5.8: Polyatomic Molecules- Water, Ammonia, and Methane

- Page ID

- 360450

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Determine the number of bonds formed by common nonmetal elements.

- Illustrate covalent bond formation with Lewis electron dot diagrams.

More than two atoms can participate in covalent bonding, although any given covalent bond will be between two atoms only. Water, ammonia, and methane are common examples that will be discussed in detail below. Carbon is unique in the extent to which it forms single, double, and triple bonds to itself and other elements. The number of bonds formed by an atom in its covalent compounds is not arbitrary. Hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon have very strong tendencies to form substances in which they have one, two, three, and four bonds to other atoms, respectively (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

| Atom | Number of Bonds |

|---|---|

| H (group 1) | 1 |

| O (group 16) | 2 |

| N (group 15) | 3 |

| C (group 14) | 4 |

Water

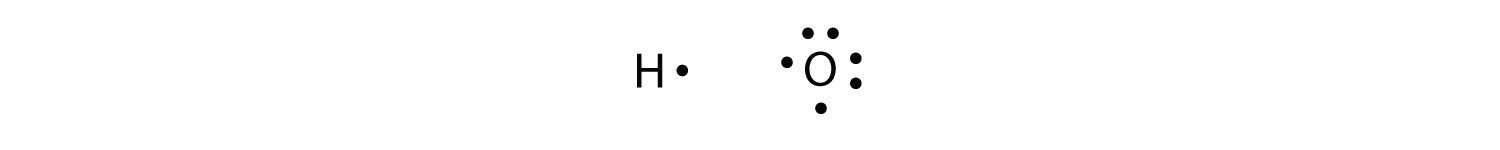

Consider H and O atoms:

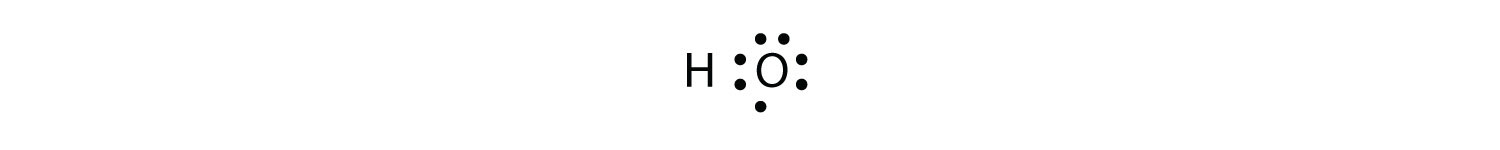

The H and O atoms can share an electron to form a covalent bond:

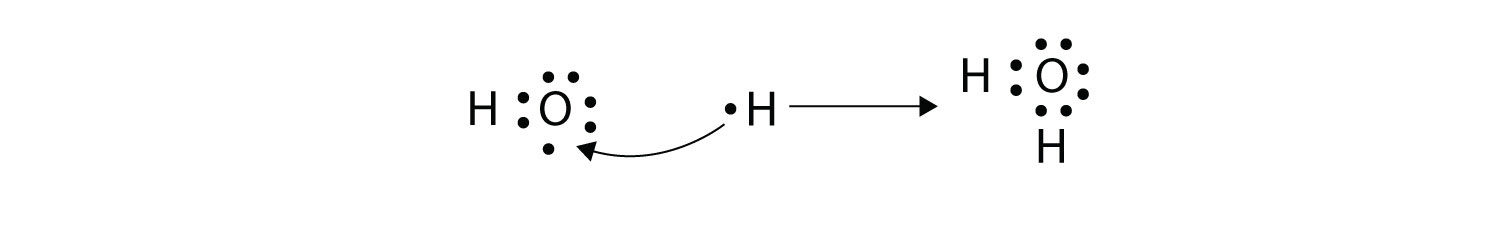

The H atom has a complete valence shell. However, the O atom has only seven electrons around it, which is not a complete octet. We fix this by including a second H atom, whose single electron will make a second covalent bond with the O atom:

(It does not matter on what side the second H atom is positioned.) Now the O atom has a complete octet around it, and each H atom has two electrons, filling its valence shell. This is how a water molecule, H2O, is made.

Ammonia

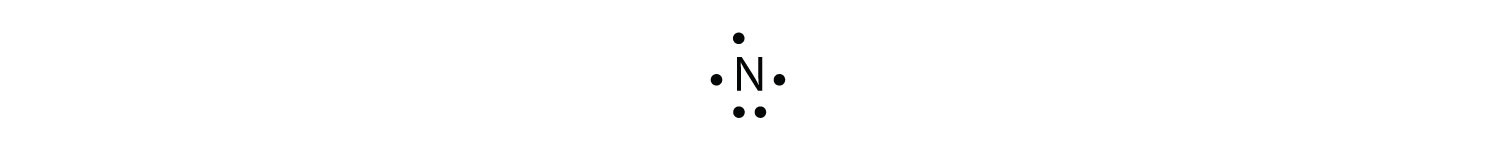

The N atom has the following Lewis electron dot diagram:

It has three unpaired electrons, each of which can make a covalent bond by sharing electrons with an H atom. The electron dot diagram of NH3 is as follows:

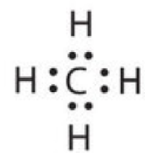

Methane

The C atom has the following Lewis electron dot diagram:

:C:

It has four unpaired electrons, each of which can make a covalent bond by sharing electrons with an H atom. The electron dot diagram of CH4 is as follows:

Writing Lewis Structures with the Octet Rule

For polyatomic molecules, it is helpful to follow the step-by-step procedure outlined here:

- Determine the total number of valence (outer shell) electrons among all the atoms.

- Draw a skeleton structure of the molecule, arranging the atoms around a central atom. (Generally, the element closest to the metals should be placed in the center. There are some exceptions) Connect each atom to the central atom with a single bond (one electron pair).

- Distribute the remaining electrons as lone pairs on the terminal atoms (except hydrogen), completing an octet around each atom.

- Place all remaining electrons on the central atom.

- Rearrange the electrons of the outer atoms to make multiple bonds with the central atom in order to obtain octets wherever possible.

1- Determine the total number of valence (outer shell) electrons in the molecule.

Since OF2 is a neutral molecule, we simply add the number of valence electrons:

OF2

O: 6 valence electrons/atom × 1 atom=6

+ F: 7 valence electrons/atom × 2 atoms=14

⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯

= 20 valence electrons

2- Draw a skeleton structure of the molecule, arranging the atoms around a central atom and connecting each atom to the central atom with a single (one electron pair) bond.

As the closest element to the metals, oxygen will be the central atom. After placing 2 single bonds (20 electrons - 4 electrons), we had 16 electrons remaining.

3- Distribute the remaining electrons as lone pairs on the terminal atoms (except hydrogen) to complete their valence shells with an octet of electrons.

4- For OF2, we placed 12 electrons between both Fluorine atoms, leaving 4 to be placed on the central atom:

5- Rearrange the electrons of the outer atoms to make multiple bonds with the central atom in order to obtain octets wherever possible.

In OF2, each atom has an octet as drawn, so nothing changes.

Summary

In polyatomic molecules, there is a pattern of covalent bonds that different atoms can form.

Contributors and Attributions

- TextMap: Beginning Chemistry (Ball et al.)