10.1: A Network Solid - Diamond

- Page ID

- 189668

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Some materials don't fall into any of the categories that we have seen so far. They are not metals, so they can't be described as lattices of identical ions surrounded by delocalized electrons. They are not ionic solids, so they can't be thought of as arrays of one type of ion with the counterions packed into the interstitial holes to balance the charge. They are not molecules, so we wouldn't draw them as discrete, self-contained collections of connected atoms.

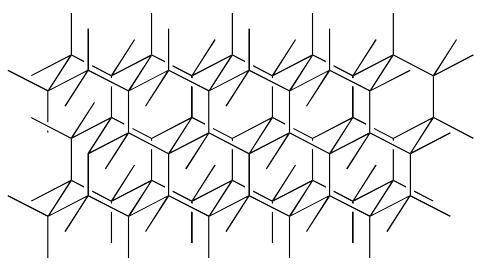

Diamond, for example, is a network solid. Diamond is an allotrope of carbon - it is one of several forms of elemental carbon found in nature. It looks something like this, on an atomic scale. The lines are bonds between the carbon atoms. Each carbon atom makes four bonds, one to each of four different neighbors.

Diamond is composed entirely of carbon atoms, but carbon is too electronegative to allow its electrons to completely delocalize into an electron sea, like metallic elements do. It forms a crystalline, solid structure, but it does not dissolve even a tiny bit in water like ionic compounds would, because it has no ions to form ion-dipole interactions with the water molecules. It forms covalent bonds with its neighboring atoms, sharing these electrons rather than exchanging them, but it forms an extended solid rather than individual units.

- Network solids are like molecules because they have covalent bonds connecting their atoms.

- Network solids are unlike molecules because they don't have a limited or specific size; their structures can extend "seemingly forever" on the atomic scale.

What do most people know about diamonds? They are very expensive, of course. They are very shiny. They are very, very hard. In fact, there is a scale used by minerologists to describe the hardness of materials called "Mohs scale of hardness". The scale was developed by German geologist Friedrich Mohs in the early 1800's. It simply places ten different minerals in order from softest to hardest and assigns each of them a number. Diamond is a 10, meaning it is the hardest material on the scale. Diamond is, in fact, the hardest naturally-ocurring substance in the world.

| Mineral | Hardness |

|---|---|

| talc | 1 |

| gypsum | 2 |

| calcite | 3 |

| fluorite | 4 |

| apatite | 5 |

| orthoclase | 6 |

| quartz | 7 |

| topaz | 8 |

| corundum | 9 |

| diamond | 10 |

Mohs scale is qualitative, not quantitative; each mineral in the scale is harder than the one before it. Mohs scale has been widely used by field geologists because of its simplicity. If you pick up a mineral and can scratch it with that diamond you keep in your toolbox, but the corundum does not leave a mark, then the hardness of the new sample is around 9.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Rank the following minerals using Mohs scale.

- graphite, which scratches talc but is itself scratched by gypsum

- stishovite, which can scratch corundum but not diamond; diamond scratches stishovite

- opal, which scratches orthoclase and fluorite but not quartz or topaz

- obsidian, which can be scratched by quartz and orthoclase but not apatite; obsidian does not scratch apatite, either

- ruby, which is scratched by diamond; however, neither corundum nor ruby can scratch each other.

- emerald, which can be scratched by ruby and topaz but scratches quartz

- Answer a:

-

graphite is between 1 & 2

- Answer b:

-

stishovite is between 9 & 10

- Answer c:

-

opal is between 6 & 7

- Answer d:

-

obsidian is about 5

- Answer e:

-

ruby is about 9

- Answer f:

-

emerald is between 7 & 8

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

"Absolute hardness" can be measured in a number of ways. For example, a sample can be scored by a diamond needle using carefully controlled pressure, and the width or depth of the score can be measured to get a quantitative comparison of the hardness of different materials.

Plot the hardness of each material according to Mohs scale on the x axis and the hardness determined by a sclerometer test to see the relationship between Mohs scale and absolute hardness.

|

material |

hardness |

|---|---|

| talc | 1 |

| gypsum | 3 |

| calcite | 9 |

| fluorite | 21 |

| apatite | 48 |

| orthoclase | 72 |

| quartz | 100 |

| topaz | 200 |

| corundum | 400 |

| diamond | 1600 |

What makes diamond so hard? Let's compare it to a few of the softer minerals in the scale. Gypsum is a crystalline hydrate of calcium sulfate: CaSO4.2H2O. Calcite is a mineral form of calcium carbonate: CaCO3. Fluorite is composed of calcium fluoride: CaF2.

These materials are all ionic solids. Gypsum contains calcium cations and sulfate anions, as well as bound water. Calcite contains calcium ions and carbonate ions. Fluorite contains calcium ions and fluoride ions. Surely the ionic bonds that hold these ions together are very strong. Why can they be deformed and scratched?

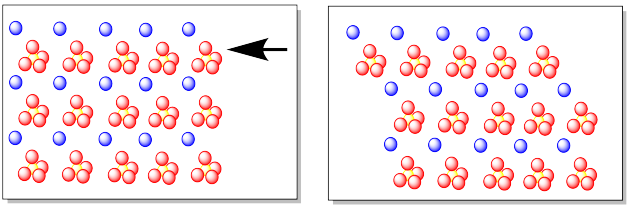

An ionic bond is not directional. It does not matter whether a sulfate ion is above or below a calcium ion, or to the left or the right of it. The attraction between the ions is still the same.

If we imagine a shearing force on a crystal of calcium sulfate, meaning that we are pushing against only one layer of the crystalline material, then we might see that layer slide in response to the force. As the ions in that layer slide, they begin to lose their attraction to the ions in the layer beneath them, but then they become attracted to new ions that are sliding towards. When we are finished, we still have an ionic solid in which ions are atracted to counterions around them, but the partners have changed.

We can't do that in diamond because the carbon atoms are all covalently bonded to each other. The electrons in those bonds appear to be localized in particular regions of space around the carbon atoms, making a framework of tetrahedra. That strong framework holds each carbon atom in place with four bonds, so that it is difficult to displace any one atom or layer of atoms.

Silicon: an analog of carbon

Silicon is found below carbon in the periodic table. Consequently, it has some chemical similarities with its neighbor. For example, pure silicon adopts a structure that is very similar to that of diamond.

Elemental silicon, Si, is indispensable for modern electronics because, in the presence of trace impurities, it has semiconducting properties. However, elemental silicon really does not exist in nature. It must go through chemical reduction from silica, SiO2, in an electric arc furnace:

\[\ce{SiO2 + 2C -> Si + 2CO}\]

The resulting silicon is painstakingly purified by a number of chemical processes. For example, it can be converted to SiCl4, which is then purified repeatedly via distillation to remove trace impurities, then turned back into silicon by reduction with zinc:

\[\ce{SiCl4 + 2Zn -> Si + 2 ZnCl2}\]

One of the final steps is recrystallization of the silicon from its molten phase. A rod with a small "seed" of pure silicon is dipped into the molten silicon and slowly drawn upwards. As the molten silicon cools against the cooler surface of the rod, it recrystallizes. The rod is pulled slowly upward, and pure silicon continues to grow on the cooler, crystalline silicon being pulled from the melt, forming a long crystal.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Draw the structure of elemental silicon.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\)

Silicone is not the same thing as silicon. Silicone is a class of polymer. It exists as long, flexible chains in which the same group of atoms is repeated over and over. There are lots of kinds of silicone, but one example of a silicone formula is ((CH3)2SiO)n. The subscript n means the unit in parentheses is repeated over and over in a chain.

- Draw a section of silicone several units long.

- Explain how the structures of silicon and silicone might give them very different physical properties.