1.6: Chemical Equations

- Page ID

- 366567

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Elements

- Derive chemical equations from narrative descriptions of chemical reactions.

- Apply the Law of Conservation of Matter

- Balance a Chemical Equation

How do we represent chemical reactions?

A chemical reaction is a rearrangement of atoms in which one or more compounds are changed into new compounds. All chemical reactions can be represented by equations and models. Since atoms and molecules can not be seen they have to be imagined and that can be quite difficult!

Anytime that atoms separate from each other and recombine into different combinations of atoms, we say a chemical reaction has occurred. No atoms are lost or gained, they are simply rearranged.

Word equations

Note: In mathematic equations, we use an equal sign (=) for example 2 + 2 = 4, but in scientific chemical equations, we use an arrow (→), for example, C + O2→ CO2.

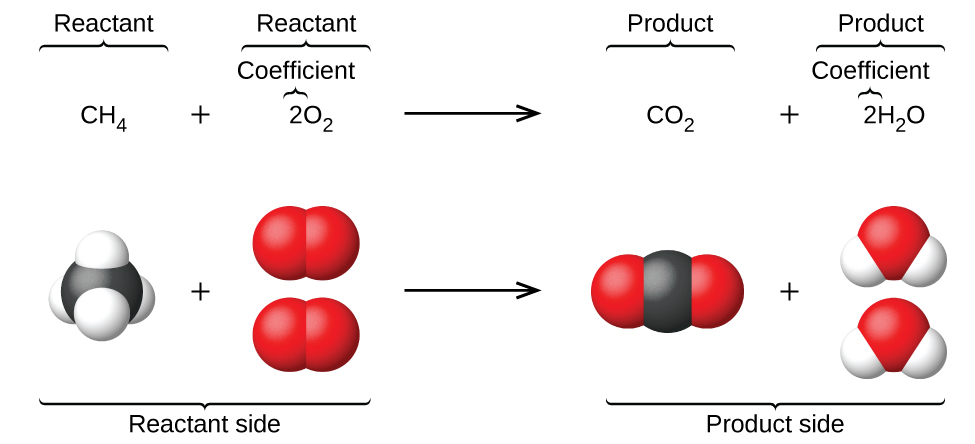

Consider as an example the reaction between one methane molecule (CH4) and two diatomic oxygen molecules (O2) to produce one carbon dioxide molecule (CO2) and two water molecules (H2O). The chemical equation representing this process is provided in the upper half of Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), with space-filling molecular models shown in the lower half of the figure.

This example illustrates the fundamental aspects of any chemical equation:

- The substances undergoing reaction are called reactants, and their formulas are placed on the left side of the equation.

- The substances generated by the reaction are called products, and their formulas are placed on the right sight of the equation.

- Plus signs (+) separate individual reactant and product formulas, and an arrow (⟶) separates the reactant and product (left and right) sides of the equation.

- The relative numbers of reactant and product species are represented by coefficients (numbers placed immediately to the left of each formula). A coefficient of 1 is typically omitted.

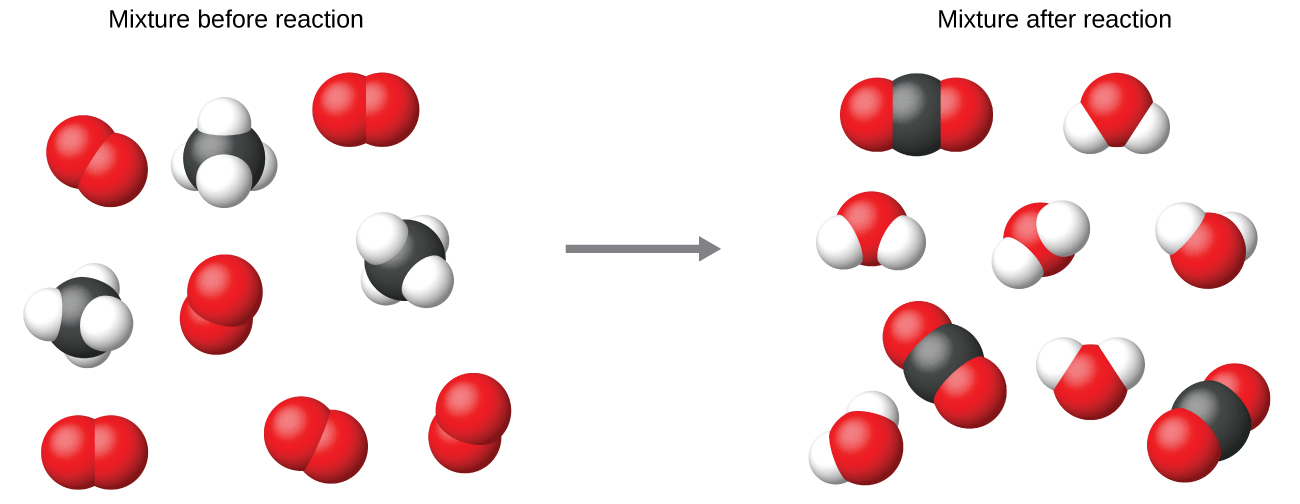

It is common practice to use the smallest possible whole-number coefficients in a chemical equation, as is done in this example. Realize, however, that these coefficients represent the relative numbers of reactants and products, and, therefore, they may be correctly interpreted as ratios. Methane and oxygen react to yield carbon dioxide and water in a 1:2:1:2 ratio. This ratio is satisfied if the numbers of these molecules are, respectively, 1-2-1-2, or 2-4-2-4, or 3-6-3-6, and so on (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). Likewise, these coefficients may be interpreted with regard to any amount (number) unit, and so this equation may be correctly read in many ways, including:

- One methane molecule and two oxygen molecules react to yield one carbon dioxide molecule and two water molecules.

- One dozen methane molecules and two dozen oxygen molecules react to yield one dozen carbon dioxide molecules and two dozen water molecules.

- One mole of methane molecules and 2 moles of oxygen molecules react to yield 1 mole of carbon dioxide molecules and 2 moles of water molecules.

Balancing Equations

When a chemical equation is balanced it means that equal numbers of atoms for each element involved in the reaction are represented on the reactant and product sides. This is a requirement the equation must satisfy to be consistent with the law of conservation of matter. It may be confirmed by simply summing the numbers of atoms on either side of the arrow and comparing these sums to ensure they are equal. Note that the number of atoms for a given element is calculated by multiplying the coefficient of any formula containing that element by the element’s subscript in the formula. If an element appears in more than one formula on a given side of the equation, the number of atoms represented in each must be computed and then added together. For example, both product species in the example reaction, \(\ce{CO2}\) and \(\ce{H2O}\), contain the element oxygen, and so the number of oxygen atoms on the product side of the equation is

\[\left(1\: \cancel{\ce{CO_2} \: \text{molecule}} \times \dfrac{2\: \ce{O} \: \text{atoms}}{ \cancel{\ce{CO_2} \: \text{molecule}}}\right) + \left( \cancel{ \ce{2H_2O} \: \text{molecule} }\times \dfrac{1\: \ce{O}\: \text{atom}}{\cancel{ \ce{H_2O} \: \text{molecule}}}\right)=4\: \ce{O} \: \text{atoms} \nonumber \]

The equation for the reaction between methane and oxygen to yield carbon dioxide and water is confirmed to be balanced per this approach, as shown here:

\[\ce{CH4 +2O2\rightarrow CO2 +2H2O} \nonumber \]

| Element | Reactants | Products | Balanced? |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 1 × 1 = 1 | 1 × 1 = 1 | 1 = 1, yes |

| H | 4 × 1 = 4 | 2 × 2 = 4 | 4 = 4, yes |

| O | 2 × 2 = 4 | (1 × 2) + (2 × 1) = 4 | 4 = 4, yes |

A balanced chemical equation often may be derived from a qualitative description of some chemical reaction by a fairly simple approach known as balancing by inspection. Consider as an example the decomposition of water to yield molecular hydrogen and oxygen. This process is represented qualitatively by an unbalanced chemical equation:

\[\ce{H2O \rightarrow H2 + O2} \tag{unbalanced} \]

Comparing the number of H and O atoms on either side of this equation confirms its imbalance:

| Element | Reactants | Products | Balanced? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H | 1 × 2 = 2 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 2 = 2, yes |

| O | 1 × 1 = 1 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 1 ≠ 2, no |

The numbers of H atoms on the reactant and product sides of the equation are equal, but the numbers of O atoms are not. To achieve balance, the coefficients of the equation may be changed as needed. Keep in mind, of course, that the formula subscripts define, in part, the identity of the substance, and so these cannot be changed without altering the qualitative meaning of the equation. For example, changing the reactant formula from H2O to H2O2 would yield balance in the number of atoms, but doing so also changes the reactant’s identity (it’s now hydrogen peroxide and not water). The O atom balance may be achieved by changing the coefficient for H2O to 2.

\[\ce{2H2O \rightarrow H2 + O2} \tag{unbalanced} \]

| Element | Reactants | Products | Balanced? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H | 2 × 2 = 4 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 4 ≠ 2, no |

| O | 2 × 1 = 2 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 2 = 2, yes |

The H atom balance was upset by this change, but it is easily reestablished by changing the coefficient for the H2 product to 2.

\[\ce{2H_2O \rightarrow 2H2 + O2} \tag{balanced} \]

| Element | Reactants | Products | Balanced? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H | 2 × 2 = 4 | 2 × 2 = 2 | 4 = 4, yes |

| O | 2 × 1 = 2 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 2 = 2, yes |

These coefficients yield equal numbers of both H and O atoms on the reactant and product sides, and the balanced equation is, therefore:

\[\ce{2H_2O \rightarrow 2H_2 + O_2} \nonumber \]

Write a balanced equation for the reaction of molecular nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2) to form dinitrogen pentoxide.

Solution

First, write the unbalanced equation.

\[\ce{N_2 + O_2 \rightarrow N_2O_5} \tag{unbalanced} \]

Next, count the number of each type of atom present in the unbalanced equation.

| Element | Reactants | Products | Balanced? |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1 × 2 = 2 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 2 = 2, yes |

| O | 1 × 2 = 2 | 1 × 5 = 5 | 2 ≠ 5, no |

Though nitrogen is balanced, changes in coefficients are needed to balance the number of oxygen atoms. To balance the number of oxygen atoms, a reasonable first attempt would be to change the coefficients for the O2 and N2O5 to integers that will yield 10 O atoms (the least common multiple for the O atom subscripts in these two formulas).

\[\ce{N_2 + 5 O2 \rightarrow 2 N2O5} \tag{unbalanced} \]

| Element | Reactants | Products | Balanced? |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1 × 2 = 2 | 2 × 2 = 4 | 2 ≠ 4, no |

| O | 5 × 2 = 10 | 2 × 5 = 10 | 10 = 10, yes |

The N atom balance has been upset by this change; it is restored by changing the coefficient for the reactant N2 to 2.

\[\ce{2N_2 + 5O_2\rightarrow 2N_2O_5} \nonumber \]

| Element | Reactants | Products | Balanced? |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 2 × 2 = 4 | 2 × 2 = 4 | 4 = 4, yes |

| O | 5 × 2 = 10 | 2 × 5 = 10 | 10 = 10, yes |

The numbers of N and O atoms on either side of the equation are now equal, and so the equation is balanced.

Write a balanced equation for the decomposition of ammonium nitrate to form molecular nitrogen, molecular oxygen, and water. (Hint: Balance oxygen last, since it is present in more than one molecule on the right side of the equation.)

- Answer

-

\[\ce{2NH4NO3 \rightarrow 2N2 + O2 + 4H2O} \nonumber \]

Use this interactive tutorial for additional practice balancing equations.

Additional Information in Chemical Equations

The physical states of reactants and products in chemical equations very often are indicated with a parenthetical abbreviation following the formulas. Common abbreviations include s for solids, l for liquids, g for gases, and aq for substances dissolved in water (aqueous solutions, as introduced in the preceding chapter). These notations are illustrated in the example equation here:

\[\ce{2Na (s) + 2H2O (l) \rightarrow 2NaOH (aq) + H2(g)} \nonumber \]

This equation represents the reaction that takes place when sodium metal is placed in water. The solid sodium reacts with liquid water to produce molecular hydrogen gas and the ionic compound sodium hydroxide (a solid in pure form, but readily dissolved in water).

Special conditions necessary for a reaction are sometimes designated by writing a word or symbol above or below the equation’s arrow. For example, a reaction carried out by heating may be indicated by the uppercase Greek letter delta (Δ) over the arrow.

\[\ce{CaCO3}(s)\xrightarrow{\:\Delta\:} \ce{CaO}(s)+\ce{CO2}(g) \nonumber \]

Other examples of these special conditions will be encountered in more depth in later chapters.

Key Takeaway

- Chemical equations are symbolic representations of chemical and physical changes.

- Formulas for the substances undergoing the change (reactants) and substances generated by the change (products) are separated by an arrow and preceded by integer coefficients indicating their relative numbers.

- Balanced equations are those whose coefficients result in equal numbers of atoms for each element in the reactants and products.