Titration of a Weak Polyprotic Acid

- Page ID

- 369

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)An Arrhenius acid donates a proton (\(H^+\)), so a polyprotic acid donates protons. However, a polyprotic acid differs from a monoprotic acid because it has more than one acidic \(H^+\), so it has the ability to donate multiple protons. As a weak polyprotic acid, it does not completely dissociate. Here are some examples of weak polyprotic acids:

- A triprotic acid: \(H_3PO_4\)

- A diprotic acid: \(H_2CO_3\)

- A diprotic acid: \(H_2SO_3\)

Acid Dissociation Constant

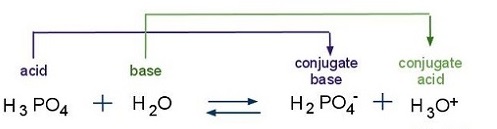

As an acid, a polyprotic acids have a very small acid dissociation constant (\(K_a\)), which measures the strength of the acid. Ka corresponds to the reaction of a weak acid with water and can be used to determine the pH of a solution. In the figure below, water serves as the base because it accepts a proton, H+, from the phosphoric acid to become a hydronium ion. Phosphoric acid becomes a conjugate base because it loses a proton.

The acid dissociation constant can be attained by the following equation:

\[ K_a=\dfrac{\text{Concentration of Products}}{\text{Concentration of Reactants}} \nonumber\]

or even by acid dissociation constant at a logarithmic scale, also known as pKa:

\[ pK_a=-\log_{10}K_a \label{1}\]

The equation can be manipulated into

\[ K_a=10^{-pK_a} \label{2}\]

\(pK_a\) also be used to determine the pH of a solution given the concentrations of the conjugate base and undissociated acid. The equation is as follows:

\[ pH=pK_a+\log\dfrac{[A^-]}{[HA]} \label{3}\]

with \( {A^-}\) is the conjugate base and \( HA\) is the undissociated acid.

There are as many acid ionization constants as there are acidic protons. For example, the ionization steps for phosphoric acid with ionization constants are

\[H_{3}PO_{4}+H_{2}O \rightleftharpoons H_{3}O^++H_{2}PO_{4}^-\]

with \[{K_{a1}}=\dfrac{[H_{3}O^+][H_{2}PO_{4}^-]}{[H_{3}PO_{4}]}=6.9 \times 10^{-3}\]

\[H_{2}PO_{4}^-+H_{2}O \rightleftharpoons H_{3}O^+ + HPO_{4}^ {2-}\]

with \[{K_{a2}}=\dfrac{[H_{3}O^+][HPO_{4}^{2-}]}{[H_{2}PO_{4}^-]}=6.2\times 10^{-8}\]

\[HPO_{4}^{2-}+H_{2}O \rightleftharpoons H_{3}O^+ + PO_{4}^ {3-}\]

with \[{K_{a3}}=\dfrac{[H_{3}O^+][PO_{4}^{3-}]}{[HPO_{4}^{2-}]}=4.8 \times 10^{-13}\]

Note that the acid dissociation constant of the first proton, indicated by \(K_{a1}\), is the largest of all the successive acid dissociation constants. Acid dissociation constants, along with information from a titration, give the information needed to determine the pH of the solution.

Titration

The purpose of titration is to find the concentration of an unknown solution by adding a known volume of a solution with a known concentration to the unknown concentration of a solution. After finding the concentration of this unknown solution, one can find the pH of the solution, given information about the acid dissociation constant(s). Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) below shows the typical lab titration setup prior to adding any titrant to the analyte.

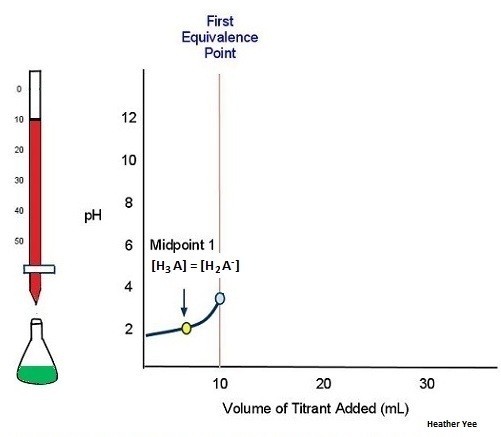

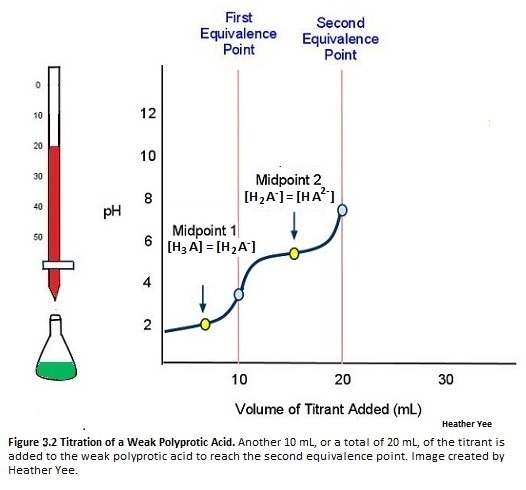

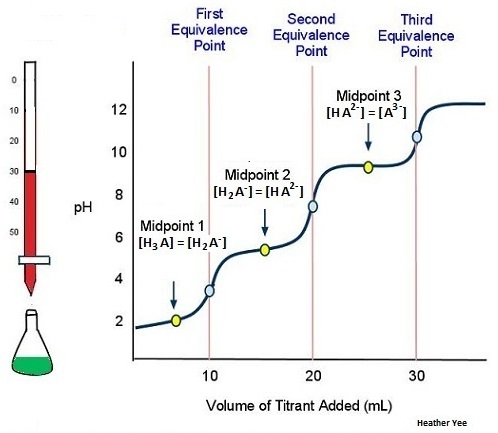

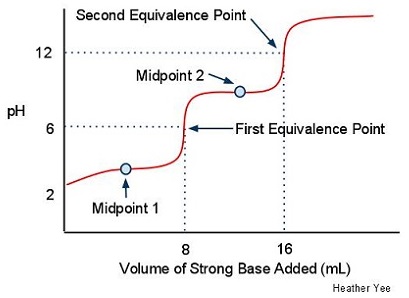

When an acid is titrated, there is an equivalence, or stoichiometric, point, which is when the moles of the strong base added equal of the moles of weak acid present. However, when a weak polyprotic acid is titrated, there are multiple equivalence points because the equivalence point will occur when an H+ is dissociated. Therefore, the number of equivalence points depends on the number of H+ atoms that can be removed from the molecule. Note that when the weak polyprotic acid dissociates, the proton (H+) combines with H2O to form H3O+.

The midpoint, also indicated in the figure, is when the number of moles of strong base added equals half of the moles of the weak acid that are present. For this reason, the midpoint is half of the equivalence point. Notice that there are as many midpoints as there are equivalence points. At the midpoint, pH equals the value of pKa because there is 50:50 mixture of the weak acid and the strong base. To quantify this, the Henderson-Hasselbalch Approximation can be used:

\[ pH=pK_a+log\dfrac{[A^-]}{[HA]} \label{4}\]

Since the solution is a 50/50 mixture, then the concentrations of both A- and HA are equal. Therefore, \( \frac{[A^-]}{[HA]}=1 \). Plugging it back into the original equation, you get \( pH=pK_a+log(1) \). Since \( log(1)=0 \), the equation becomes \( pH=pK_a \).

Titration

This next example shows what occurs when titrating the weak polyprotic acid H3A with a strong base, like LiOH and NaOH. Since there are 3 acidic protons in this example, there is expected to be three equivalence points. (Note: This is disregarding the base used in the titration which would change your products depending upon the base used)

\[ H_{3}A+H_{2}O \rightleftharpoons H_{3}O^++ H_{2}A^- \label{5}\]

As illustrated above in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\), adding 10 mL of the titrant to the weak polyprotic acid is need to reach the first equivalence point.

\[ H_{2}A^-+H_{2}O \rightleftharpoons H_{3}O^++HA^{2-} \label{6} \]

Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\) illustrates that adding another 10 mL (total of 20 mL) to the weak polyprotic acid solution will allow for another H+ to dissociate. Another equivalence points also means yet another midpoint.

\[ HA^{2-}+H_{2}O \rightleftharpoons H_{3}O^++A^{3-} \label{7}\]

In Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\), the titration is finally complete because there are three equivalence points, with the third being attained by adding yet another 10 mL (total of 30 ml) of the titrant.

Attributes of a Weak Polyprotic Acid Titration Curve

The following example below, we can conclude that the graph of a weak polyprotic acid will show not one (as the graph of a weak acid with a strong base titration graph would look), but multiple equivalence points.

- The curve starts at a higher pH than a titration curve of a strong base

- There is a steep climb in pH before the first midpoint

- Gradual increase of pH until past the midpoint.

- Right before the equivalence point there is a sharp increase in pH

- pH steadies itself around the midpoint because the solutions at this point in the curve are buffer solutions, which means that adding small increments of a strong base will only barely change the pH

- Increase in pH near the equivalence point

Problems

- Suppose you titrate the weak polyprotic acid H2CO3 with a strong base, how many equivalence points and midpoints would result?

- How does pH relate to pKa at any point on the titration curve?

- Out of all the acid dissociation constants for the dissociation of the protons for a weak polyprotic acid, which is the largest?

- Given that \( K_{a1}=5.9 \times 10^{-3} \) and \( K_{a2}=6.0 \times 10^{-6} \), calculate the pH after titrating 70 mL of 0.10 M H2SO3 with 50 mL of 0.10 M KOH.

- Consider the titration of 30 mL of 0.10 M H2CO3 with 50 mL of 0.10 LiOH. What would the final pH be if \(K_{a1}=6.0 \times 10^{-3} \) and \( K_{a2}=5.9 \times 10^{-7} \)?

Solutions

- Two equivalence points and two midpoints would result.

- pH relates to pKa in the equation \({pH}=pK_a + \log\dfrac{[A^-]}{[HA]}\) for any point on the titration curve except at the midpoint. At the midpoint \({pH}=pK_a\)

- The acid dissociation constant of the first proton is the largest out of the successive protons.

- The number of moles of H2SO3 and KOH are

\(mol \; H_{2}SO_{3}=Molarity*Volume=0.10 M*0.07 L=0.007\)

\(mol \; KOH=Molarity*Volume=0.10 M*.05 L=0.005\)

After this titration, 0.002 mol H2SO3 remain and 0.005 mol HSO3- form.

\(H_{2}SO_{3}+H_{2}O \rightleftharpoons H_{3}O^++HSO_{3}^{-}\)

\(K_{a1}=\dfrac{[H_{3}O^+][HSO_{3}^{-}]}{[H_{2}SO_{3}]}=5.9\times 10^{-3}\)

\([H_{3}O^+]=2.36\times 10^{-3}\)

\(pH=-log[H_{3}0^+]=-log(2.36\times 10^{-3})=2.63\)

5. The number of moles of H2SO3 and LiOH are

\(mol \; H_{2}CO_{3}=Molarity*Volume=0.10 M \times 0.03L=0.003\)

\[mol \; LiOH=Molarity*Volume=0.10 M*.05L=0.005\]

After this titration, 0.001 mol HCO3- remain and 0.002 mol CO32- form.

\(HCO_{3}^{-1}+H_{2}O \rightleftharpoons H_{3}O^++CO_{3}^{2-}\)

\(K_{a2}=\dfrac{[H_{3}O^+][CO_{3}^{2-}]}{[HCO_{3}^{-1}]}=5.9\times 10^{-7}\)

\([H_{3}O^+]=2.95\times 10^{-7}\)

\(pH=-log[H_{3}0^+]=-log(2.95\times 10^{-7})=6.53\)

References

- Petrucci, et al. General Chemistry: Principles & Modern Applications. 9th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2007.

- Barnum, Dennis W.; Predicting Acid-Base Titration Curves without Calculations. Journal of Chemical Education 1999, 76 (7), 938.

- Hamann, S. D.; Titration behavior of monoprotic and diprotic acids. Journal of Chemical Education 1970, 47 (9), 658.

Contributors

- Andrew Loberg (UCD), Heather Yee (UCD)