3.1: Matter

- Page ID

- 177345

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objective

- Learn the basic terms used to describe matter

- To describe the solid, liquid and gas phases.

The definition of chemistry—the study of the interactions of matter with other matter and with energy—uses some terms that should also be defined. We start the study of chemistry by defining some basic terms.

Matter

Matter is anything that has mass and takes up space. A book is matter, a computer is matter, food is matter, and dirt in the ground is matter. Sometimes matter may be difficult to identify. For example, air is matter, but because it is so thin compared to other matter (e.g., a book, a computer, food, and dirt), we sometimes forget that air has mass and takes up space. Things that are not matter include thoughts, ideas, emotions, and hopes.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Which of the following is matter and not matter?

- a hot dog

- love

- a tree

Solution

- A hot dog has mass and takes up space, so it is matter.

- Love is an emotion, and emotions are not matter.

- A tree has mass and takes up space, so it is matter.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Which of the following is matter and not matter?

- the moon

- an idea for a new invention

Answer

- The moon is matter.

- The invention itself may be matter, but the idea for it is not.

States of Matter

Water can take many forms. At low temperatures (below \(0^\text{o} \text{C}\)), it is a solid. When at "normal" temperatures (between \(0^\text{o} \text{C}\) and \(100^\text{o} \text{C}\)), it is a liquid. While at temperatures above \(100^\text{o} \text{C}\), water is a gas (steam). The state the water is in depends upon the temperature. Each state (solid, liquid, and gas) has its own unique set of physical properties. Matter typically exists in one of three states: solid, liquid, or gas.

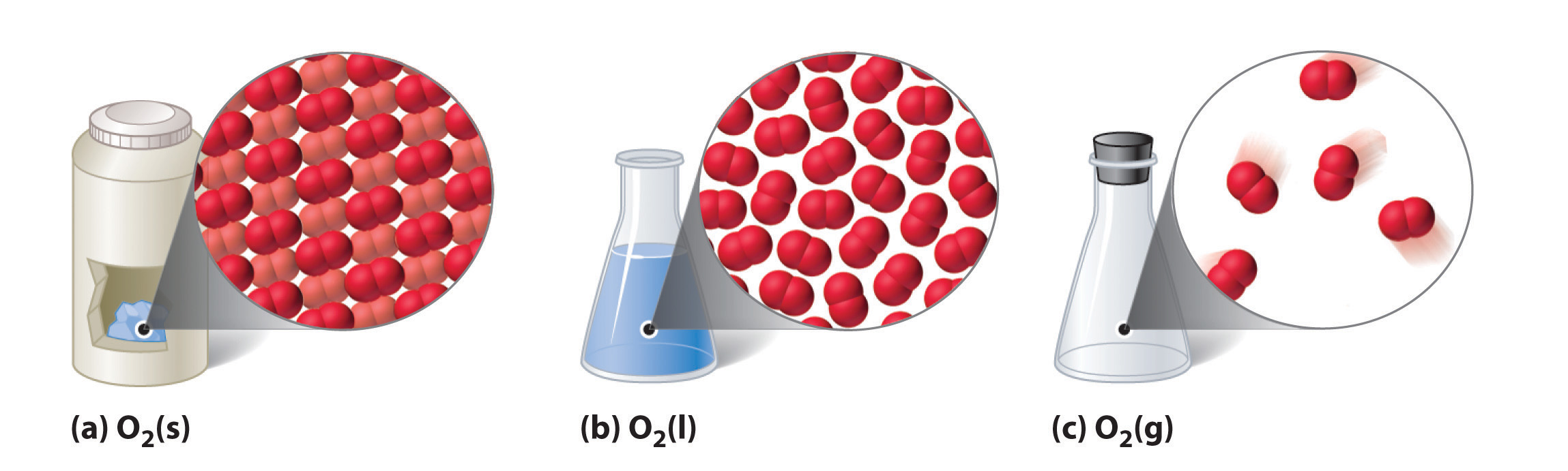

The state a given substance exhibits is also a physical property. Some substances exist as gases at room temperature (oxygen and carbon dioxide), while others, like water and mercury metal, exist as liquids. Most metals exist as solids at room temperature. All substances can exist in any of these three states. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) shows the differences among solids, liquids, and gases at the molecular level. A solid has definite volume and shape, a liquid has a definite volume but no definite shape, and a gas has neither a definite volume nor shape.

Plasma: A Fourth State of Matter

Technically speaking a fourth state of matter called plasma exists, but it does not naturally occur on earth, so we will omit it from our study here.

.jpg?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=197&height=196)

A plasma globe operating in a darkened room. Image used with permission (CC BY-SA 3.0; Chocolateoak).

Solids

In the solid state, the individual particles of a substance are in fixed positions with respect to each other because there is not enough thermal energy to overcome the intermolecular interactions between the particles. As a result, solids have a definite shape and volume. Most solids are hard, but some (like waxes) are relatively soft. Many solids composed of ions can also be quite brittle.

Solids are defined by the following characteristics:

- Definite shape (rigid)

- Definite volume

- Particles vibrate around fixed axes

If we were to cool liquid mercury to its freezing point of \(-39^\text{o} \text{C}\), and under the right pressure conditions, we would notice all of the liquid particles would go into the solid state. Mercury can be solidified when its temperature is brought to its freezing point. However, when returned to room temperature conditions, mercury does not exist in solid state for long, and returns back to its more common liquid form.

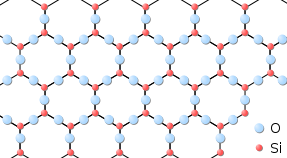

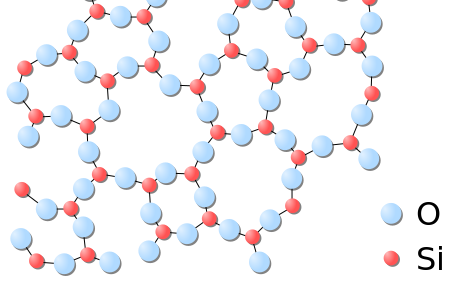

Solids usually have their constituent particles arranged in a regular, three-dimensional array of alternating positive and negative ions called a crystal. The effect of this regular arrangement of particles is sometimes visible macroscopically, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). Some solids, especially those composed of large molecules, cannot easily organize their particles in such regular crystals and exist as amorphous (literally, “without form”) solids. Glass is one example of an amorphous solid.

Liquids

If the particles of a substance have enough energy to partially overcome intermolecular interactions, then the particles can move about each other while remaining in contact. This describes the liquid state. In a liquid, the particles are still in close contact, so liquids have a definite volume. However, because the particles can move about each other rather freely, a liquid has no definite shape and takes a shape dictated by its container.

Liquids have the following characteristics:

- No definite shape (takes the shape of its container)

- Has definite volume

- Particles are free to move over each other, but are still attracted to each other

A familiar liquid is mercury metal. Mercury is an anomaly. It is the only metal we know of that is liquid at room temperature. Mercury also has an ability to stick to itself (surface tension) - a property all liquids exhibit. Mercury has a relatively high surface tension, which makes it very unique. Here you see mercury in its common liquid form.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\): Mercury boiling to become a gas.

If we heat liquid mercury to its boiling point of \(357^\text{o} \text{C}\), and under the right pressure conditions, we would notice all particles in the liquid state go into the gas state.

Gases

If the particles of a substance have enough energy to completely overcome intermolecular interactions, then the particles can separate from each other and move about randomly in space. This describes the gas state, which we will consider in more detail elsewhere. Like liquids, gases have no definite shape, but unlike solids and liquids, gases have no definite volume either. The change from solid to liquid usually does not significantly change the volume of a substance. However, the change from a liquid to a gas significantly increases the volume of a substance, by a factor of 1,000 or more. Gases have the following characteristics:

- No definite shape (takes the shape of its container)

- No definite volume

- Particles move in random motion with little or no attraction to each other

- Highly compressible

| Characteristics | Solids | Liquids | Gases |

|---|---|---|---|

| shape | definite | indefinite | indefinite |

| volume | definite | definite | indefinite |

| relative intermolecular interaction strength | strong | moderate | weak |

| relative particle positions | in contact and fixed in place | in contact but not fixed | not in contact, random positions |

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

What state or states of matter does each statement, describe?

- This state has a definite volume, but no definite shape.

- This state has no definite volume.

- This state allows the individual particles to move about while remaining in contact.

SOLUTION

- This statement describes the liquid state.

- This statement describes the gas state.

- This statement describes the liquid state.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

What state or states of matter does each statement describe?

- This state has individual particles in a fixed position with regard to each other.

- This state has individual particles far apart from each other in space.

- This state has a definite shape.

- Answer a:

- solid

- Answer b:

- gas

- Answer c:

- solid

Key Takeaways

- Chemistry is the study of matter and its interactions with other matter and energy.

- Matter is anything that has mass and takes up space.

- Three states of matter exist - solid, liquid, and gas.

- Solids have a definite shape and volume.

- Liquids have a definite volume, but take the shape of the container.

- Gases have no definite shape or volume.

Contributors

Henry Agnew (UC Davis)