22.2: Lipids

- Page ID

- 85024

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)On July 11, 2003, the Food and Drug Administration amended its food labeling regulations to require that manufacturers list the amount of trans fatty acids on Nutrition Facts labels of foods and dietary supplements, effective January 1, 2006. This amendment was a response to published studies demonstrating a link between the consumption of trans fatty acids and an increased risk of heart disease. Trans fatty acids are produced in the conversion of liquid oils to solid fats, as in the creation of many commercial margarines and shortenings. They have been shown to increase the levels of low-density lipoproteins (LDLs)—complexes that are often referred to as bad cholesterol—in the blood. In this chapter, you will learn about fatty acids and what is meant by a trans fatty acid, as well as the difference between fats and oils. You will also learn what cholesterol is and why it is an important molecule in the human body.

Fats and oils, found in many of the foods we eat, belong to a class of biomolecules known as lipids. Gram for gram, they pack more than twice the caloric content of carbohydrates: the oxidation of fats and oils supplies about 9 kcal of energy for every gram oxidized, whereas the oxidation of carbohydrates supplies only 4 kcal/g. Although the high caloric content of fats may be bad news for the dieter, it says something about the efficiency of nature’s designs. Our bodies use carbohydrates, primarily in the form of glucose, for our immediate energy needs. Our capacity for storing carbohydrates for later use is limited to tucking away a bit of glycogen in the liver or in muscle tissue. We store our reserve energy in lipid form, which requires far less space than the same amount of energy stored in carbohydrate form. Lipids have other biological functions besides energy storage. They are a major component of the membranes of the 10 trillion cells in our bodies. They serve as protective padding and insulation for vital organs. Furthermore, without lipids in our diets, we would be deficient in the fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K.

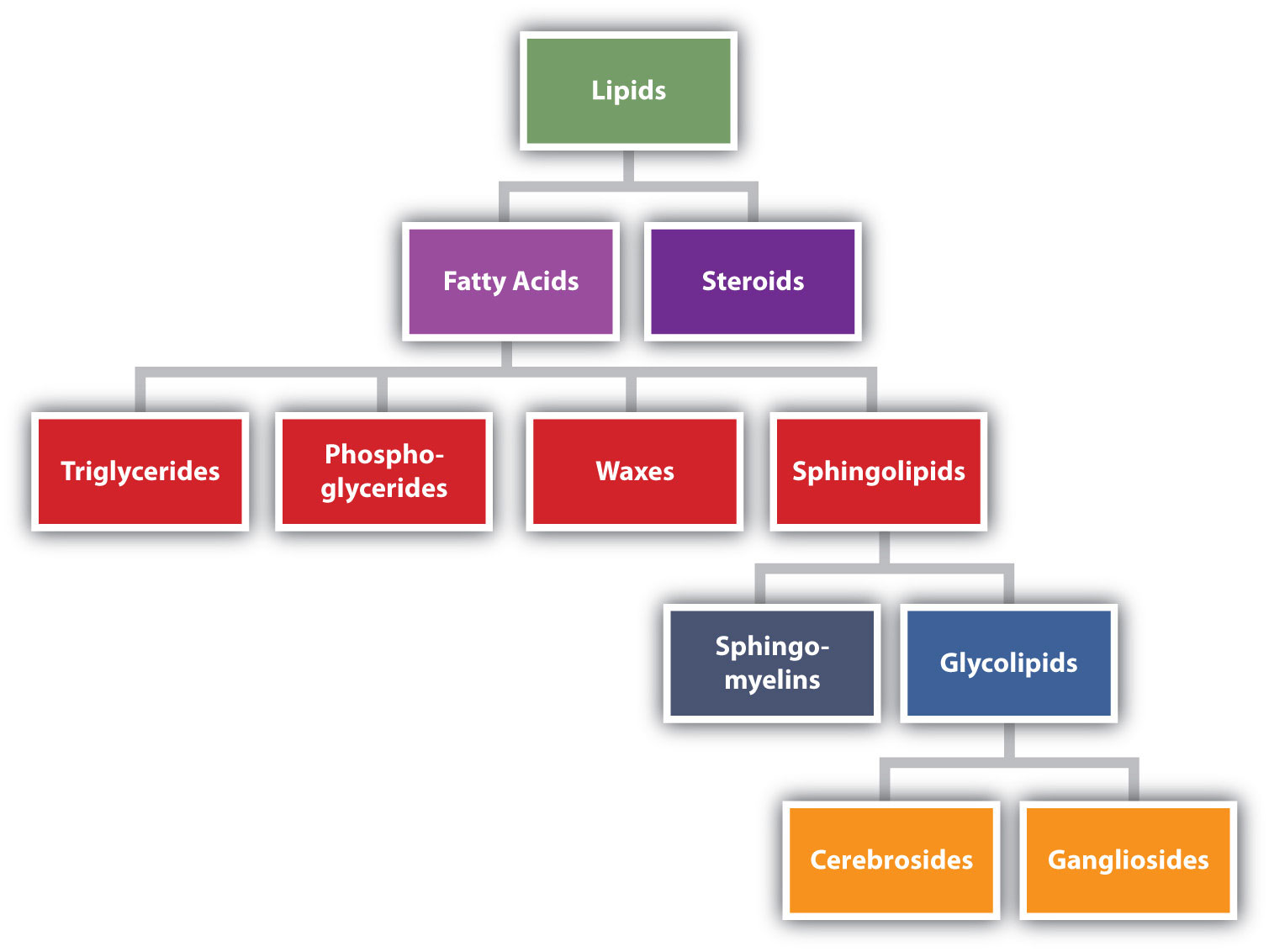

Lipids are not defined by the presence of specific functional groups, as carbohydrates are, but by a physical property—solubility. Compounds isolated from body tissues are classified as lipids if they are more soluble in organic solvents, such as dichloromethane, than in water. By this criterion, the lipid category includes not only fats and oils, which are esters of the trihydroxy alcohol glycerol and fatty acids, but also compounds that incorporate functional groups derived from phosphoric acid, carbohydrates, or amino alcohols, as well as steroid compounds such as cholesterol (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) presents one scheme for classifying the various kinds of lipids). We will discuss the various kinds of lipids by considering one subclass at a time and pointing out structural similarities and differences as we go.

- To recognize the structures of common fatty acids and classify them as saturated, monounsaturated, or polyunsaturated.

Fatty acids are carboxylic acids that are structural components of fats, oils, and all other categories of lipids, except steroids. More than 70 have been identified in nature. They usually contain an even number of carbon atoms (typically 12–20), are generally unbranched, and can be classified by the presence and number of carbon-to-carbon double bonds. Thus, saturated fatty acids contain no carbon-to-carbon double bonds, monounsaturated fatty acids contain one carbon-to-carbon double bond, and polyunsaturated fatty acids contain two or more carbon-to-carbon double bonds.

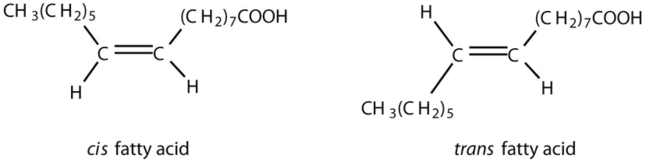

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) lists some common fatty acids and one important source for each. The atoms or groups around the double bonds in unsaturated fatty acids can be arranged in either the cis or trans isomeric form. Naturally occurring fatty acids are generally in the cis configuration.

| Name | Abbreviated Structural Formula | Condensed Structural Formula | Melting Point (°C) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lauric acid | C11H23COOH | CH3(CH2)10COOH | 44 | palm kernel oil |

| myristic acid | C13H27COOH | CH3(CH2)12COOH | 58 | oil of nutmeg |

| palmitic acid | C15H31COOH | CH3(CH2)14COOH | 63 | palm oil |

| palmitoleic acid | C15H29COOH | CH3(CH2)5CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | 0.5 | macadamia oil |

| stearic acid | C17H35COOH | CH3(CH2)16COOH | 70 | cocoa butter |

| oleic acid | C17H33COOH | CH3(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | 16 | olive oil |

| linoleic acid | C17H31COOH | CH3(CH2)3(CH2CH=CH)2(CH2)7COOH | −5 | canola oil |

| α-linolenic acid | C17H29COOH | CH3(CH2CH=CH)3(CH2)7COOH | −11 | flaxseed |

| arachidonic acid | C19H31COOH | CH3(CH2)4(CH2CH=CH)4(CH2)2COOH | −50 | liver |

Two polyunsaturated fatty acids—linoleic and α-linolenic acids—are termed essential fatty acids because humans must obtain them from their diets. Both substances are required for normal growth and development, but the human body does not synthesize them. The body uses linoleic acid to synthesize many of the other unsaturated fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid, a precursor for the synthesis of prostaglandins. In addition, the essential fatty acids are necessary for the efficient transport and metabolism of cholesterol. The average daily diet should contain about 4–6 g of the essential fatty acids.

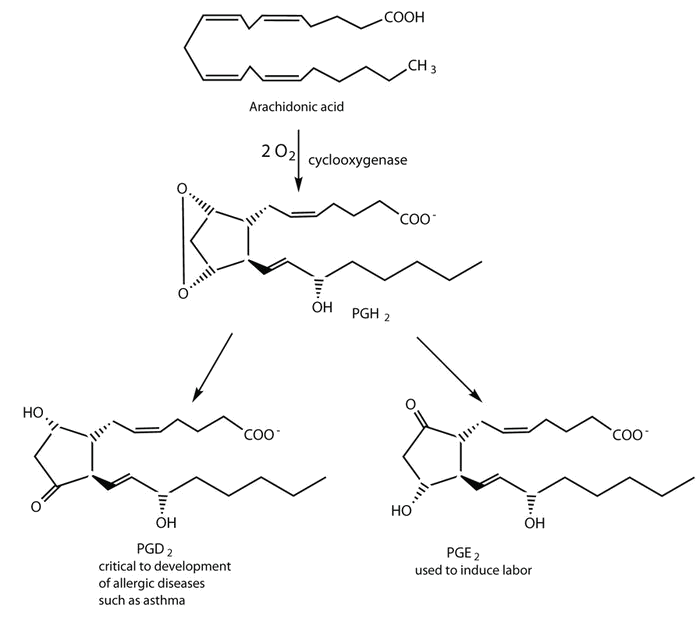

Prostaglandins are chemical messengers synthesized in the cells in which their physiological activity is expressed. They are unsaturated fatty acids containing 20 carbon atoms and are synthesized from arachidonic acid—a polyunsaturated fatty acid—when needed by a particular cell. They are called prostaglandins because they were originally isolated from semen found in the prostate gland. It is now known that they are synthesized in nearly all mammalian tissues and affect almost all organs in the body. The five major classes of prostaglandins are designated as PGA, PGB, PGE, PGF, and PGI. Subscripts are attached at the end of these abbreviations to denote the number of double bonds outside the five-carbon ring in a given prostaglandin.

The prostaglandins are among the most potent biological substances known. Slight structural differences give them highly distinct biological effects; however, all prostaglandins exhibit some ability to induce smooth muscle contraction, lower blood pressure, and contribute to the inflammatory response. Aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, such as ibuprofen, obstruct the synthesis of prostaglandins by inhibiting cyclooxygenase, the enzyme needed for the initial step in the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins.

Their wide range of physiological activity has led to the synthesis of hundreds of prostaglandins and their analogs. Derivatives of PGE2 are now used in the United States to induce labor. Other prostaglandins have been employed clinically to lower or increase blood pressure, inhibit stomach secretions, relieve nasal congestion, relieve asthma, and prevent the formation of blood clots, which are associated with heart attacks and strokes.

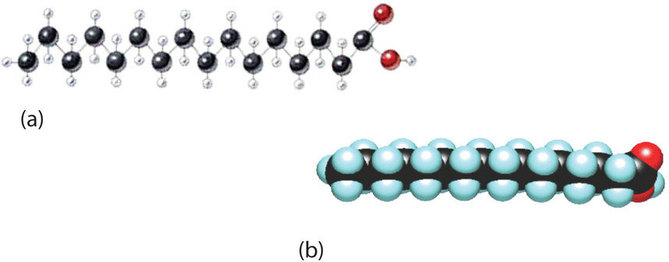

Although we often draw the carbon atoms in a straight line, they actually have more of a zigzag configuration (Figure \(\PageIndex{2a}\)). Viewed as a whole, however, the saturated fatty acid molecule is relatively straight (Figure \(\PageIndex{2b}\)). Such molecules pack closely together into a crystal lattice, maximizing the strength of dispersion forces and causing fatty acids and the fats derived from them to have relatively high melting points. In contrast, each cis carbon-to-carbon double bond in an unsaturated fatty acid produces a pronounced bend in the molecule, so that these molecules do not stack neatly. As a result, the intermolecular attractions of unsaturated fatty acids (and unsaturated fats) are weaker, causing these substances to have lower melting points. Most are liquids at room temperature.

Waxes are esters formed from long-chain fatty acids and long-chain alcohols. Most natural waxes are mixtures of such esters. Plant waxes on the surfaces of leaves, stems, flowers, and fruits protect the plant from dehydration and invasion by harmful microorganisms. Carnauba wax, used extensively in floor waxes, automobile waxes, and furniture polish, is largely myricyl cerotate, obtained from the leaves of certain Brazilian palm trees. Animals also produce waxes that serve as protective coatings, keeping the surfaces of feathers, skin, and hair pliable and water repellent. In fact, if the waxy coating on the feathers of a water bird is dissolved as a result of the bird swimming in an oil slick, the feathers become wet and heavy, and the bird, unable to maintain its buoyancy, drowns.

Summary

Fatty acids are carboxylic acids that are the structural components of many lipids. They may be saturated or unsaturated. Most fatty acids are unbranched and contain an even number of carbon atoms. Unsaturated fatty acids have lower melting points than saturated fatty acids containing the same number of carbon atoms.

- Identify the distinguishing characteristics of membrane lipids.

- Describe membrane components and how they are arranged.

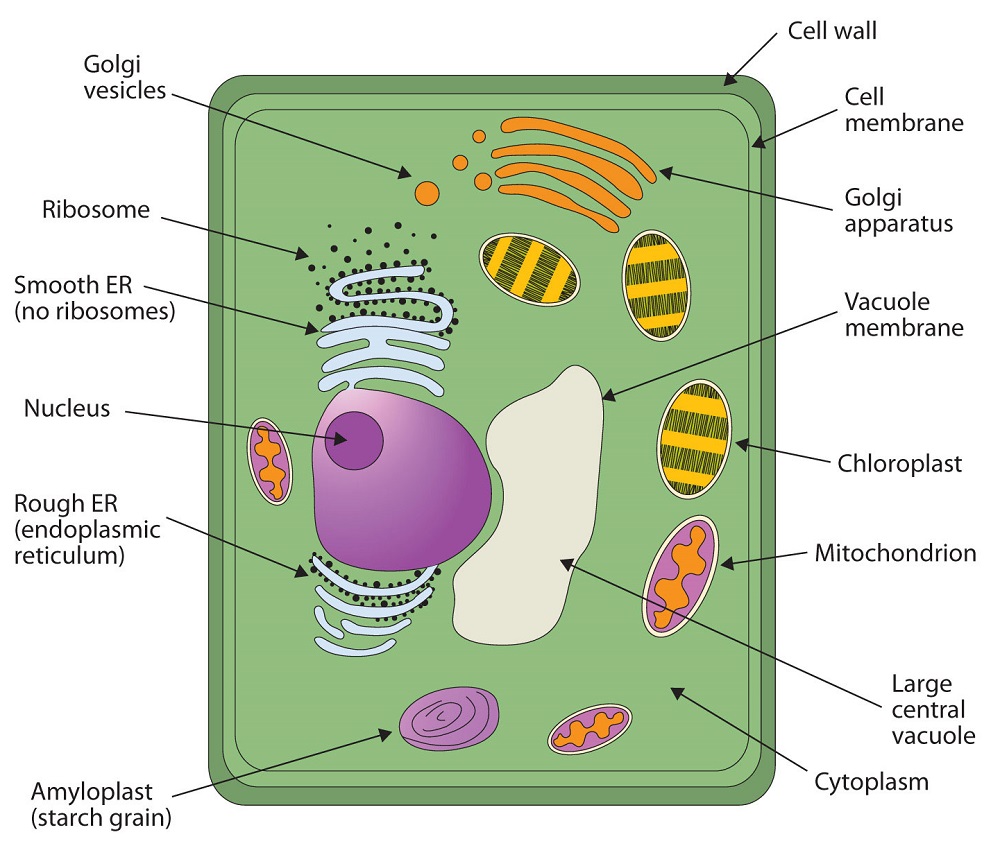

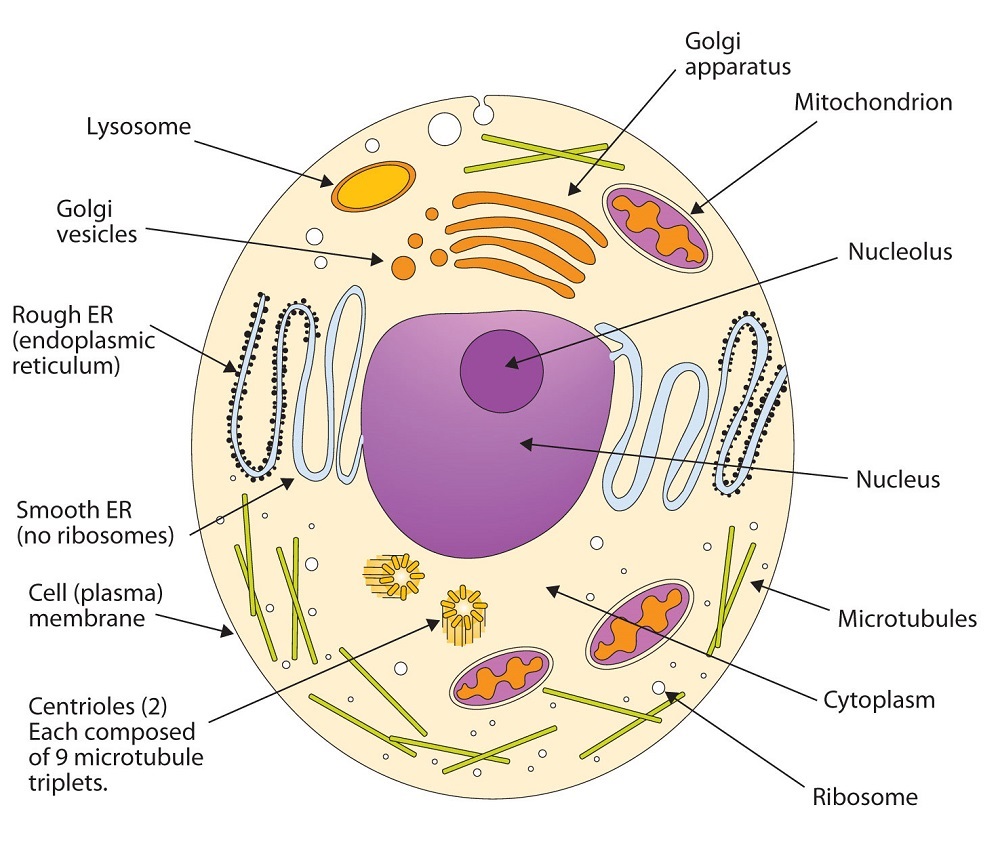

All living cells are surrounded by a cell membrane. Plant cells (Figure \(\PageIndex{1A}\)) and animal cells (Figure \(\PageIndex{1B}\)) contain a cell nucleus that is also surrounded by a membrane and holds the genetic information for the cell. Everything between the cell membrane and the nuclear membrane—including intracellular fluids and various subcellular components such as the mitochondria and ribosomes—is called the cytoplasm. The membranes of all cells have a fundamentally similar structure, but membrane function varies tremendously from one organism to another and even from one cell to another within a single organism. This diversity arises mainly from the presence of different proteins and lipids in the membrane.

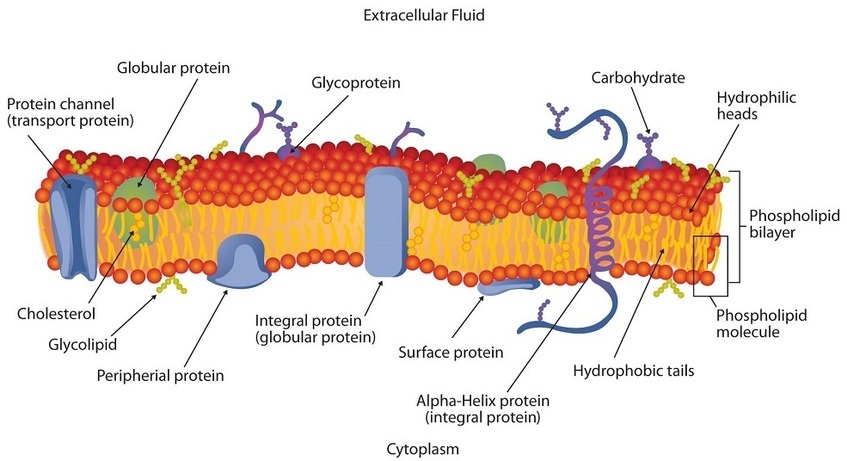

The lipids in cell membranes are highly polar but have dual characteristics: part of the lipid is ionic and therefore dissolves in water, whereas the rest has a hydrocarbon structure and therefore dissolves in nonpolar substances. Often, the ionic part is referred to as hydrophilic, meaning “water loving,” and the nonpolar part as hydrophobic, meaning “water fearing” (repelled by water). When allowed to float freely in water, polar lipids spontaneously cluster together in any one of three arrangements: micelles, monolayers, and bilayers (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Micelles are aggregations in which the lipids’ hydrocarbon tails—being hydrophobic—are directed toward the center of the assemblage and away from the surrounding water while the hydrophilic heads are directed outward, in contact with the water. Each micelle may contain thousands of lipid molecules. Polar lipids may also form a monolayer, a layer one molecule thick on the surface of the water. The polar heads face into water, and the nonpolar tails stick up into the air. Bilayers are double layers of lipids arranged so that the hydrophobic tails are sandwiched between an inner surface and an outer surface consisting of hydrophilic heads. The hydrophilic heads are in contact with water on either side of the bilayer, whereas the tails, sequestered inside the bilayer, are prevented from having contact with the water. Bilayers like this make up every cell membrane (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)).

In the bilayer interior, the hydrophobic tails (that is, the fatty acid portions of lipid molecules) interact by means of dispersion forces. The interactions are weakened by the presence of unsaturated fatty acids. As a result, the membrane components are free to mill about to some extent, and the membrane is described as fluid.

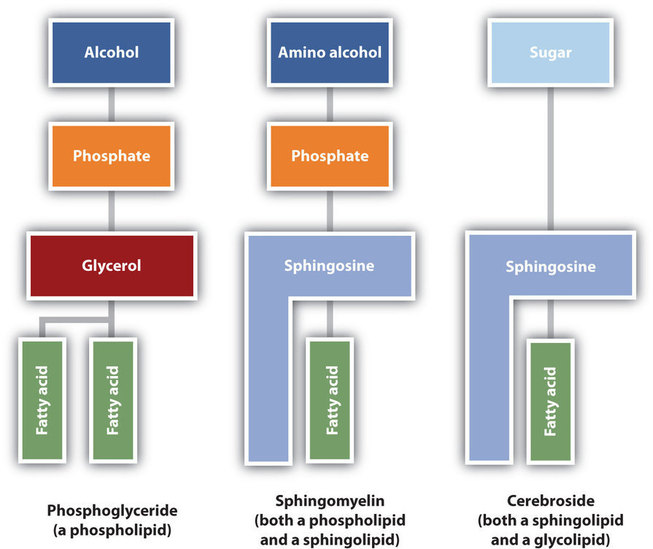

The lipids found in cell membranes can be categorized in various ways. Phospholipids are lipids containing phosphorus. Glycolipids are sugar-containing lipids. The latter are found exclusively on the outer surface of the cell membrane, acting as distinguishing surface markers for the cell and thus serving in cellular recognition and cell-to-cell communication. Sphingolipids are phospholipids or glycolipids that contain the unsaturated amino alcohol sphingosine rather than glycerol. Diagrammatic structures of representative membrane lipids are presented in Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\).

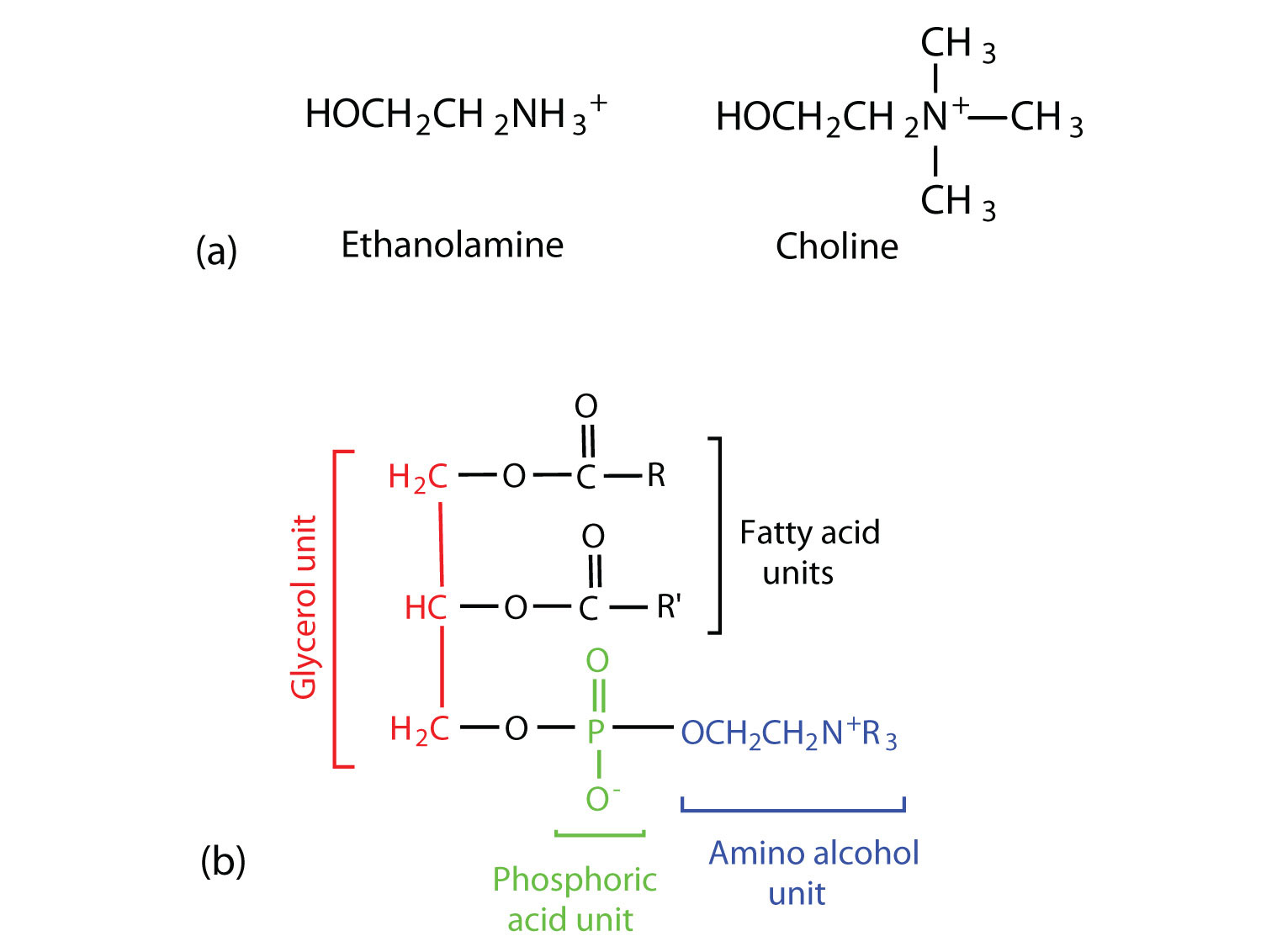

Phosphoglycerides (also known as glycerophospholipids) are the most abundant phospholipids in cell membranes. They consist of a glycerol unit with fatty acids attached to the first two carbon atoms, while a phosphoric acid unit, esterified with an alcohol molecule (usually an amino alcohol, as in part (a) of Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)) is attached to the third carbon atom of glycerol (part (b) of Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). Notice that the phosphoglyceride molecule is identical to a triglyceride up to the phosphoric acid unit (part (b) of Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)).

There are two common types of phosphoglycerides. Phosphoglycerides containing ethanolamine as the amino alcohol are called phosphatidylethanolamines or cephalins. Cephalins are found in brain tissue and nerves and also have a role in blood clotting. Phosphoglycerides containing choline as the amino alcohol unit are called phosphatidylcholines or lecithins. Lecithins occur in all living organisms. Like cephalins, they are important constituents of nerve and brain tissue. Egg yolks are especially rich in lecithins. Commercial-grade lecithins isolated from soybeans are widely used in foods as emulsifying agents. An emulsifying agent is used to stabilize an emulsion—a dispersion of two liquids that do not normally mix, such as oil and water. Many foods are emulsions. Milk is an emulsion of butterfat in water. The emulsifying agent in milk is a protein called casein. Mayonnaise is an emulsion of salad oil in water, stabilized by lecithins present in egg yolk.

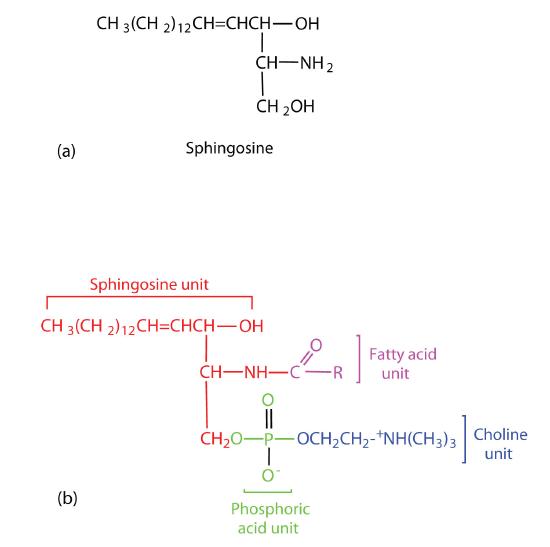

Sphingomyelins, the simplest sphingolipids, each contain a fatty acid, a phosphoric acid, sphingosine, and choline (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)). Because they contain phosphoric acid, they are also classified as phospholipids. Sphingomyelins are important constituents of the myelin sheath surrounding the axon of a nerve cell. Multiple sclerosis is one of several diseases resulting from damage to the myelin sheath.

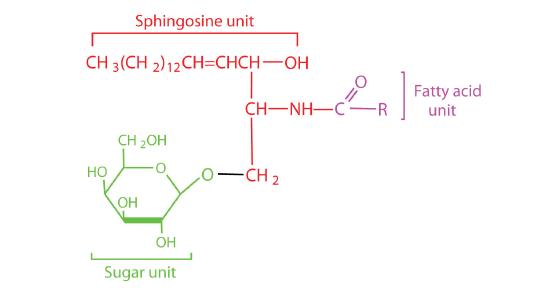

Most animal cells contain sphingolipids called cerebrosides (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)). Cerebrosides are composed of sphingosine, a fatty acid, and galactose or glucose. They therefore resemble sphingomyelins but have a sugar unit in place of the choline phosphate group. Cerebrosides are important constituents of the membranes of nerve and brain cells.

The sphingolipids called gangliosides are more complex, usually containing a branched chain of three to eight monosaccharides and/or substituted sugars. Because of considerable variation in their sugar components, about 130 varieties of gangliosides have been identified. Most cell-to-cell recognition and communication processes (e.g., blood group antigens) depend on differences in the sequences of sugars in these compounds. Gangliosides are most prevalent in the outer membranes of nerve cells, although they also occur in smaller quantities in the outer membranes of most other cells. Because cerebrosides and gangliosides contain sugar groups, they are also classified as glycolipids.

Membrane Proteins

If membranes were composed only of lipids, very few ions or polar molecules could pass through their hydrophobic “sandwich filling” to enter or leave any cell. However, certain charged and polar species do cross the membrane, aided by proteins that move about in the lipid bilayer. The two major classes of proteins in the cell membrane are integral proteins, which span the hydrophobic interior of the bilayer, and peripheral proteins, which are more loosely associated with the surface of the lipid bilayer (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). Peripheral proteins may be attached to integral proteins, to the polar head groups of phospholipids, or to both by hydrogen bonding and electrostatic forces.

Small ions and molecules soluble in water enter and leave the cell by way of channels through the integral proteins. Some proteins, called carrier proteins, facilitate the passage of certain molecules, such as hormones and neurotransmitters, by specific interactions between the protein and the molecule being transported.

Summary

Lipids are important components of biological membranes. These lipids have dual characteristics: part of the molecule is hydrophilic, and part of the molecule is hydrophobic. Membrane lipids may be classified as phospholipids, glycolipids, and/or sphingolipids. Proteins are another important component of biological membranes. Integral proteins span the lipid bilayer, while peripheral proteins are more loosely associated with the surface of the membrane.