9.3: Molecular Shape and Molecular Polarity

- Page ID

- 91211

Learning Objectives

- To calculate the percent ionic character of a covalent polar bond

Previously, we described the two idealized extremes of chemical bonding:

- ionic bonding—in which one or more electrons are transferred completely from one atom to another, and the resulting ions are held together by purely electrostatic forces—and

- covalent bonding, in which electrons are shared equally between two atoms.

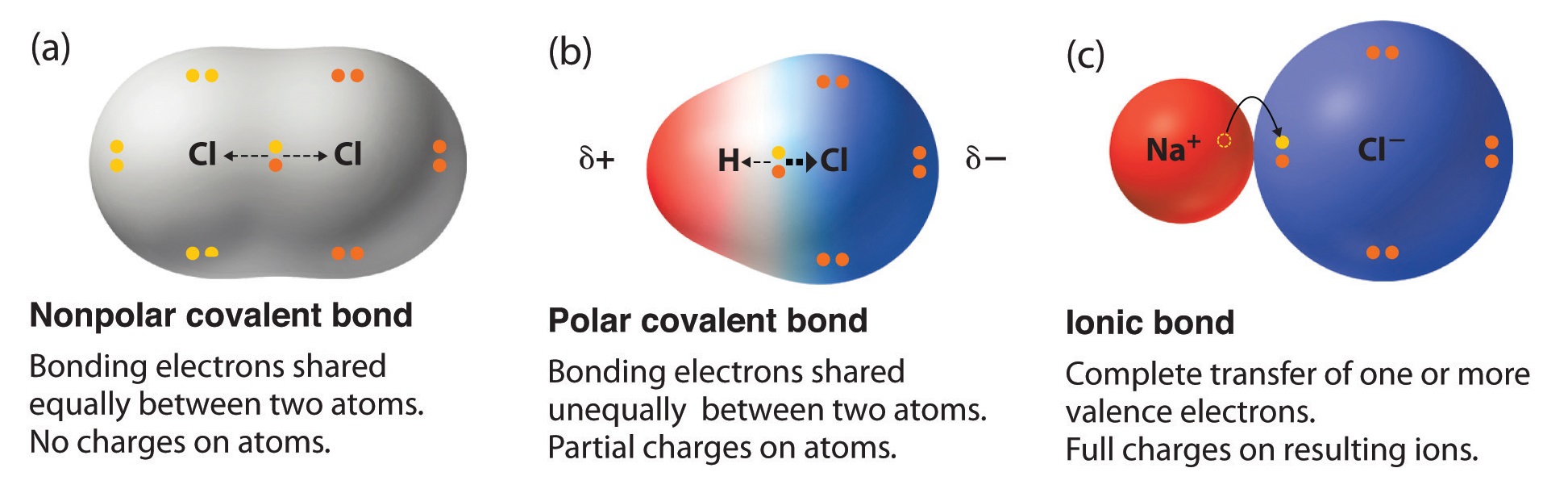

Most compounds, however, have polar covalent bonds, which means that electrons are shared unequally between the bonded atoms. Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\) compares the electron distribution in a polar covalent bond with those in an ideally covalent and an ideally ionic bond. Recall that a lowercase Greek delta (\(\delta\)) is used to indicate that a bonded atom possesses a partial positive charge, indicated by \(\delta^+\), or a partial negative charge, indicated by \(\delta^-\), and a bond between two atoms that possess partial charges is a polar bond.

Bond Polarity

The polarity of a bond—the extent to which it is polar—is determined largely by the relative electronegativities of the bonded atoms. Electronegativity (χ) was defined as the ability of an atom in a molecule or an ion to attract electrons to itself. Thus there is a direct correlation between electronegativity and bond polarity. A bond is nonpolar if the bonded atoms have equal electronegativities. If the electronegativities of the bonded atoms are not equal, however, the bond is polarized toward the more electronegative atom. A bond in which the electronegativity of B (χB) is greater than the electronegativity of A (χA), for example, is indicated with the partial negative charge on the more electronegative atom:

\[ \begin{matrix}

_{less\; electronegative}& & _{more\; electronegative}\\

A\; &-& B\; \; \\

^{\delta ^{+}} & & ^{\delta ^{-}}

\end{matrix} \label{9.3.1} \]

One way of estimating the ionic character of a bond—that is, the magnitude of the charge separation in a polar covalent bond—is to calculate the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms: Δχ = χB − χA.

To predict the polarity of the bonds in Cl2, HCl, and NaCl, for example, we look at the electronegativities of the relevant atoms: χCl = 3.16, χH = 2.20, and χNa = 0.93 (Table A2). Cl2 must be nonpolar because the electronegativity difference (Δχ) is zero; hence the two chlorine atoms share the bonding electrons equally. In NaCl, Δχ is 2.23. This high value is typical of an ionic compound (Δχ ≥ ≈1.5) and means that the valence electron of sodium has been completely transferred to chlorine to form Na+ and Cl− ions. In HCl, however, Δχ is only 0.96. The bonding electrons are more strongly attracted to the more electronegative chlorine atom, and so the charge distribution is

\[ \begin{matrix}

_{\delta ^{+}}& & _{\delta ^{-}}\\

H\; \; &-& Cl

\end{matrix} \]

Remember that electronegativities are difficult to measure precisely and different definitions produce slightly different numbers. In practice, the polarity of a bond is usually estimated rather than calculated.

Bond polarity and ionic character increase with an increasing difference in electronegativity.

As with bond energies, the electronegativity of an atom depends to some extent on its chemical environment. It is therefore unlikely that the reported electronegativities of a chlorine atom in NaCl, Cl2, ClF5, and HClO4 would be exactly the same.

Dipole Moments

The asymmetrical charge distribution in a polar substance such as HCl produces a dipole moment where \( Qr \) in meters (m). is abbreviated by the Greek letter mu (µ). The dipole moment is defined as the product of the partial charge Q on the bonded atoms and the distance r between the partial charges:

\[ \mu=Qr \label{9.3.2} \]

where Q is measured in coulombs (C) and r in meters. The unit for dipole moments is the debye (D):

\[ 1\; D = 3.3356\times 10^{-30}\; C\cdot •m \label{9.7.3} \]

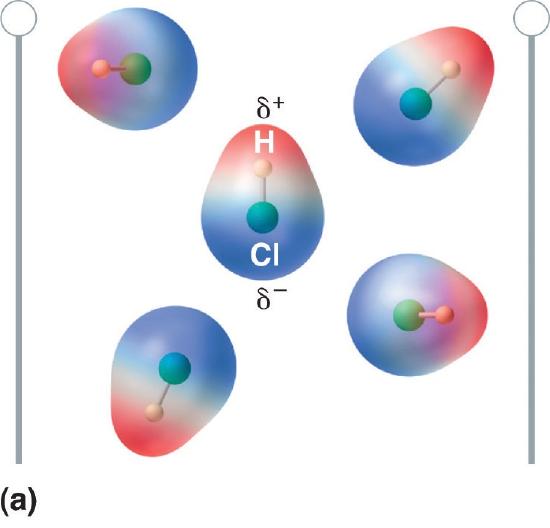

When a molecule with a dipole moment is placed in an electric field, it tends to orient itself with the electric field because of its asymmetrical charge distribution (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

We can measure the partial charges on the atoms in a molecule such as HCl using Equation \(\ref{9.3.2}\). If the bonding in HCl were purely ionic, an electron would be transferred from H to Cl, so there would be a full +1 charge on the H atom and a full −1 charge on the Cl atom. The dipole moment of HCl is 1.109 D, as determined by measuring the extent of its alignment in an electric field, and the reported gas-phase H–Cl distance is 127.5 pm. Hence the charge on each atom is

\[ Q=\dfrac{\mu }{r} =1.109\;\cancel{D}\left ( \dfrac{3.3356\times 10^{-30}\; C\cdot \cancel{m}}{1\; \cancel{D}} \right )\left ( \dfrac{1}{127.8\; \cancel{pm}} \right )\left ( \dfrac{1\; \cancel{pm}}{10^{-12\;} \cancel{m}} \right )=2.901\times 10^{-20}\;C \label{9.7.4} \]

By dividing this calculated value by the charge on a single electron (1.6022 × 10−19 C), we find that the electron distribution in HCl is asymmetric and that effectively it appears that there is a net negative charge on the Cl of about −0.18, effectively corresponding to about 0.18 e−. This certainly does not mean that there is a fraction of an electron on the Cl atom, but that the distribution of electron probability favors the Cl atom side of the molecule by about this amount.

\[ \dfrac{2.901\times 10^{-20}\; \cancel{C}}{1.6022\times 10^{-19}\; \cancel{C}}=0.1811\;e^{-} \label{9.7.5} \]

To form a neutral compound, the charge on the H atom must be equal but opposite. Thus the measured dipole moment of HCl indicates that the H–Cl bond has approximately 18% ionic character (0.1811 × 100), or 82% covalent character. Instead of writing HCl as

\( \begin{matrix}

_{\delta ^{+}}& & _{\delta ^{-}}\\

H\; \; &-& Cl

\end{matrix} \)

we can therefore indicate the charge separation quantitatively as

\( \begin{matrix}

_{0.18\delta ^{+}}& & _{0.18\delta ^{-}}\\

H\; \; &-& Cl

\end{matrix} \)

Our calculated results are in agreement with the electronegativity difference between hydrogen and chlorine χH = 2.20; χCl = 3.16, χCl − χH = 0.96), a value well within the range for polar covalent bonds. We indicate the dipole moment by writing an arrow above the molecule.Mathematically, dipole moments are vectors, and they possess both a magnitude and a direction. The dipole moment of a molecule is the vector sum of the dipoles of the individual bonds. In HCl, for example, the dipole moment is indicated as follows:

![]()

The arrow shows the direction of electron flow by pointing toward the more electronegative atom.

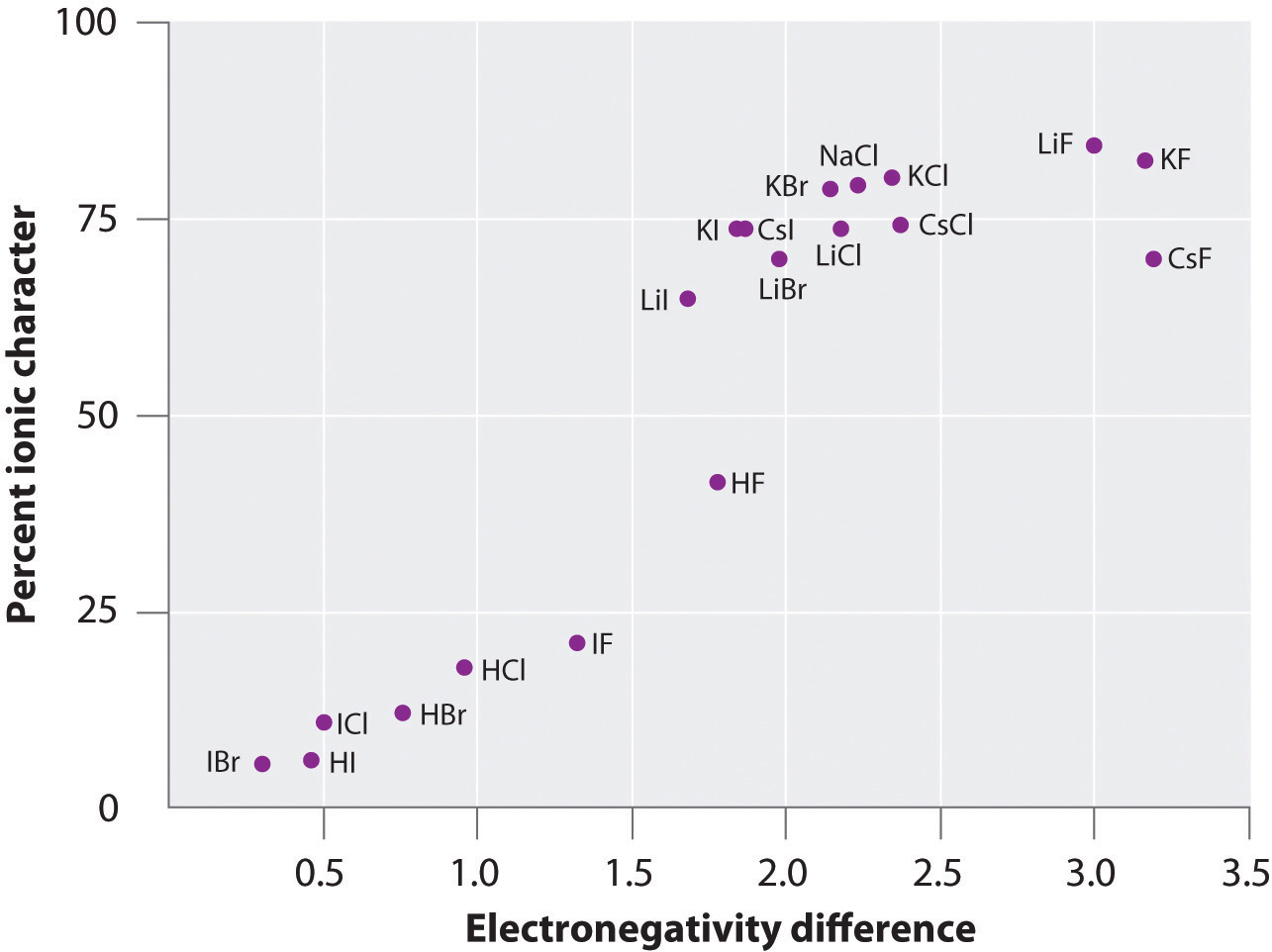

The charge on the atoms of many substances in the gas phase can be calculated using measured dipole moments and bond distances. Figure 9.3.3 shows a plot of the percent ionic character versus the difference in electronegativity of the bonded atoms for several substances. According to the graph, the bonding in species such as \(NaCl_{(g)}\) and \(CsF_{(g)}\) is substantially less than 100% ionic in character. As the gas condenses into a solid, however, dipole–dipole interactions between polarized species increase the charge separations. In the crystal, therefore, an electron is transferred from the metal to the nonmetal, and these substances behave like classic ionic compounds. The data in Figure 9.3.3 show that diatomic species with an electronegativity difference of less than 1.5 are less than 50% ionic in character, which is consistent with our earlier description of these species as containing polar covalent bonds. The use of dipole moments to determine the ionic character of a polar bond is illustrated in Example \(\PageIndex{1}\).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

In the gas phase, NaCl has a dipole moment of 9.001 D and an Na–Cl distance of 236.1 pm. Calculate the percent ionic character in NaCl.

Given: chemical species, dipole moment, and internuclear distance

Asked for: percent ionic character

Strategy:

- Compute the charge on each atom using the information given and Equation \(\ref{9.3.2}\)

- Find the percent ionic character from the ratio of the actual charge to the charge of a single electron.

Solution:

A The charge on each atom is given by

\[ Q=\dfrac{\mu }{r} =9.001\;\cancel{D}\left ( \dfrac{3.3356\times 10^{-30}\; C\cdot \cancel{m}}{1\; \cancel{D}} \right )\left ( \dfrac{1}{236.1\; \cancel{pm}} \right )\left ( \dfrac{1\; \cancel{pm}}{10^{-12\;} \cancel{m}} \right )=1.272\times 10^{-19}\;C \]

Thus NaCl behaves as if it had charges of 1.272 × 10−19 C on each atom separated by 236.1 pm.

B The percent ionic character is given by the ratio of the actual charge to the charge of a single electron (the charge expected for the complete transfer of one electron):

\[ \% \; ionic\; character=\left ( \dfrac{1.272\times 10^{-19}\; \cancel{C}}{1.6022\times 10^{-19}\; \cancel{C}} \right )\left ( 100 \right )=79.39\%\simeq 79\% \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

In the gas phase, silver chloride (AgCl) has a dipole moment of 6.08 D and an Ag–Cl distance of 228.1 pm. What is the percent ionic character in silver chloride?

Answer: 55.5%

Summary

Bond polarity and ionic character increase with an increasing difference in electronegativity.

\[ \mu = Qr \nonumber\]

Compounds with polar covalent bonds have electrons that are shared unequally between the bonded atoms. The polarity of such a bond is determined largely by the relative electronegativites of the bonded atoms. The asymmetrical charge distribution in a polar substance produces a dipole moment, which is the product of the partial charges on the bonded atoms and the distance between them.

Contributors and Attributions

Modified by Joshua Halpern (Howard University)