11.9: Addition of Water

- Page ID

- 30481

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Reaction: Hydration of Alkynes

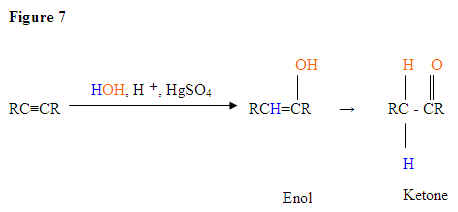

As with alkenes,hydration (addition of water) to alkynes requires a strong acid, usually sulfuric acid, and is facilitated by mercuric sulfate. However, unlike the additions to double bonds which give alcohol products, addition of water to alkynes gives ketone products ( except for acetylene which yields acetaldehyde ). The explanation for this deviation lies in enol-keto tautomerization, illustrated by the following equation. The initial product from the addition of water to an alkyne is an enol (a compound having a hydroxyl substituent attached to a double-bond), and this immediately rearranges to the more stable keto tautomer.

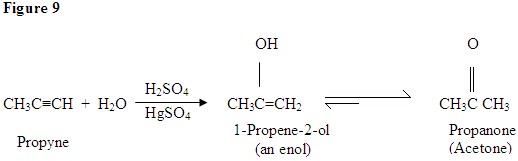

Tautomers are defined as rapidly interconverted constitutional isomers, usually distinguished by a different bonding location for a labile hydrogen atom (colored red here) and a differently located double bond. The equilibrium between tautomers is not only rapid under normal conditions, but it often strongly favors one of the isomers ( acetone, for example, is 99.999% keto tautomer ). Even in such one-sided equilibria, evidence for the presence of the minor tautomer comes from the chemical behavior of the compound. Tautomeric equilibria are catalyzed by traces of acids or bases that are generally present in most chemical samples. The three examples shown below illustrate these reactions for different substitutions of the triple-bond. The tautomerization step is indicated by a red arrow. For terminal alkynes the addition of water follows the Markovnikov rule, as in the second example below, and the final product ia a methyl ketone ( except for acetylene, shown in the first example ). For internal alkynes ( the triple-bond is within a longer chain ) the addition of water is not regioselective. If the triple-bond is not symmetrically located ( i.e. if R & R' in the third equation are not the same ) two isomeric ketones will be formed.

| HC≡CH + H2O + HgSO4 & H2SO4 ——> [ H2C=CHOH ] ——> H3C-CH=O |

| RC≡CH + H2O + HgSO4 & H2SO4 ——> [ RC(OH)=CH2 ] ——> RC(=O)CH3 |

| RC≡CR' + H2O + HgSO4 & H2SO4 ——> [ RHC=C(OH)R' + RC(OH)=CHR' ] ——> RCH2-C(=O)R' + RC(=O)-CH2R' |

With the addition of water, alkynes can be hydrated to form enols that spontaneously tautomerize to ketones. Reaction is catalyzed by mercury ions. Follows Markovnikov’s Rule: Terminal alkynes give methyl ketones

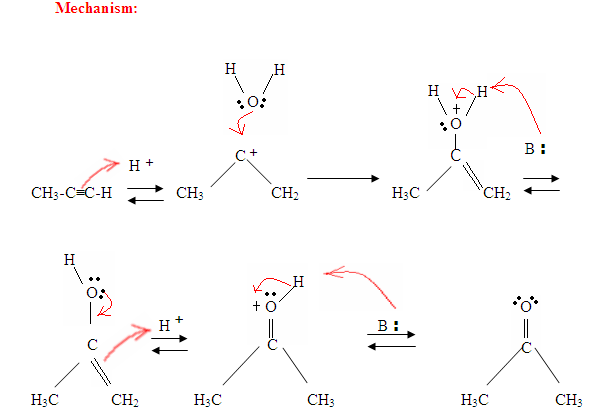

- The first step is an acid/base reaction where the

π electrons of the triple bond acts as a Lewis base and attacks the proton therefore protinating the carbon with the most hydrogen substituents. - The second step is the attack of the nucleophilic water molecule on the electrophilic carbocation, which creates an oxonium ion.

- Next you deprotonate by a base, generating an alcohol called an enol, which then tautomerizes into a ketone.

- Tautomerism is a simultaneous proton and double bond shift, which goes from the enol form to the keto isomer form as shown above in Figure 7.

Now let's look at some Hydration Reactions.

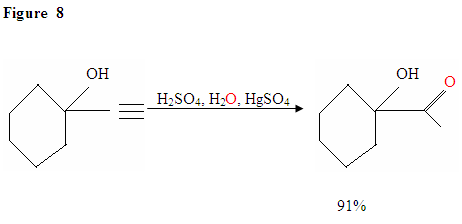

Hydration of Terminal Alkyne produces methyl ketones

Just as described in Figure 7 the

Hydration of Alkyne

As you can see here, the

Tautomerism is shown here when the proton gets attacked by the double bond

Contributors

William Reusch, Professor Emeritus (Michigan State U.), Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry

- Prof. Hilton Weiss (Bard College)

- Aleksandra Milman