9.10: Gases in Chemical Reactions

- Page ID

- 381154

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

- To relate the amount of gas consumed or released in a chemical reaction to the stoichiometry of the reaction.

- To understand how the ideal gas equation and the stoichiometry of a reaction can be used to calculate the volume of gas produced or consumed in a reaction.

Introduction

With the ideal gas law, we can use the relationship between the amounts of gases (in moles) and their volumes (in liters) to calculate the stoichiometry of reactions involving gases, if the pressure and temperature are known. This is important for several reasons. Many reactions that are carried out in the laboratory involve the formation or reaction of a gas, so chemists must be able to quantitatively treat gaseous products and reactants as readily as they quantitatively treat solids or solutions. Furthermore, many, if not most, industrially important reactions are carried out in the gas phase for practical reasons. Gases mix readily, are easily heated or cooled, and can be transferred from one place to another in a manufacturing facility via simple pumps and plumbing. As a chemical engineer said to one of the authors, “Gases always go where you want them to, liquids sometimes do, but solids almost never do.”

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Sulfuric acid, the industrial chemical produced in greatest quantity (almost 45 million tons per year in the United States alone), is prepared by the combustion of sulfur in air to give SO2, followed by the reaction of SO2 with O2 in the presence of a catalyst to give SO3, which reacts with water to give H2SO4. The overall chemical equation is as follows:

\[\rm 2S_{(s)}+3O_{2(g)}+2H_2O_{(l)}\rightarrow 2H_2SO_{4(aq)}\]

What volume of O2 (in liters) at 22°C and 745 mmHg pressure is required to produce 1.00 ton (907.18 kg) of H2SO4?

Given: reaction, temperature, pressure, and mass of one product

Asked for: volume of gaseous reactant

Strategy:

A Calculate the number of moles of H2SO4 in 1.00 ton. From the stoichiometric coefficients in the balanced chemical equation, calculate the number of moles of O2 required.

B Use the ideal gas law to determine the volume of O2 required under the given conditions. Be sure that all quantities are expressed in the appropriate units.

Solution:

mass of H2SO4 → moles H2SO4 → moles O2 → liters O2A We begin by calculating the number of moles of H2SO4 in 1.00 ton:

\[\rm\dfrac{907.18\times10^3\;g\;H_2SO_4}{(2\times1.008+32.06+4\times16.00)\;g/mol}=9250\;mol\;H_2SO_4\]

We next calculate the number of moles of O2 required:

\[\rm9250\;mol\;H_2SO_4\times\dfrac{3mol\; O_2}{2mol\;H_2SO_4}=1.389\times10^4\;mol\;O_2\]

B After converting all quantities to the appropriate units, we can use the ideal gas law to calculate the volume of O2:

\[V=\dfrac{nRT}{P}=\rm\dfrac{1.389\times10^4\;mol\times0.08206\dfrac{L\cdot atm}{mol\cdot K}\times(273+22)\;K}{745\;mmHg\times\dfrac{1\;atm}{760\;mmHg}}=3.43\times10^5\;L\]

The answer means that more than 300,000 L of oxygen gas are needed to produce 1 ton of sulfuric acid. These numbers may give you some appreciation for the magnitude of the engineering and plumbing problems faced in industrial chemistry.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

In Example 5, we saw that Charles used a balloon containing approximately 31,150 L of H2 for his initial flight in 1783. The hydrogen gas was produced by the reaction of metallic iron with dilute hydrochloric acid according to the following balanced chemical equation:

\[Fe_{(s)} + 2 HCl_{(aq)} \rightarrow H_{2(g)} + FeCl_{2(aq)}\]

How much iron (in kilograms) was needed to produce this volume of H2 if the temperature was 30°C and the atmospheric pressure was 745 mmHg?

Answer: 68.6 kg of Fe (approximately 150 lb)

Ideal Gas law Equation and Reaction Stoichiometry: https://youtu.be/8pPlW8MRhgI

Reactions involving gases at STP

We can also use the fact that one mole of a gas occupies 22.414 L at STP in order to calculate the number of moles of a gas that is produced in a reaction. For example, the organic molecule ethane (CH3CH3) reacts with oxygen to give carbon dioxide and water according to the equation shown below:

2 CH3CH3 (g) + 7 O2 (g) → 4 CO2 (g) + 6 H2O (g)

An unknown mass of ethane is allowed to react with excess oxygen and the carbon dioxide produced is separated and collected. The carbon dioxide collected is found to occupy 11.23 L at STP; what mass of ethane was in the original sample?

Solution

Because the volume of carbon dioxide is measured at STP, the observed value can be converted directly into moles of carbon dioxide by dividing by 22.414 L mol–1. Once moles of carbon dioxide are known, the stoichiometry of the problem can be used to directly give moles of ethane (molar mass 30.07 g mol-1), which leads directly to the mass of ethane in the sample.

\[(11.23\; L\; CO_{2})\times \left ( \frac{1\; mol}{22.414\; L} \right )=0.501\; mol\; CO_{2}\]

Reaction stoichiometry:

\[(0.501\; mol\; CO_{2})\times \left ( \frac{2\; mol\; CH_{3}CH_{3}}{4\; mol\; CO_{2}} \right )=0.250\; mol\; CH_{3}CH_{3}\]

The ideal gas laws allow a quantitative analysis of whole spectrum of chemical reactions. When you are approaching these problems, remember to first decide on the class of the problem:

- If it is a non standard state problem (a gas is produced at a given set of conditions), then you want to use PV = nRT.

- If the volume of gas is quoted at STP, you can quickly convert this volume into moles by converting using the expression 22.4 L = 1 mol of gas at STP.

Once you have isolated your approach ideal gas law problems are no more complex that the stoichiometry problems we have addressed in earlier chapters.

- An automobile air bag requires about 62 L of nitrogen gas in order to inflate. The nitrogen gas is produced by the decomposition of sodium azide, according to the equation shown below

2 NaN3 (s) → 2 Na (s) + 3 N2 (g)

What mass of sodium azide is necessary to produce the required volume of nitrogen at 25 ˚C and 1 atm?

- Answer

-

110. g NaN3

- When Fe2O3 is heated in the presence of carbon, CO2 gas is produced, according to the equation shown below. A sample of 96.9 grams of Fe2O3 is heated in the presence of excess carbon and the CO2 produced is collected and measured at 1.00 atm and 273 K. What volume of CO2 will be observed?

2 Fe2O3(s) + 3 C (s) → 4 Fe (s) + 3 CO2 (g)

- Answer

-

20.4 L CO2

- The reaction of zinc and hydrochloric acid generates hydrogen gas, according to the equation shown below. An unknown quantity of zinc in a sample is observed

to produce 7.50 L of hydrogen gas at STP. How many grams of zinc were in the sample?

Zn (s) + 2 HCl (aq) → ZnCl2 (aq) + H2 (g)

- Answer

-

21.9 g Zn

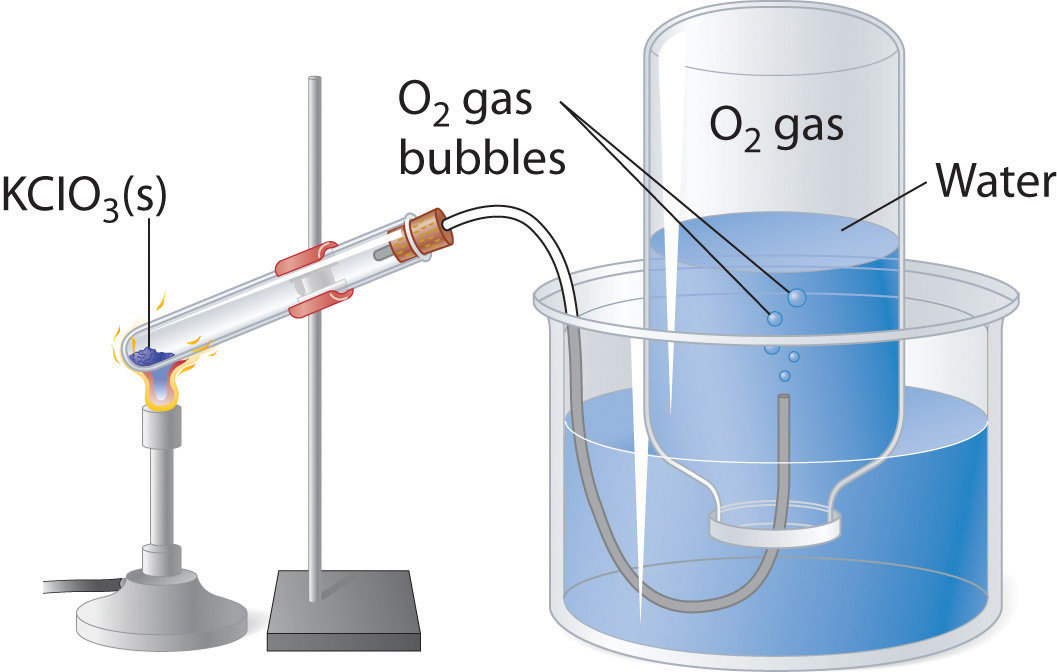

Collecting gases over water

As shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), a common laboratory method of collecting the gaseous product of a chemical reaction is to conduct it into an inverted tube or bottle filled with water, the opening of which is immersed in a larger container of water. Because the gas is less dense than liquid water, it bubbles to the top of the bottle, displacing the water. Eventually, all the water is forced out and the bottle contains only gas. If a calibrated bottle is used (i.e., one with markings to indicate the volume of the gas) and the bottle is raised or lowered until the level of the water is the same both inside and outside, then the pressure within the bottle will exactly equal the atmospheric pressure measured separately with a barometer (\(P_{\rm bar.}\)).

Remember, however, when calculating the amount of gas formed in the reaction, the gas collected inside the bottle is not pure. Instead, it is a mixture of the product gas and water vapor. All liquids (including water) have a measurable amount of vapor in equilibrium with the liquid because molecules of the liquid are continuously escaping from the liquid’s surface, while other molecules from the vapor phase collide with the surface and return to the liquid. The vapor thus exerts a pressure above the liquid, which is called the liquid’s vapor pressure. In the case shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), the bottle is therefore actually filled with a mixture of O2 and water vapor, and the total pressure is, by Dalton’s law of partial pressures, the sum of the pressures of the two components:

\[P_{\rm tot}=P_{\rm gas}+P_{\rm H_2O}=P_{\rm bar.} \label{6.6.1}\]

If we want to know the pressure of the gas generated in the reaction to calculate the amount of gas formed, we must first subtract the pressure due to water vapor from the total pressure. This is done by referring to tabulated values of the vapor pressure of water as a function of temperature (Table \(\PageIndex{1}\)).

| T (°C) | P (in mmHg) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 4.58 |

| 15 | 12.79 |

| 17 | 14.53 |

| 19 | 16.48 |

| 21 | 18.65 |

| 23 | 21.07 |

| 25 | 23.76 |

| 30 | 31.82 |

| 50 | 92.51 |

| 70 | 233.8 |

| 100 | 760.0 |

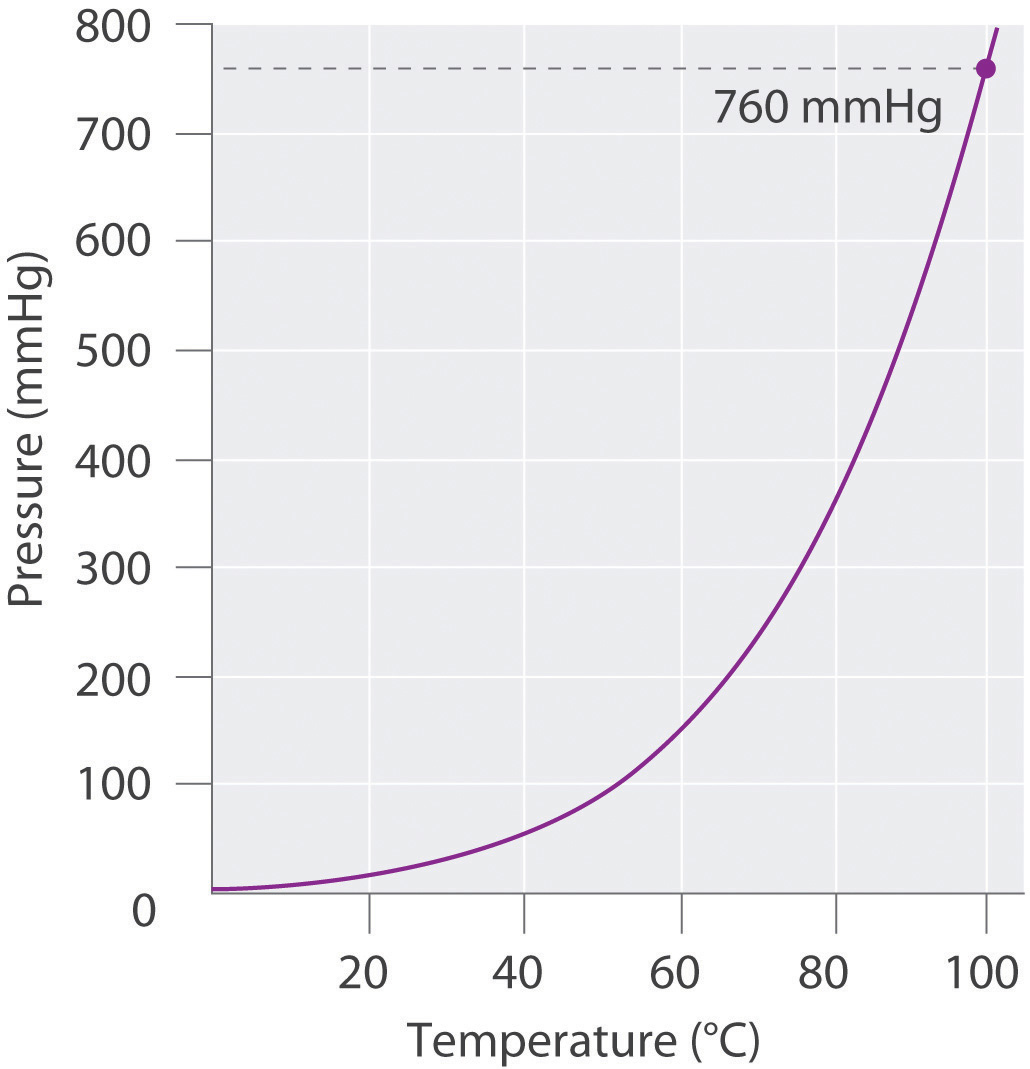

As shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), the vapor pressure of water increases rapidly with increasing temperature, and at the normal boiling point (100°C), the vapor pressure is exactly 1 atm. The methodology is illustrated in Example \(\PageIndex{2}\). The only gases that cannot be collected using this technique are those that readily dissolve in water (e.g., NH3, H2S, and CO2) and those that react rapidly with water (such as F2 and NO2).

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): A Plot of the Vapor Pressure of Water versus Temperature. The vapor pressure is very low (but not zero) at 0°C and reaches 1 atm = 760 mmHg at the normal boiling point, 100°C.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Sodium azide (\(NaN_3\)) decomposes to form sodium metal and nitrogen gas according to the following balanced chemical equation:

\[ 2NaN_3 \rightarrow 2Na_{(s)} + 3N_{2\; (g)}\]

This reaction is used to inflate the air bags that cushion passengers during automobile collisions. The reaction is initiated in air bags by an electrical impulse and results in the rapid evolution of gas. If the \(N_2\) gas that results from the decomposition of a 5.00 g sample of \(NaN_3\) could be collected by displacing water from an inverted flask, as in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\), what volume of gas would be produced at 21°C and 762 mmHg?

Given: reaction, mass of compound, temperature, and pressure

Asked for: volume of nitrogen gas produced

Strategy:

A Calculate the number of moles of N2 gas produced. From the data in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), determine the partial pressure of N2 gas in the flask.

B Use the ideal gas law to find the volume of N2 gas produced.

Solution:

A Because we know the mass of the reactant and the stoichiometry of the reaction, our first step is to calculate the number of moles of N2 gas produced:

\[\rm\dfrac{5.00\;g\;NaN_3}{(22.99+3\times14.01)\;g/mol}\times\dfrac{3mol\;N_2}{2mol\;NaN_3}=0.115\;mol\; N_2\]

The pressure given (762 mmHg) is the total pressure in the flask, which is the sum of the pressures due to the N2 gas and the water vapor present. Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) tells us that the vapor pressure of water is 18.65 mmHg at 21°C (294 K), so the partial pressure of the N2 gas in the flask is only

\[\rm(762 − 18.65)\;mmHg \times\dfrac{1\;atm}{760\;atm}= 743.4\; mmHg \times\dfrac{1\;atm}{760\;atm}= 0.978\; atm.\]

B Solving the ideal gas law for V and substituting the other quantities (in the appropriate units), we get

\[V=\dfrac{nRT}{P}=\rm\dfrac{0.115\;mol\times0.08206\dfrac{atm\cdot L}{mol\cdot K}\times294\;K}{0.978\;atm}=2.84\;L\]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

A 1.00 g sample of zinc metal is added to a solution of dilute hydrochloric acid. It dissolves to produce H2 gas according to the equation Zn(s) + 2 HCl(aq) → H2(g) + ZnCl2(aq). The resulting H2 gas is collected in a water-filled bottle at 30°C and an atmospheric pressure of 760 mmHg. What volume does it occupy?

Answer: 0.397 L

Collecting a Product Gas over Water: https://youtu.be/zFuy3t81vjQ

Summary

The relationship between the amounts of products and reactants in a chemical reaction can be expressed in units of moles or masses of pure substances, of volumes of solutions, or of volumes of gaseous substances. The ideal gas law can be used to calculate the volume of gaseous products or reactants as needed. In the laboratory, gases produced in a reaction are often collected by the displacement of water from filled vessels; the amount of gas can then be calculated from the volume of water displaced and the atmospheric pressure. A gas collected in such a way is not pure, however, but contains a significant amount of water vapor. The measured pressure must therefore be corrected for the vapor pressure of water, which depends strongly on the temperature.