6.1 Carbocations

- Page ID

- 17125

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)A carbocation is an ion with a positively-charged carbon atom. Among the simplest examples are methenium CH3+, methanium CH5+, and ethanium C2H7+. Some carbocations may have two or more positive charges, on the same carbon atom or on different atoms; such as the ethylene dication C2H42+.[1]

Definitions

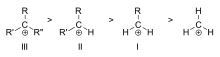

Until the early 1970s, all carbocations were called carbonium ions.[2] In present-day chemistry, a carbocation is any positively charged carbon atom, classified in two main categories according to the valence of the charged carbon:

- +3 in carbenium ions (protonated carbenes),

- +5 or +6 in the carbonium ions (protonated alkanes, named by analogy to ammonium).

This nomenclature was proposed by G. A. Olah.[3] University-level textbooks discuss carbocations only as if they are carbenium ions,[4] or discuss carbocations with a fleeting reference to the older phrase of carbonium ion[5] or carbenium and carbonium ions.[6]

History

The history of carbocations dates back to 1891 when G. Merling[8] reported that he added bromine to tropylidene (cycloheptatriene) and then heated the product to obtain a crystalline, water-soluble material, \(C_7H_7Br\). He did not suggest a structure for it; however, Doering and Knox[9] convincingly showed that it was tropylium (cycloheptatrienylium) bromide. This ion is predicted to be aromatic by Hückel's rule.

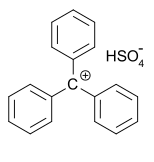

In 1902, Norris and Kehrman independently discovered that colorless triphenylmethanol gives deep-yellow solutions in concentrated sulfuric acid. Triphenylmethyl chloride similarly formed orange complexes with aluminium and tin chlorides. In 1902, Adolf von Baeyer recognized the salt-like character of the compounds formed.

He dubbed the relationship between color and salt formation halochromy, of which malachite green is a prime example.

Carbocations are reactive intermediates in many organic reactions. This idea, first proposed by Julius Stieglitz in 1899,[10] was further developed by Hans Meerwein in his 1922 study[11][12] of the Wagner-Meerwein rearrangement. Carbocations were also found to be involved in the \(S_N1\) reaction, the \(E1\0 reaction, and in rearrangement reactions such as the Whitmore 1,2 shift. The chemical establishment was reluctant to accept the notion of a carbocation and for a long time the Journal of the American Chemical Society refused articles that mentioned them.

The first NMR spectrum of a stable carbocation in solution was published by Doering et al.[13] in 1958. It was the heptamethylbenzenium ion, made by treating hexamethylbenzene with methyl chloride and aluminium chloride. The stable 7-norbornadienyl cation was prepared by Story et al. in 1960[14] by reacting norbornadienyl chloride with silver tetrafluoroborate in sulfur dioxide at −80 °C. The NMR spectrum established that it was non-classically bridged (the first stable non-classical ion observed).

In 1962, Olah directly observed the tert-butyl carbocation by nuclear magnetic resonance as a stable species on dissolving tert-butyl fluoride in magic acid. The NMR of the norbornyl cation was first reported by Schleyer et al.[15] and it was shown to undergo proton-scrambling over a barrier by Saunders et al.[16]

Structure and properties

The charged carbon atom in a carbocation is a "sextet", i.e. it has only six electrons in its outer valence shell instead of the eight valence electrons that ensures maximum stability (octet rule). Therefore, carbocations are often reactive, seeking to fill the octet of valence electrons as well as regain a neutral charge. One could reasonably assume a carbocation to have \(sp^3\) hybridization with an empty \(sp_3\) orbital giving positive charge. However, the reactivity of a carbocation more closely resembles \(sp^2\) hybridization with atrigonal planar molecular geometry. An example is the methyl cation, \(CH_3^+\).

Carbocations are often the target of nucleophilic attack by nucleophiles like hydroxide (OH−) ions or halogen ions.

Carbocations typically undergo rearrangement reactions from less stable structures to equally stable or more stable ones with rate constants in excess of 109/sec. This fact complicates synthetic pathways to many compounds. For example, when 3-pentanol is heated with aqueous HCl, the initially formed 3-pentyl carbocation rearranges to a statistical mixture of the 3-pentyl and 2-pentyl. These cations react with chloride ion to produce about 1/3 3-chloropentane and 2/3 2-chloropentane.

A carbocation may be stabilized by resonance by a carbon-carbon double bond next to the ionized carbon. Such cations as allyl cation CH2=CH–CH2+ and benzyl cation C6H5–CH2+ are more stable than most other carbocations. Molecules that can form allyl or benzyl carbocations are especially reactive. These carbocations where the C+ is adjacent to another carbon atom that has a double or triple bond have extra stability because of the overlap of the empty p orbital of the carbocation with the p orbitals of the π bond. This overlap of the orbitals allows the charge to be shared between multiple atoms – delocalization of the charge - and, therefore, stabilizes the carbocation.

Non-classical ions

Some carbocations such as the norbornyl cation exhibit more or less symmetrical three centre bonding. Cations of this sort have been referred to as non-classical ions. The energy difference between "classical" carbocations and "non-classical" isomers is often very small, and in general there is little, if any, activation energy involved in the transition between "classical" and "non-classical" structures. In essence, the "non-classical" form of the 2-butyl carbocation is 2-butene with a proton directly above the centre of what would be the carbon-carbon double bond. "Non-classical" carbocations were once the subject of great controversy. One of George Olah's greatest contributions to chemistry was resolving this controversy.[17]

Specific carbocations

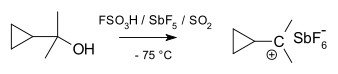

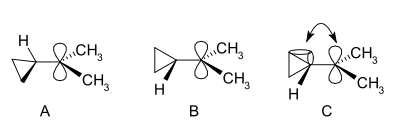

Cyclopropylcarbinyl cations can be studied by NMR:[18][19]

In the NMR spectrum of a dimethyl derivative, two nonequivalent signals are found for the two methyl groups, indicating that the molecular conformation of this cation not perpendicular (as in A) but is bisected (as in B) with the empty p-orbital and the cyclopropyl ring system in the same plane:

In terms of bent bond theory, this preference is explained by assuming favorable orbital overlap between the filled cyclopropane bent bonds and the empty p-orbital.[20]

References

- Hansjörg Grützmacher, Christina M. Marchand (1997), "Heteroatom stabilized carbenium ions", Coordination Chemistry Reviews, volume 163, pages 287-344. doi:10.1016/S0010-8545(97)00043-X

- Gold Book definition carbonium ion HTML

- George A. Olah (1972), "Stable carbocations. CXVIII. General concept and structure of carbocations based on differentiation of trivalent (classical) carbenium ions from three-center bound penta- of tetracoordinated (nonclassical) carbonium ions. Role of carbocations in electrophilic reactions." Journal of the American Chemical Society, volume 94, issue 3, pages 808–820 doi:10.1021/ja00758a020

- Organic chemistry 5th Ed. John McMurry ISBN 0-534-37617-7

- Organic Chemistry, Fourth Edition Paula Yurkanis Bruice ISBN 0-13-140748-1

- Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart; Wothers, Peter (2001). Organic Chemistry (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.

- Organic Chemistry by Marye Anne Fox and James K. Whitesell ISBN 0-7637-0413-X

- Chem. Ber. 24, 3108 1891

- The Cycloheptatrienylium (Tropylium) Ion W. Von E. Doering and L. H. Knox J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1954; 76(12) pp 3203 - 3206; doi:10.1021/ja01641a027

- On the Constitution of the Salts of Imido-Ethers and other Carbimide Derivatives; Am. Chem. J. 21, 101; ISSN: 0096-4085

- H. Meerwein and K. van Emster, Berichte, 1922, 55, 2500.

- Rzepa, H. S.; Allan, C. S. M. (2010). "Racemization of Isobornyl Chloride via Carbocations: A Nonclassical Look at a Classic Mechanism". Journal of Chemical Education 87 (2): 221. Bibcode:2010JChEd..87..221R. doi:10.1021/ed800058c.

- The 1,1,2,3,4,5,6-heptamethylbenzenonium ion W. von E. Doering and M. Saunders H. G. Boyton, H. W. Earhart, E. F. Wadley and W. R. Edwards G. Laber Tetrahedron Volume 4, Issues 1-2 , 1958, Pages 178-185 doi:10.1016/0040-4020(58)88016-3

- The 7-norbornadienyl carbonium ion Paul R. Story and Martin Saunders J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1960; 82(23) pp 6199 - 6199; doi:10.1021/ja01508a058

- Stable Carbonium Ions. X.1 Direct Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Observation of the 2-Norbornyl Cation Paul von R. Schleyer, William E. Watts, Raymond C. Fort, Melvin B. Comisarow, and George A. Olah J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1964; 86(24) pp 5679 - 5680; doi:10.1021/ja01078a056

- Stable Carbonium Ions. XI.1 The Rate of Hydride Shifts in the 2-Norbornyl Cation Martin Saunders, Paul von R. Schleyer, and George A. Olah J. Am. Chem. Soc.; 1964; 86(24) pp 5680 - 5681; doi:10.1021/ja01078a057

- George A. Olah - Nobel Lecture

- Nuclear magnetic double resonance studies of the dimethylcyclopropylcarbinyl cation. Measurement of the rotation barrier David S. Kabakoff, , Eli. Namanworth J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92 (10), pp 3234–3235 doi:10.1021/ja00713a080

- Stable Carbonium Ions. XVII.1a Cyclopropyl Carbonium Ions and Protonated Cyclopropyl Ketones Charles U. Pittman Jr., George A. Olah J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1965, 87 (22), pp 5123–5132 doi:10.1021/ja00950a026

- F.A. Carey, R.J. Sundberg Advanced Organic Chemistry Part A 2nd Ed.