5.8: de Broglie Wave Equation

- Page ID

- 52966

Bohr's model of the atom was valuable in demonstrating how electrons were capable of absorbing and releasing energy, and how atomic emission spectra were created. However, the model did not really explain why electrons should exist only in fixed circular orbits, rather than being able to exist in a limitless number of orbits with different energies. In order to explain why atomic energy states are quantized, scientists had to rethink their views of the nature of the electron and its movement.

de Broglie Wave Equation

Planck's investigation of the emission spectra of hot objects and the subsequent studies into the photoelectric effect had proven that light was capable of behaving both as a wave and as a particle. It seemed reasonable to wonder if electrons could also have a dual wave-particle nature. In 1924, French scientist Louis de Broglie (1892-1987) derived an equation that described the wave nature of any particle. Particularly, the wavelength \(\left( \lambda \right)\) of any moving object is given by:

\[\lambda = \frac{h}{mv}\nonumber \]

In this equation, \(h\) is Planck's constant, \(m\) is the mass of the particle in \(\text{kg}\), and \(v\) is the velocity of the particle in \(\text{m/s}\). The problem below shows how to calculate the wavelength of the electron.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

An electron of mass \(9.11 \times 10^{-31} \: \text{kg}\) moves at nearly the speed of light. Using a velocity of \(3.00 \times 10^8 \: \text{m/s}\), calculate the wavelength of the electron.

Solution

Step 1: List the known quantities and plan the problem.

Known

- Mass \(\left( m \right) = 9.11 \times 10^{-31} \: \text{kg}\)

- Planck's constant \(\left( h \right) = 6.626 \times 10^{-34} \: \text{J} \cdot \text{s}\)

- Velocity \(\left( v \right) = 3.00 \times 10^8 \: \text{m/s}\)

Unknown

- Wavelength (\(\lambda\))

Apply the de Broglie wave equation \(\lambda = \frac{h}{mv}\) to solve for the wavelength of the moving electron.

Step 2: Calculate.

\[\lambda = \frac{h}{mv} = \frac{6.626 \times 10^{-34} \: \text{J} \cdot \text{s}}{\left( 9.11 \times 10^{-31} \: \text{kg} \right) \times \left( 3.00 \times 10^8 \: \text{m/s} \right)} = 2.42 \times 10^{-12} \: \text{m}\nonumber \]

Step 3: Think about your result.

This very small wavelength is about 1/20 of the diameter of a hydrogen atom. Looking at the equation, as the speed of the electron decreases, its wavelength increases. The wavelengths of everyday large objects with much greater masses should be very small.

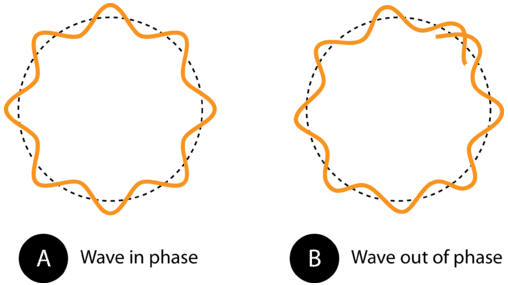

If we were to calculate the wavelength of a \(0.145 \: \text{kg}\) baseball thrown at a speed of \(40 \: \text{m/s}\), we would come up with an extremely short wavelength on the order of \(10^{-34} \: \text{m}\). This wavelength is impossible to detect even with advanced scientific equipment. Indeed, while all objects move with wavelike motion, we never notice it because the wavelengths are far too short. On the other hand, particles with measurable wavelengths are all very small. However, the wave nature of the electron proved to be a key development in a new understanding of the nature of the electron. An electron that is confined to a particular space around the nucleus of an atom can only move around that atom in such a way that its electron wave "fits" the size of the atom correctly. This means that the frequencies of electron waves are quantized. Based on the \(E = h \nu\) equation, the quantized frequencies mean that electrons can only exist in an atom at specific energies, as Bohr had previously theorized.

Summary

- The de Broglie wave equation allows the calculation of the wavelength of any moving object.

- As the speed of the electron decreases, its wavelength increases.

Review

- What did the Bohr model not explain?

- State the de Broglie wave equation.

- What happens as the speed of the electron decreases?