2.2: The Environment and its Chemistry

- Page ID

- 284411

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

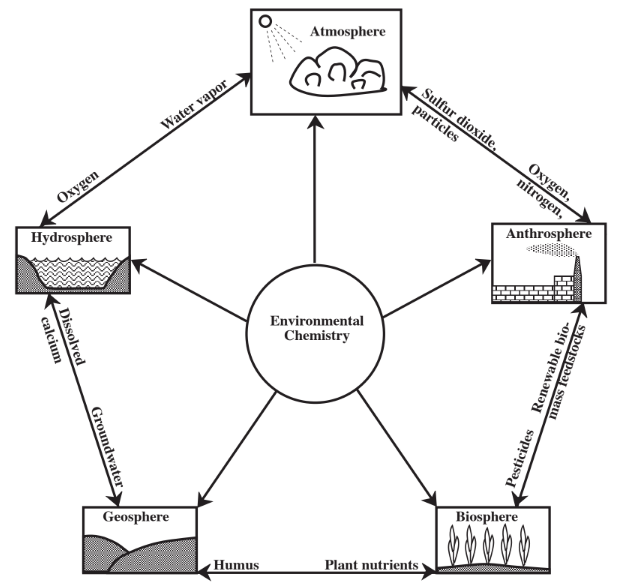

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)It was noted in Section 1.2 that, the environment consists of our surroundings, which may affect us and which, in turn, we may affect. Obviously the chemical nature and processes of matter in the environment are important. Compared to the generally well defined processes that chemists study in the laboratory, those that occur in the environment are rather complex and must be viewed in terms of simplified models. A large part of this complexity is due to the fact that the environment consists of the five overlapping and interacting spheres — the atmosphere, the hydrosphere, the geosphere, the biosphere, and the anthrosphere mentioned in Section 1.2 and shown from the viewpoint of their chemical interactions in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). In order to better understand the chemistry that occurs in these spheres they are briefly described here.

The atmosphere is a very thin layer compared to the size of Earth, with most atmospheric gases lying within a few kilometers of sea level. In addition to providing oxygen for living organisms, the atmosphere provides carbon dioxide required for plant photosynthesis, and nitrogen that organisms use to make proteins. The atmosphere serves a vital protective function in that it absorbs highly energetic ultraviolet radiation from the sun that would kill living organisms exposed to it. A particularly important part of the atmosphere in this respect is the stratospheric layer of ozone, an ultraviolet-absorbing form of elemental oxygen. Because of its ability to absorb infrared radiation by which Earth loses the energy that it absorbs from the sun, the atmosphere stabilizes Earth’s surface temperature. The atmosphere also serves as the medium by which the solar energy that falls with greatest intensity in equatorial regions is redistributed away from the Equator. It is the medium in which water vapor evaporated from oceans as the first step in the hydrologic cycle is transported over land masses to fall as rain over land.

Earth’s water is contained in the hydrosphere. Although frequent reports of torrential rainstorms and flooded rivers produced by massive storms might give the impression that a large fraction of Earth’s water is fresh water, more than 97% of it is seawater in the oceans. Most of the remaining fresh water is present as ice in polar ice caps and glaciers. A small fraction of the total water is present as vapor in the atmosphere. The remaining liquid fresh water is that available for growing plants and other organisms and for industrial uses. This water may be present on the surface as lakes, reservoirs, and streams, or it may be underground as groundwater.

The solid part of earth, the geosphere, includes all rocks and minerals. A particularly important part of the geosphere is soil, which supports plant growth, the basis of food for all living organisms. The lithosphere is a relatively thin solid layer extending from Earth’s surface to depths of 50–100 km. The even thinner outer skin of the lithosphere known as the crust is composed of relatively lighter silicate-based minerals. It is the part of the geosphere that is available to interact with the other environmental spheres and that is accessible to humans.

The biosphere is composed of all living organisms. For the most part, these organisms live on the surface of the geosphere on soil, or just below the soil surface. The oceans and other bodies of water support high populations of organisms. Some life forms exist at considerable depths on ocean floors. In general, though, the biosphere is a very thin layer at the interface of the geosphere with the atmosphere. The biosphere is involved with the geosphere, hydrosphere, and atmosphere in biogeochemical cycles through which materials such as nitrogen and carbon are circulated.

Through human activities, the anthrosphere, that part of the environment made and operated by humans, has developed strong interactions with the other environmental spheres. Many examples of these interactions could be cited. By cultivating large areas of soil for domestic crops, humans modify the geosphere and influence the kinds of organisms in the biosphere. Humans divert water from its natural flow, use it, sometimes contaminate it, then return it to the hydrosphere. Emissions of particles to the atmosphere by human activities affect visibility and other characteristics of the atmosphere. The emission of large quantities of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere by combustion of fossil fuels may be modifying the heat-absorbing characteristics of the atmosphere to the extent that global warming is almost certainly taking place. The anthrosphere perturbs various biogeochemical cycles.

The effect of the anthrosphere over the last two centuries in areas such as burning large quantities of fossil fuels is especially pronounced upon the atmosphere and has the potential to change the nature of Earth significantly. According to Nobel Laureate Paul J. Crutzen of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, Mainz, Germany, this impact is so great that it will lead to a new global epoch to replace the halocene epoch that has been in effect for the last 10,000 years since the last Ice Age. Dr. Crutzen has coined the term anthropocene (from anthropogenic) to describe the new epoch that is upon us.