7.6: Common elementary steps

- Page ID

- 225801

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Although there there are many different mechanisms, there are just a few common elementary steps that make up those mechanisms. It is useful to examine those in more detail, and to try and recognize each one when it occurs, as this makes it easier to see the similarities between mechanisms.

Acid-base

This is based on the Bronsted-Lowry definition of acid and base, where an H+ is transferred from one atom to another. We have already seen examples of this mechanism in section 6.3. It is perhaps the commonest of all the elementary steps. When talking about elementary steps, we limit the use of this term to those cases where only sigma bonds are broken and made, as here where water acts as a base to remove an H+ from a protonated alcohol:

Often H3O+ (i.e., aqueous acid) serves as the acid, as here:

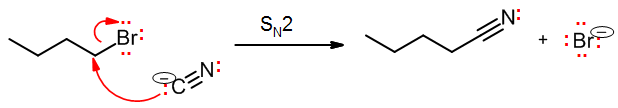

Bimolecular nucleophilic substitution: SN2

We will study the SN2 reaction in depth in the next chapter. Since it is a single-step (concerted) reaction, the reaction is itself an elementary step. The electron flow is a pair of arrows – identical to that of the acid-base, except that the nucleophile is attacking a carbon (or sometimes other elements), not hydrogen.

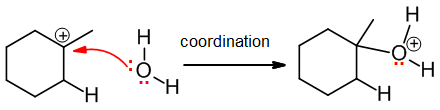

Coordination

Coordination involves the direct bond formation that occurs when a nucleophile attacks an electrophile with an incomplete octet, such as a carbocation:

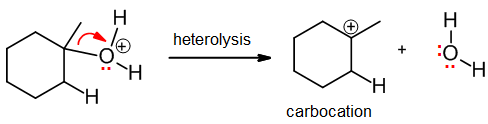

Heterolysis

Heterolysis involves breaking a sigma bond in such a way that both electrons leave with one atom. It is the opposite of coordination, and it results in the formation of a molecule with an incomplete octet, usually a carbocation:

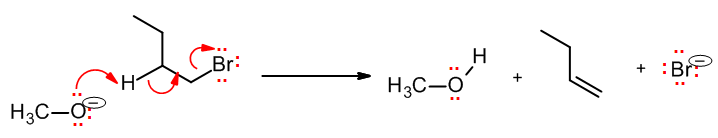

Bimolecular elimination: E2

As with SN2, this is an example of an elementary step that is also the name of the complete one-step reaction; we will study this reaction in depth in section 8.5. Being an elimination, a new pi bond must be formed. The E2 elementary step involves three curved arrows: The base attacks, forms a new pi bond, and the leaving group leaves, all at the same time:

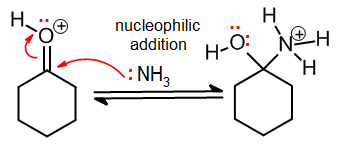

Nucleophilic addition

In nucleophilic addition, a nucleophile attacks a pi bond and breaks it, forming a new sigma bond from the attacking atom. Being an addition, a pi bond must be broken. It is a common elementary step in carbonyl chemistry, where often a C=O (or its protonated form) is attacked by a nucleophile:

Nucleophile elimination

This is the reverse of nucleophilic addition, and thus it results in a nucleophilic group being expelled. In the example given below, the water is the nucleophile being expelled. Being an elimination, a new pi bond must be formed, often a C=O or C=N:

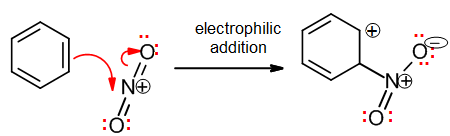

Electrophilic addition

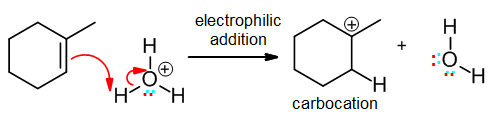

Here, a pi bond attacks an electrophilic atom to form a new sigma bond. Being an addition, a pi bond must be lost:

The electrophile may in fact be H+, in which case the addition may be confused with an acid-base step; note that if a pi bond is lost it should be classified as an electrophilic addition, as here:

Electrophile elimination

This is the reverse of electrophilic addition; in this elementary step an electrophile is ejected and a new pi bond is formed. As with electrophilic addition, the step may be confused with acid-base if the ejected electrophile is based on H+, but if a new pi bond is formed it must be classed as an elimination:

Carbocation rearrangements

These are a more specialized elementary step, but they are mentioned here because we will study these rearrangements in section 8.4. There are two common types, hydride shifts and alkyl shifts, where an H or alkyl respectively migrates towards a C+, and leaves a carbocation on the carbon it left. The example shows a typical hydride shift:

These videos cover the common elementary steps in detail:

References

Joel Karty, “Organic Chemistry: Principles and Mechanism,” Chapter 7, First Edition, Norton.

- Authored by: Martin A. Walker. Provided by: SUNY Potsdam. Located at: http://directory.potsdam.edu/?function=user=walkerma. License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike