}}\). Thus there is relatively little \(\ce{A^{−}}\) and \(\ce{H3O+}\) in solution, and the acid, \(\ce{HA}\), is weak. If \(\ce{A^{−}}\) is a weak base, water binds the protons more strongly, and the solution contains primarily \(\ce{A^{−}}\) and \(\ce{H3O^{+}}\)—the acid is strong. Strong acids form very weak conjugate bases, and weak acids form stronger conjugate bases (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

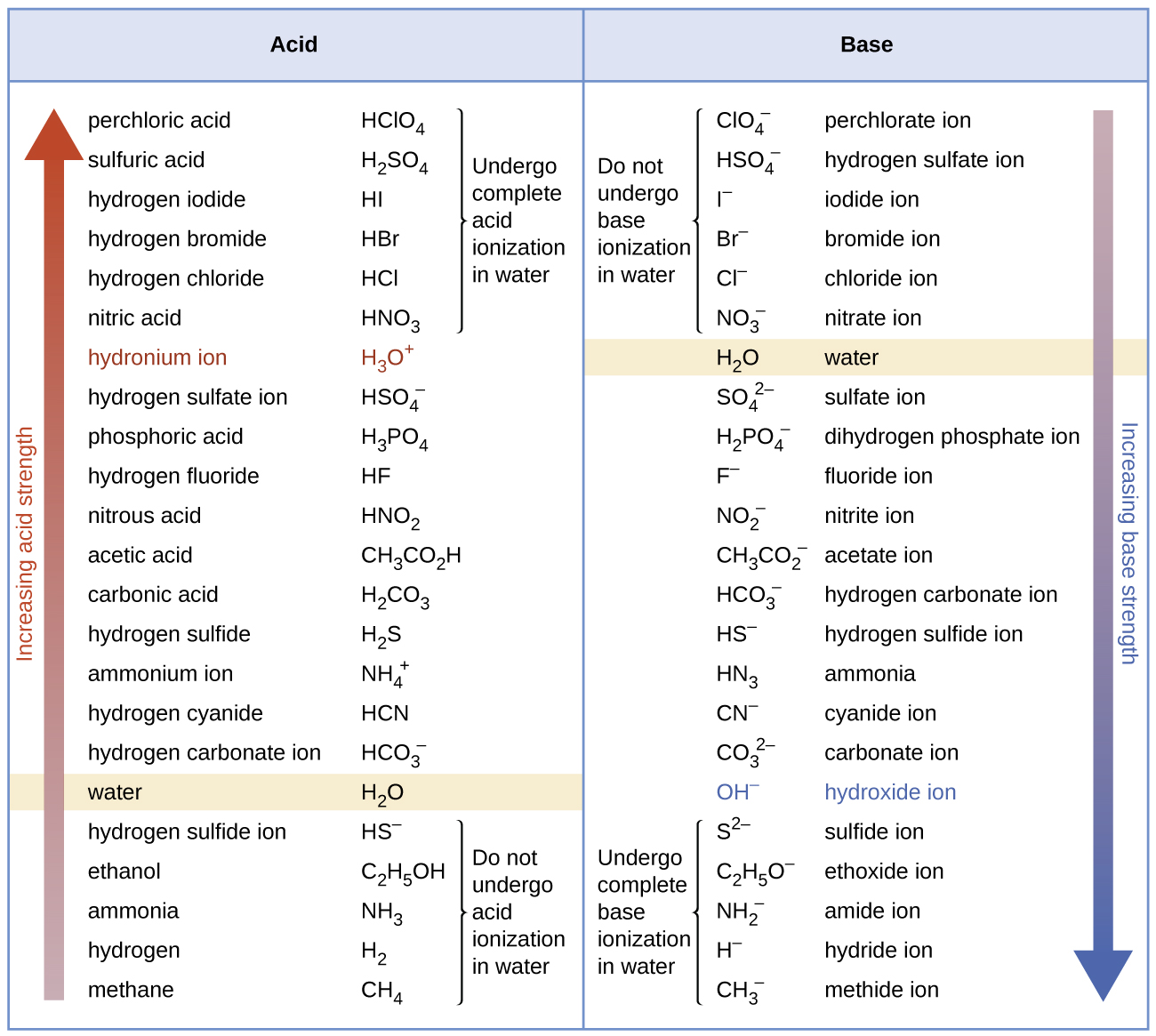

Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) lists a series of acids and bases in order of the decreasing strengths of the acids and the corresponding increasing strengths of the bases. The acid and base in a given row are conjugate to each other.

The first six acids in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) are the most common strong acids. These acids are completely dissociated in aqueous solution. The conjugate bases of these acids are weaker bases than water. When one of these acids dissolves in water, their protons are completely transferred to water, the stronger base.

Those acids that lie between the hydronium ion and water in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) form conjugate bases that can compete with water for possession of a proton. Both hydronium ions and nonionized acid molecules are present in equilibrium in a solution of one of these acids. Compounds that are weaker acids than water (those found below water in the column of acids) in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) exhibit no observable acidic behavior when dissolved in water. Their conjugate bases are stronger than the hydroxide ion, and if any conjugate base were formed, it would react with water to re-form the acid.

The extent to which a base forms hydroxide ion in aqueous solution depends on the strength of the base relative to that of the hydroxide ion, as shown in the last column in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). A strong base, such as one of those lying below hydroxide ion, accepts protons from water to yield 100% of the conjugate acid and hydroxide ion. Those bases lying between water and hydroxide ion accept protons from water, but a mixture of the hydroxide ion and the base results. Bases that are weaker than water (those that lie above water in the column of bases) show no observable basic behavior in aqueous solution.

Use the \(K_b\) for the nitrite ion, \(\ce{NO2-}\), to calculate the \(K_a\) for its conjugate acid.

Solution

Kb for \(\ce{NO2-}\) is given in this section as 2.17 × 10−11. The conjugate acid of \(\ce{NO2-}\) is HNO2; Ka for HNO2 can be calculated using the relationship:

\[K_\ce{a}×K_\ce{b}=1.0×10^{−14}=K_\ce{w} \nonumber \]

Solving for Ka, we get:

\[\begin{align*} K_\ce{a} &=\dfrac{K_\ce{w}}{K_\ce{b}} \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{1.0×10^{−14}}{2.17×10^{−11}} \\[4pt] &=4.6×10^{−4} \end{align*}\]

This answer can be verified by finding the Ka for HNO2 in Table E1

We can determine the relative acid strengths of \(\ce{NH4+}\) and \(\ce{HCN}\) by comparing their ionization constants. The ionization constant of \(\ce{HCN}\) is given in Table E1 as 4.9 × 10−10. The ionization constant of \(\ce{NH4+}\) is not listed, but the ionization constant of its conjugate base, \(\ce{NH3}\), is listed as 1.8 × 10−5. Determine the ionization constant of \(\ce{NH4+}\), and decide which is the stronger acid, \(\ce{HCN}\) or \(\ce{NH4+}\).

- Answer

-

\(\ce{NH4+}\) is the slightly stronger acid (Ka for \(\ce{NH4+}\) = 5.6 × 10−10).

Summary

The strengths of Brønsted-Lowry acids and bases in aqueous solutions can be determined by their acid or base ionization constants. Stronger acids form weaker conjugate bases, and weaker acids form stronger conjugate bases. Thus strong acids are completely ionized in aqueous solution because their conjugate bases are weaker bases than water. Weak acids are only partially ionized because their conjugate bases are strong enough to compete successfully with water for possession of protons. Strong bases react with water to quantitatively form hydroxide ions. Weak bases give only small amounts of hydroxide ion.

Key Equations

- \(K_\ce{a}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][A- ]}{[HA]}}\)

- \(K_\ce{b}=\ce{\dfrac{[HB+][OH- ]}{[B]}}\)

- \(K_a \times K_b = 1.0 \times 10^{−14} = K_w \,(\text{at room temperature})\)

Glossary

- acid ionization constant (Ka)

- equilibrium constant for the ionization of a weak acid

- base ionization constant (Kb)

- equilibrium constant for the ionization of a weak base

- leveling effect of water

- any acid stronger than \(\ce{H3O+}\), or any base stronger than OH− will react with water to form \(\ce{H3O+}\), or OH−, respectively; water acts as a base to make all strong acids appear equally strong, and it acts as an acid to make all strong bases appear equally strong

- percent ionization

- ratio of the concentration of the ionized acid to the initial acid concentration, times 100

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).