1.2: Taking Measurements

- Page ID

- 341882

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- Express quantities properly, using a number and a unit.

- Identify the number of significant figures in a reported value.

A coffee maker’s instructions tell you to fill the coffee pot with 4 cups of water and to use 3 scoops of coffee. When you follow these instructions, you are measuring. When you visit a doctor’s office, a nurse checks your temperature, height, weight, and perhaps blood pressure (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)); the nurse is also measuring.

Chemists measure the properties of matter and express these measurements as quantities. A quantity is an amount of something and consists of a number and a unit. The number tells us how many (or how much), and the unit tells us what the scale of measurement is. For example, when a distance is reported as “5 kilometers,” we know that the quantity has been expressed in units of kilometers and that the number of kilometers is 5. If you ask a friend how far they walk from home to school, and the friend answers “12” without specifying a unit, you do not know whether your friend walks 12 kilometers, 12 miles, 12 furlongs, or 12 yards. Both a number and a unit must be included to express a quantity properly.

To understand chemistry, we need a clear understanding of the units chemists work with and the rules they follow for expressing numbers. The next two sections examine the rules for expressing numbers.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Identify the number and the unit in each quantity.

- one dozen eggs

- 2.54 centimeters

- a box of pencils

- 88 meters per second

Solution

- The number is one, and the unit is a dozen eggs.

- The number is 2.54, and the unit is centimeter.

- The number 1 is implied because the quantity is only a box. The unit is box of pencils.

- The number is 88, and the unit is meters per second. Note that in this case the unit is actually a combination of two units: meters and seconds.

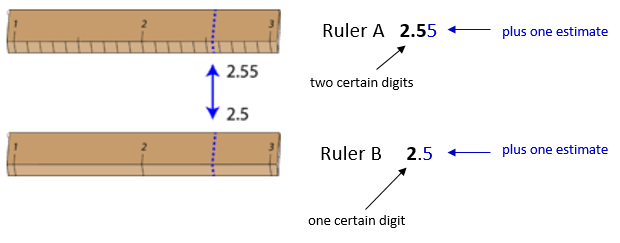

The significant figures in a measurement consist of all the certain digits in that measurement plus one uncertain or estimated digit. In the ruler illustration below, the bottom ruler gave a length with 2 significant figures, while the top ruler gave a length with 3 significant figures. In a correctly reported measurement, the final digit is significant but not certain. Insignificant digits are not reported. With either ruler, it would not be possible to report the length at 2.553cm2.553cm as there is no possible way that the thousandths digit could be estimated. The 3 is not significant and would not be reported.

Measurement Uncertainty

Some error or uncertainty always exists in any measurement. The amount of uncertainty depends both upon the skill of the measurer and upon the quality of the measuring tool. While some balances are capable of measuring masses only to the nearest 0.1g0.1g, other highly sensitive balances are capable of measuring to the nearest 0.001g0.001g or even better. Many measuring tools such as rulers and graduated cylinders have small lines which need to be carefully read in order to make a measurement. Figure 1.2.3 shows two rulers making the same measurement of an object (indicated by the blue arrow).

With either ruler, it is clear that the length of the object is between 22 and 3cm3cm. The bottom ruler contains no millimeter markings. With that ruler, the tenths digit can be estimated and the length may be reported as 2.5cm2.5cm. However, another person may judge that the measurement is 2.4cm2.4cm or perhaps 2.6cm2.6cm. While the 2 is known for certain, the value of the tenths digit is uncertain.

The top ruler contains marks for tenths of a centimeter (millimeters). Now the same object may be measured as 2.55cm2.55cm. The measurer is capable of estimating the hundredths digit because he can be certain that the tenths digit is a 5. Again, another measurer may report the length to be 2.54cm2.54cm or 2.56cm2.56cm. In this case, there are two certain digits (the 2 and the 5), with the hundredths digit being uncertain. Clearly, the top ruler is a superior ruler for measuring lengths as precisely as possible.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

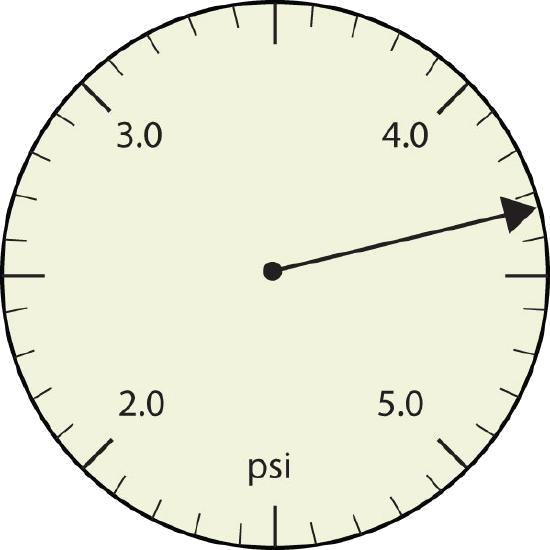

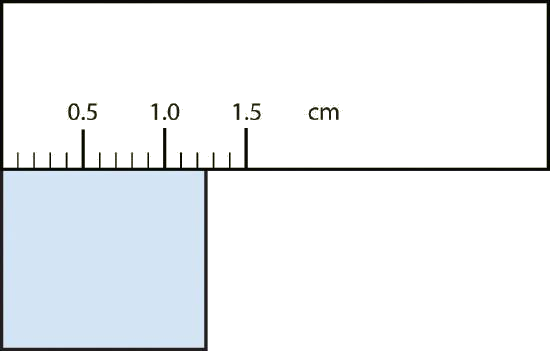

Use each diagram to report a measurement to the proper number of significant figures.

a.

b.

- Answer

-

Explanation Answer a. The arrow is between 4.0 and 5.0, so the measurement is at least 4.0. The arrow is between the third and fourth small tick marks, so it’s at least 0.3. We will have to estimate the last place. It looks like about one-third of the way across the space, so let us estimate the hundredths place as 3. The symbol psi stands for “pounds per square inch” and is a unit of pressure, like air in a tire. The measurement is reported to three significant figures. 4.33 psi b. The rectangle is at least 1.0 cm wide but certainly not 2.0 cm wide, so the first significant digit is 1. The rectangle’s width is past the second tick mark but not the third; if each tick mark represents 0.1, then the rectangle is at least 0.2 in the next significant digit. We have to estimate the next place because there are no markings to guide us. It appears to be about halfway between 0.2 and 0.3, so we will estimate the next place to be a 5. Thus, the measured width of the rectangle is 1.25 cm. The measurement is reported to three significant figures. 1.25 cm

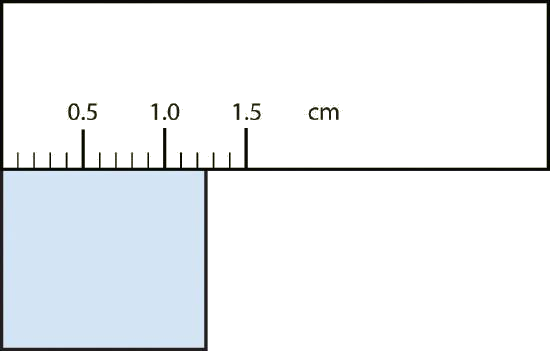

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

What would be the reported width of this rectangle?

- Answer

-

1.25 cm

When you look at a reported measurement, it is necessary to be able to count the number of significant figures. The table below details the rules for determining the number of significant figures in a reported measurement. For the examples in the table, assume that the quantities are correctly reported values of a measured quantity.

| Rule | Examples |

|---|---|

| 1. All nonzero digits in a measurement are significant. |

|

| 2. Zeros that appear between other nonzero digits (middle zeros) are always significant. |

|

| 3. Zeros that appear in front of all of the nonzero digits are called leading zeros. Leading zeros are never significant. |

|

| 4. Zeros that appear after all nonzero digits are called trailing zeros. A number with trailing zeros that lacks a decimal point may or may not be significant. Use scientific notation to indicate the appropriate number of significant figures. |

|

| 5. Trailing zeros in a number with a decimal point are significant. This is true whether the zeros occur before or after the decimal point. |

|

Exact Numbers

Integers obtained either by counting objects or from definitions are exact numbers, which are considered to have infinitely many significant figures. If we have counted four objects, for example, then the number 4 has an infinite number of significant figures (i.e., it represents 4.000…). Similarly, 1 foot (ft) is defined to contain 12 inches (in), so the number 12 in the following equation has infinitely many significant figures:

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

Give the number of significant figures in each. Identify the rule for each.

- 5.87

- 0.031

- 52.90

- 00.2001

- 500

- 6 atoms

Solution

| Explanation | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| a | All three numbers are significant (rule 1). | 5.87, three significant figures |

| b | The leading zeros are not significant (rule 3). The 3 and the 1 are significant (rule 1). | 0.031, two significant figures |

| c | The 5, the 2 and the 9 are significant (rule 1). The trailing zero is also significant (rule 5). | 52.90, four significant figures |

| d | The leading zeros are not significant (rule 3). The 2 and the 1 are significant (rule 1) and the middle zeros are also significant (rule 2). | 00.2001, four significant figures |

| e | The number is ambiguous. It could have one, two or three significant figures. | 500, ambiguous |

| f | The 6 is a counting number. A counting number is an exact number. | 6, infinite |

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Give the number of significant figures in each.

- 36.7 m

- 0.006606 s

- 2,002 kg

- 306,490,000 people

- 3,800 g

- Answer 1

-

Three significant figures

- Answer 2

-

Four significant figures

- Answer 3

-

Four signifcant figures

- Answer 4

-

Infinite (exact number)

- Answer 5

-

Two significant figures

Accuracy and Precision

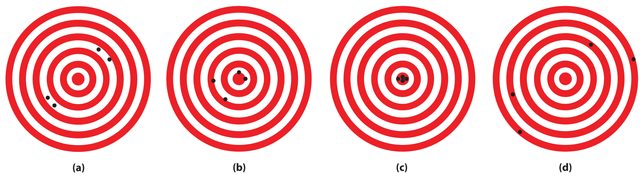

Measurements may be accurate, meaning that the measured value is the same as the true value; they may be precise, meaning that multiple measurements give nearly identical values (i.e., reproducible results); they may be both accurate and precise; or they may be neither accurate nor precise. The goal of scientists is to obtain measured values that are both accurate and precise. The video below demonstrates the concepts of accuracy and precision.

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\)

The following archery targets show marks that represent the results of four sets of measurements.

Which target shows

- a precise, but inaccurate set of measurements?

- a set of measurements that is both precise and accurate?

- a set of measurements that is neither precise nor accurate?

Solution

- Set a is precise, but inaccurate.

- Set c is both precise and accurate.

- Set d is neither precise nor accurate.

Key Take Aways

- Identify a quantity properly with a number and a unit.

- Uncertainty exists in all measurements. The degree of uncertainty is affected in part by the quality of the measuring tool.

- Significant figures give an indication of the certainty of a measurement. Rules allow decisions to be made about how many digits to use in any given situation.

Contributions & Attributions

This page was constructed from content via the following contributor(s) and edited (topically or extensively) by the LibreTexts development team to meet platform style, presentation, and quality:

- CK-12 Foundation by Sharon Bewick, Richard Parsons, Therese Forsythe, Shonna Robinson, and Jean Dupon.

Henry Agnew (UC Davis)

- Sridhar Budhi