6.1: Prelude to Energy Metabolism

- Page ID

- 178799

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The discovery of the link between insulin and diabetes led to a period of intense research aimed at understanding exactly how insulin works in the body to regulate glucose levels. Hormones in general act by binding to some protein, known as the hormone’s receptor, thus initiating a series of events that lead to a desired outcome. In the early 1970s, the insulin receptor was purified, and researchers began to study what happens after insulin binds to its receptor and how those events are linked to the uptake and metabolism of glucose in cells.

The insulin receptor is located in the cell membrane and consists of four polypeptide chains: two identical chains called α chains and two identical chains called β chains. The α chains, positioned on the outer surface of the membrane, consist of 735 amino acids each and contain the binding site for insulin. The β chains are integral membrane proteins, each composed of 620 amino acids. The binding of insulin to its receptor stimulates the β chains to catalyze the addition of phosphate groups to the specific side chains of tyrosine (referred to as phosphorylation) in the β chains and other cell proteins, leading to the activation of reactions that metabolize glucose. In this chapter we will look at the pathway that breaks down glucose—in response to activation by insulin—for the purpose of providing energy for the cell.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Model of the Structure of the Insulin Receptor (PDB code 4ZXB).

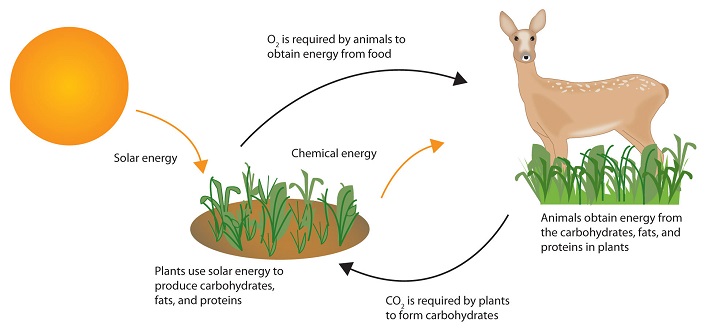

Life requires energy. Animals, for example, require heat energy to maintain body temperature, mechanical energy to move their limbs, and chemical energy to synthesize the compounds needed by their cells. Living cells remain organized and functioning properly only through a continual supply of energy. But only specific forms of energy can be used. Supplying a plant with energy by holding it in a flame will not prolong its life. On the other hand, a green plant is able to absorb radiant energy from the sun, the most abundant source of energy for life on the earth. Plants use this energy first to form glucose and then to make other carbohydrates, as well as lipids and proteins. Unlike plants, animals cannot directly use the sun’s energy to synthesize new compounds. They must eat plants or other animals to get carbohydrates, fats, and proteins and the chemical energy stored in them. Once digested and transported to the cells, the nutrient molecules can be used in either of two ways: as building blocks for making new cell parts or repairing old ones or “burned” for energy.

The thousands of coordinated chemical reactions that keep cells alive are referred to collectively as metabolism. In general, metabolic reactions are divided into two classes: the breaking down of molecules to obtain energy is catabolism, and the building of new molecules needed by living systems is anabolism.

metabolite

Any chemical compound that participates in a metabolic reaction is a metabolite.

Most of the energy required by animals is generated from lipids and carbohydrates. These fuels must be oxidized, or “burned,” for the energy to be released. The oxidation process ultimately converts the lipid or carbohydrate to carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O).

Carbohydrate:

\[\ce{C6H12O6 + 6O2 → 6CO2 + 6H2O + 670 kcal}\]

Lipid:

\[\ce{C16H32O2 + 23O2 → 16CO2 + 16H2O + 2,385 kcal}\]

These two equations summarize the biological combustion of a carbohydrate and a lipid by the cell through respiration. Respiration is the collective name for all metabolic processes in which gaseous oxygen is used to oxidize organic matter to carbon dioxide, water, and energy.

Like the combustion of the common fuels we burn in our homes and cars (wood, coal, gasoline), respiration uses oxygen from the air to break down complex organic substances to carbon dioxide and water. But the energy released in the burning of wood is manifested entirely in the form of heat, and excess heat energy is not only useless but also injurious to the living cell. Living organisms instead conserve much of the energy respiration releases by channeling it into a series of stepwise reactions that produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or other compounds that ultimately lead to the synthesis of ATP. The remainder of the energy is released as heat and manifested as body temperature.