2.1: The Structure of Proteins

- Page ID

- 165266

Drawing the amino acids

In chemistry, if you were to draw the structure of a general 2-amino acid, you would probably draw it like this:

![]()

However, for drawing the structures of proteins, we usually twist it so that the "R" group sticks out at the side. It is much easier to see what is happening if you do that.

![]()

That means that the two simplest amino acids, glycine and alanine, would be shown as:

Peptides and polypeptides

Glycine and alanine can combine together with the elimination of a molecule of water to produce a dipeptide. It is possible for this to happen in one of two different ways - so you might get two different dipeptides.

Either:

Or:

In each case, the linkage shown in blue in the structure of the dipeptide is known as a peptide link. In chemistry, this would also be known as an amide link, but since we are now in the realms of biochemistry and biology, we'll use their terms.

If you joined three amino acids together, you would get a tripeptide. If you joined lots and lots together (as in a protein chain), you get a polypeptide.

A protein chain will have somewhere in the range of 50 to 2000 amino acid residues. You have to use this term because strictly speaking a peptide chain isn't made up of amino acids. When the amino acids combine together, a water molecule is lost. The peptide chain is made up from what is left after the water is lost - in other words, is made up of amino acid residues.

By convention, when you are drawing peptide chains, the -NH2 group which hasn't been converted into a peptide link is written at the left-hand end. The unchanged -COOH group is written at the right-hand end.

The end of the peptide chain with the -NH2 group is known as the N-terminal, and the end with the -COOH group is the C-terminal.

A protein chain (with the N-terminal on the left) will therefore look like this:

The "R" groups come from the 20 amino acids which occur in proteins. The peptide chain is known as the backbone, and the "R" groups are known as side chains.

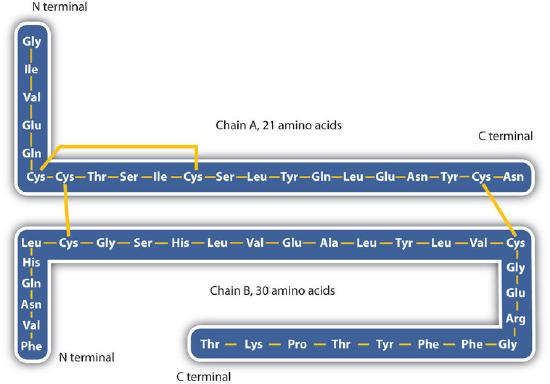

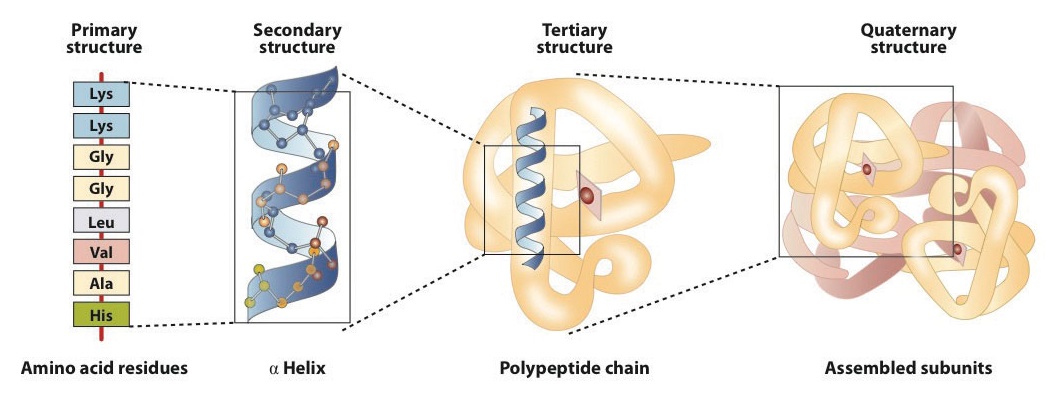

The primary structure of proteins

The structure of proteins is generally described as having four organizational levels. The first of these is the primary structure, which is the number and sequence of amino acids in a protein’s polypeptide chain or chains, beginning with the free amino group and maintained by the peptide bonds connecting each amino acid to the next. The primary structure of insulin, composed of 51 amino acids, is shown in Figure 2.1.1.

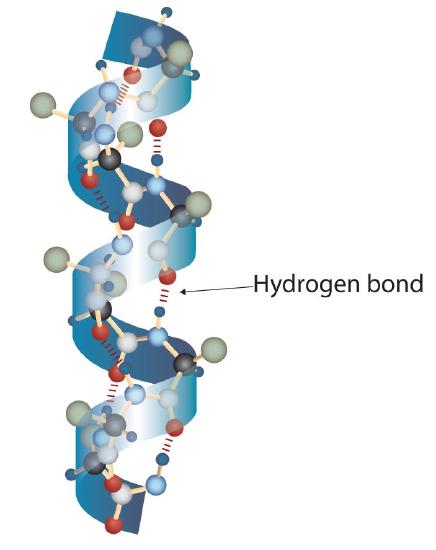

The secondary structure of proteins

A protein molecule is not a random tangle of polypeptide chains. Instead, the chains are arranged in unique but specific conformations. The term secondary structure refers to the fixed arrangement of the polypeptide backbone. On the basis of X ray studies, Linus Pauling and Robert Corey postulated that certain proteins or portions of proteins twist into a spiral or a helix. This helix is stabilized by intrachain hydrogen bonding between the carbonyl oxygen atom of one amino acid and the amide hydrogen atom four amino acids up the chain (located on the next turn of the helix) and is known as a right-handed α-helix. X ray data indicate that this helix makes one turn for every 3.6 amino acids, and the side chains of these amino acids project outward from the coiled backbone (Figure 2.1.2). The α-keratins, found in hair and wool, are exclusively α-helical in conformation. Some proteins, such as gamma globulin, chymotrypsin, and cytochrome c, have little or no helical structure. Others, such as hemoglobin and myoglobin, are helical in certain regions but not in others.

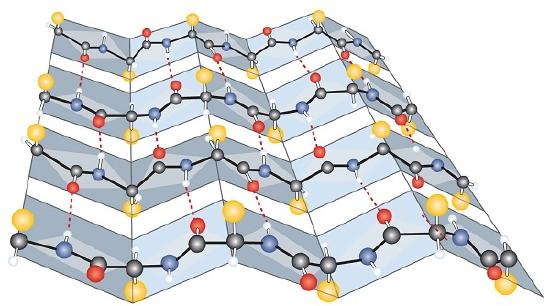

Another common type of secondary structure, called the β-pleated sheet conformation, is a sheetlike arrangement in which two or more extended polypeptide chains (or separate regions on the same chain) are aligned side by side. The aligned segments can run either parallel or antiparallel—that is, the N-terminals can face in the same direction on adjacent chains or in different directions—and are connected by interchain hydrogen bonding (Figure 2.1.3). The β-pleated sheet is particularly important in structural proteins, such as silk fibroin. It is also seen in portions of many enzymes, such as carboxypeptidase A and lysozyme.

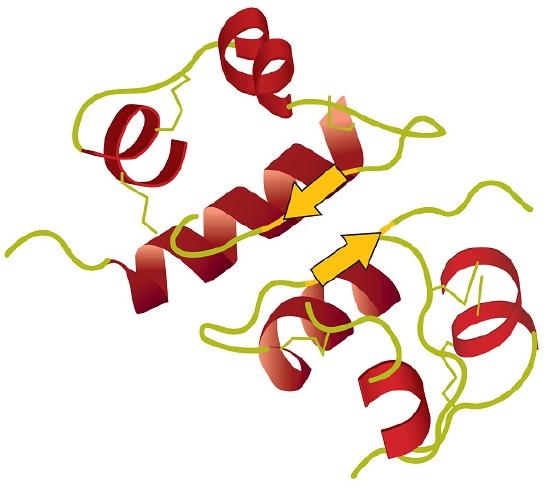

The tertiary structure of proteins

Tertiary structure refers to the unique three-dimensional shape of the protein as a whole, which results from the folding and bending of the protein backbone. The tertiary structure is intimately tied to the proper biochemical functioning of the protein. Figure 2.1.4 shows a depiction of the three-dimensional structure of insulin.

The Quaternary Structure of Protein

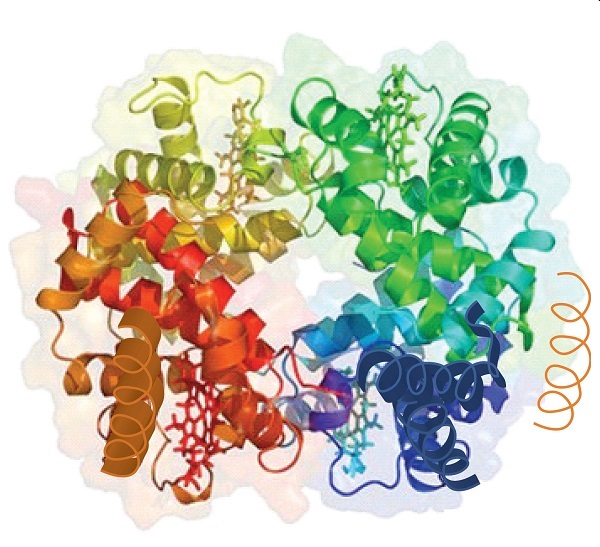

When a protein contains more than one polypeptide chain, each chain is called a subunit. The arrangement of multiple subunits represents a fourth level of structure, the quaternary structure of a protein. Hemoglobin, with four polypeptide chains or subunits, is the most frequently cited example of a protein having quaternary structure (Figure 2.1.5). The quaternary structure of a protein is produced and stabilized by the same kinds of interactions that produce and maintain the tertiary structure.

Source: Image from the RCSB PDB (www.pdb.org) of PDB ID 1I3D (R.D. Kidd, H.M. Baker, A.J. Mathews, T. Brittain, E.N. Baker (2001) Oligomerization and ligand binding in a homotetrameric hemoglobin: two high-resolution crystal structures of hemoglobin Bart's (gamma(4)), a marker for alpha-thalassemia. Protein Sci. 1739–1749).

The primary structure consists of the specific amino acid sequence. The resulting peptide chain can twist into an α-helix, which is one type of secondary structure. This helical segment is incorporated into the tertiary structure of the folded polypeptide chain. The single polypeptide chain is a subunit that constitutes the quaternary structure of a protein, such as hemoglobin that has four polypeptide chains.

What holds a protein into its tertiary structure?

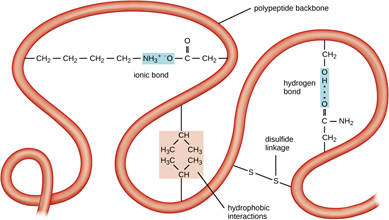

The tertiary structure of a protein is held together by interactions between the side chains - the "R" groups. There are several ways this can happen.

Ionic interactions

Some amino acids (such as aspartic acid and glutamic acid) contain an extra -COOH group. Some amino acids (such as lysine) contain an extra -NH2 group.

You can get a transfer of a hydrogen ion from the -COOH to the -NH2 group to form zwitterions just as in simple amino acids.

You could obviously get an ionic bond between the negative and the positive group if the chains folded in such a way that they were close to each other.

Hydrogen bonds

Notice that we are now talking about hydrogen bonds between side groups - not between groups actually in the backbone of the chain.

Lots of amino acids contain groups in the side chains which have a hydrogen atom attached to either an oxygen or a nitrogen atom. This is a classic situation where hydrogen bonding can occur.

For example, the amino acid serine contains an -OH group in the side chain. You could have a hydrogen bond set up between two serine residues in different parts of a folded chain.

You could easily imagine similar hydrogen bonding involving -OH groups, or -COOH groups, or -CONH2 groups, or -NH2 groups in various combinations - although you would have to be careful to remember that a -COOH group and an -NH2 group would form a zwitterion and produce stronger ionic bonding instead of hydrogen bonds.

Hydrophobic interactions

This is considered a major driving force for protein folding. The hydrophobic amino acids, especially the hydrophobic R groups, interact with one another to form a "core" and push out water molecules.

van der Waals dispersion forces

Several amino acids have quite large hydrocarbon groups in their side chains. A few examples are shown below. Temporary fluctuating dipoles in one of these groups could induce opposite dipoles in another group on a nearby folded chain.

The dispersion forces set up would be enough to hold the folded structure together.

Sulfur bridges

Sulfur bridges which form between two cysteine residues have already been discussed under primary structures. Wherever you choose to place them doesn't affect how they are formed!