12.19: Solutions to Selected Problems

- Page ID

- 140097

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)ProblemMO2.1.

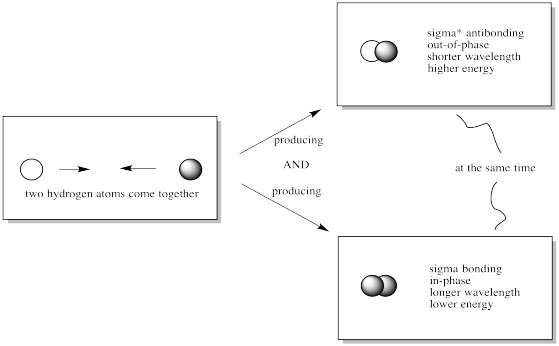

When two s orbitals combine out-of-phase, destructive intereference occurs.

There is a node between the atoms.

The energy of the electrons increases.

When two s orbitals combine in-phase, constructive interference occurs.

There is no node between the atoms; the electrons are found between the atoms.

The energy of the electrons decreases.

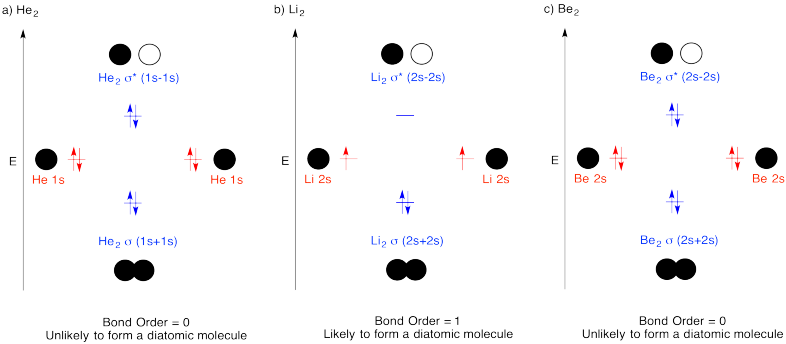

Problem MO3.1.

Problem MO4.1.

Problem MO4.2.

Problem MO5.1.

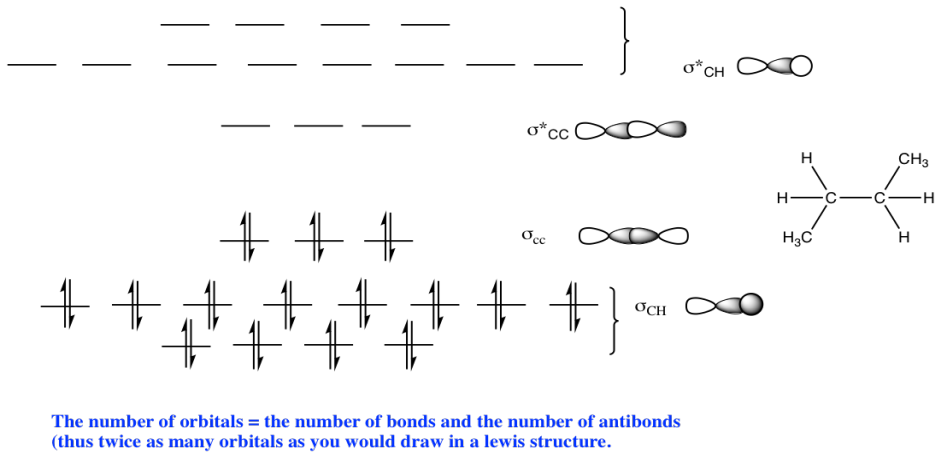

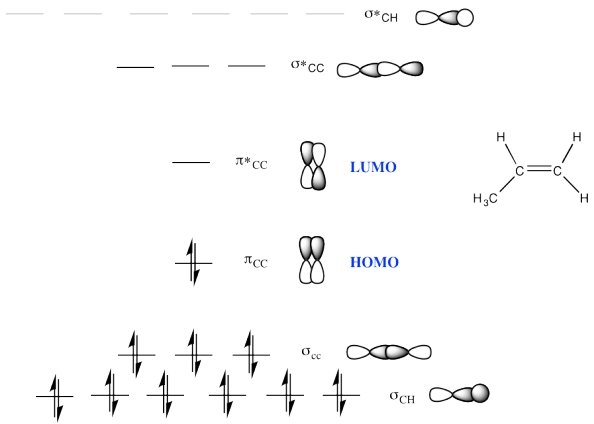

When 2 atomic orbitals are combined, 2 molecular orbitals are formed: one in-phase bonding orbital and one out-of-phase antibonding orbital.

Problem MO5.2.

In-phase combinations of atomic orbitals give bonding orbitals.

Problem MO5.3.

Out-of-phase combinations of atomic orbitals give antibonding orbitals.

Problem MO5.4.

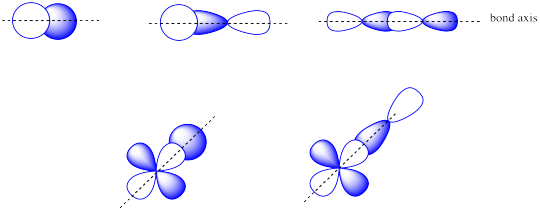

The combinations of s + s OR s + p OR p + p OR s + d OR p + d atomic orbitals can lead to σ orbitals.

Problem MO5.5.

The combinations of side by side p + p or p + d atomic orbitals leads to π orbitals.

Problem MO5.5.

e) σ*

Problem MO5.7.

Li+ and O2- are more similar in size than K+ and O2-, so the bond between Li+ and O2- is stronger.

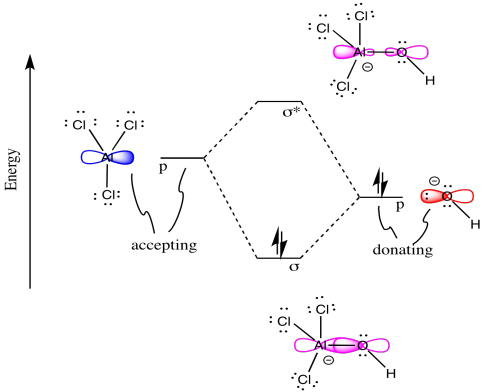

The energy difference between the 1s orbitals and 2s orbitals is too large, so they cannot interact. In order for orbitals to interact, the orbitals need to have the same symmetry, be in the same plane, and be similar in energy.

Problem MO5.8.

When two parallel p orbitals combine out-of-phase, destructive intereference occurs.

There is a node between the atoms.

The energy of the electrons increases.

When two parallel p orbitals combine in-phase, constructive interference occurs.

There is no node between the atoms; the electrons are found above and below the axis connecting the atoms.

The energy of the electrons decreases.

Problem MO6.1.

Problem MO6.2.

- Count the valence electrons on the molecule. That's the number of valence electrons on each atom, adjusted for any charge on the molecule. (eg C22- has 10 valence electrons: 4 from each carbon -- that's 8 -- and two more for the 2- charge).

- Fill electrons into the lowest energy orbitals first.

- Pair electrons after all orbitals at the same energy level have one electron.

Problem MO6.3.

Problem MO6.4.

Problem MO6.5.

Problem MO6.6.

Problem MO6.7.

Problem MO6.8.

Problem MO6.9.

Problem MO6.10

a) Na, because Na has a lower ionization potential (and a lower electronegativity) than Al.

b) Al

c) 4-, because there are four Na+

d) total e- = 2 x 3 e- (per Al) + 4 e- (for the negative charge) = 10 e-

e) ![]()

f)

g) bond order = (# bonding e- - # antibonding e-) / 2 = (8-2)/2 = 3

Problem MO7.1

From MO6: 3. Diamagnetic (no unpaired electrons); 4. Paramagnetic; 5. Diamagnetic; 6. Diamagnetic; 7. Paramagnetic; 8. Diamagnetic

Problem MO7.2

a. N2+. From the MO diagrams, N2+ has one less bonding electron. Thus, the bond order will be lower and the bond will be longer than in N2.

b. N2-. From the MO diagrams, N2- has one more antibonding electron. Thus the bond order will be lower and the bond will be longer than N2.

Problem MO7.3

a. O2+ . From the MO diagram, O2+ has one less antibonding electron. Thus the bond order will be higher and the bond will be stronger than in O2.

b. O2. From the MO diagram, O2 has one less antibonding electron. Thus the bond order will be higher and the bond will be stronger than in O2-.

Problem MO9.1

a)

b)

c)

Problem MO11.1.

a)

b)

c)

Problem MO11.2.

a)

b)

c)

d)

e)

Problem MO11.3.

Problem MO11.4.

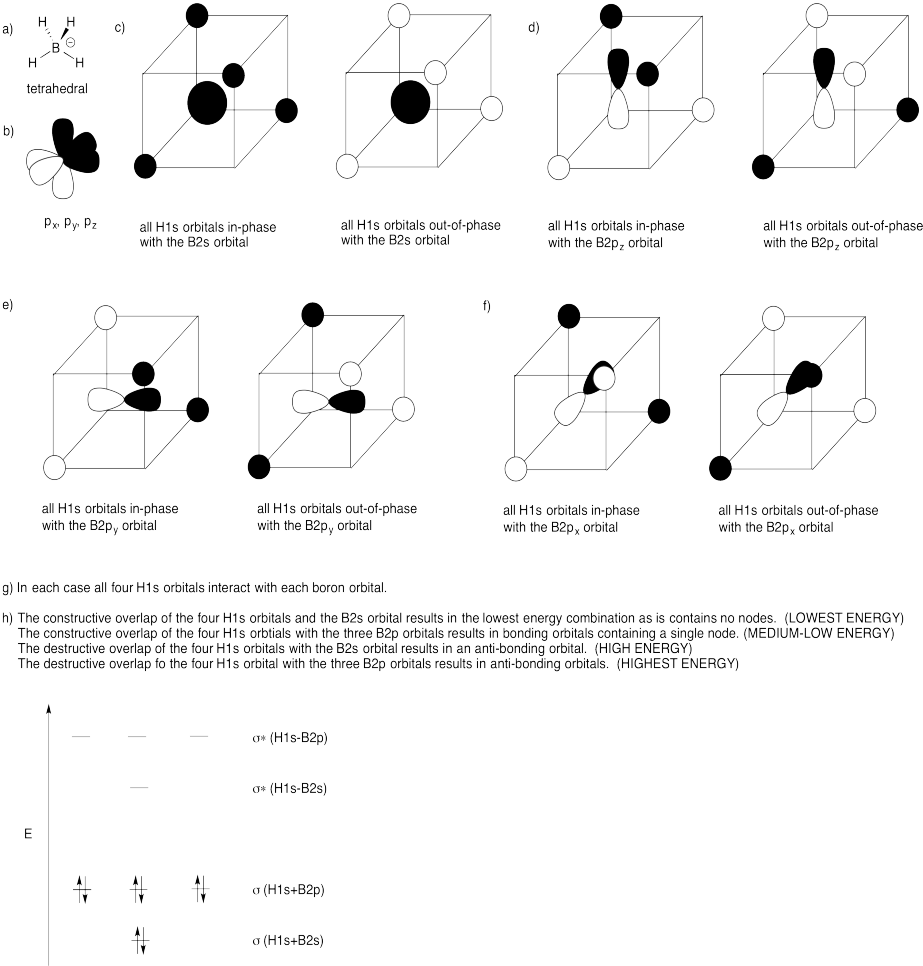

Problem MO12.1. & 12.2.

Problem MO12.3.

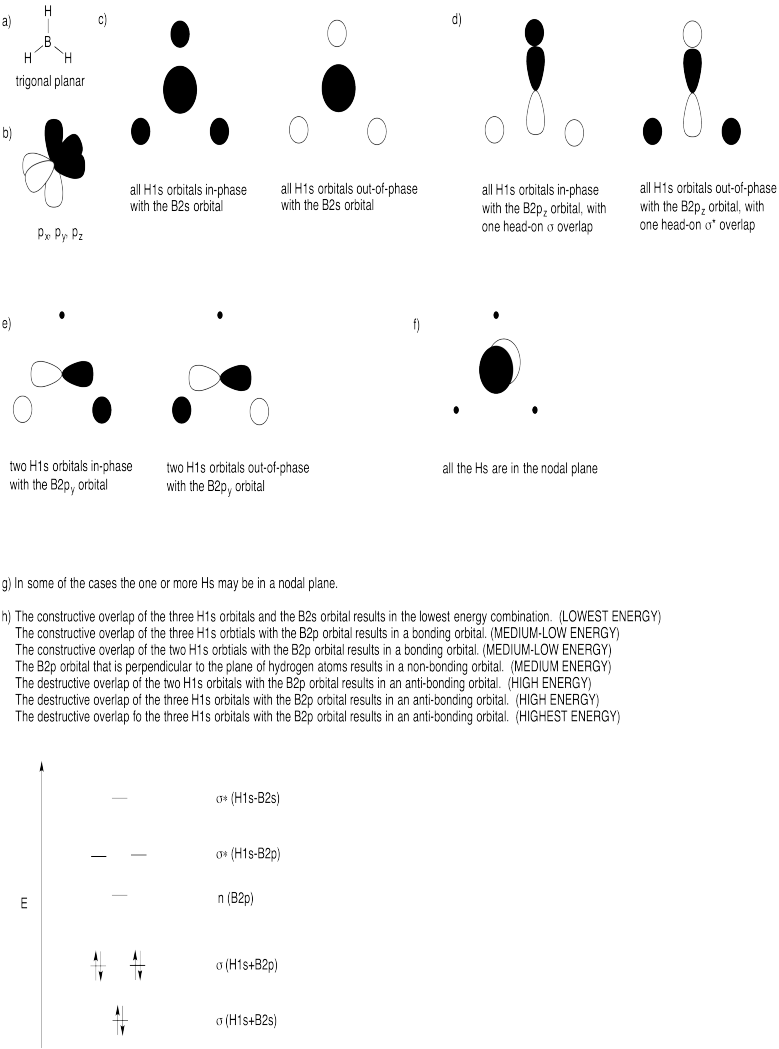

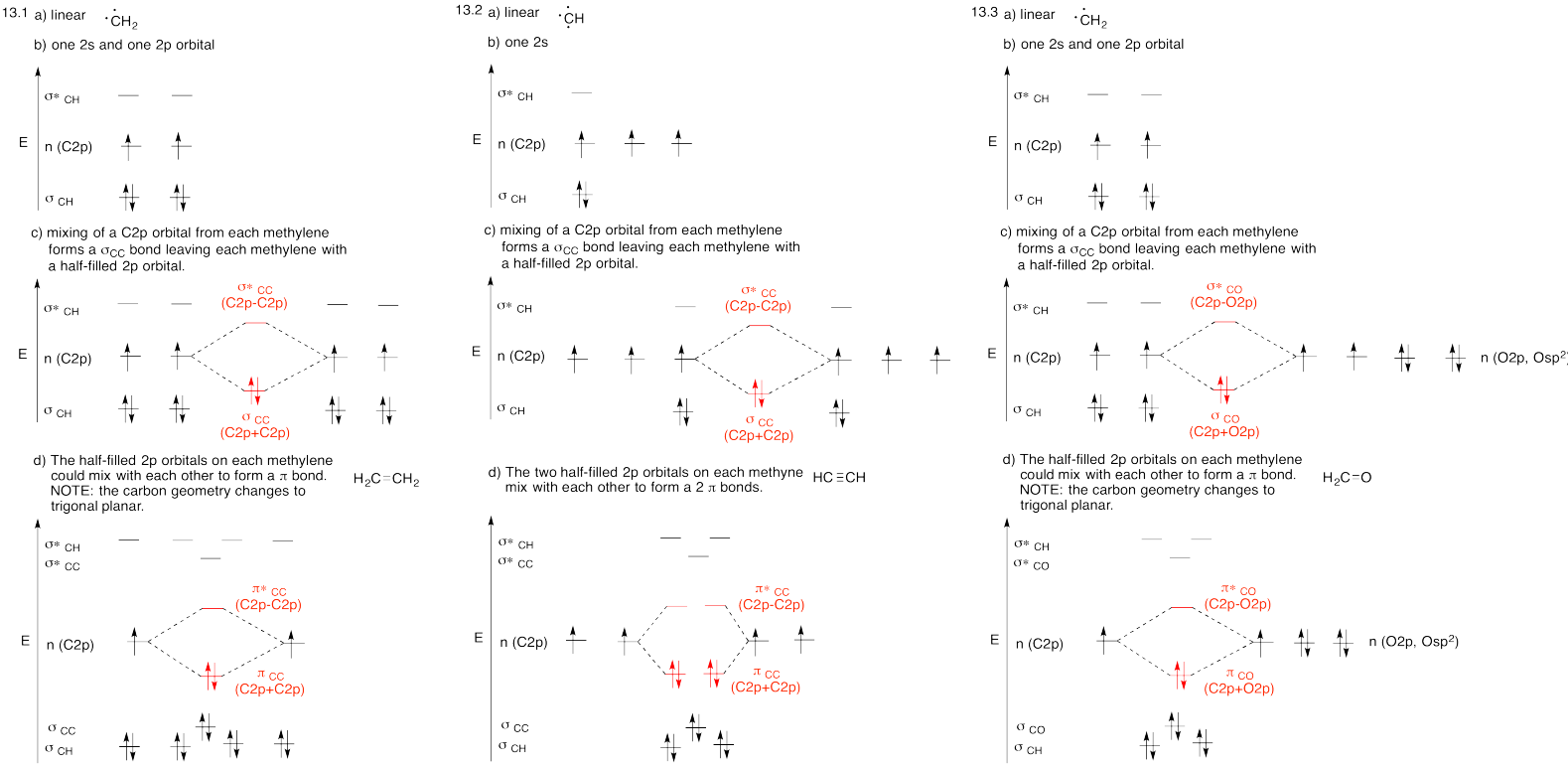

Problem MO13.1.-13.3.

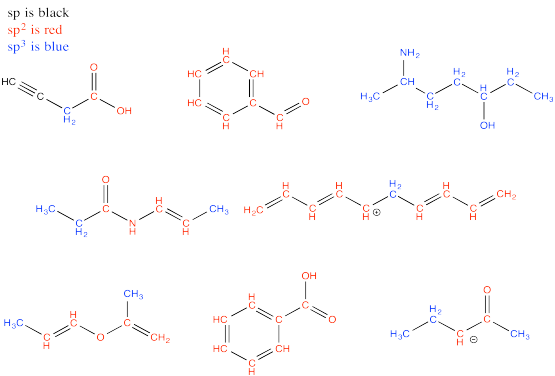

Problem MO14.1.-14.5.

Problem MO14.6.

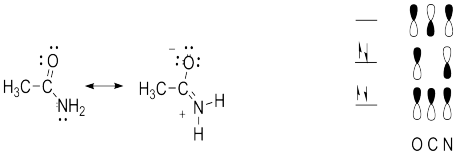

All of the answers depend on an understanding of the contributions of two resonance structures to the overall picture of acetaminde, or alternatively, that actetamide forms a conjugated pi system with four electrons delocalized over the O, C and N.

a. Contribution of the second resonance structure introduces some double bond character to the C-N bond and some single bond character to the C-O bond. Thus, both of these bonds are intermediate in length between single and double bonds.

b. Since the C, N and O atoms are sp2 hybridized, the C-N pi bond can only form if the remaining p orbitals on these atoms align. This places the atoms participating in the sp2 sigma bonds in the same plane.

c. Because of the partial double bond character there is a larger barrier to rotation than is typically found in molecules with only single bonds.

d. Because of the partial double bond character and the restricted rotation, the two H’s are not identical. (One is nearer the O and one is nearer the CH3 and the restricted rotation prevents their interconversion.

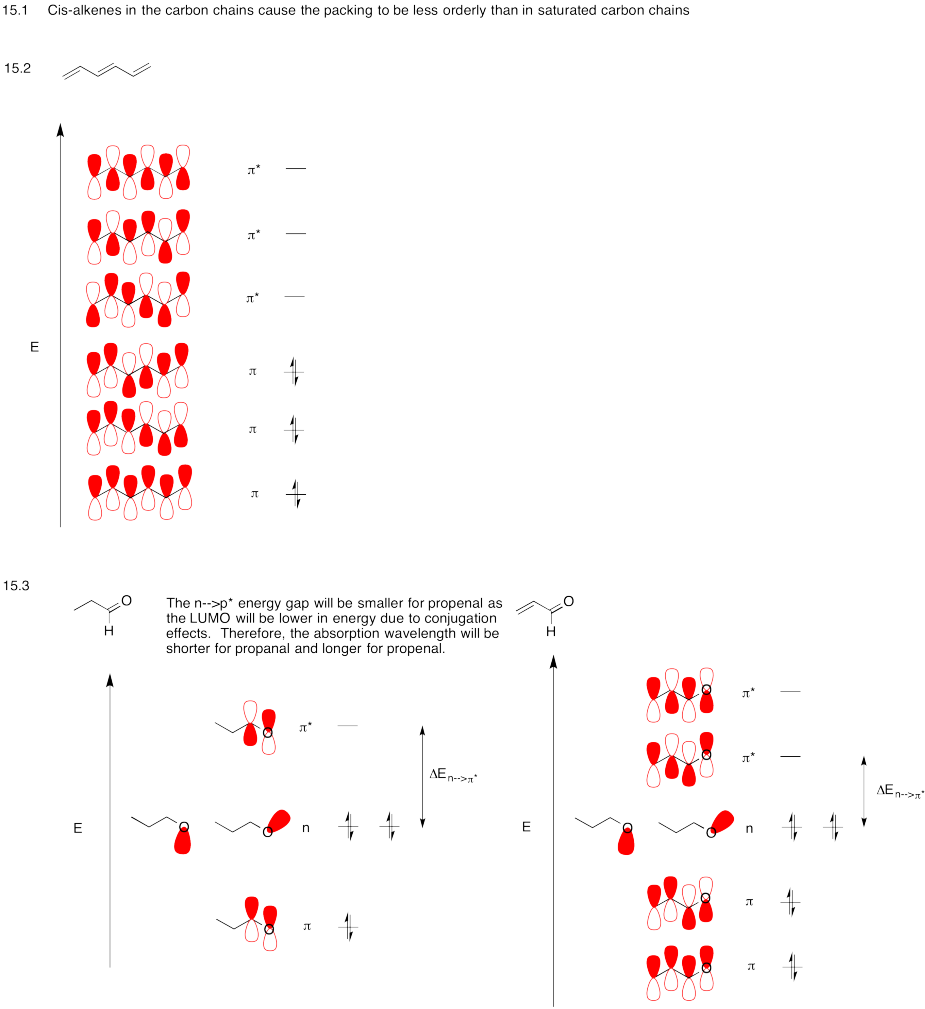

Problem MO15.1.-15.3.

Problem MO15.4.

Problem 16.1.

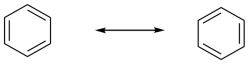

Because the two resonance structures shows double bonds in two different places, the implication is that all of the bonds in benzene have some double bond and some single bond character. You can think of them all as being about 1.5 bonds.

Problem 16.2.

a) non-aromatic b) non-aromatic c) aromatic d) aromatic e) anti-aromatic f) anti-aromatic

Problem 16.3.

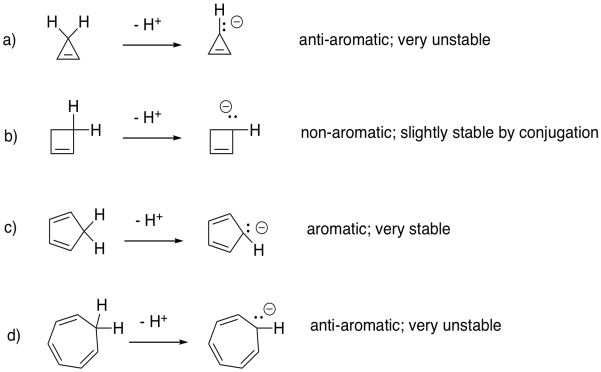

a) aromatic b) non-aromatic c) anti-aromatic d) aromatic

Problem 16.4.

a) aromatic b) anti-aromatic c) aromatic d) anti-aromatic

Problem 16.5.

Problem MO16.6.

Problem MO16.7.

In tropone, the resonance structure on the right shows more aromatic character, because it clearly shows a fully-conjugated ring with an odd number of electron pairs in the pi system. The carbonyl in the picture on the left makes that conjugation less obvious: does its carbonyl pi bond contribute to the conjugated system of the ring? If it does, that would mean four pairs of electrons in the pi system, and that would be an even number, so it would be anti-aromatic.

The hydroxy group in hydroxytropolone would stabilize the compound in the structure shown on the right, via an ion-dipole interaction with the anionic oxygen. That makes the right-hand, explicitly aromatic structure the dominant one.

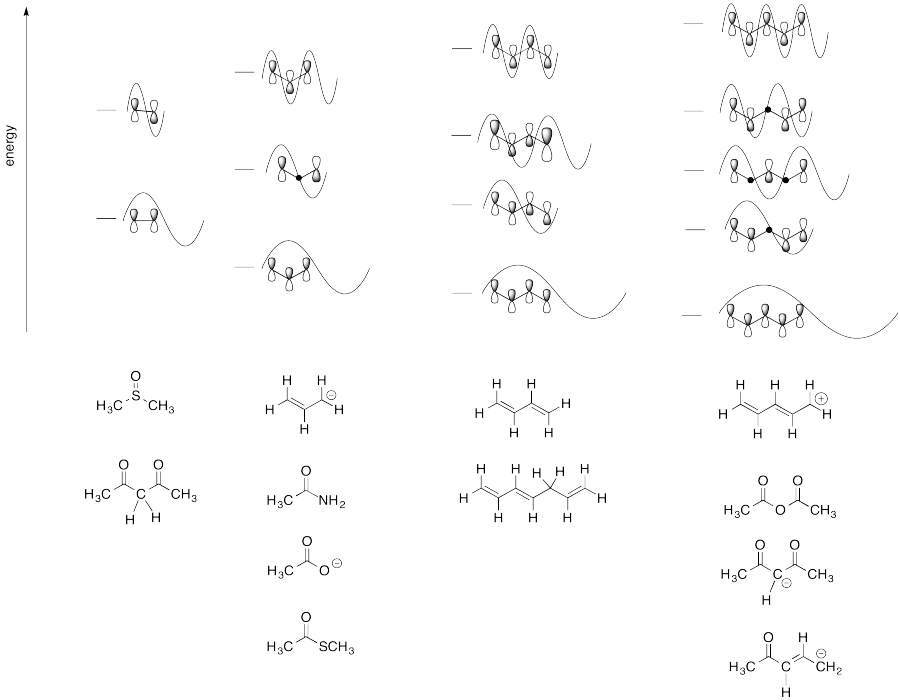

Problem MO17.1.

All of the compounds are aromatic and have the same Hückel MO diagram.

Problem MO17.2.

All of the compounds are aromatic and have the same Hückel MO diagram.