10.4: Water - Both an Acid and a Base

- Page ID

- 218361

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- To write chemical equations for water acting as an acid and as a base.

Water (H2O) is an interesting compound in many respects. Here, we will consider its ability to behave as an acid or a base.

In some circumstances, a water molecule will accept a proton and thus act as a Brønsted-Lowry base. We saw an example in the dissolving of HCl in H2O:

\[\rm{HCl + H_2O_{(ℓ)} \rightarrow H_3O^+_{(aq)} + Cl^−_{(aq)}} \label{Eq1}\]

In other circumstances, a water molecule can donate a proton and thus act as a Brønsted-Lowry acid. For example, in the presence of the amide ion (see Example 4 in Section 10.2), a water molecule donates a proton, making ammonia as a product:

\[H_2O_{(ℓ)} + NH^−_{2(aq)} \rightarrow OH^−_{(aq)} + NH_{3(aq)} \label{Eq2}\]

In this case, NH2− is a Brønsted-Lowry base (the proton acceptor).

So, depending on the circumstances, H2O can act as either a Brønsted-Lowry acid or a Brønsted-Lowry base. Water is not the only substance that can react as an acid in some cases or a base in others, but it is certainly the most common example—and the most important one. A substance that can either donate or accept a proton, depending on the circumstances, is called an amphiprotic compound.

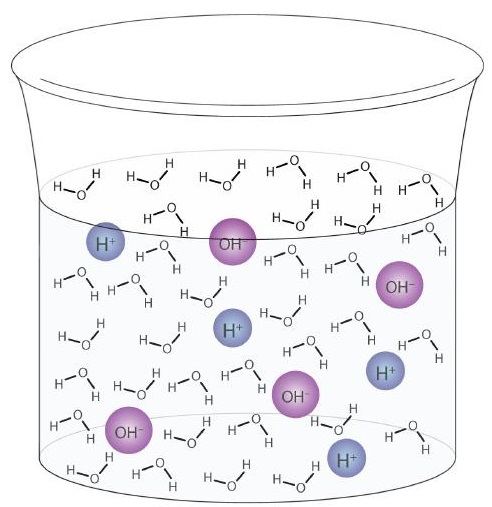

A water molecule can act as an acid or a base even in a sample of pure water. About 6 in every 100 million (6 in 108) water molecules undergo the following reaction:

\[H_2O_{(ℓ)} + H_2O_{(ℓ)} \rightarrow H_3O^+_{(aq)} + OH^−_{(aq)} \label{Eq3}\]

This process is called the autoionization of water (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)) and occurs in every sample of water, whether it is pure or part of a solution. Autoionization occurs to some extent in any amphiprotic liquid. (For comparison, liquid ammonia undergoes autoionization as well, but only about 1 molecule in a million billion (1 in 1015) reacts with another ammonia molecule.)

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Identify water as either a Brønsted-Lowry acid or a Brønsted-Lowry base.

- H2O(ℓ) + NO2−(aq) → HNO2(aq) + OH−(aq)

- HC2H3O2(aq) + H2O(ℓ) → H3O+(aq) + C2H3O2−(aq)

Solution

- In this reaction, the water molecule donates a proton to the NO2− ion, making OH−(aq). As the proton donor, H2O acts as a Brønsted-Lowry acid.

- In this reaction, the water molecule accepts a proton from HC2H3O2, becoming H3O+(aq). As the proton acceptor, H2O is a Brønsted-Lowry base.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Identify water as either a Brønsted-Lowry acid or a Brønsted-Lowry base.

- HCOOH(aq) + H2O(ℓ) → H3O+(aq) + HCOO−(aq)

- H2O(ℓ) + PO43−(aq) → OH−(aq) + HPO42−(aq)

Concept Review Exercises

- Explain how water can act as an acid.

- Explain how water can act as a base.

Answers

- Under the right conditions, H2O can donate a proton, making it a Brønsted-Lowry acid.

- Under the right conditions, H2O can accept a proton, making it a Brønsted-Lowry base.

Key Takeaway

- Water molecules can act as both an acid and a base, depending on the conditions.