1.7: Polarity of Molecules

- Page ID

- 30254

Dipole moments occur when there is a separation of charge. They can occur between two ions in an ionic bond or between atoms in a covalent bond; dipole moments arise from differences in electronegativity. The larger the difference in electronegativity, the larger the dipole moment. The distance between the charge separation is also a deciding factor into the size of the dipole moment. The dipole moment is a measure of the polarity of the molecule.

Introduction

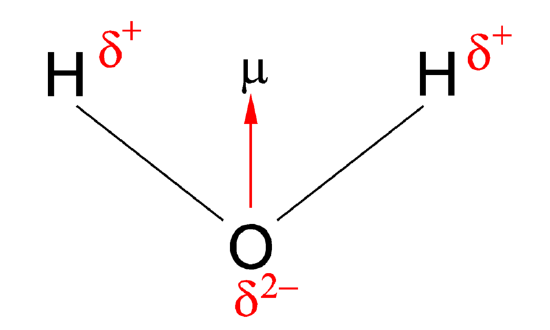

When atoms in a molecule share electrons unequally, they create what is called a dipole moment. This occurs when one atom is more electronegative than another, resulting in that atom pulling more tightly on the shared pair of electrons, or when one atom has a lone pair of electrons and the difference of electronegativity vector points in the same way. One of the most common examples is the water molecule, made up of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms. The differences in electronegativity and lone electrons give oxygen a partial negative charge and each hydrogen a partial positive charge.

Dipole Moment

When two electrical charges, of opposite sign and equal magnitude, are separated by a distance, a dipole is established. The size of a dipole is measured by its dipole moment ((\mu\)). Dipole moment is measured in debye units, which is equal to the distance between the charges multiplied by the charge (1 debye equals 3.34 x 10-30 coulomb-meters). The equation to figure out the dipole moment of a molecule is given below:

where

μ is the dipole moment,q is the magnitude of the charge, andr is the distance between the charges.

The dipole moment acts in the direction of the vector quantity. An example of a polar molecule is

Figure 1: Dipole moment of water

The vector points from positive to negative, on both the molecular (net) dipole moment and the individual bond dipoles. The table above shows the electronegativity of some of the common elements. The larger the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms, the more electronegative that bond is. To be considered a polar bond, the difference in electronegativity must be large. The dipole moment points in the direction of the vector quantity of each of the bond electronegativities added together.

| Example 1: Water |

|---|

| The water molecule picture from Figure 1 can be used to determine the direction and magnitude of the dipole moment. From the electronegativities of water and hydrogen, the difference is 1.2 for each of the hydrogen-oxygen bonds. Next, because the oxygen is the more electronegative atom, it exerts a greater pull on the shared electrons; it also has two lone pairs of electrons. From this, it can be concluded that the dipole moment points from between the two hydrogen atoms toward the oxygen atom. Using the equation above, the dipole moment is calculated to be 1.85 D by multiplying the distance between the oxygen and hydrogen atoms by the charge difference between them and then finding the components of each that point in the direction of the net dipole moment (remember the angle of the molecule is 104.5˚). The bond moment of O-H bond =1.5 D, so the net dipole moment =2(1.5)×cos(104.5/2)=1.84 D. |

Dipole Moments

It is relatively easy to measure dipole moments. Place substance between charged plates--polar molecules increase the charge stored on plates and the dipole moment can be obtained (has to do with capacitance). Polar molecules align themselves:

- in an electric field

- with respect to one another

- with respect to ions

Nonpolar

Figure 2: Polar molecules align themselves in an electric field (left), with respect to one another (middle), and with respect to ions (right)

When proton & electron close together, the dipole moment (degree of polarity) decreases. However, as proton & electron get farther apart, the dipole moment increases. In this case, the dipole moment calculated as:

The debye characterizes size of dipole moment. When a proton & electron 100 pm apart, the dipole moment is

- When proton & electron are separated by 120 pm,

- When proton & electron are separated by 150 pm,

- When proton & electron are separated by 200 pm,

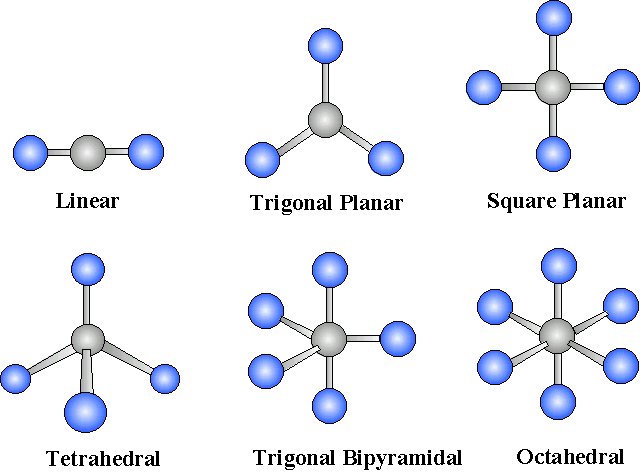

Polarity and Structure of Molecules

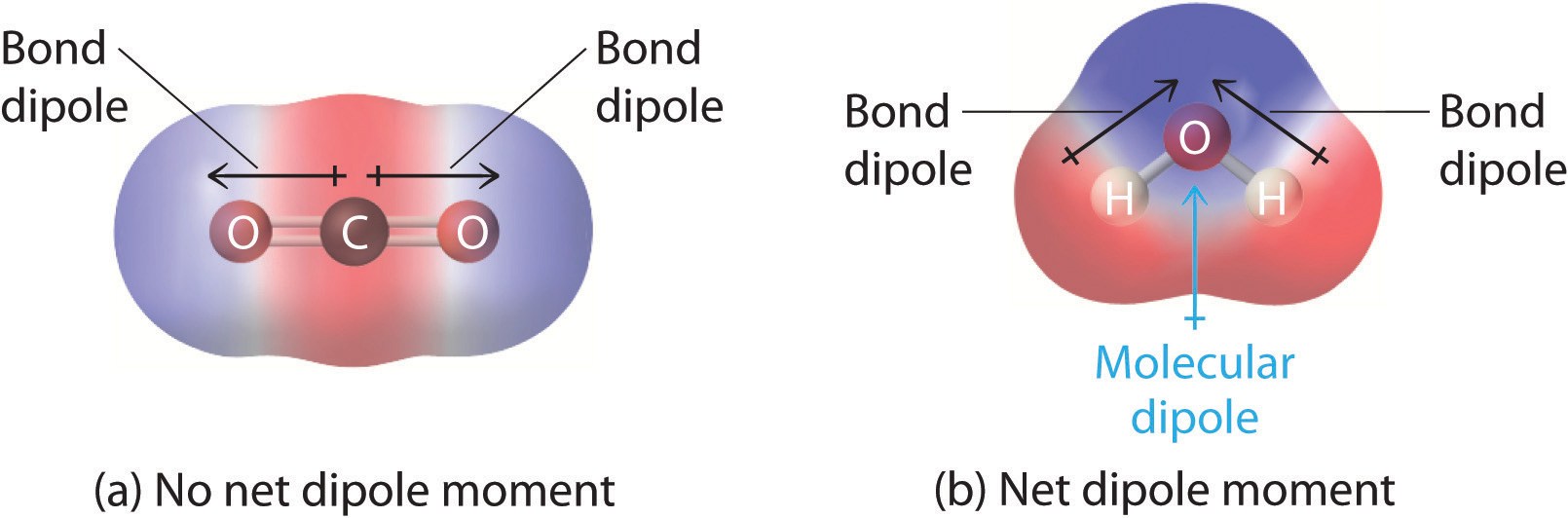

The shape of a molecule and the polarity of its bonds determine the OVERALL POLARITY of that molecule. A molecule that contains polar bonds, might not have any overall polarity, depending upon its shape. The simple definition of whether a complex molecule is polar or not depends upon whether its overall centers of positive and negative charges overlap. If these centers lie at the same point in space, then the molecule has no overall polarity (and is non polar).

Figure 3: Charge distrubtions

If a molecule is completely symmetric, then the dipole moment vectors on each molecule will cancel each other out, making the molecule nonpolar. A molecule can only be polar if the structure of that molecule is not symmetric.

A good example of a nonpolar molecule that contains polar bonds is carbon dioxide. This is a linear molecule and the C=O bonds are, in fact, polar. The central carbon will have a net positive charge, and the two outer oxygens a net negative charge. However, since the molecule is linear, these two bond dipoles cancel each other out (i.e. vector addition of the dipoles equals zero). And the overall molecule has no dipole (

Although a polar bond is a prerequisite for a molecule to have a dipole, not all molecules with polar bonds exhibit dipoles

Geometric Considerations

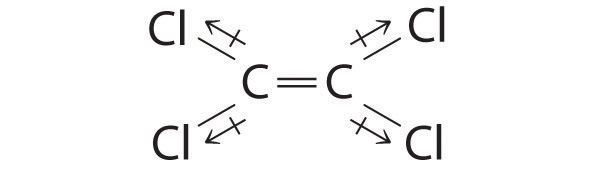

For

Figure 4: Molecular geometries with exact cancelation of polar bonding to generate a non-polar molecule (

| Example 2: |

|---|

| Although the C–Cl bonds are rather polar, the individual bond dipoles cancel one another in this symmetrical structure, and Cl2C=CCl2 does not have a net dipole moment.

|

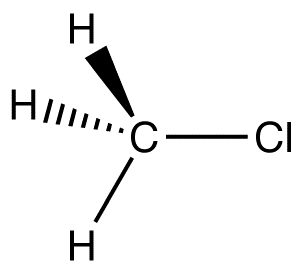

| Example 3: |

|---|

| C-Cl, the key polar bond, is 178 pm. Measurement reveals 1.87 D. From this data, % ionic character can be computed. If this bond were 100% ionic (based on proton & electron),

|

| Example 4: |

|---|

| Since measurement 1.87 D, % ionic = (1.7/8.54)x100 = 22% u = 1.03 D (measured) H-Cl bond length 127 pm If 100% ionic,

ionic = (1.03/6.09)x100 = 17% |

| Compound | Bond Length (Å) | Electronegativity Difference | Dipole Moment (D) |

| HF | 0.92 | 1.9 | 1.82 |

| HCl | 1.27 | 0.9 | 1.08 |

| HBr | 1.41 | 0.7 | 0.82 |

| HI | 1.61 | 0.4 | 0.44 |

Although the bond length is increasing, the dipole is decreasing as you move down the halogen group. The electronegativity decreases as we move down the group. Thus, the greater influence is the electronegativity of the two atoms (which influences the charge at the ends of the dipole).