2.02 Expressing Numbers - Significant Figures

- Page ID

- 178115

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between Accuracy and Precision

- Understand the importance of significant figures in measured numbers.

- Identify the number of significant figures in a reported value.

- Use significant figures correctly in arithmetical operations.

Accuracy and Precision

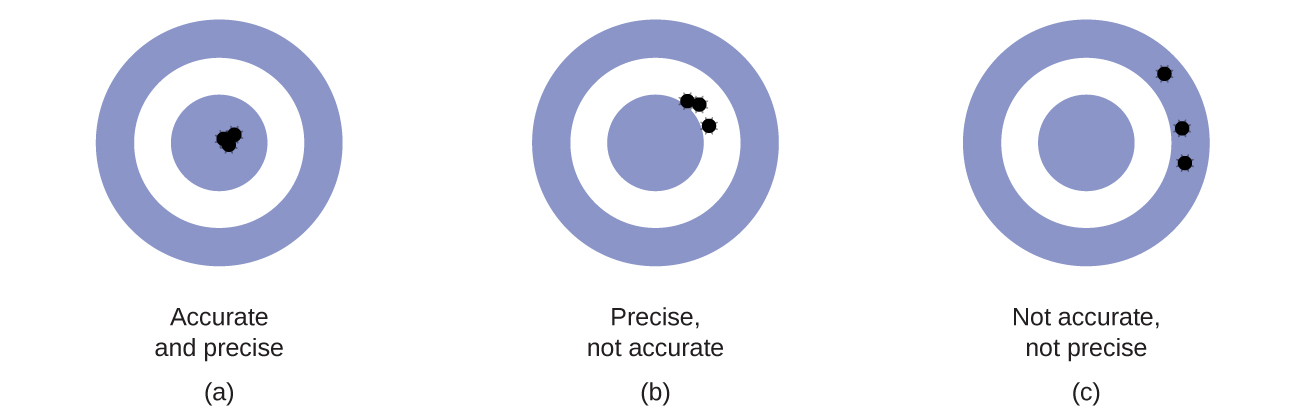

Scientists typically make repeated measurements of a quantity to ensure the quality of their findings and to know both the precision and the accuracy of their results. Measurements are said to be precise if they yield very similar results when repeated in the same manner. A measurement is considered accurate if it yields a result that is very close to the true or accepted value. Precise values agree with each other; accurate values agree with a true value. These characterizations can be extended to other contexts, such as the results of an archery competition (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

Suppose a quality control chemist at a pharmaceutical company is tasked with checking the accuracy and precision of three different machines that are meant to dispense 10 ounces (296 mL) of cough syrup into storage bottles. She proceeds to use each machine to fill five bottles and then carefully determines the actual volume dispensed, obtaining the results tabulated in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\).

| Dispenser #1 | Dispenser #2 | Dispenser #3 |

|---|---|---|

| 283.3 | 298.3 | 296.1 |

| 284.1 | 294.2 | 295.9 |

| 283.9 | 296.0 | 296.1 |

| 284.0 | 297.8 | 296.0 |

| 284.1 | 293.9 | 296.1 |

Considering these results, she will report that dispenser #1 is precise (values all close to one another, within a few tenths of a milliliter) but not accurate (none of the values are close to the target value of 296 mL, each being more than 10 mL too low). Results for dispenser #2 represent improved accuracy (each volume is less than 3 mL away from 296 mL) but worse precision (volumes vary by more than 4 mL). Finally, she can report that dispenser #3 is working well, dispensing cough syrup both accurately (all volumes within 0.1 mL of the target volume) and precisely (volumes differing from each other by no more than 0.2 mL).

Significant Figures

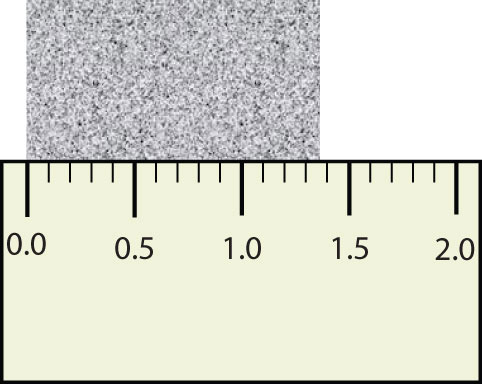

Scientists have established certain conventions for communicating the degree of precision of a measurement, which is dependent on the measuring device used. Imagine, for example, that you are using a meterstick to measure the width of a table. The centimeters (cm) marked on the meterstick, tell you how many centimeters wide the table is. Many metersticks also have markings for millimeters (mm), so we can measure the table to the nearest millimeter. Most metersticks do not have any smaller (or more precise) markings indicated, so you cannot report the measured width of the table any more precise than to the nearest millimeter. However, you can estimate one past the smallest marking, in this case the millimeter, to the next decimal place in the measurement (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

The concept of significant figures takes this limitation into account. The significant figures of a measured quantity are defined as all the digits known with certainty (those indicated by the markings on the measuring device) and the first uncertain, or estimated, digit (one digit past the smallest marking on the measuring device). It makes no sense to report any digits after the first uncertain one, so it is the last digit reported in a measurement. Zeros are used when needed to place the significant figures in their correct positions. Thus, zeros are sometimes counted as significant figures but are sometimes only used as placeholders.

“Sig figs” is a common abbreviation for significant figures.

Consider the earlier example of measuring the width of a table with a meterstick. If the table is measured and reported as being 1,357 mm wide, the number 1,357 has four significant figures. The 1 (thousands place), the 3 (hundreds place), and the 5 (tens place) are certain; the 7 (ones place) is assumed to have been estimated. It would make no sense to report such a measurement as 1,357.0 (five Sig Figs) or 1,357.00 (six Sig Figs) because that would suggest the measuring device was able to determine the width to the nearest tenth or hundredth of a millimeter, when in fact it shows only tens of millimeters and therefore the ones place was estimated.

On the other hand, if a measurement is reported as 150 mm, the 1 (hundreds) and the 5 (tens) are known to be significant, but how do we know whether the zero is or is not significant? The measuring device could have had marks indicating every 100 mm or marks indicating every 10 mm. How can you determine if the zero is significant (the estimated digit), or if the 5 is significant and the zero a value placeholder?

The rules for deciding which digits in a measurement are significant are as follows:

- All nonzero digits are significant. In 1,357 mm, all the digits are significant.

- Sandwiched (or embedded) zeros, those between significant digits, are significant. Thus, 405 g has three significant figures.

- Leading zeros, which are zeros at the beginning of a decimal number less than 1, are not significant. In 0.000458 mL, the first four digits are leading zeros and are not significant. The zeros serve only to put the digits 4, 5, and 8 in the correct decimal positions. This number has three significant figures.

- Trailing zeros, which are zeros at the end of a number, are significant only if the number has a decimal point. Thus, in 1,500 m, the two trailing zeros are not significant because the number is written without a decimal point; the number has two significant figures. However, in 1,500.00 m, all six digits are significant because the number has a decimal point.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

How many significant figures does each number have?

- 6,798,000

- 6,000,798

- 6,000,798.00

- 0.0006798

- Answer a

-

four (by rules 1 and 4)

- Answer b

-

seven (by rules 1 and 2)

- Answer c

-

nine (by rules 1, 2, and 4)

- Answer d

-

four (by rules 1 and 3)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

How many significant figures does each number have?

- 2.1828

- 0.005505

- 55,050

- 5

- 500

Combining Numbers

It is important to be aware of significant figures when you are mathematically manipulating numbers. For example, dividing 125 by 307 on a calculator gives 0.4071661238… to an infinite number of digits. But do the digits in this answer have any practical meaning, especially when you are starting with numbers that have only three significant figures each? It should make sense that the final calculated number can be no more precise than the original numbers used in the calculation. When performing mathematical operations, there are two rules for limiting the number of significant figures in an answer—one rule is for addition and subtraction, and one rule is for multiplication and division.

Significant Figures in Addition and Subtraction

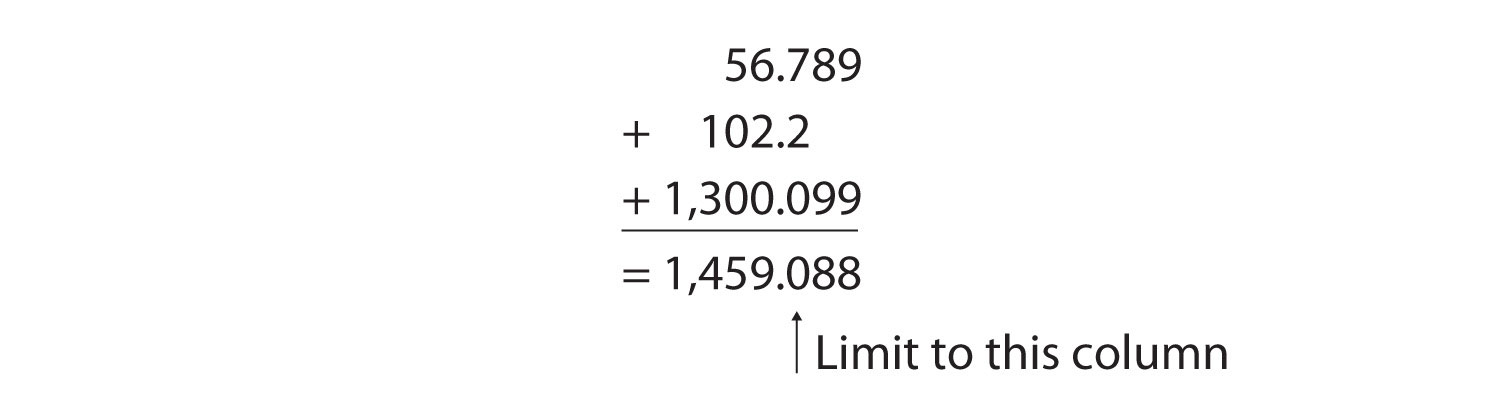

For addition or subtraction, the rule is to stack all the numbers with their decimal points aligned and then limit (round to) the answer’s significant figures to the rightmost column for which all the numbers have significant figures. Consider the following:

The arrow points to the rightmost column in which all the numbers have significant figures—in this case, the tenths place. Therefore, we will limit our final answer to the tenths place. Is our final answer therefore 1,459.0? No, because when we drop digits from the end of a number, we also have to round the number. Notice that the first dropped digit, in the hundredths place, is 8. This suggests that the answer is actually closer to 1,459.1 than it is to 1,459.0, so we need to round up to 1,459.1. The standard rules for rounding numbers are simple: If the first dropped digit is 5 or higher, round up. If the first dropped digit is lower than 5, do not round up.

Significant Figures in Multiplication and Division

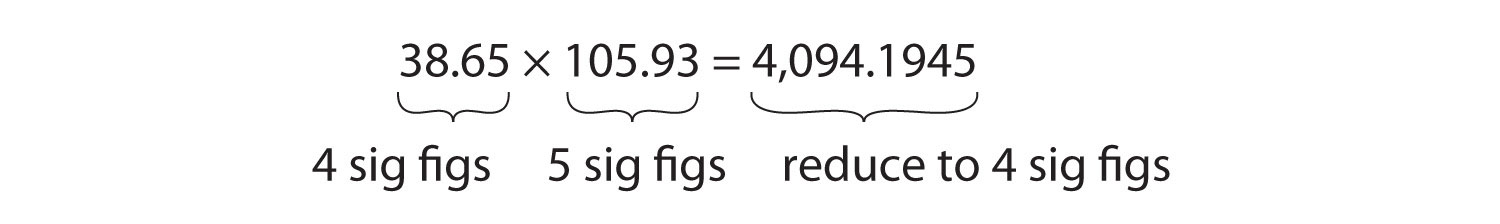

For multiplication or division, the rule is to count the number of significant figures in each number being multiplied or divided and then limit the significant figures in the answer to the lowest count. An example is as follows:

The final answer, limited to four significant figures, is 4,094. The first digit dropped is 1, so we do not round up.

Scientific notation provides a way of communicating significant figures without ambiguity. You simply include all the significant figures in the leading number. For example, the number 450 has two significant figures and would be written in scientific notation as 4.5 × 102, whereas 450.0 has four significant figures and would be written as 4.500 × 102. In scientific notation, all reported digits are significant.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Write the answer for each expression using scientific notation with the appropriate number of significant figures.

- 23.096 × 90.300

- 125 × 9.000

- 1,027 + 610 + 363.06

- Answer a

-

The calculator answer is 2,085.5688, but we need to round it to five significant figures. Because the first digit to be dropped (in the hundredths place) is greater than 5, we round up to 2,085.6, which in scientific notation is 2.0856 × 103.

- Answer b

-

The calculator gives 1,125 as the answer, but we limit it to three significant figures and convert into scientific notation: 1.13 × 103.

- Answer c

-

The calculator gives 2,000.06 as the answer, but because 610 has its farthest-right significant figure in the tens column, our answer must be limited to the tens position: 2.0 × 103.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Write the answer for each expression using scientific notation with the appropriate number of significant figures.

- 217 ÷ 903

- 13.77 + 908.226 + 515

- 255.0 − 99

- 0.00666 × 321

Remember that calculators do not understand significant figures. You are the one who must apply the rules of significant figures to a result from your calculator.

Concept Review Exercises

- Explain why the concept of significant figures is important in scientific measurements.

- State the rules for determining the significant figures in a measurement.

- When do you round a number up, and when do you not round a number up?

Answers

- Significant figures represent all the known digits of a measurement plus the first estimated one. It gives information about how precise the measuring device and measurement is.

- All nonzero digits are significant; zeros between nonzero digits are significant; zeros at the end of a nondecimal number or the beginning of a decimal number are not significant; zeros at the end of a decimal number are significant.

- Round up only if the first digit dropped is 5 or higher.

Key Takeaways

- Significant figures convey the precision of a measurement.

- Significant figures properly report the number of measured and estimated digits in a measurement.

- There are rules for applying significant figures in calculations.