7.7: Buffers and Conjugate Acid-Base Pairs

- Page ID

- 483441

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Identify conjugate acid base pair.

- Define buffers and know the composition of different buffer systems.

- Describe how buffers work.

Conjugate Acid-Base Pair

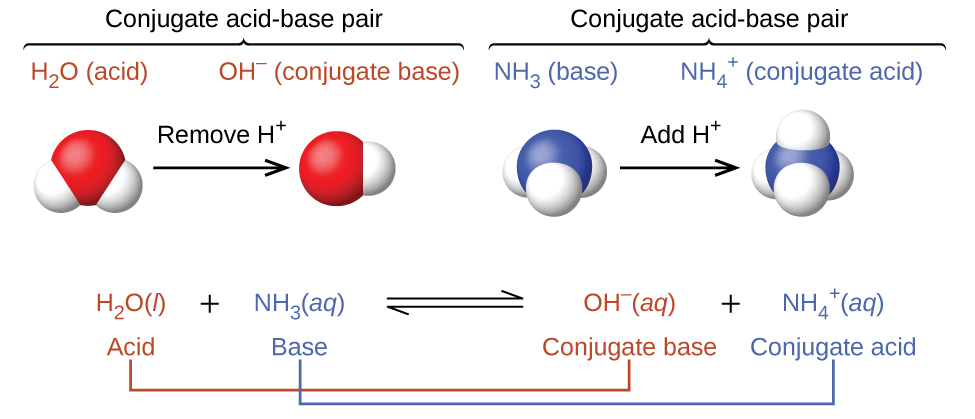

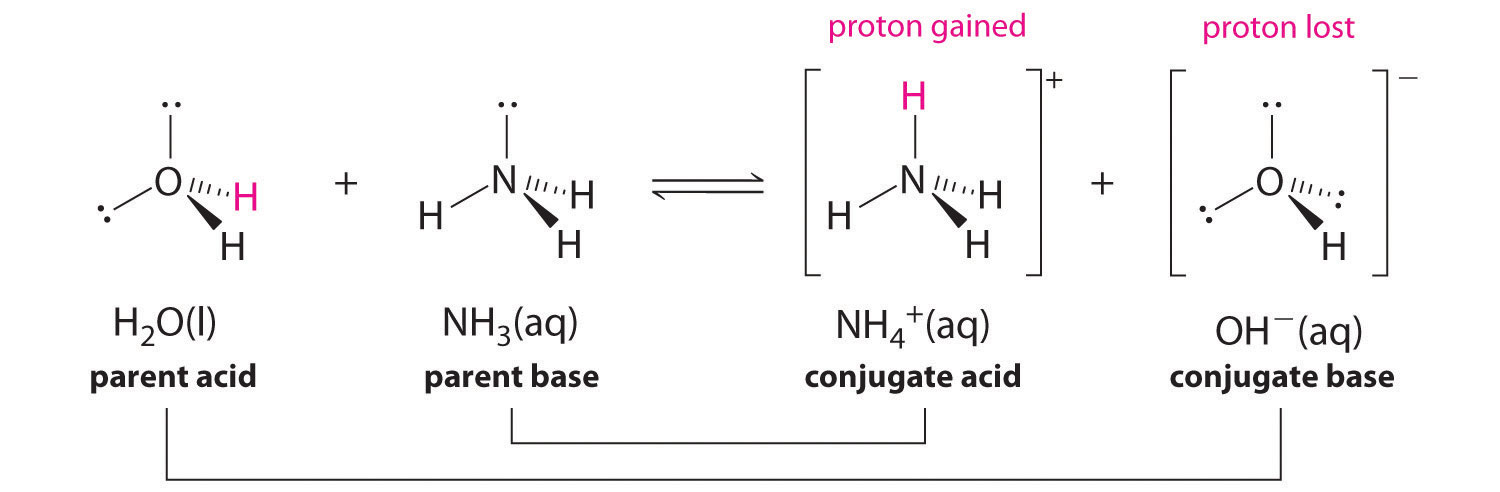

In reality, all acid-base reactions involve the transfer of protons between acids and bases. For example, consider the acid-base reaction that takes place when ammonia is dissolved in water. A water molecule (functioning as an acid) transfers a proton to an ammonia molecule (functioning as a base), yielding the conjugate base of water, \(\ce{OH^-}\), and the conjugate acid of ammonia, \(\ce{NH4+}\):

In the reaction of ammonia with water to give ammonium ions and hydroxide ions, ammonia acts as a base by accepting a proton from a water molecule, which in this case means that water is acting as an acid. In the reverse reaction, an ammonium ion acts as an acid by donating a proton to a hydroxide ion, and the hydroxide ion acts as a base. The conjugate acid–base pairs for this reaction are \(NH_4^+/NH_3\) and \(H_2O/OH^−\).

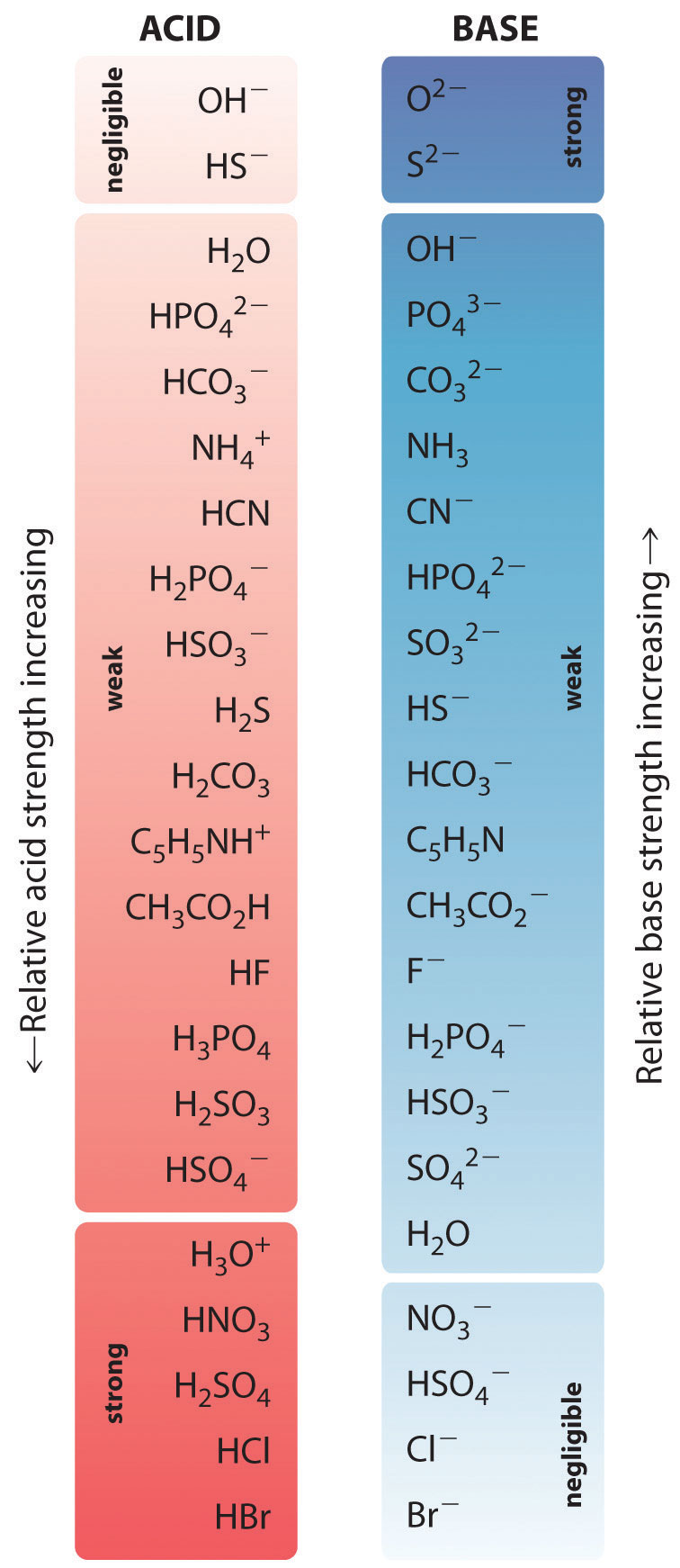

The strongest acids are at the bottom left, and the strongest bases are at the top right. The conjugate base of a strong acid is a very weak base, and, conversely, the conjugate acid of a strong base is a very weak acid.

Identify the conjugate acid-base pairs in this equilibrium.

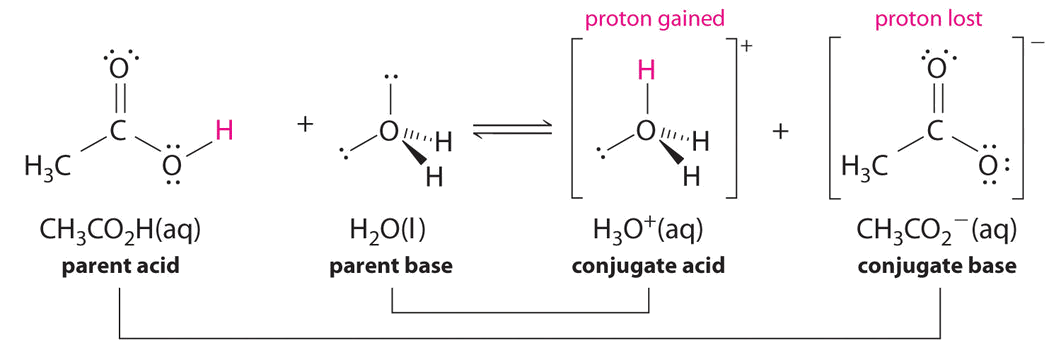

\[\ce{CH3CO2H + H2O \rightleftharpoons H3O^{+} + CH3CO2^{-}} \nonumber \]

Solution

Similarly, in the reaction of acetic acid with water, acetic acid donates a proton to water, which acts as the base. In the reverse reaction, \(H_3O^+\) is the acid that donates a proton to the acetate ion, which acts as the base.

Once again, we have two conjugate acid–base pairs:

- the parent acid and its conjugate base (\(CH_3CO_2H/CH_3CO_2^−\)) and

- the parent base and its conjugate acid (\(H_3O^+/H_2O\)).

Identify the conjugate acid-base pairs in this equilibrium.

\[(CH_{3})_{3}N + H_{2}O\rightleftharpoons (CH_{3})_{3}NH^{+} + OH^{-} \nonumber \]

Solution

One pair is H2O and OH−, where H2O has one more H+ and is the conjugate acid, while OH− has one less H+ and is the conjugate base.

The other pair consists of (CH3)3N and (CH3)3NH+, where (CH3)3NH+ is the conjugate acid (it has an additional proton) and (CH3)3N is the conjugate base.

Identify the conjugate acid-base pairs in this equilibrium.

\[\ce{NH2^{-} + H2O\rightleftharpoons NH3 + OH^{-}} \nonumber \]

- Answer:

- H2O (acid) and OH− (base); NH2− (base) and NH3 (acid)

Buffer Solutions

Weak acids are relatively common, even in the foods we eat. But we occasionally encounter a strong acid or base, such as stomach acid, which has a strongly acidic pH of 1.7. By definition, strong acids and bases can produce a relatively large amount of H+ or OH− ions and consequently have marked chemical activities. In addition, very small amounts of strong acids and bases can change the pH of a solution very quickly. If 1 mL of stomach acid [approximated as 0.1 M HCl(aq)] were added to the bloodstream and no correcting mechanism were present, the pH of the blood would decrease from about 7.4 to about 4.7—a pH that is not conducive to continued living. Fortunately, the body has a mechanism for minimizing such dramatic pH changes.

This mechanism involves a buffer, a solution that resists dramatic changes in pH. Buffers do so by being composed of certain pairs of solutes: either a weak acid plus a salt derived from that weak acid, or a weak base plus a salt of that weak base. For example, a buffer can be composed of dissolved HC2H3O2 (a weak acid) and NaC2H3O2 (the salt derived from that weak acid). Another example of a buffer is a solution containing NH3 (a weak base) and NH4Cl (a salt derived from that weak base).

Let us use an HC2H3O2/NaC2H3O2 buffer to demonstrate how buffers work. If a strong base—a source of OH−(aq) ions—is added to the buffer solution, those OH− ions will react with the HC2H3O2 in an acid-base reaction:

\[\ce{HC2H3O2(aq) + OH^{-}(aq) \rightarrow H2O(ℓ) + C2H3O^{-}2(aq)} \label{Eq1} \]

Rather than changing the pH dramatically by making the solution basic, the added OH− ions react to make H2O, so the pH does not change much.

If a strong acid—a source of H+ ions—is added to the buffer solution, the H+ ions will react with the anion from the salt. Because HC2H3O2 is a weak acid, it is not ionized much. This means that if lots of H+ ions and C2H3O2− ions are present in the same solution, they will come together to make HC2H3O2:

\[\ce{H^{+}(aq) + C2H3O^{−}2(aq) \rightarrow HC2H3O2(aq)} \label{Eq2} \]

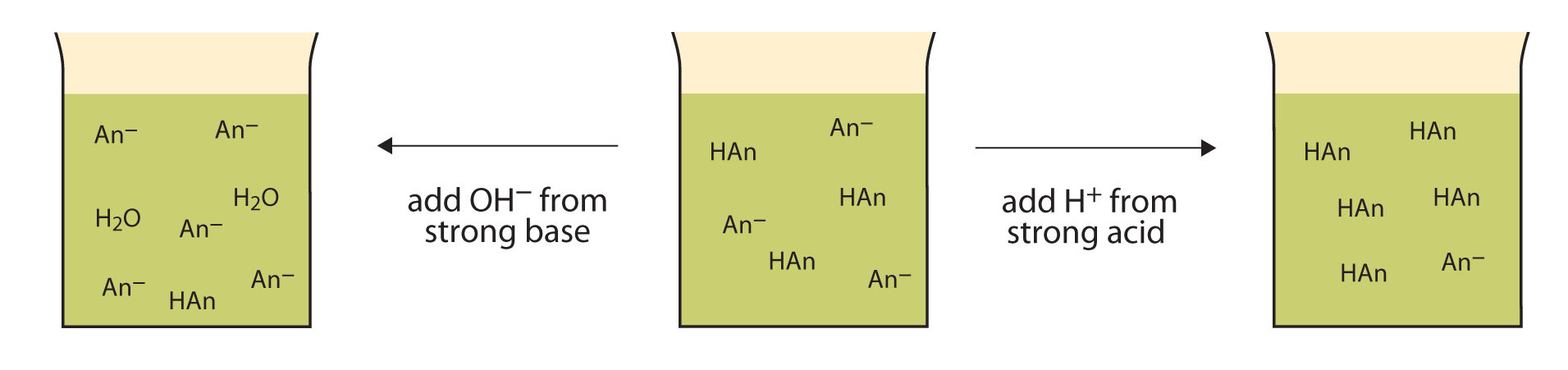

Rather than changing the pH dramatically and making the solution acidic, the added H+ ions react to make molecules of a weak acid. Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) illustrates both actions of a buffer.

Buffers made from weak bases and salts of weak bases act similarly. For example, in a buffer containing NH3 and NH4Cl, NH3 molecules can react with any excess H+ ions introduced by strong acids:

NH3(aq) + H+(aq) → NH4+(aq)

while the NH4+(aq) ion can react with any OH− ions introduced by strong bases:

NH4+(aq) + OH−(aq) → NH3(aq) + H2O(ℓ)

Some common buffer systems are listed in the table below.

| Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) Some Common Buffers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Buffer System | Buffer Components | pH of buffer (equal molarities of both components) |

| Acetic acid/acetate ion | \(\ce{CH_3COOH}\)/\(\ce{CH_3COO^-}\) | 4.74 |

| Carbonic acid/hydrogen carbonate ion | \(\ce{H_2CO_3}\)/\(\ce{HCO_3^-}\) | 6.38 |

| Dihydrogen phosphate ion/hydrogen phosphate ion | \(\ce{H_2PO_4^-}\)/\(\ce{HPO_4^{2-}}\) | 7.21 |

| Ammonia/ammonium ion | \(\ce{NH_3}\)/\(\ce{NH_4^+}\) | 9.25 |

Buffers work well only for limited amounts of added strong acid or base. Once either solute is completely reacted, the solution is no longer a buffer, and rapid changes in pH may occur. We say that a buffer has a certain capacity. Buffers that have more solute dissolved in them to start with have larger capacities, as might be expected.

Human blood has a buffering system to minimize extreme changes in pH. One buffer in blood is based on the presence of HCO3− and H2CO3 [the second compound is another way to write CO2(aq)]. With this buffer present, even if some stomach acid were to find its way directly into the bloodstream, the change in the pH of blood would be minimal. Inside many of the body's cells, there is a buffering system based on phosphate ions.

Which combinations of compounds can make a buffer solution?

- HCHO2 and NaCHO2

- HCl and NaCl

- CH3NH2 and CH3NH3Cl

- NH3 and NaOH

Solution

- HCHO2 is formic acid, a weak acid, while NaCHO2 is the salt made from the anion of the weak acid (the formate ion [CHO2−]). The combination of these two solutes would make a buffer solution.

- HCl is a strong acid, not a weak acid, so the combination of these two solutes would not make a buffer solution.

- CH3NH2 is methylamine, which is like NH3 with one of its H atoms substituted with a CH3 group. Because it is not listed in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), we can assume that it is a weak base. The compound CH3NH3Cl is a salt made from that weak base, so the combination of these two solutes would make a buffer solution.

- NH3 is a weak base, but NaOH is a strong base. The combination of these two solutes would not make a buffer solution.

Which combinations of compounds can make a buffer solution?

- NaHCO3 and NaCl

- H3PO4 and NaH2PO4

- NH3 and (NH4)3PO4

- NaOH and NaCl

- Answer a

- No. While NaHCO3 contains the conjugate base of a weak acid (HCO3- comes from H2CO3), NaCl contains does not contain conjugates from any weak acids or bases.

- Answer b

- Yes. H3PO4 is a weak acid, and NaH2PO4 contains the conjugate base of that weak acid (H2PO4-).

- Answer c

- Yes. NH3 is a weak base, and (NH4)3PO4 contains the conjugate acid of that weak base.

- Answer d

- No. NaOH is a strong base, and NaCl contains does not contain conjugates from any weak acids or bases.

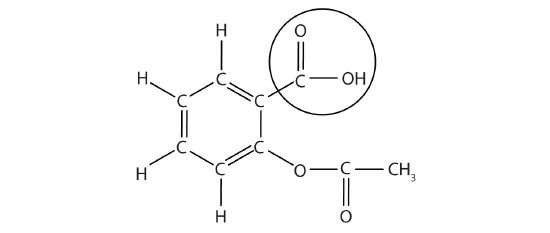

Although medicines are not exactly "food and drink," we do ingest them, so let's take a look at an acid that is probably the most common medicine: acetylsalicylic acid, also known as aspirin. Aspirin is well known as a pain reliever and antipyretic (fever reducer).

The structure of aspirin is shown in the accompanying figure. The acid part is circled; it is the H atom in that part that can be donated as aspirin acts as a Brønsted-Lowry acid. Because it is not given in Table \(\PageIndex{1}\), acetylsalicylic acid is a weak acid. However, it is still an acid, and given that some people consume relatively large amounts of aspirin daily, its acidic nature can cause problems in the stomach lining, despite the stomach's defenses against its own stomach acid.

Because the acid properties of aspirin may be problematic, many aspirin brands offer a "buffered aspirin" form of the medicine. In these cases, the aspirin also contains a buffering agent—usually MgO—that regulates the acidity of the aspirin to minimize its acidic side effects.

As useful and common as aspirin is, it was formally marketed as a drug starting in 1899. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the governmental agency charged with overseeing and approving drugs in the United States, wasn't formed until 1906. Some have argued that if the FDA had been formed before aspirin was introduced, aspirin may never have gotten approval due to its potential for side effects—gastrointestinal bleeding, ringing in the ears, Reye's syndrome (a liver problem), and some allergic reactions. However, recently aspirin has been touted for its effects in lessening heart attacks and strokes, so it is likely that aspirin will remain on the market.

Summary

- A buffer is a solution that resists sudden changes in pH.

- Reactions showing how buffers regulate pH are described.

Contributors and Attributions

- TextMap: Beginning Chemistry (Ball et al.)