5.4: Principles of Oxidation-Reduction Reactions

- Page ID

- 19977

The Learning Objectives of this Module is to identify oxidation–reduction reactions in solution.

The chemical reactions we have described are only a tiny sampling of the infinite number of chemical reactions possible. How do chemists cope with this overwhelming diversity? How do they predict which compounds will react with one another and what products will be formed? The key to success is to find useful ways to categorize reactions. Familiarity with a few basic types of reactions will help you to predict the products that form when certain kinds of compounds or elements come in contact. Most chemical reactions can be classified into one or more of five basic types:

- acid–base reactions,

- exchange reactions,

- condensation reactions

- cleavage reactions,

- and oxidation–reduction reactions.

The general forms of these five kinds of reactions are summarized in Table 3.1, along with examples of each. It is important to note, however, that many reactions can be assigned to more than one classification, as you will see in our discussion. The classification scheme is only for convenience; the same reaction can be classified in different ways, depending on which of its characteristics is most important. Oxidation–reduction reactions, in which there is a net transfer of electrons from one atom to another, and condensation reactions are discussed in this section. Acid–base reactions and one kind of exchange reaction—the formation of an insoluble salt such as barium sulfate when solutions of two soluble salts are mixed together.

Table 3.1 Basic Types of Chemical Reactions

| Name of Reaction | General Form | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| * In more advanced chemisty courses you will learn that this reaction is also called an addition reaction. | ||

| ** In more advanced chemistry courses you will learn that this reaction is also called an elimination reaction. | ||

| oxidation–reduction (redox) | oxidant + reductant → reduced oxidant + oxidized reductant | C7H16(l) + 11O2(g) → 7CO2(g) + 8H2O(g) |

| acid–base | acid + base → salt | NH3(aq) + HNO3(aq) → NH4+(aq) + NO3−(aq) |

| exchange | AB + C → AC + B | CH3Cl + OH− → CH3OH + Cl− |

| AB + CD → AD + CB | BaCl2(aq) + Na2SO4(aq) → BaSO4(s) + 2NaCl(aq) | |

| condensation | A + B → AB | CO2(g) + H2O(l) → H2CO3(aq) |

| HBr + H2C=CH2 → CH3CH2Br* | ||

| cleavage | AB → A + B | CaCO3(s) → CaO(s) + CO2(g) |

| CH3CH2Cl → H2C=CH2 + HCl** | ||

Oxidation–Reduction Reactions

The term oxidation was first used to describe reactions in which metals react with oxygen in air to produce metal oxides. When iron is exposed to air in the presence of water, for example, the iron turns to rust—an iron oxide. When exposed to air, aluminum metal develops a continuous, coherent, transparent layer of aluminum oxide on its surface. In both cases, the metal acquires a positive charge by transferring electrons to the neutral oxygen atoms of an oxygen molecule. As a result, the oxygen atoms acquire a negative charge and form oxide ions (O2−). Because the metals have lost electrons to oxygen, they have been oxidized; oxidation is therefore the loss of electrons. Conversely, because the oxygen atoms have gained electrons, they have been reduced, so reduction is the gain of electrons. For every oxidation, there must be an associated reduction.

| Note |

|---|

| Any oxidation must ALWAYS be accompanied by a reduction and vice versa. |

Originally, the term reduction referred to the decrease in mass observed when a metal oxide was heated with carbon monoxide, a reaction that was widely used to extract metals from their ores. When solid copper(I) oxide is heated with hydrogen, for example, its mass decreases because the formation of pure copper is accompanied by the loss of oxygen atoms as a volatile product (water). The reaction is as follows:

\[ Cu_2O (s) + H_2 (g) \rightarrow 2Cu (s) + H_2O (g) \tag{3.24}\]

Oxidation and reduction reactions are now defined as reactions that exhibit a change in the oxidation states of one or more elements in the reactants, which follows the mnemonic oxidation is loss reduction is gain, or oil rig. The oxidation state of each atom in a compound is the charge an atom would have if all its bonding electrons were transferred to the atom with the greater attraction for electrons. Atoms in their elemental form, such as O2 or H2, are assigned an oxidation state of zero. For example, the reaction of aluminum with oxygen to produce aluminum oxide is

\[ 4 Al (s) + 3O_2 \rightarrow 2Al_2O_3 (s) \tag{3.25} \]

Each neutral oxygen atom gains two electrons and becomes negatively charged, forming an oxide ion; thus, oxygen has an oxidation state of −2 in the product and has been reduced. Each neutral aluminum atom loses three electrons to produce an aluminum ion with an oxidation state of +3 in the product, so aluminum has been oxidized. In the formation of Al2O3, electrons are transferred as follows (the superscript 0 emphasizes the oxidation state of the elements):

\[ 4 Al^0 + 3 O_2^0 \rightarrow 4 Al^{3+} + 6 O^{2-} \tag{3.26}\]

Equation 3.24 and Equation 3.25 are examples of oxidation–reduction (redox) reactions. In redox reactions, there is a net transfer of electrons from one reactant to another. In any redox reaction, the total number of electrons lost must equal the total of electrons gained to preserve electrical neutrality. In Equation 3.26, for example, the total number of electrons lost by aluminum is equal to the total number gained by oxygen:

\[ electrons \, lost = 4 \, Al \, atoms \times {3 \, e^- \, lost \over Al \, atom } = 12 \, e^- \, lost \tag{3.27a}\]

\[ electrons \, gained = 6 \, O \, atoms \times {2 \, e^- \, gained \over O \, atom} = 12 \, e^- \, gained \tag{3.27a}\]

The same pattern is seen in all oxidation–reduction reactions: the number of electrons lost must equal the number of electrons gained.

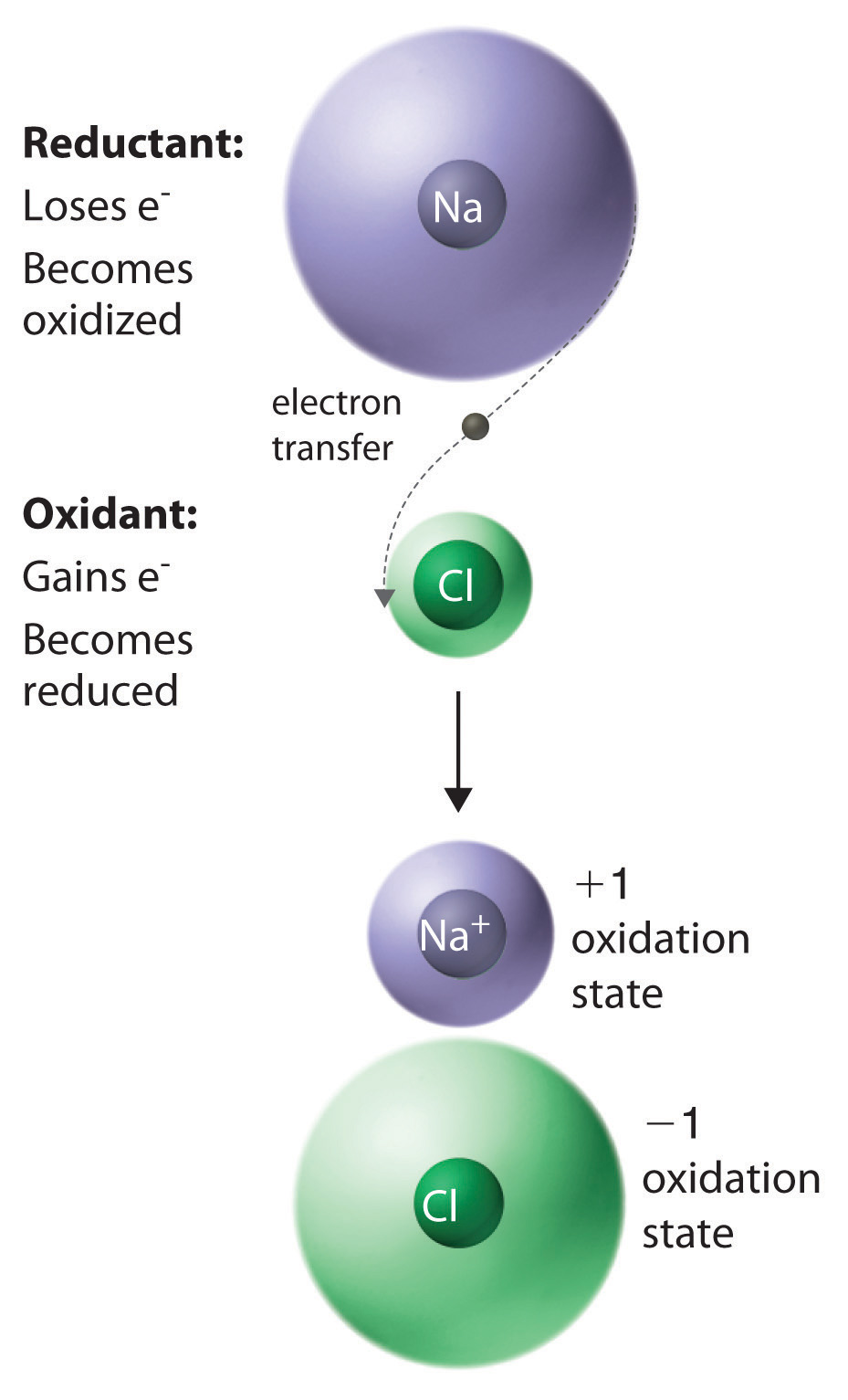

An additional example of a redox reaction, the reaction of sodium metal with oxygen in air, is illustrated in Figure 3.1.

| Note |

|---|

| In all oxidation–reduction (redox) reactions, the number of electrons lost equals the number of electrons gained. |

Assigning Oxidation States

Assigning oxidation states to the elements in binary ionic compounds is straightforward: the oxidation states of the elements are identical to the charges on the monatomic ions. In Chapter 2 "Molecules, Ions, and Chemical Formulas", you learned how to predict the formulas of simple ionic compounds based on the sign and magnitude of the charge on monatomic ions formed by the neutral elements. Examples of such compounds are sodium chloride (NaCl; Figure 3.13), magnesium oxide (MgO), and calcium chloride (CaCl2). In covalent compounds, in contrast, atoms share electrons. Oxidation states in covalent compounds are somewhat arbitrary, but they are useful bookkeeping devices to help you understand and predict many reactions.

Figure 3.13: The Reaction of a Neutral Sodium Atom with a Neutral Chlorine Atom. The result is the transfer of one electron from sodium to chlorine, forming the ionic compound NaCl.

A set of rules for assigning oxidation states to atoms in chemical compounds follows.

Rules for Assigning Oxidation States

- The oxidation state of an atom in any pure element, whether monatomic, diatomic, or polyatomic, is zero.

- The oxidation state of a monatomic ion is the same as its charge—for example, Na+ = +1, Cl− = −1.

- The oxidation state of fluorine in chemical compounds is always −1. Other halogens usually have oxidation states of −1 as well, except when combined with oxygen or other halogens.

- Hydrogen is assigned an oxidation state of +1 in its compounds with nonmetals and −1 in its compounds with metals.

- Oxygen is normally assigned an oxidation state of −2 in compounds, with two exceptions: in compounds that contain oxygen–fluorine or oxygen–oxygen bonds, the oxidation state of oxygen is determined by the oxidation states of the other elements present.

- The sum of the oxidation states of all the atoms in a neutral molecule or ion must equal the charge on the molecule or ion.

Nonintegral oxidation states are encountered occasionally. They are usually due to the presence of two or more atoms of the same element with different oxidation states.

In any chemical reaction, the net charge must be conserved; that is, in a chemical reaction, the total number of electrons is constant, just like the total number of atoms. Consistent with this, rule 1 states that the sum of the individual oxidation states of the atoms in a molecule or ion must equal the net charge on that molecule or ion. In NaCl, for example, Na has an oxidation state of +1 and Cl is −1. The net charge is zero, as it must be for any compound.

Rule 3 is required because fluorine attracts electrons more strongly than any other element, for reasons you will discover in Chapter 6 "The Structure of Atoms". Hence fluorine provides a reference for calculating the oxidation states of other atoms in chemical compounds. Rule 4 reflects the difference in chemistry observed for compounds of hydrogen with nonmetals (such as chlorine) as opposed to compounds of hydrogen with metals (such as sodium). For example, NaH contains the H− ion, whereas HCl forms H+ and Cl− ions when dissolved in water. Rule 5 is necessary because fluorine has a greater attraction for electrons than oxygen does; this rule also prevents violations of rule 2. So the oxidation state of oxygen is +2 in OF2 but −½ in KO2. Note that an oxidation state of −½ for O in KO2 is perfectly acceptable.

The reduction of copper(I) oxide shown in Equation 3.28 demonstrates how to apply these rules. Rule 1 states that atoms in their elemental form have an oxidation state of zero, which applies to H2 and Cu. From rule 4, hydrogen in H2O has an oxidation state of +1, and from rule 5, oxygen in both Cu2O and H2O has an oxidation state of −2. Rule 6 states that the sum of the oxidation states in a molecule or formula unit must equal the net charge on that compound. This means that each Cu atom in Cu2O must have a charge of +1: 2(+1) + (−2) = 0. So the oxidation states are as follows:

\[ \overset {+1}{Cu_2} \underset {-2}{O} (s) + \overset {0}{H_2} (g) \rightarrow 2 \overset {0}{Cu} (s) + \overset {+1}{H_2} \underset {-2}{O} (g) \tag{3.28} \]

Assigning oxidation states allows us to see that there has been a net transfer of electrons from hydrogen (0 → +1) to copper (+1 → 0). So this is a redox reaction. Once again, the number of electrons lost equals the number of electrons gained, and there is a net conservation of charge:

\[ electrons \, lost = 2 \, H \, atoms \times {1 \, e^- \, lost \over H \, atom } = 2 \, e^- \, lost \tag{3.29a}\]

\[ electrons \, gained = 2 \, Cu \, atoms \times {1 \, e^- \, gained \over Cu \, atom} = 2 \, e^- \, gained \tag{3.29b}\]

Remember that oxidation states are useful for visualizing the transfer of electrons in oxidation–reduction reactions, but the oxidation state of an atom and its actual charge are the same only for simple ionic compounds. Oxidation states are a convenient way of assigning electrons to atoms, and they are useful for predicting the types of reactions that substances undergo.

| Example 14 |

|---|

| Assign oxidation states to all atoms in each compound.

Given: molecular or empirical formula Asked for: oxidation states Strategy: Begin with atoms whose oxidation states can be determined unambiguously from the rules presented (such as fluorine, other halogens, oxygen, and monatomic ions). Then determine the oxidation states of other atoms present according to rule 1. Solution: a. We know from rule 3 that fluorine always has an oxidation state of −1 in its compounds. The six fluorine atoms in sulfur hexafluoride give a total negative charge of −6. Because rule 1 requires that the sum of the oxidation states of all atoms be zero in a neutral molecule (here SF6), the oxidation state of sulfur must be +6: [(6 F atoms)(−1)] + [(1 S atom) (+6)] = 0 b. According to rules 4 and 5, hydrogen and oxygen have oxidation states of +1 and −2, respectively. Because methanol has no net charge, carbon must have an oxidation state of −2: [(4 H atoms)(+1)] + [(1 O atom)(−2)] + [(1 C atom)(−2)] = 0 c. Note that (NH4)2SO4 is an ionic compound that consists of both a polyatomic cation (NH4+) and a polyatomic anion (SO42−) (see Table 2.4 "Common Polyatomic Ions and Their Names"). We assign oxidation states to the atoms in each polyatomic ion separately. For NH4+, hydrogen has an oxidation state of +1 (rule 4), so nitrogen must have an oxidation state of −3: [(4 H atoms)(+1)] + [(1 N atom)(−3)] = +1, the charge on the NH4+ ion For SO42−, oxygen has an oxidation state of −2 (rule 5), so sulfur must have an oxidation state of +6: [(4 O atoms) (−2)] + [(1 S atom)(+6)] = −2, the charge on the sulfate ion d. Oxygen has an oxidation state of −2 (rule 5), giving an overall charge of −8 per formula unit. This must be balanced by the positive charge on three iron atoms, giving an oxidation state of +8/3 for iron: Fractional oxidation states are allowed because oxidation states are a somewhat arbitrary way of keeping track of electrons. In fact, Fe3O4 can be viewed as having two Fe3+ ions and one Fe2+ ion per formula unit, giving a net positive charge of +8 per formula unit. Fe3O4 is a magnetic iron ore commonly called magnetite. In ancient times, magnetite was known as lodestone because it could be used to make primitive compasses that pointed toward Polaris (the North Star), which was called the “lodestar.” e. Initially, we assign oxidation states to the components of CH3CO2H in the same way as any other compound. Hydrogen and oxygen have oxidation states of +1 and −2 (rules 4 and 5, respectively), resulting in a total charge for hydrogen and oxygen of [(4 H atoms)(+1)] + [(2 O atoms)(−2)] = 0 So the oxidation state of carbon must also be zero (rule 6). This is, however, an average oxidation state for the two carbon atoms present. Because each carbon atom has a different set of atoms bonded to it, they are likely to have different oxidation states. To determine the oxidation states of the individual carbon atoms, we use the same rules as before but with the additional assumption that bonds between atoms of the same element do not affect the oxidation states of those atoms. The carbon atom of the methyl group (−CH3) is bonded to three hydrogen atoms and one carbon atom. We know from rule 4 that hydrogen has an oxidation state of +1, and we have just said that the carbon–carbon bond can be ignored in calculating the oxidation state of the carbon atom. For the methyl group to be electrically neutral, its carbon atom must have an oxidation state of −3. Similarly, the carbon atom of the carboxylic acid group (−CO2H) is bonded to one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms. Again ignoring the bonded carbon atom, we assign oxidation states of −2 and +1 to the oxygen and hydrogen atoms, respectively, leading to a net charge of [(2 O atoms)(−2)] + [(1 H atom)(+1)] = −3 To obtain an electrically neutral carboxylic acid group, the charge on this carbon must be +3. The oxidation states of the individual atoms in acetic acid are thus \[ \underset {-3}{C} \overset {+1}{H_3} \overset {+3}{C} \underset {-2}{O_2} \overset {+1}{H} \] Thus the sum of the oxidation states of the two carbon atoms is indeed zero. |

| Exercise 14 |

|---|

| Assign oxidation states to all atoms in each compound.

Answer:

|

Redox Reactions of Solid Metals in Aqueous Solution

A widely encountered class of oxidation–reduction reactions is the reaction of aqueous solutions of acids or metal salts with solid metals. An example is the corrosion of metal objects, such as the rusting of an automobile (Figure 8.8.1). Rust is formed from a complex oxidation–reduction reaction involving dilute acid solutions that contain Cl− ions (effectively, dilute HCl), iron metal, and oxygen. When an object rusts, iron metal reacts with HCl(aq) to produce iron(II) chloride and hydrogen gas:

\(Fe(s) + 2HCl(aq) \rightarrow FeCl_2(aq) + H_2(g) \tag{8.8.10}\)

In subsequent steps, FeCl2 undergoes oxidation to form a reddish-brown precipitate of Fe(OH)3.

Figure 8.8.1 Rust Formation. The corrosion process involves an oxidation–reduction reaction in which metallic iron is converted to Fe(OH)3, a reddish-brown solid.

Many metals dissolve through reactions of this type, which have the general form

\(metal + acid \rightarrow salt + hydrogen \tag{8.8.11}\)

Some of these reactions have important consequences. For example, it has been proposed that one factor that contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire was the widespread use of lead in cooking utensils and pipes that carried water. Rainwater, as we have seen, is slightly acidic, and foods such as fruits, wine, and vinegar contain organic acids. In the presence of these acids, lead dissolves:

\( Pb(s) + 2H^+(aq) \rightarrow Pb^{2+}(aq) + H_2(g) \tag{8.8.12}\)

Consequently, it has been speculated that both the water and the food consumed by Romans contained toxic levels of lead, which resulted in widespread lead poisoning and eventual madness. Perhaps this explains why the Roman Emperor Caligula appointed his favorite horse as consul!

Single-Displacement Reactions

Certain metals are oxidized by aqueous acid, whereas others are oxidized by aqueous solutions of various metal salts. Both types of reactions are called single-displacement reactions, in which the ion in solution is displaced through oxidation of the metal. Two examples of single-displacement reactions are the reduction of iron salts by zinc (Equation 8.8.13) and the reduction of silver salts by copper (Equation 8.8.14 and Figure 8.8.2):

\[ Zn(s) + Fe^{2+}(aq) \rightarrow Zn^{2+}(aq) + Fe(s) \tag{8.8.13}\]

\[ Cu(s) + 2Ag^+(aq) \rightarrow Cu^{2+}(aq) + 2Ag(s) \tag{8.8.14}\]

The reaction in Equation 8.8.13 is widely used to prevent (or at least postpone) the corrosion of iron or steel objects, such as nails and sheet metal. The process of “galvanizing” consists of applying a thin coating of zinc to the iron or steel, thus protecting it from oxidation as long as zinc remains on the object.

Figure 8.8.2 The Single-Displacement Reaction of Metallic Copper with a Solution of Silver Nitrate. When a copper coil is placed in a solution of silver nitrate, silver ions are reduced to metallic silver on the copper surface, and some of the copper metal dissolves. Note the formation of a metallic silver precipitate on the copper coil and a blue color in the surrounding solution due to the presence of aqueous Cu2+ ions. Figure used with permission of Wikipedia

Summary

In oxidation–reduction reactions, electrons are transferred from one substance or atom to another. We can balance oxidation–reduction reactions in solution using the oxidation state method (Table 8.8.1), in which the overall reaction is separated into an oxidation equation and a reduction equation.

Key Takeaway

- Oxidation–reduction reactions are balanced by separating the overall chemical equation into an oxidation equation and a reduction equation.

Conceptual Problems

-

Which elements in the periodic table tend to be good oxidants? Which tend to be good reductants?

-

If two compounds are mixed, one containing an element that is a poor oxidant and one with an element that is a poor reductant, do you expect a redox reaction to occur? Explain your answer. What do you predict if one is a strong oxidant and the other is a weak reductant? Why?

-

In each redox reaction, determine which species is oxidized and which is reduced:

- Zn(s) + H2SO4(aq) → ZnSO4(aq) + H2(g)

- Cu(s) + 4HNO3(aq) → Cu(NO3)2(aq) + 2NO2(g) + 2H2O(l)

- BrO3−(aq) + 2MnO2(s) + H2O(l) → Br−(aq) + 2MnO4−(aq) + 2H+(aq)

-

Single-displacement reactions are a subset of redox reactions. In this subset, what is oxidized and what is reduced? Give an example of a redox reaction that is not a single-displacement reaction.

Numerical Problems

-

Balance each redox reaction under the conditions indicated.

- CuS(s) + NO3−(aq) → Cu2+(aq) + SO42−(aq) + NO(g); acidic solution

- Ag(s) + HS−(aq) + CrO42−(aq) → Ag2S(s) + Cr(OH)3(s); basic solution

- Zn(s) + H2O(l) → Zn2+(aq) + H2(g); acidic solution

- O2(g) + Sb(s) → H2O2(aq) + SbO2−(aq); basic solution

- UO22+(aq) + Te(s) → U4+(aq) + TeO42−(aq); acidic solution

-

Balance each redox reaction under the conditions indicated.

- MnO4−(aq) + S2O32−(aq) → Mn2+(aq) + SO42−(aq); acidic solution

- Fe2+(aq) + Cr2O72−(aq) → Fe3+(aq) + Cr3+(aq); acidic solution

- Fe(s) + CrO42−(aq) → Fe2O3(s) + Cr2O3(s); basic solution

- Cl2(aq) → ClO3−(aq) + Cl−(aq); acidic solution

- CO32−(aq) + N2H4(aq) → CO(g) + N2(g); basic solution

-

Using the activity series, predict what happens in each situation. If a reaction occurs, write the net ionic equation; then write the complete ionic equation for the reaction.

- Platinum wire is dipped in hydrochloric acid.

- Manganese metal is added to a solution of iron(II) chloride.

- Tin is heated with steam.

- Hydrogen gas is bubbled through a solution of lead(II) nitrate.

-

Using the activity series, predict what happens in each situation. If a reaction occurs, write the net ionic equation; then write the complete ionic equation for the reaction.

- A few drops of NiBr2 are dropped onto a piece of iron.

- A strip of zinc is placed into a solution of HCl.

- Copper is dipped into a solution of ZnCl2.

- A solution of silver nitrate is dropped onto an aluminum plate.

-

Dentists occasionally use metallic mixtures called amalgams for fillings. If an amalgam contains zinc, however, water can contaminate the amalgam as it is being manipulated, producing hydrogen gas under basic conditions. As the filling hardens, the gas can be released, causing pain and cracking the tooth. Write a balanced chemical equation for this reaction.

-

Copper metal readily dissolves in dilute aqueous nitric acid to form blue Cu2+(aq) and nitric oxide gas.

- What has been oxidized? What has been reduced?

- Balance the chemical equation.

-

Classify each reaction as an acid–base reaction, a precipitation reaction, or a redox reaction, or state if there is no reaction; then complete and balance the chemical equation:

- Pt2+(aq) + Ag(s) →

- HCN(aq) + NaOH(aq) →

- Fe(NO3)3(aq) + NaOH(aq) →

- CH4(g) + O2(g) →

-

Classify each reaction as an acid–base reaction, a precipitation reaction, or a redox reaction, or state if there is no reaction; then complete and balance the chemical equation:

- Zn(s) + HCl(aq) →

- HNO3(aq) + AlCl3(aq) →

- K2CrO4(aq) + Ba(NO3)2(aq) →

- Zn(s) + Ni2+(aq) → Zn2+(aq) + Ni(s)

Contributors

- Anonymous