14.6: Reaction Mechanisms

- Page ID

- 46998

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- To determine the individual steps of a simple reaction.

One of the major reasons for studying chemical kinetics is to use measurements of the macroscopic properties of a system, such as the rate of change in the concentration of reactants or products with time, to discover the sequence of events that occur at the molecular level during a reaction. This molecular description is the mechanism of the reaction; it describes how individual atoms, ions, or molecules interact to form particular products. The stepwise changes are collectively called the reaction mechanism.

In an internal combustion engine, for example, isooctane reacts with oxygen to give carbon dioxide and water:

\[\ce{2C8H18 (l) + 25O2(g) -> 16CO2 (g) + 18H2O(g)} \label{14.6.1} \]

For this reaction to occur in a single step, 25 dioxygen molecules and 2 isooctane molecules would have to collide simultaneously and be converted to 34 molecules of product, which is very unlikely. It is more likely that a complex series of reactions takes place in a stepwise fashion. Each individual reaction, which is called an elementary reaction, involves one, two, or (rarely) three atoms, molecules, or ions. The overall sequence of elementary reactions is the mechanism of the reaction. The sum of the individual steps, or elementary reactions, in the mechanism must give the balanced chemical equation for the overall reaction.

The overall sequence of elementary reactions is the mechanism of the reaction.

Molecularity and the Rate-Determining Step

To demonstrate how the analysis of elementary reactions helps us determine the overall reaction mechanism, we will examine the much simpler reaction of carbon monoxide with nitrogen dioxide.

\[\ce{NO2(g) + CO(g) -> NO(g) + CO2 (g)} \label{14.6.2} \]

From the balanced chemical equation, one might expect the reaction to occur via a collision of one molecule of \(\ce{NO2}\) with a molecule of \(\ce{CO}\) that results in the transfer of an oxygen atom from nitrogen to carbon. The experimentally determined rate law for the reaction, however, is as follows:

\[rate = k[\ce{NO2}]^2 \label{14.6.3} \]

The fact that the reaction is second order in \([\ce{NO2}]\) and independent of \([\ce{CO}]\) tells us that it does not occur by the simple collision model outlined previously. If it did, its predicted rate law would be

\[rate = k[\ce{NO2}][\ce{CO}]. \nonumber \]

The following two-step mechanism is consistent with the rate law if step 1 is much slower than step 2:

| \(\textrm{step 1}\) | \(\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{NO_2}\xrightarrow{\textrm{slow}}\mathrm{NO_3}+\textrm{NO}\) | \(\textrm{elementary reaction}\) |

| \(\textrm{step 2}\) | \(\underline{\mathrm{NO_3}+\mathrm{CO}\rightarrow\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{CO_2}}\) | \(\textrm{elementary reaction}\) |

| \(\textrm{sum}\) | \(\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{CO}\rightarrow\mathrm{NO}+\mathrm{CO_2}\) | \(\textrm{overall reaction}\) |

According to this mechanism, the overall reaction occurs in two steps, or elementary reactions. Summing steps 1 and 2 and canceling on both sides of the equation gives the overall balanced chemical equation for the reaction. The \(\ce{NO3}\) molecule is an intermediate in the reaction, a species that does not appear in the balanced chemical equation for the overall reaction. It is formed as a product of the first step but is consumed in the second step.

The sum of the elementary reactions in a reaction mechanism must give the overall balanced chemical equation of the reaction.

Using Molecularity to Describe a Rate Law

The molecularity of an elementary reaction is the number of molecules that collide during that step in the mechanism. If there is only a single reactant molecule in an elementary reaction, that step is designated as unimolecular; if there are two reactant molecules, it is bimolecular; and if there are three reactant molecules (a relatively rare situation), it is termolecular. Elementary reactions that involve the simultaneous collision of more than three molecules are highly improbable and have never been observed experimentally. (To understand why, try to make three or more marbles or pool balls collide with one another simultaneously!)

Writing the rate law for an elementary reaction is straightforward because we know how many molecules must collide simultaneously for the elementary reaction to occur; hence the order of the elementary reaction is the same as its molecularity (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)). In contrast, the rate law for the reaction cannot be determined from the balanced chemical equation for the overall reaction. The general rate law for a unimolecular elementary reaction (A → products) is

\[rate = k[A]. \nonumber \]

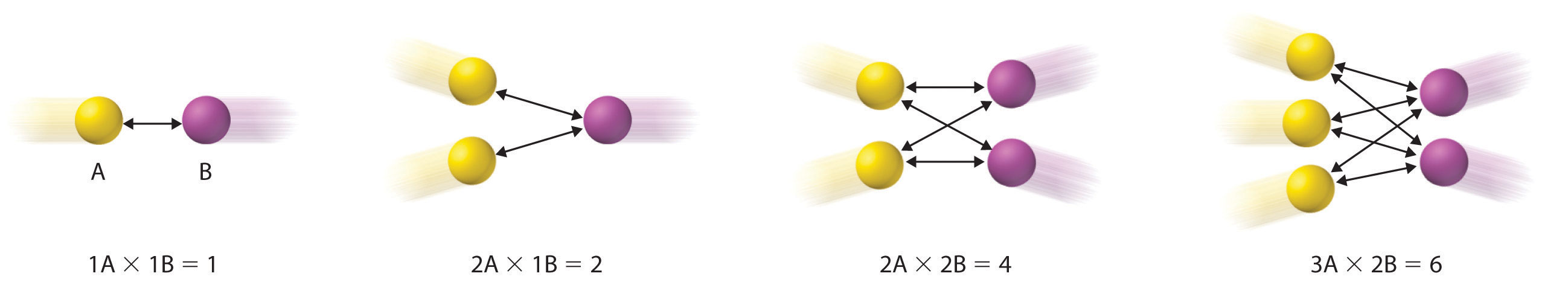

For bimolecular reactions, the reaction rate depends on the number of collisions per unit time, which is proportional to the product of the concentrations of the reactants, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). For a bimolecular elementary reaction of the form A + B → products, the general rate law is

\[rate = k[A][B]. \nonumber \]

| Elementary Reaction | Molecularity | Rate Law | Reaction Order |

|---|---|---|---|

| A → products | unimolecular | rate = k[A] | first |

| 2A → products | bimolecular | rate = k[A]2 | second |

| A + B → products | bimolecular | rate = k[A][B] | second |

| 2A + B → products | termolecular | rate = k[A]2[B] | third |

| A + B + C → products | termolecular | rate = k[A][B][C] | third |

For elementary reactions, the order of the elementary reaction is the same as its molecularity. In contrast, the rate law cannot be determined from the balanced chemical equation for the overall reaction (unless it is a single step mechanism and is therefore also an elementary step).

Identifying the Rate-Determining Step

Note the important difference between writing rate laws for elementary reactions and the balanced chemical equation of the overall reaction. Because the balanced chemical equation does not necessarily reveal the individual elementary reactions by which the reaction occurs, we cannot obtain the rate law for a reaction from the overall balanced chemical equation alone. In fact, it is the rate law for the slowest overall reaction, which is the same as the rate law for the slowest step in the reaction mechanism, the rate-determining step, that must give the experimentally determined rate law for the overall reaction.This statement is true if one step is substantially slower than all the others, typically by a factor of 10 or more. If two or more slow steps have comparable rates, the experimentally determined rate laws can become complex. Our discussion is limited to reactions in which one step can be identified as being substantially slower than any other. The reason for this is that any process that occurs through a sequence of steps can take place no faster than the slowest step in the sequence. In an automotive assembly line, for example, a component cannot be used faster than it is produced. Similarly, blood pressure is regulated by the flow of blood through the smallest passages, the capillaries. Because movement through capillaries constitutes the rate-determining step in blood flow, blood pressure can be regulated by medications that cause the capillaries to contract or dilate. A chemical reaction that occurs via a series of elementary reactions can take place no faster than the slowest step in the series of reactions.

Look at the rate laws for each elementary reaction in our example as well as for the overall reaction.

| \(\textrm{step 1}\) | \(\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{NO_2}\xrightarrow{\mathrm{k_1}}\mathrm{NO_3}+\textrm{NO}\) | \(\textrm{rate}=k_1[\mathrm{NO_2}]^2\textrm{ (predicted)}\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(\textrm{step 2}\) | \(\underline{\mathrm{NO_3}+\mathrm{CO}\xrightarrow{k_2}\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{CO_2}}\) | \(\textrm{rate}=k_2[\mathrm{NO_3}][\mathrm{CO}]\textrm{ (predicted)}\) |

| \(\textrm{sum}\) | \(\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{CO}\xrightarrow{k}\mathrm{NO}+\mathrm{CO_2}\) | \(\textrm{rate}=k[\mathrm{NO_2}]^2\textrm{ (observed)}\) |

The experimentally determined rate law for the reaction of \(NO_2\) with \(CO\) is the same as the predicted rate law for step 1. This tells us that the first elementary reaction is the rate-determining step, so \(k\) for the overall reaction must equal \(k_1\). That is, NO3 is formed slowly in step 1, but once it is formed, it reacts very rapidly with CO in step 2.

Sometimes chemists are able to propose two or more mechanisms that are consistent with the available data. If a proposed mechanism predicts the wrong experimental rate law, however, the mechanism must be incorrect.

In an alternative mechanism for the reaction of \(\ce{NO2}\) with \(\ce{CO}\) with \(\ce{N2O4}\) appearing as an intermediate.

| \(\textrm{step 1}\) | \(\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{NO_2}\xrightarrow{k_1}\mathrm{N_2O_4}\) |

|---|---|

| \(\textrm{step 2}\) | \(\underline{\mathrm{N_2O_4}+\mathrm{CO}\xrightarrow{k_2}\mathrm{NO}+\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{CO_2}}\) |

| \(\textrm{sum}\) | \(\mathrm{NO_2}+\mathrm{CO}\rightarrow\mathrm{NO}+\mathrm{CO_2}\) |

Write the rate law for each elementary reaction. Is this mechanism consistent with the experimentally determined rate law (rate = k[NO2]2)?

Given: elementary reactions

Asked for: rate law for each elementary reaction and overall rate law

Strategy:

- Determine the rate law for each elementary reaction in the reaction.

- Determine which rate law corresponds to the experimentally determined rate law for the reaction. This rate law is the one for the rate-determining step.

Solution

A The rate law for step 1 is rate = k1[NO2]2; for step 2, it is rate = k2[N2O4][CO].

B If step 1 is slow (and therefore the rate-determining step), then the overall rate law for the reaction will be the same: rate = k1[NO2]2. This is the same as the experimentally determined rate law. Hence this mechanism, with N2O4 as an intermediate, and the one described previously, with NO3 as an intermediate, are kinetically indistinguishable. In this case, further experiments are needed to distinguish between them. For example, the researcher could try to detect the proposed intermediates, NO3 and N2O4, directly.

Iodine monochloride (\(\ce{ICl}\)) reacts with \(\ce{H2}\) as follows:

\[\ce{2ICl(l) + H_2(g) \rightarrow 2HCl(g) + I_2(s)} \nonumber \]

The experimentally determined rate law is \(rate = k[\ce{ICl}][\ce{H2}]\). Write a two-step mechanism for this reaction using only bimolecular elementary reactions and show that it is consistent with the experimental rate law. (Hint: \(\ce{HI}\) is an intermediate.)

Answer

| \(\textrm{step 1}\) | \(\mathrm{ICl}+\mathrm{H_2}\xrightarrow{k_1}\mathrm{HCl}+\mathrm{HI}\) | \(\mathrm{rate}=k_1[\mathrm{ICl}][\mathrm{H_2}]\,(\textrm{slow})\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(\textrm{step 2}\) | \(\underline{\mathrm{HI}+\mathrm{ICl}\xrightarrow{k_2}\mathrm{HCl}+\mathrm{I_2}}\) | \(\mathrm{rate}=k_2[\mathrm{HI}][\mathrm{ICl}]\,(\textrm{fast})\) |

| \(\textrm{sum}\) | \(\mathrm{2ICl}+\mathrm{H_2}\rightarrow\mathrm{2HCl}+\mathrm{I_2}\) |

This mechanism is consistent with the experimental rate law if the first step is the rate-determining step.

Assume the reaction between \(\ce{NO}\) and \(\ce{H_2}\) occurs via a three-step process:

| \(\textrm{step 1}\) | \(\mathrm{NO}+\mathrm{NO}\xrightarrow{k_1}\mathrm{N_2O_2}\) | \(\textrm{(fast)}\) |

|---|---|---|

| \(\textrm{step 2}\) | \(\mathrm{N_2O_2}+\mathrm{H_2}\xrightarrow{k_2}\mathrm{N_2O}+\mathrm{H_2O}\) | \(\textrm{(slow)}\) |

| \(\textrm{step 3}\) | \(\mathrm{N_2O}+\mathrm{H_2}\xrightarrow{k_3}\mathrm{N_2}+\mathrm{H_2O}\) | \(\textrm{(fast)}\) |

Write the rate law for each elementary reaction, write the balanced chemical equation for the overall reaction, and identify the rate-determining step. Is the rate law for the rate-determining step consistent with the experimentally derived rate law for the overall reaction:

\[\text{rate} = k[\ce{NO}]^2[\ce{H_2}]? \tag{observed} \]

Answer

- Step 1: \(rate = k_1[\ce{NO}]^2\)

- Step 2: \(rate = k_2[\ce{N_2O_2}][\ce{H_2}]\)

- Step 3: \(rate = k_3[\ce{N_2O}][\ce{H_2}]\)

The overall reaction is then

\[\ce{2NO(g) + 2H_2(g) -> N2(g) + 2H2O(g)} \nonumber \]

- Rate Determining Step : #2

- Yes, because the rate of formation of \([\ce{N_2O_2}] = k_1[\ce{NO}]^2\). Substituting \(k_1[\ce{NO}]^2\) for \([\ce{N_2O_2}]\) in the rate law for step 2 gives the experimentally derived rate law for the overall chemical reaction, where \(k = k_1k_2\).

Reaction Mechanism (Slow step followed by fast step): Reaction Mechanism (Slow step Followed by Fast Step)(opens in new window) [youtu.be] (opens in new window)

Summary

A balanced chemical reaction does not necessarily reveal either the individual elementary reactions by which a reaction occurs or its rate law. A reaction mechanism is the microscopic path by which reactants are transformed into products. Each step is an elementary reaction. Species that are formed in one step and consumed in another are intermediates. Each elementary reaction can be described in terms of its molecularity, the number of molecules that collide in that step. The slowest step in a reaction mechanism is the rate-determining step.